Artist Christopher Still Dives Deep Into Florida’s Legacy

Dunedin-born wildlife painter Christopher Still is running a race to lift up Florida's natural landscape.

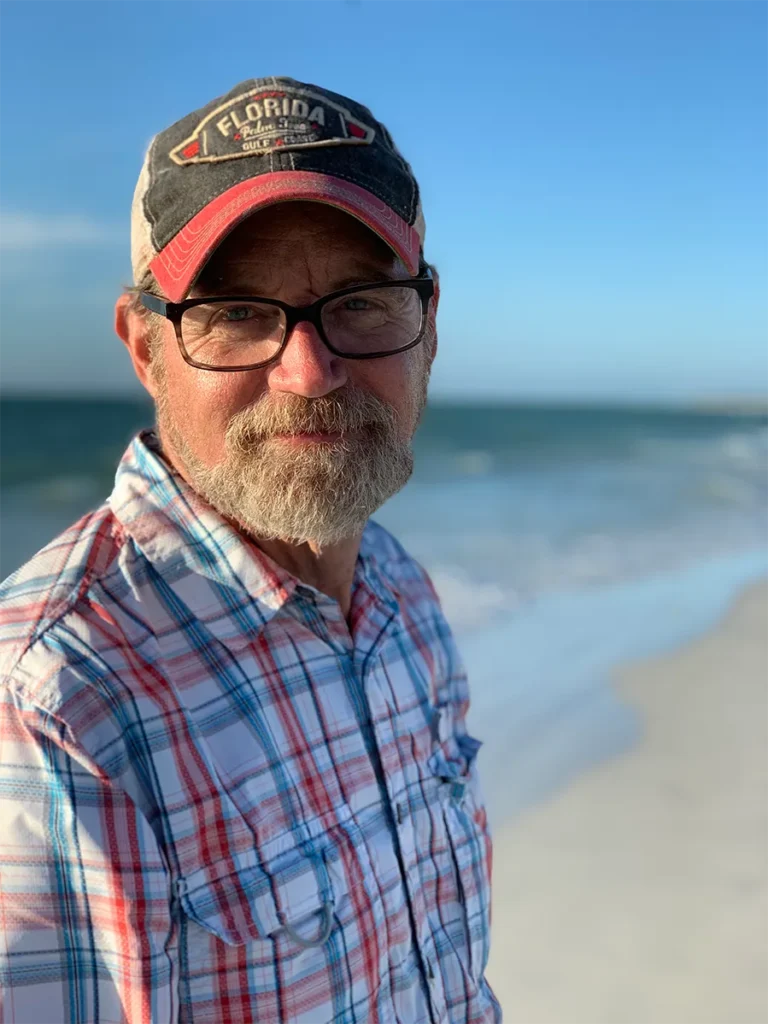

The ideal way to view one of Christopher Still’s massive paintings is with Still himself by your side. That way the artist, a slender and soft-spoken man, can point out all the hidden treasures—Florida history hiding in plain sight.

Throughout his creative process, Still crams his canvases with historical and environmental references—and at times has spent hours underwater using a waterproof box to create sketches that capture the light and movement of a spring.

To appreciate the result, consider the 8-by-8-foot painting that now hangs in the lobby of the AdventHealth North Pinellas medical facility in Tarpon Springs. The work “Beautiful and Historic Tarpon Springs” features a copper and brass helmet that Tarpon’s Greek sponge divers used to use in the foreground.

But without Still pointing it out to me one morning, I might never have noticed the map of Greece that shows up faintly in the shine of the brass.

Even more subtle is what he did with the Anclote Key lighthouse looming in the distance. Inside the top of the lighthouse stands a keeper holding something. It’s a love letter written in 1923 by one of the lighthouse keepers to the woman who would become his wife.

The man Still persuaded to pose as the lovelorn lighthouse keeper, lawyer Bill Vinson, is a descendant of the keeper’s family. Still said he made Vinson read the letter while he painted the tiny figure.

As for the results of the artwork, Vinson says, “Chris is very good at painting little, teeny things.”

Nearly every “little, teeny thing” in a Still painting has significance. He makes no apologies for hiding so many mind-blowing prizes amid the larger sweep of his subjects.

“I’m telling Florida’s stories,” says Still, who, at 49, was the youngest person to ever be honored as a member of the Florida Artists Hall of Fame.

Inspired by Wild Florida

Still is that rarity: a Florida native. He grew up in Dunedin. His mother was a textile artist and his father was a high school history teacher. His father went all out to make history come alive for his students, something Still cares about to this day. Still began taking art lessons at age 7 and sold his first painting at 14. He and his brother, John Jr., grew up exploring the woods near their home and playing in a nearby creek. Years later, Still came back to find the woods gone and the creek buried under a shopping mall. The memory of that loss drives him to document the state’s beauty and history.

“I feel like I’m in a race to lift up the Florida landscape before someone thinks they’re helping it by changing it into something else,” he explains.

He was 8 or 9 when his father took him to the tiny Panhandle hamlet of Panacea, where they met marine biologist Jack Rudloe at his Gulf Specimen Marine Lab. They had a lengthy discussion about Florida sea life.“ He started pulling stuff out of the touch tanks and showing it to me—sea hares and sea cucumbers,” Still says.

By the time he was a senior at Dunedin High, Still had twice won the Gold Key award in the local Scholastic Arts Competition. The sponsor, the Scholastic Corporation, awarded him a full scholarship to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia.

A Florida boy at heart, Still arrived in Philadelphia barefoot—and unprepared for winter. What made the academy worthwhile for Still was one of his teachers, Louis B. Sloan. Sloan was not only the first Black full-time professor at the academy, but he had been awarded a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship in 1963.

Sloan was an advocate of painting “en plein air,” which refers to the practice of painting outdoors with a subject in full view. Impressionists, including Claude Monet, often painted this way.

I feel like I’m in a race to lift up the Florida landscape.

—Christopher Still

On weekends, Sloan would drive Still and a few other students out into the countryside. They would spend the day painting the landscape while discussing techniques. Still, who until then had been accustomed to using graphite and charcoal to sketch studies, learned to paint directly from what he saw. From Sloan, Still learned a philosophy he follows today: “It is not what you paint, but how you paint it.”

Beyond the academy, Still took courses in human anatomy at Jefferson Medical School. Then, in Italy, he worked on the restoration of damaged frescoes at the Vatican, learning techniques dating back to the Middle Ages. Another scholarship allowed him to travel around Europe, visiting museums and taking careful note of the techniques of the artists.

Finally, he was ready to come home. But he found Florida wasn’t ready for what he wanted to do.

“Florida,” he explains, “has always had this self-esteem problem.”

An Artist Emerges

When Still returned home to Florida in 1986, he convinced a few people to hire him to make paintings. It didn’t hurt that the Tampa Museum of Art staged a one-man show of his work. People saw what he had done and sought him out.

Most of those early clients wanted abstracts or landscapes from someplace else. They didn’t want an artistic depiction of scenes they saw every day. Those didn’t seem special enough.

“Many of Florida’s subjects have been disregarded by the fine artist because there have been few examples of these scenes in museums,” Still wrote in a museum catalog for a retrospective of his work in 2008.

Slowly, Still began showing clients what he could do when they turned him loose. He could at last begin, as he put it in that catalog, “swimming in a gulf of history and marveling at the nature before me.”

By 1989, he had begun creating compositions like those of the old European masters he had once studied, painting local flowers, fruit and everyday items like keys, rings and watches. He also found ways to leave something seemingly sticking out of the frame, like an alligator’s jaw jutting beyond one edge, in a 3D effect. When this happens, Still once wrote, it’s him shouting to the viewer, “These things are real to me, and they can be real for you.”

Take a 1993 painting called “Land of Promise,” in the South Florida State College Museum of Florida Art and Culture’s collection in Avon Park. A young woman sits in the foreground, her back to the viewer, gazing at people gathered on the front porch of a pioneer homestead.

The cabin is real—it’s one that James McMullen built in Pinellas County in the early 1850s. It now sits in the county’s Heritage Village. The crowd on the porch are members of a wedding party. The girl in the foreground is the flower girl.

She’s seated on a colorful, hand-stitched quilt alongside fruit and a basket of flowers. The window that frames her is adorned with orange blossoms, a saw and a snakeskin. There’s a red lantern hanging above her head, while below her sits a Victorian-era woman’s boot, seemingly springing out of the painting.

It’s as if a Renaissance artist had leaped ahead centuries to depict a scene from Patrick Smith’s Florida-based pioneer novel “A Land Remembered.” It’s no wonder a 2011 museum catalog dubbed Still “Florida’s Dutch Old Master.”

Paintings such as this one were just a warm-up for his greatest challenge of all: showing the entire timeline of Florida history in one series of paintings.

It nearly broke him.

His Sistine Chapel

Florida built a modern state capitol building in 1977. Twenty years later, parts of it looked badly dated. House Speaker John Thrasher was determined to refresh the look of the lower chamber. He toured capitol buildings in several states and was impressed by the use of artwork to convey the history. Thrasher and the sergeant at arms, who supervised the facility, put out a call for artists to compete for the assignment of decorating the Florida House chamber.

“As I went through the work of those folks, there was only one, really, that stood out and would make a difference,” Thrasher said of the 30 artists who applied (in an interview that was part of a 2022 PBS docuseries “Florida Crossroads”).

This was Still’s dream assignment: Paint a series of interconnecting works that would depict the history of Florida from prehistoric times to the present day. But what Thrasher wanted was impossible. Still usually took a year to create one painting and collected a fee of $50,000 for it. The Florida House wanted eight of them in a year, and for just $150,000 total.

There was no way he could justify taking on the project, but he couldn’t stand to turn it down and see someone else do it, either.

“I thought, ‘This is me,’” he said later. “All my work was heading toward this. The Florida House of Representatives would be my Sistine Chapel. I refer to John Thrasher as my pope.”

He said yes and set to work, eventually taking four years to complete everything. He also had to sell additional paintings to private individuals to make up the money he would lose on the project.

He carefully mapped out how the paintings would progress through Florida’s eras, from the days when Native Americans roamed the woods and waterways to the launching of a space shuttle from Cape Canaveral. While covering a span of thousands of years of history, the lighting would change only slightly in each painting, so by the end it would appear that only 36 hours had elapsed.

He put out a call to friends who supplied him with the items he needed to supplement each scene—an enormous taxidermized raccoon, for instance. There are also subtle connections among the scenes and the items on display in each painting. For instance, in “Patriot and Warrior,” which features the fierce Seminole Tribe member Osceola in the 1800s, faint marks on the palm trees turn out to be depictions of several well-known Native American chiefs.

“All the paintings connect to one another, object to object,” Still says.

Some powerful people warned him to skip controversial parts of history. For instance, Still says, there were some who wanted him to omit Andrew Jackson, the state’s first pre-statehood governor and a staunch advocate for slavery. Thrasher told everyone to leave Still alone, ensuring the artist had a free hand.

Still painted Jackson holding a 23-star American flag, the one in effect in 1821 when he was governor. In the same painting, Still depicted an enslaved woman looking away from Jackson as if disgusted. Instead, she’s looking toward and pledging her allegiance to the current 50-star flag that’s not in any painting. It’s hanging behind the speaker’s lectern at the front of the chamber.

He created eight paintings with detailed historical settings, including one in which Still himself shows up as a steamboat passenger, a cameo worthy of Alfred Hitchcock. The eight historical paintings are followed by an additional two that carry the story beyond the land and beneath the waves. One is set at a coral reef in the Keys. The other shows life in one of the state’s remarkable springs.

This was before digital cameras made it easy to snap images of underwater scenery. At Still’s request, a friend built him a waterproof painting box with rubber gloves attached. He would put paper, several kinds of paint and some brushes in the box. Still would don scuba gear and descend to the floor of the ocean or a spring with the cabinet in three-hour stints. He would insert his hands in the box’s gloves and paint sketches of the reef or manatees. It was just like the en plein air paintings he’d done in art school, only the air was water.

He also spent weeks perched on a stool in the state’s Marine Mammal Pathobiology Laboratory in St. Petersburg, watching employees dissect manatees so he could learn their anatomy, says biologist Ken Arrison.

“Once he was finished with that painting, he brought it back for us to see, carrying it in a U-Haul truck,” Arrison recalls.

Look closely at the eye of the manatee in that final painting. Reflected in its dark eyeball is a view of the entire House chamber that surrounds the artwork. It’s as if the manatee is keeping an eye on Florida’s lawmakers.

Standing Still

To quite literally step into Still’s world, head over to the Tarpon Springs Heritage Museum. It sits on Spring Bayou, the scene of the town’s annual Epiphany celebration.

Since 2024, half of the building has been a tribute to Still.

On the walls hangs a mix of loaned originals and reproductions of his paintings, as well as key artifacts, like the waterproof box he no longer uses. In one alcove is a scene with a life-size cutout of Still next to an easel, which is set up as if he’s painting the landscape.

When I visited the museum with Still, there was a trio in a theater watching a short video about his career, methods and work. When they emerged, a woman in the group recognized Still, something that he says always blows his mind. She gushed about how much she loves his work and got his autograph. Of course, she had to have a picture.

She stepped into the alcove, flanked by two Stills: one a life-size cutout, frozen midbrush, the other very much alive. For a moment, past and present, Florida history and its storyteller, all lined up perfectly in her snapshot.

To find more Florida artists, click here.

About the Author

Craig has covered Florida’s quirks and creatures for Flamingo since 2016, writing about springs, panthers, manatees, python hunts and Ross Allen, the snake man of Silver Springs. He published his seventh book, “Welcome to Florida: True Tales from America’s Most Interesting State” in March 2025.