by Eric Barton | October 17, 2023

The Rebirth of Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey From Cannon Blasts to Crisscrossing Heights

The reopening of The Greatest Show on Earth marks the reimagination of a Florida icon and a return of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus after a six-year hiatus.

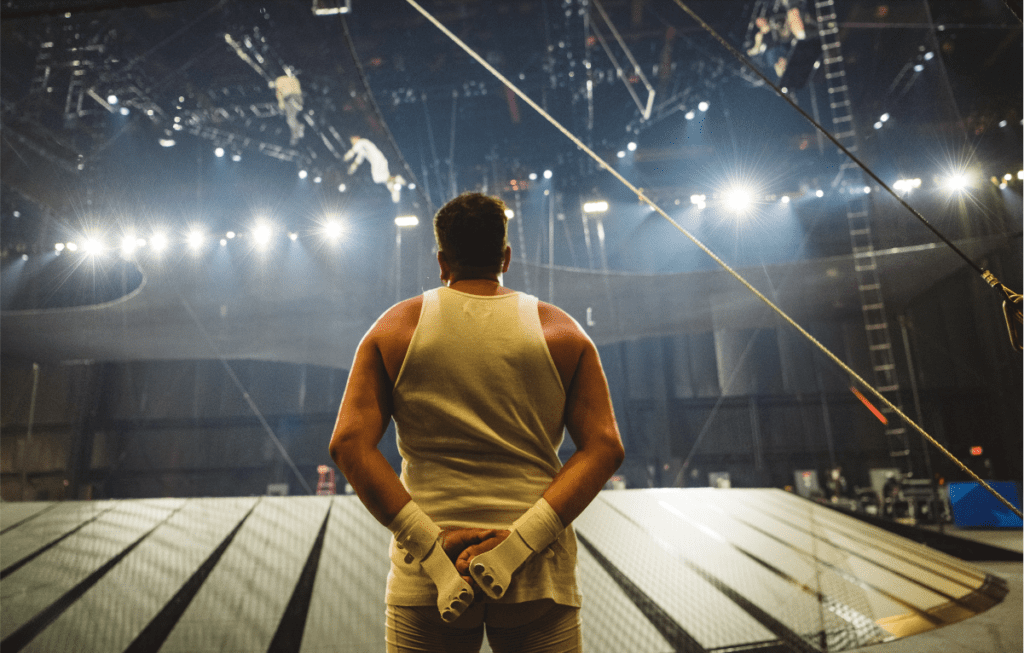

George Caceres does not look like a man about to risk his life. He’s casually shaking out his arms, letting them flail at his side like hooked mackerel. As calm as the Intracoastal on a windless morning, he straightens his white spandex shorts, pulling them down lower on his thighs. Behind him in the massive Tampa Bay rehearsal hall for the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey circus, a crew dressed in all black drags a massive net across the main stage—the net that will later, hopefully, save Caceres from a hard landing.

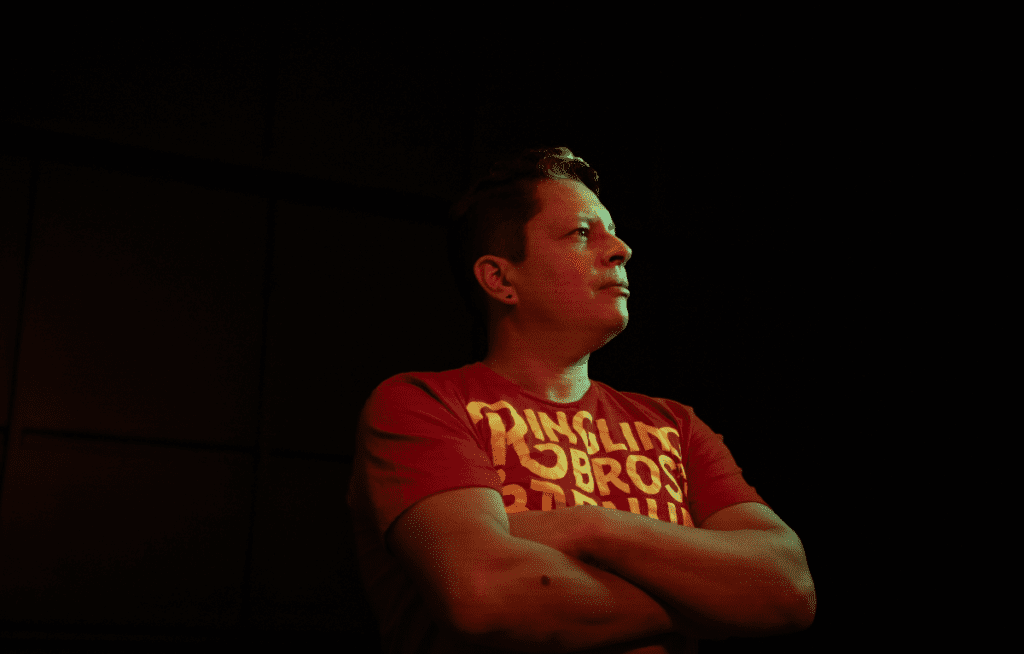

At 45 years old, Caceres is the leader of a trapeze troupe that, aside from him, appears to have an average age of sophomore year in college. These days, he’s more teaching and leading than leaping and catching. A shock of silver runs from the center of his hairline through his black hair, like he’s been scared hard one too many times.

The trapeze troupe has been practicing for 31 days on a new routine that Caceres choreographed. If it works, it will headline the recently reborn Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey. The firm that owns Ringling, Florida-based Feld Entertainment, shuttered the circus in 2017 after a public outcry over elephant performers and a resulting decline in ticket sales. It’s late on a Monday, and they have 45 more rehearsals until opening night on Sept. 29 in Bossier City, Louisiana. I ask Caceres if his troupe is ready, if they’ve done the new stunt he just invented.

“No,” he says quickly. “We realized some things about the act that we couldn’t see on paper.”

The sketched-out version, he explains, involves a troupe of nine performers who take turns swinging from two platforms, narrowly passing each other above the center ring. If he can pull it off, the finale will be spectacular. For now, they’ll keep working on the basics. “Maybe next Wednesday we will try it. Maybe by the end of this week, I don’t know,” Caceres says.

It’s just then that Ringling’s director of casting and performance comes over. Giulio Scatola inserts himself into the troupe’s circle with the confidence of a man very much in charge. If this were a movie or a dramatic TV show, Scatola hit his mark with dramatic timing. “George,” he says, “at about 5:45, I would like to run the whole thing.”

“The whole thing,” Caceres says, not as a question but a statement.

“Yes, the whole thing.”

The whole thing. The entire act, the one the troupe wasn’t ready to attempt, as of one minute ago, will be attempted in less than an hour. Caceres pauses, considering the dangers. They are performers, always ready, the most capable among their profession. They are the trapeze artists of Ringling Bros.

“OK.” Caceres lets a wry smile spread as he heads off to begin stretching.

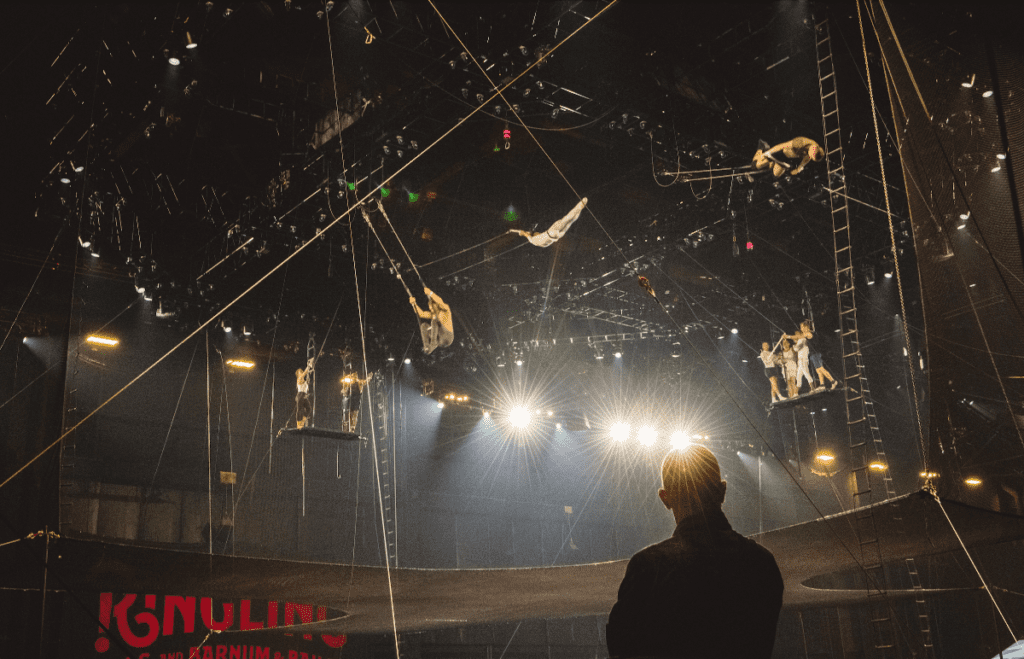

“Going up!” a crew leader shouts from the other side of the ring, and on her command, the net rises all at once. Ringling had it sewn specially for this act, shaped like the equal sided Red Cross symbol, to protect the performers as they make their perilous two-direction route.

The troupe climbs rope ladders up to platforms 31 feet off the ground and begins jumping off, swinging out over the net. On the opposite side, two wide-shouldered performers wait to catch them, hanging upside down from fast-moving swings. The first performers leap off, one by one, pirouetting and spinning and flipping into the arms of the catchers. It seems they have a success rate just over 50%, half the time falling into the net below. It very much looks like Caceres was right—nobody’s ready for the whole thing.

It’s like you don’t really know what could happen to you. You’re innocent. It’s later in life that you become really scared.

—George Caceres

Minutes tick by as they practice. Word spreads that Scatola is stuck in a meeting, and 5:45 comes and goes. Does he still want them to run the whole thing? The performers begin lounging on the net and watching YouTube videos from a single phone.

It’s 6:20 by the time Scatola breezes back in, apologizing. He asks Caceres if the troupe is ready.

“Oh, it’s going to happen,” Caceres says. His team, seven men and two women, climb back up the ladders. Scatola queues the music—a dramatic, drum-heavy song—which sounds like the background of a cinematic car chase.

Scatola grabs a microphone that blasts his words over the sound system. “Ten seconds. Four. Three. Two. One. Let’s do this.”

One by one, the performers begin to fly out, letting go at the apex of their swings, landing in the arms of the catchers. One by one, they nail it, flying back onto their own swings and then back to the two platforms. Not one single drop. All six of them go, and then finally it’s Caceres’s turn. His lone swing out and back will signal the start of the big finale, the thing that has never been tried.

The music crescendos, drums and horns and guitars blare; two hands on the swing, like he’s done a million times before—ever since his first step off a trapeze platform at 4 years old. Caceres leaps.

The return of Ringling is a massive, multimillion-dollar investment by Feld Entertainment. The goal is ambitious: recreate the concept of a circus. It’s a monumental task in an era in which all of us are inundated, all day long, by internet videos of people doing extraordinary things. But Feld bets audiences will still be willing to pay to see those things in person.

There’s more on the line than just the success of Ringling. Feld’s headquarters in Palmetto, on the south side of Tampa Bay, could also bring a return of the circus culture. The Sarasota-Bradenton area sprung up largely after the arrival of Ringling in 1927, and there are hopes that its return will bring circus culture back to the shores of the Gulf Coast.

But first, before any of that can happen, Caceres must stick what comes after that leap off the platform. He swings out, his body extending down below the swing. He lets go, his hands outstretched now, every part of him reaching, stretching, pulling toward the forearms of the performer waiting on the swing. Just inches.

Inside One of Florida’s Largest Buildings

The headquarters of Feld Entertainment rises like a massive spaceship that landed on an unexplored planet, ascending from the sand and scraggly bush of inland Florida with little else around it. For a long time, according to Ringling, it stood as the state’s second largest building, after NASA’s Vehicle Assembly Building—that was until an Amazon fulfillment center recently surpassed it.

There apparently aren’t a lot of visitors to Feld, so there’s nobody manning the front desk when I arrive on a Monday morning. A Feld greeter meets me instead at the door. We head back into a maze of hallways snaking through the 600,000-square-foot building, more than 10 times larger than the White House. Ringling performers are practicing here six days a week now, but this is also home to Feld’s other touring shows, including “Monster Jam,” “Disney On Ice” and “Marvel Universe Live!” Performers for those shows also practice here, and the monster trucks sit in their own bay getting serviced between shows.

In the hallway, we run into Kenneth Feld, the owner, and his daughter, Juliette Feld Grossman. She’s being groomed, along with her two sisters, to someday become the third Feld generation to take charge of the entertainment empire.

“Oh, hey!” Feld Grossman says with a charming smile. The four of us make our way toward Ringling’s practice hall, where the performers have already begun a 10-hour rehearsal broken down into roughly hour-long sections for each act. “There are probably thousands of queues in this production for lighting, sound, rigging, staging elements—all these pieces that have to be expertly choreographed,” Feld Grossman told me earlier by phone.

Those of us who know and have lived it and have spent more than 15 seconds of Twitter time trying to understand it, the performers and their animals were the most important part of their lives. It was a very crushing blow for anyone who knew and who had lived that.

— George Caceres

Out of all the shows Feld owns, this one isn’t just business, she says. Feld Grossman’s grandfather, Irvin Feld, bought Ringling in 1967. One of her earliest memories is putting on a clown outfit and being one of the performers to pour out of a tiny car. She’d spend school breaks at Ringling rehearsals. “Ringling is so close to our heart. It has been part of the Feld family longer than it was part of Ringling or Barnum. We take the responsibility of this iconic property seriously. I grew up around it. It was heartbreaking to close it, but it was also the business decision we had to make.”

Pressure from animal rights groups forced Ringling to remove elephants from the show in 2016 (they were retired to the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Center for Elephant Conservation). Ticket sales never recovered. When Feld finally closed the circus just months after retiring the elephants, ending a 146-year run, there was no promise that it would return.

Bringing it back now, Feld Grossman says the family recognized the challenge from on-demand entertainment available these days in everyone’s pockets. They decided Ringling would need key changes to help it succeed in the era of YouTube. They’d celebrate the performers, while also bringing the audience into the show—like the circus, but with greater engagement.

As we head into Ringling’s 60,000-square-foot rehearsal hall, it’s difficult at first to take in the vastness of it. Partial walls and curtains separate large parts of the space into a green room, stretching areas and separate rehearsal spaces for different acts. Finally, we come to the center of the room and step around a tall platform where the producers have a row of desks, and the three rings are finally in focus. They’re made up of geometric shapes and bright colors, like a life-size Fisher Price circus toy. It’s all built in pieces so it can be broken down and rebuilt, shipped on roughly 25 semi-trucks. Above us, lights in the rafters flood the place, illuminating a group of dancers from South America, a team of trick BMX riders and black-clothed stagehands that seems to be scrambling in every direction.

There are 75 people in the cast, 51 crew members and 12 on the creative staff. It’s a fraction of the thousands that used to travel the country with Ringling. But if this new Ringling Bros. succeeds, the show could bring something long missing back to its home place.

Ringling’s Century in Sarasota

After a 45-minute drive down Tamiami Trail, Jennifer Lemmer Posey meets me in the lobby of the Ringling Museum’s Tibbals Learning Center and leads the way to her second-floor office, where circus memorabilia hangs between cubicles.

When she was a girl, Lemmer Posey’s parents would take her to Ringling on her birthday—the circus coincidentally always passed through Jacksonville in January. She hadn’t been to a show in years before getting an internship at the museum while she was an art history student at nearby New College. That was 21 years ago, and now she’s the Tibbals curator of circus. “Every day,” she says, “there’s something I get to learn about.”

Lemmer Posey explains that the heyday of the circus, the era of “The Greatest Show on Earth,” began thanks to P.T. Barnum in 1871. That’s when he added a second and third ring to his shows. Before then, the circus largely consisted of a series of performers taking a single stage, one act at a time, often new immigrants showing off some skill they brought from the remote corners of the globe. Barnum’s three rings turned it into a spectacle, with multiple acts performing at once, leaving the audience wondering where to turn their attention.

“Once you get more than one ring,” Lemmer Posey says, “one of the joys and frustrations is you don’t know where to look.”

Starting in 1927, Ringling’s cast and crew began wintering in Sarasota. John Ringling and his wife Mable built Ca’ d’Zan (Venetian for House of John), a castle on the shores of Sarasota Bay. Modeled in Moorish style, the tower rises five stories like a lighthouse, which he hoped would guide the way to a new era for his family.

Ringling’s circus performers and animals would make their winter homes off Fruitville Road. They bought houses in Sarasota and built trapeze nets and animal enclosures in their backyards. “The circus community started implanting itself,” Lemmer Posey says. Her children go to school now with their descendants, with the last names of Wallenda, Zacchini and Zerbini.

Traveling to Sarasota? Here’s our four favorite spots.

In the center of St. Armands Circle, the city’s island entertainment district as envisioned by John Ringling, stands the Circus Ring of Fame, with monuments to the performers who called this place home. It’s overseen now by Bill Powell, 71, a former Ringling employee and son of two legendary performers. You might know his mother, the late Gee Gee Engesser, an animal keeper who was the first person to ride atop a team of 16 horses hitched together. Her curly blonde hair and sparkly costume would catch the spotlights as she stood astride the final two horses, one foot on each, like a mythical conqueror.

Powell lived with his grandparents in Sarasota while the circus traveled. But when his parents came home, they brought the animals they kept, including elephants, and Powell remembers sharing his breakfast with them in his backyard—quite literally, feeding them fruit as he ate a bowl of cereal. “I grew up with a menagerie.” His mom had 12 acres in Apollo Beach, and the animals would roam free. He loved the elephants, but his favorites were the Alaskan Malamutes, Arctic and Blizzard first, then later Gigi, Roxy and Shell.

Like many children of performers, his parents pushed him to do something different, and after he attended the University of South Florida, he did PR for a newspaper and a phone company. He ended up at Ringling and worked there for 45 years. He’s still bitter about the animal rights activism that helped kill Ringling, he says, because they didn’t understand how well the animals were kept.

“Those of us who know and have lived it and have spent more than 15 seconds of Twitter time trying to understand it, the performers and their animals were the most important part of their lives,” he says. “It was a very crushing blow for anyone who knew and who had lived that.”

After talking with Powell, I head back to Feld to catch the last half of the day’s rehearsals. The trapeze troupe’s first attempt at the act is still hours away, but first, a young woman is supposed to climb into a new cannon for the very first time.

Into the Mouth of a Cannon

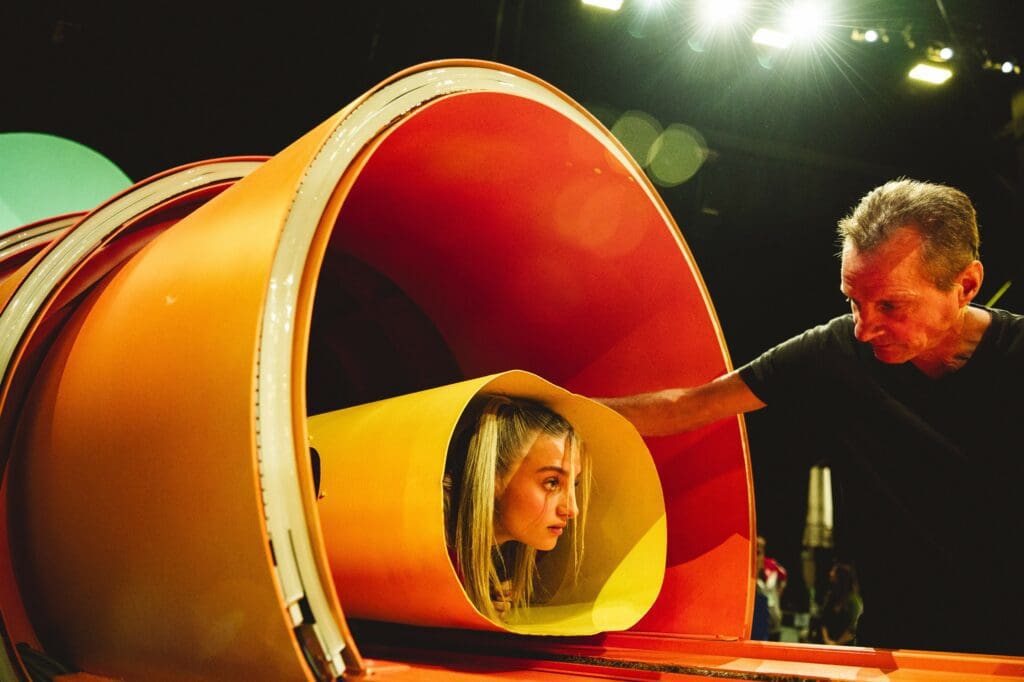

Just after lunch—the performers generally eat sandwiches and leftovers from Tupperware on couches in the green room—Brian and Skyler Miser stand with their arms crossed, identically, as if someone asked the father and daughter to strike the same pose. In front of them is a cannon, in a whole bunch of pieces.

Today was supposed to be the first time that 18-year-old Skyler Miser would crawl into the mouth of the cannon. This was supposed to be the day she’d fly the entire length of Ringling’s practice space, the day she’d land safely in a net at the end. But, her father says, “It’s got to prove itself to me first.”

Brian Miser spent most of his 60 years on this planet known as The Human Fuse, getting shot out of a cannon and a catapult at Ringling and on the Letterman show and probably 10,000 venues across the world. The plan had always been for him to hand off the cannon to his daughter. But the sudden

closure of Ringling meant Skyler instead worked at Subway after she graduated from high school.

Her earliest memory, from around 2 years old, is rushing over to the net to make sure her father was OK after getting blasted out of a cannon. “Yeah, it’s really dangerous. It’s not that the cannon is inherently dangerous, but he would light himself on fire too,” Skyler says.

She got shot out of a cannon herself for the first time at 11 years old. Brian sent a video of it to the Felds. He recalls, “They wrote back, ‘When she turns 18, we’ll have a contract waiting for her.’ And here we are.”

But this new cannon her father has built hasn’t been tested yet. They stood watching as a pair of Feld workers installed light kits inside the frame. When they’re done, perhaps in a couple of days, the Misers will begin by shooting out a sandbag that weighs about 100 pounds, the same weight as Skyler. During those first few tests, the sandbag shoots into the air dramatically, hitting 7 Gs, as much as a fighter pilot pulling out of a nosedive—0 to 55 mph in less than a second—only to smack spectacularly into the net.

Then they adjust the force of the new cannon, so the sandbag lands as softly as possible. When that happens, Skyler will climb into the new cannon for the first time, squat down into a compartment and hold her breath.

“Every shot we do, we have a logbook that documents how much the sandbags weighed. We write it all down so we can go back to it and figure out where we went wrong,” Skyler says.

Jumping Off Into the Unknown

In those final days of rehearsals before Ringling’s first show in September, it was like that for most of the acts, working out the timing of BMX jumps or honing the script of the actors who will create a storyline for the performance.

But none of it was as dramatic as the trapeze. It’s not just that it’s a headliner of the newly reborn circus, it’s also that an error would be potentially catastrophic, performers crashing into each other in the air, falling who knows where below.

For Caceres, this show is a culmination of a career. He told me by phone earlier, though, not to think of it as a culmination of a lifetime, a lesson he learned years ago.

Like many circus performers, Caceres was born into it. His grandfather was a clown in regional circuses in Colombia, South America. His mother, Clothilde, is a Ringling seamstress. His trapeze artist father, Miguel, created The Flying Caceres in 1982 for the 112th edition of Ringling. By then, Caceres was 4.

Back then, the performers would practice after the show, so Caceres remembers climbing that skinny rope ladder up to the handkerchief-size platform at 1 a.m. to join his father. He was 5 when he first started performing in shows, just a simple fly above the net, caught by the legs, upside down, then back to catch the bar. “It’s the most basic pass there is.”

He wasn’t afraid. “I remember feeling something. I wasn’t completely numb to it. But it’s like you don’t really know what could happen to you. You’re innocent. It’s later in life that you become really scared,” Caceres says.

In 1983, Caceres became the youngest person on the trapeze at the Monte Carlo International Circus Festival, beginning a career that spanned the globe. His father kept performing too, up until 2004. Miguel Caceres walked out, midshow, at a circus in Portugal. Something had just told him it was over, Caceres guesses. It wasn’t just that he retired—Miguel wouldn’t even talk about the circus or go see his son perform, not for years. Caceres reckons it wrecked his father to give up on the life, and he took it as a lesson.

Caceres is a performer now. He risks his life on a trapeze, but he also regularly reminds himself not to prioritize the circus above all else. Thinking of his father, he’s reminded to keep it just that, a job. He’s passionate about it, but he also keeps it in perspective.

“What sounds exotic for someone, it’s just my life. I try to just do a good job, whether I’m third or fourth generation. If it pleases my ancestors, great. It’s an added bonus.”

In creating his crisscross routine, Caceres set out to do something original. It’s based on an act first done at Ringling in the 1950s. But he added a new layer to the complexity with performers heading in two directions, an ending that has never been done before at Ringling, maybe anywhere.

While his troupe gets ready to try it for the first time, Caceres leaps out for his first trick, a simple maneuver not too far off from the one he did when he was 5. After Caceres returns to his platform, two performers set off just seconds apart, one from one side of the ring and one from the other. They cross in the center, leaping to the hands of the catchers who are hanging upside down on the swings. The two performers cross less than a second apart. As they swing out and back, two more performers take off from the platforms, Caceres is one of them.

Now things get difficult, dangerous. The first two performers swing from the platforms using the trapeze bars. They fly out into the hands of the catchers. As they do, a second set of performers swing out from the same bars, and then they trade in midair, the first set of performers returning to the bars and the second set into the hands of the catchers. They switch, just milliseconds, it seemed, from a collision. It’s like a pendulum swinging, only instead of one arm, there are four.

It seems like the end, right at that moment. But then they set off to do it a second time. At the end of the second attempt, instead of heading back separately, two performers jump to the same bar, so there’s four men on two bars, heading back to the platforms together. It seems like the bars could barely hold the weight, and they jostle and waver as they head upward.

Earlier, Caceres had explained that trapeze is a difficult act that looks easy, something that irks him. “I had a father-in-law tell me that I picked the wrong profession, that I should have found a job that looks hard and is actually easy.”

This, though, four men on two bars, looks impossible. They head back to the platforms with what seems like not enough momentum, as if they might just stall, right there, in midair. Their feet stretch skyward. They angle their midsections high. If they can just get their weight in front of them.

And then they land, all four of them almost simultaneously, up on the platforms.

As a journalist, I’m supposed to be impartial and objective. But I hollered just then, along with the crew and the casting director nearby. The performers join us, howling from up on the platforms.

Then they all take turns swinging out and leaping gracefully into the net. Down on the ground, they gather in a circle, hugging, high fiving, laughing. I ask Caceres how it feels. “Good. It always feels good to see something you created come to life.”

Some have wondered whether the circus can exist in a time of Instagram shorts and Boomerang loops. But that moment, when the crisscross trapeze came together for the first time, it felt more real and tangible than anything on a screen. Right there in front of us was “The Greatest Show on Earth.”