by | September 15, 2025

Why Mullet is Making Its Way Back on the Menu

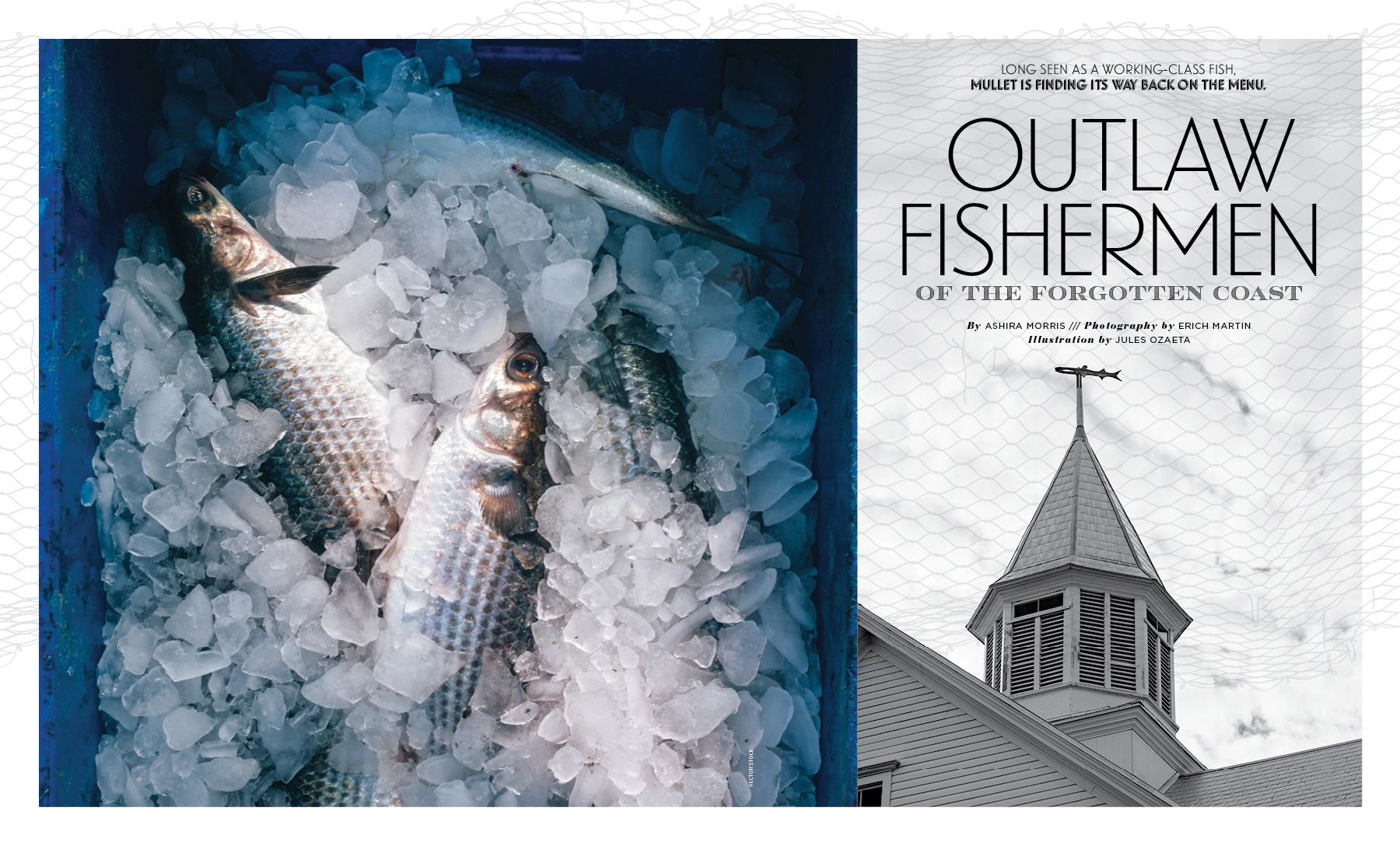

Long seen as a working-class fish, mullet is finding its way back on the menu in Florida's Big Bend.

Off the coast of Florida’s Big Bend, Leo Lovel steered his airboat, customized with a net table on the front for mullet fishing, from the dock at Spring Creek out into Oyster Bay. The Gulf Coast town gets its name from the springs that bubble fresh water into the salty bay. Spring Creek Springs and Wakulla Springs collectively put out the highest freshwater flow of submarine springs in the world, creating an ideal environment for oysters, fish and seafood.

Zipping across the water, the fan boat flew over mats of swaying seaweed and past flocking seagulls. Lovel, up in the elevated captain’s chair, pointed us toward the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge. On shore, stilted beach houses gave way to rows of narrow longleaf pines topped by branching crowns. There are only two things important enough for him to cut the motor to the giant fan and come to a stop: a site with fishing history and the mullet themselves.

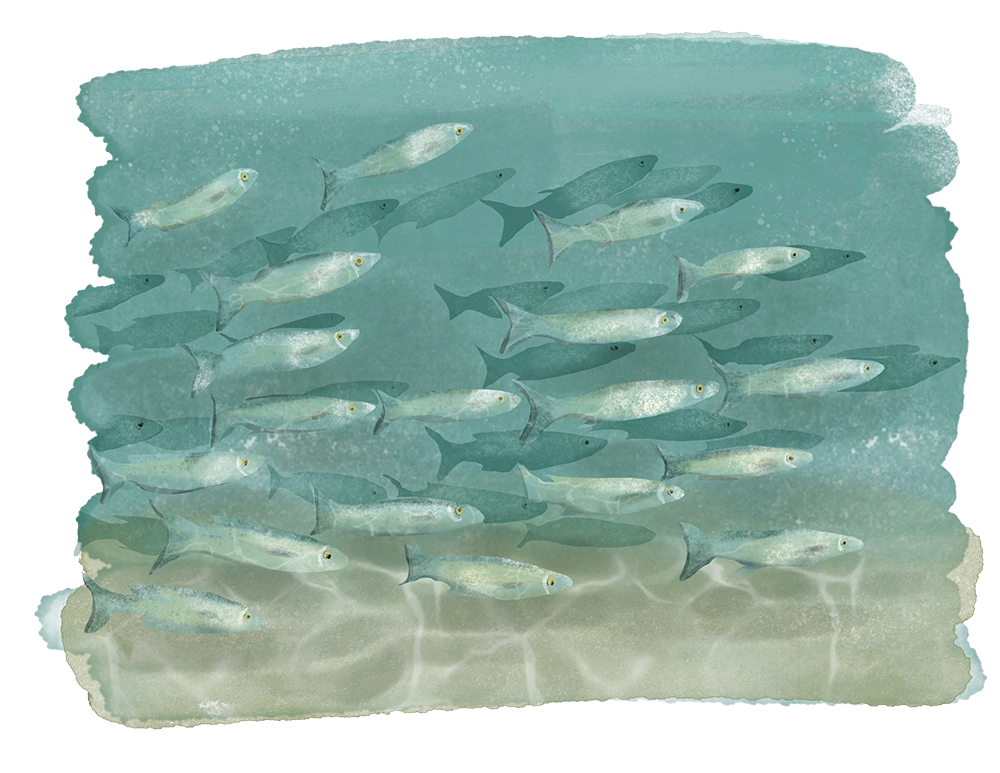

It was mullet run season: when the spawning silver fish migrate in massive swarms. These are the best mullet—fat from months of eating through the summer, perfect for smoking or salting. The female fish are full of roe.

Lovel pointed out a school of mullet in the water and asked if we saw it. At first, all I could take in was the expanse of clear spring-fed water glinting in the sun. Then a wide ripple in the water suddenly came into focus like a Magic Eye illusion as it moved against the waves. Lovel watched the fish wistfully. He would be reaching for a gillnet to strike them if it weren’t for statewide changes made 30 years ago to commerical fishing gear that banned the most popular way to fish for mullet.

Lovel has been fishing for mullet since the ’70s, when he moved down to the coast and took over the Spring Creek Restaurant with his wife, Mary Jane. Lovel says there isn’t a 200-yard stretch on this coastline he hasn’t covered.

For decades, mullet was the staple fish in this part of the Panhandle. It was what people ate locally, and it was what visitors came down to the coast to enjoy. At Spring Creek Restaurant, the Lovels served it the classic way: fried, with salt, pepper and cornmeal. When they started running the restaurant, Lovel needed up to 400 pounds a week of the fish. But by the time they closed after Hurricane Michael in 2019, the demand had dwindled to 50 pounds a week.

The changes can be chalked up to overlapping factors. The 1995 ban on gillnet fishing, passed by a statewide ballot measure, dramatically diminished the commercial mullet fishery. Commercial fishermen spent longer days on the water to catch fewer fish, resulting in higher expenses per pound caught. People’s tastes changed, too. According to Lovel, families used to eat mullet “like white bread.” But younger folks coming into the restaurant wanted shrimp and stone crab: “something with no bones in it.”

“We love to eat them,” Lovel says. “We love to chase them. We love to catch them. But I’ll put it this way: There’s nobody making a living or making any money off of it anymore.”

One Man’s Bait Fish

Mugil cephalus, more commonly known as the striped mullet, is a common fish found in warmer coastal waters, estuaries and rivers all over the world. Possessing glassy black eyes and silver scales, mullet typically grow to around 20 inches in length and weigh two to three pounds. They’re vegetarians that mainly eat microalgae and aquatic plant detritus. Their stomach has a gizzard-like structure, which allows them to grind their food. This anatomical feature led to a famous early 20th-century Wakulla County court ruling after a group of mullet fishermen was arrested for fishing out of season. The local county judge let the fishermen off the hook by proclaiming the mullet, with gizzards, were actually birds. The weathervane topping the Old Wakulla County Courthouse is shaped like a mullet in homage to the ruling.

The mullet along the crook of Florida’s Big Bend and across the Panhandle coast feed off the area’s mineral quartz sand bottom, giving them a better taste than the fish feeding from mud-bottom environments. Elsewhere, mullet is a bait fish—but along Florida’s Gulf Coast, the fish is a part of the culture.

“Mullet are so underappreciated,” says Angela Collins, a marine fisheries specialist with the University of Florida. “They’re super valuable to Florida’s history and have a lot of potential to continue to have value into the future.”

That history stretches back to the native population, who relied on mullet as a primary food source centuries ago. These early Indigenous peoples caught schooling mullet using natural fiber nets that were weighted at the bottom with stones, while the top floated with the help of buoyant plants.

In the 1800s, Wakulla County saw the emergence of seine yards—seasonal base camps for mullet fishermen, which came to life in late fall when the run season started. Fishermen would live on site for the six to eight weeks of the run season. Using nets weighted down with lead and buoyed by cork, the fishermen employed similar techniques to the Indigenous Floridians, flinging arcing nets to haul thousands of fish to shore.

The mullet were salted and put in barrels. Before refrigeration, the fish were traded with farmers in South Georgia for land crops like sweet potatoes. Barrels of salted mullet were loaded onto trains in Sopchoppy and other coastal depots and sent north. On site at the seine yard, fishermen fried mullet for camp-wide communal meals.

David Roddenberry, whose book “Historic Seine Yards of Wakulla and Franklin Counties” documents the sites, grew up in the small town of Sopchoppy, not far from Spring Creek and the fishing camps he writes about. When he was young, he remembers a man driving around town selling mullet off the back of his truck, freshly caught the night before and weighed out on a scale in the truck bed.

In Roddenberry’s lifetime, the fisheries boomed. Initially, the main value of mullet was for its meat, with demand for the fish primarily located within Florida. In the 1960s and 1970s, the state attempted to promote the fish and create a national market. First, the state formally renamed the fish “lisa” to avoid the trash fish association. When that didn’t work, the state tried a different tactic.

“For good eating, many commercial fishermen prefer mullet over all other fish,” a Florida Mullet Recipes pamphlet from 1968 proclaims. “With this endorsement, you should give mullet a try.” In 1968, the Florida Board of Conservation produced an educational film called “Mullet Country.” Opening with footage of wild Florida waterways and happy young couples making mullet at a beach cookout, the film sold mullet as a cosmopolitan food that could be served at “fashionable gatherings.”

“Do you have mullet in France?” a man in a dinner jacket asks a French woman while playing chess in a later scene. “Oh yes we do,” she assures him. However, despite all the state’s efforts to market mullet to Americans beyond Gulf Coast Florida, what ultimately drove the fish’s popularity was an international demand for mullet roe.

Well, they did it. And it turned all of us into outlaws.

—Leo Lovel

“It suddenly became a super high-value commodity fish because they were fishing for roe that they were then exporting,” Collins says.

Floridians hardly considered roe to be a luxury good—some spots along the coast sold roe and grits for breakfast. But exports to France, Japan, China and other markets caused a bonanza. Lovel remembers Spring Creek being like “the wild wild west” in the ’80s, with out-of-towners showing up to fish

and earn money.

“Basically, if somebody offered them just a shelter over their heads, food or cigarette and beer money, they got you,” he says. “It was crazy, wild, rough, tough. It was so much fun.”

Turning Tides

In 1992, Lovel was asked to attend a meeting held by the Department of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources in Tallahassee. There was one item to discuss: a proposal to ban net fishing throughout Florida. When he returned to Spring Creek and gathered other fishermen to share the news, they laughed. It couldn’t be true.

“Well, they did it,” Lovel says. “And it turned all of us into outlaws.”

Two years later, Floridians voted in favor of Amendment Three of the Florida Constitution on the November 1994 ballot question. The movement was spearheaded by the Coastal Conservation Association of Florida and Karl Wickstrom, the founding publisher of Florida Sportsman magazine, in an effort to limit bycatch and promote sportfishing interests. Commonly referred to as “the net ban,” the ballot initiative enshrined in the state constitution a restriction on specific types of fishing gear, prohibiting gillnets in all state waters and only allowing nylon nets of up to 500 square feet in near-shore and inshore waters.

The mullet fishery, specifically in the Panhandle, played a significant part in what ultimately led to the ballot question. At the time, the Gulf Coast area was the biggest segment of the inshore fishery. Mullet roe alone could bring in millions of dollars in a season. Lovel remembers putting up to 10,000 pounds of mullet on trucks bound for New York twice a week.

Leo Lovel shared his tips and tricks to frying mullet. Click here to find out what they are.

The state fisheries commission was stuck, unable to pass any measures without pushback. There were also concerns about bycatch, when fishing nets accidentally entrap other species. The end result was a blanket ban that cratered the commercial mullet fishery.

Many fishermen in the Spring Creek area remain upset at the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, which enforces fishery rules. Individuals like Lovel continue to be frustrated by what they say was a prioritization of recreational fishing, development and higher-end tourism money over the working industry.

“We got to participate in historical cultural change,” Lovel says. “We just didn’t know at the time.”

Fish of the People

In the two years after the net ban, landings for mullet—or the weight of fish caught and brought to market—dropped to 7.3 million pounds from 18.5 million pounds collected in the two years prior. Dockside value for mullet dropped by 50%, while the price per pound increased by nearly 20 cents. Researchers say more studies are needed to understand the net ban’s effects fully. These days, it’s not as easy to find fresh mullet at a fish market, but a handful of shops still sell it. Nichols and Sons Seafood in Crawfordville is one of them. Their regulars have been buying mullet here for ages, owner Roger Noe says while standing outside the small white cinderblock building. There’s no sign, but people consistently pull up to buy fresh catch. Mullet is one of the cheapest on the board.

Noe mostly sells to restaurants in the region, and, like Lovel, he’s seen the mullet demand decline from 20,000 pounds a week to 5,000.

“The older people are the ones who eat mullet,” he says.

When Noe was younger, his dad would take him out mullet fishing. He kept a Dutch oven, cornmeal and grease on board so they could fry the fish as soon as they caught it.

Mullet are so under-appreciated. They’re super valuable to Florida’s history and have a lot of potential to continue to have value into the future.

—Angela Collins

Ask most fishing folks their favorite way to eat mullet, and they’ll tell you that fried is the only way, served with grits or hush puppies. Most seafood shacks serve it like this along Coastal Highway 98, which runs along the Gulf through mullet territory.

If not enjoyed freshly fried, the other classic preparation is smoked mullet dip. The savory spread is one of the two original items on the menu at Mineral Springs Seafood in Panacea, whose signboard on U.S. 98 reads “That place with the dips.” Tim Williams, who took over the storefront from his parents 18 years ago, stopped offering fresh mullet as soon as he was in charge.

“It tastes like guts to me,” he says. “I had to eat so many of them growing up. I’d rather eat the box they come in.”

But the popular smoked mullet dip remains a staple at the roadside market—Williams acknowledges he has to have it for the locals. During run season in the fall, when the fish are fattest, Williams smokes enough mullet in the shack next to the store to make 400 pounds of dip every week.

Any seafood restaurant along the coastal highway worth its salt still has mullet on the menu.

“If you go to a seafood place here and it doesn’t have mullet, there’s probably something wrong,” says Thomas Derbes, a chef and Florida Sea Grant extension agent working with commercial and recreational fishers in Pensacola.

While most places around Spring Creek go for the traditional preparation—fried whole or smoked as dip—a few hours west there’s been experimentation. Derbes worked as a chef at the now-closed Kingfisher in Pensacola for two years, where he saw how much the community liked mullet. The restaurant hosted regular pop-up dinners; for one of the events, Derbes remembers he and the other chefs “just did something crazy.”

Mullet sushi had arrived.

“It was a hit,” he says. “People showed up for that.”

Learn how to make Chef Ian Hill’s mullet sushi at home.

Derbes sees younger people excited about eating the fish as well, not just older folks. In March of this year, Derbes co laborated with the University of West Florida’s Archaeology Institute on an event called “A Mullet Story: Cast Nets and Cooking Traditions.” Taking place at the Museum of Commerce, the event featured expert talks on mullet’s cultural importance in Florida. Guests were able to try a range of dishes prepared by Derbes and other guest chefs, including old-school mullet and grits as well as mullet-topped oysters. Derbes went more modern with fried mullet sliders.

When he’s cooking for himself, Derbes says he’s a fan of bottarga—cured mullet roe, which has a rich, salty flavor and can be enjoyed shaved on top of dishes. Mullet has a reputation as a working-class fish—the fisherman’s fish. But the tides (and tastes) could be changing.

“I don’t think it was always that way,” Collins says. “And it doesn’t have to stay that way.”

For anyone, of any age, with a hankering for the flavors of Florida’s Gulf Coast, mullet is as close as it gets, no matter how it’s prepared.

“It’s a fish of the people,” she says. “All of the people.”

Mullet Memories

Back on my tour of Oyster Bay with Lovel, he stopped his airboat along the way to point out several sites from the past. Not far from the St. Marks Lighthouse was Nat’s Point, an “iconic run stand,” where boats would line up ove night to have a good position the next morning in order to get first dibs on striking the fish coming down the shoreline. We cruised by what remained of the West Goose Creek seine yard, which had been all but leveled by Hurricane Kate in Nov. of 1985. We paused by wooden drying poles still standing sentinel over the marshland—Old-Florida relics from the days when fishermen would hang their flax cotton nets so they wouldn’t rot.

As our time on the water came to a close and we made our way back toward Spring Creek, Lovel cut the engine once more. A small school of mullet rippled in the water nearby. Lovel threw a green nylon cast net out into the creek—the legal way to fish these days—and started maneuvering the airboat in wide circles so the net would spiral “like a cinnamon roll” with the fish as the filling.

When the net was tightly wound, he started reeling it back up onto the bow of the airboat with mullet and bycatch trapped in the mesh. Lovel deftly removed the fish from the mesh, tossing trout and butterfish back into the water. On the dock, he worked through the fish. Before the net ban, Lovel would clean hundreds of pounds of mullet a week. It was a chore. After the ban, the task took on different meaning.

“I thoroughly enjoyed cleaning every mullet that I caught,” he says. “I would sit there and say to myself, you know, ‘I’m still here. I’m still catching fish.’”