by | August 30, 2025

More Than Mascots: How 3 College Icons Became Football Legends

Meet Florida's sideline superheroes and learn the history behind FSU, UF and UM's mascots.

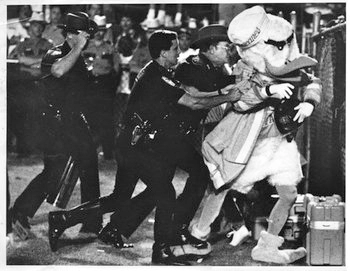

It was 10 minutes before kickoff on a crisp October night in 1989. The Miami Hurricanes were set to play the Florida State Seminoles at Doak Campbell Stadium in Tallahassee. The two schools, both ranked in the top 10, shared a notorious in-state rivalry. As the University of Miami’s (UM) football team stormed the field, a Leon County sheriff’s officer noticed someone out of place in the lineup and grabbed the offender. Four other police officers joined in, pinning the culprit against the fence but struggling to snap handcuffs on his unusual frame. The five officers found themselves in a scenario the academy hadn’t covered—how to arrest a 6-foot-tall ibis.

“I was detained. I was never arrested,” says John Routh, who played UM’s lovable and mischievous mascot Sebastian from 1984 to 1993. “That’s the key phrase, ‘detained.’”

On that night, Routh had borrowed a fireman’s hat, jacket and extinguisher before the game. He had one goal: snuff out Florida State University’s (FSU) burning spear, carried by Osceola, the school’s signature Seminole warrior who rides his horse Renegade onto the field during FSU’s pregame ritual.

As Routh tells it, when he ran out of the tunnel, he was yanked to the side. The beak on his costume limited his vision, and he couldn’t see that he was tussling with law enforcement. The man with the badge and the Bird then began a game of tug-of-war over the fire extinguisher, causing it to spray right into the chest of a Leon County sheriff’s deputy, earning Sebastian a five-man takedown. The deputies eventually released Routh but stopped him from going any farther while FSU’s Osceola planted a spear on the 50-yard line.

“To this day, when Miami plays at Doak Campbell Stadium, a Leon County sheriff’s deputy will search out and keep Sebastian off the field until after (Osceola) does his thing,” Routh chuckles. “So I guess you could say I kind of created that tradition.”

It’s game-day traditions like this that ignite passion in college football fans across the nation. Every fall, hundreds of thousands descend on Florida stadiums not only to watch their team play to win, but also to revel in the pageantry—the drumlines, the chants, the cheers, the chomps and the chops. And at the center of it all, stirring pride with every wave, dance and stunt, are the mascots. These characters are more than sideline jesters. In a state where college football rivals religion, they are icons of identity brought to life by the people who wear the suits, ride the horses and carry the torches.

Feathers, Fur and Fan Psychology

Turns out all that stomping, chanting and mascot mayhem isn’t just for show—it’s rooted in science. In a research article published in 2022, University of Florida professors of sports management Yong Jae Ko and Younghwan Chang found that mascots attract new fans and strengthen the relationship between existing supporters and sports teams. When people see a mascot, they attribute human-like characteristics to the school it represents. This forms a psychological and social relationship between fan and team. And much like the importance of national morale when a country is at war, the mascot’s job is to rally fans to support their team, win or lose.

During his reign at Miami, Routh was no rookie at building morale. “At the time, I think I was the only professional mascot in all of college (sports),” Routh says. Routh started his career as Cocky, the spirited representative for the University of South Carolina, while he was a student there in the early ’80s. After he graduated, he was hired as the Miami Maniac, a mascot dedicated to UM’s baseball team. The university then asked Routh to help revamp the Miami football mascot, and Sebastian the Ibis soon became known for his stunts. The bird knew how to make an entrance—picture helicopters flying into the Orange Bowl and speedboats cutting across Biscayne Bay.

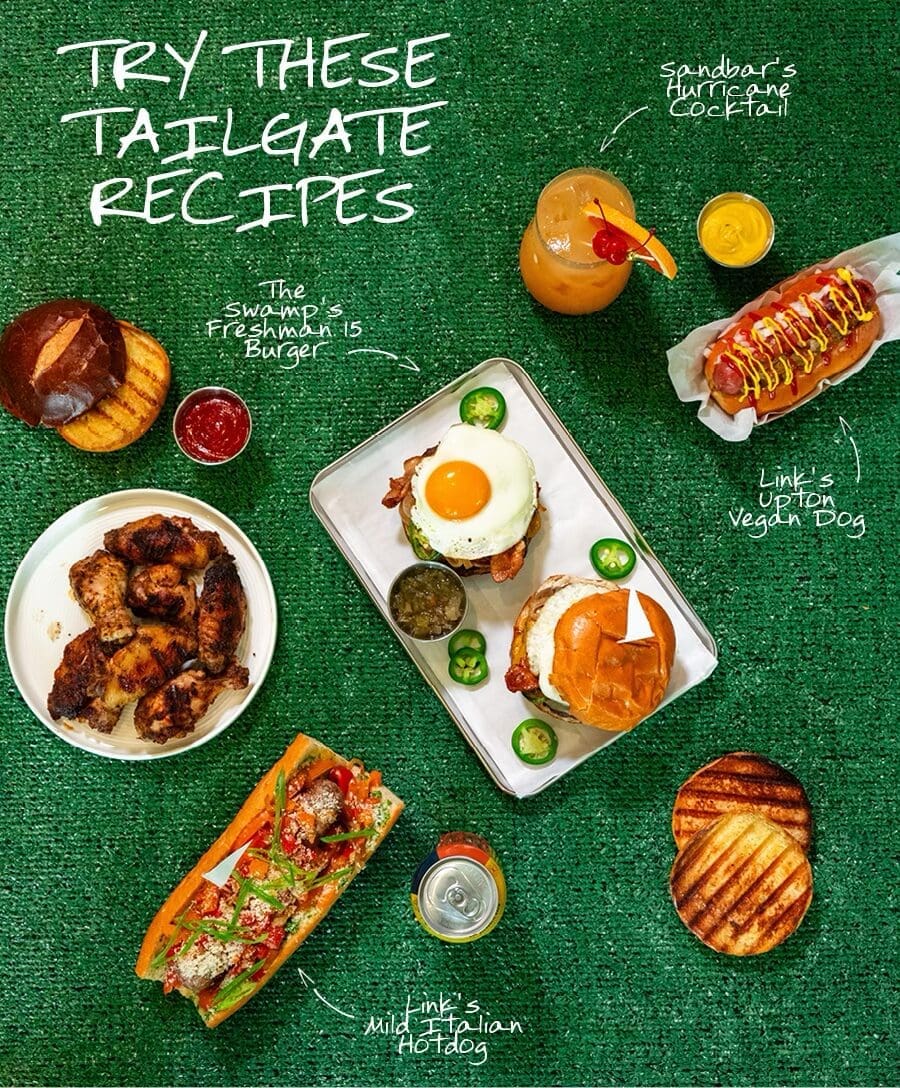

CLICK HERE for tried-and-true tailgate recipes from three of the biggest college towns across the state.

Routh was ruffling feathers and making his mark on Miami. Before his first-ever game as Sebastian in 1984, Routh asked where he could change into the mascot suit and was directed to the football players’ locker room. It also happened to be the first game for the team’s new head coach, Jimmy Johnson. Johnson was walking around the locker room, slapping players on the back and prepping them for the hours ahead, when he came upon Routh sitting next to his beaked helmet. Routh introduced himself as Sebastian, Miami’s mascot. Johnson, who would go on to coach the Hurricanes to a perfect 12-0 season and national championship in 1987, was shocked that the mascot dressed with the football players.

“And I said, ‘Yes sir, it’s a tradition at Miami,’” Routh says. “Well, the tradition started right then and there.” This continued for the rest of Routh’s time at the U, leading to friendships with the players and touchdown celebrations involving Sebastian on the field.

Fans also have Routh to thank for the iconic C-A-N-E-S spellout cheer. Once the stadium reaches a near brain-rattling decibel, Sebastian signals the chant, and fans spell out Canes in a sharp staccato. “I had tried to do it when I was at South Carolina, but trying to spell out C-O-C-K-S is a little more difficult,” Routh laughs.

After his nine-season reign as Sebastian ended at the end of the 1992 season, Routh’s ties with the school only strengthened. He now works as the executive director of the UM Sports Hall of Fame & Museum, and he attends Canes’ games to see his old pal Sebastian and his female counterpart, Gigi, firing up the crowd. Routh even cheered on the Bird when Sebastian was inducted into the Mascot Hall of Fame in June.

Under Century Tower

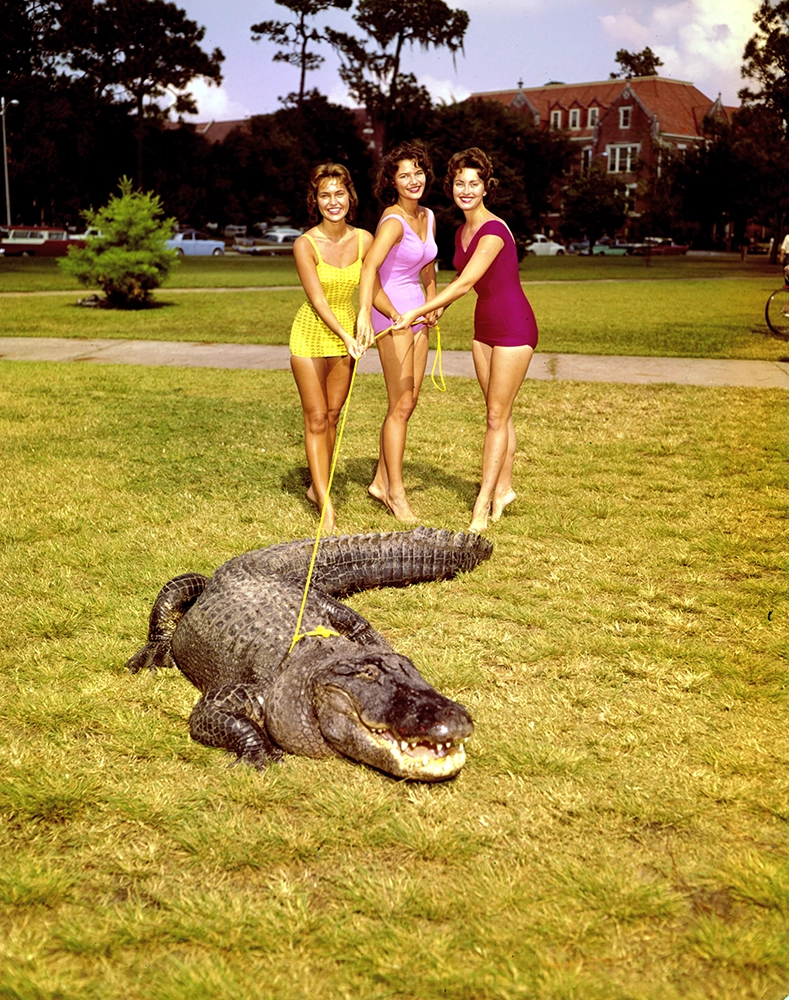

While most college mascots are plush, padded or—in Sebastian’s case—feathered, the University of Florida once took a more literal approach. From 1957 to 1970, UF used live American alligators as their mascot—although, there are records of the tradition from long before. Albert the Alligator’s first documented home was in the backyard of the Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity house, and later in a pen near Century Tower, the 157-foot-tall bell tower situated in the middle of campus.

Being the face of Gator Nation wasn’t easy. Albert endured students throwing cigarette butts and beer bottles in his pen, rival kidnappings, prank paint jobs and outlandish stunts. These antics twice turned deadly: first in 1954, when Albert was found beaten to death in his pen, and then in a shocking 1965 incident when a later alligator successor was shot near the eye. In 1970, the fifth live Albert alligator was released into Lake Alice, a small body of water on campus. Later that year, the university introduced a costumed version—later joined by Alberta, his orange-bowed female counterpart.

Decades after Albert and Alberta debuted their softer side, UF student Kourtney LaPlant spotted an ad for the mascot auditions in the school newspaper and thought, “Why not?”

As a freshman, LaPlant had to pass three stages of tryouts: a personal interview, a skit in the mascot suit and an improv session to see how she would react in realistic, unexpected situations. She succeeded, portraying Alberta from 2001 to 2005 and becoming a Friend of the Gator—UF’s secretive mascot program. Her then-boyfriend and now-husband, Brian, auditioned a year later, suiting up as Albert from 2002 to 2005.

“Sometimes kids are scared of us,” Brian says. “Sometimes it was unruly fans.”

Though the two dated off the field and eventually married, their characters are officially “just friends”—a running debate among Gator loyalists and loathers alike.

“It’s something we can say we did together as a couple,” Kourtney says.

Kourtney was a female mascot when women’s sports were still burgeoning. The university introduced its women’s soccer team in 1995 and softball team in 1997, among other women’s sports.

“We had to fight to get equal footing for some appearances, especially at football games,” Kourtney explains. “One thing that was kind of a struggle for me was away football games. Home football games, both of us go. Away football games, Alberta never traveled with the team—just Albert. It really makes me proud now to see Alberta going to away games. I think it’s really changed for the better, and I’m happy for that.”

Today, the real-life couple lives with their two children in Gainesville and has season tickets to The Swamp, watching every home football game and catching up with other former mascots and friends at the F Club, an exclusive lounge for former UF athletes.

“We have a tradition,” Kourtney shares about her family. “We don’t leave games early, win or lose. We always make pregame. We stay till the last second, and we always sing the fight song at the end of the game before we leave.” The LaPlants, like many others, like to relive the glory days while feeling like a small part of something much bigger in the present.

It’s hard for the couple to believe that 20 years have passed since they last took the field as Albert and Alberta, but the LaPlants still feel the same excitement in the stadium as if they were performing on the sidelines. “The energy of Gator Nation is pretty hard to beat,” Kourtney says.

Unconquered

Jeff Ereckson remembers the first time he saw FSU fans do the Chop. It was Oct. 13, 1984, and the FSU Seminoles were playing the Auburn Tigers in Tallahassee. The stadium was packed, and Ereckson, who served as Osceola from 1983 to 1984, felt it shaking from the roar of the crowd. According to Ereckson, the Marching Chiefs, FSU’s band, were sitting close to the student section and blocking the view of a group of fraternity brothers. The frat guys kept motioning for the band to sit down, waving their arms to a thrumming beat. Other fans saw the movement, and it caught on, he says.

“That’s kind of how it evolved. At the time, you had no idea it would become a tradition,” says Ereckson, now the Director of Development for FSU’s College of Arts and Sciences. “And of course, as time went on, it certainly has. It’s also become a part of FSU lore.”

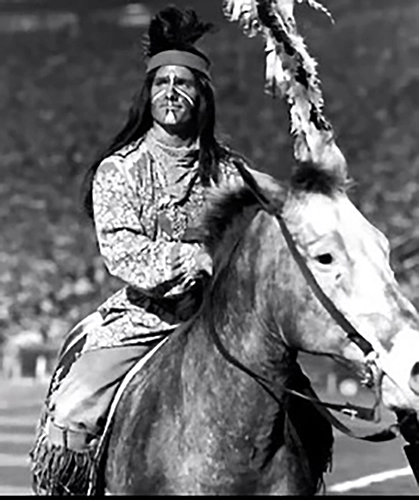

The university officially does not have a mascot, insisting that Osceola and Renegade are symbols that “pay tribute to the resilience and courage of the Florida Seminoles” Tribe. Osceola refrains from cheerleading during games, being subject to parameters set by tribal partners that control how the pair can be depicted. The Seminole Tribe of Florida—known for never signing a peace treaty with the U.S. government—has been a symbol of strength for the school since FSU adopted the Seminole name in 1947. But that early adoption came without the Tribe’s blessing. For decades, the university used sweeping Native American stereotypes in its imagery: tomahawks, warbonnets and teepees.

That changed in the 1970s, when FSU began a partnership with the Seminole Tribe of Florida to move toward a more respectful representation. The modern Osceola pregame ritual was born in 1978 when FSU alum Bill Durham created a proposal to honor the historical figure. Durham presented the idea of a horse and rider to FSU’s then-head football coach Bobby Bowden and got his support. Durham then went to Seminole Tribe Chairman Howard Tommie, who signed off on the proposal and provided consultation to ensure an accurate presentation. Osceola and Renegade have since become an iconic expression of FSU’s culture, recognized around the world as a living tribute to the unconquered spirit of the Seminole Tribe of Florida. To this day, the Tribe works closely with the Osceola and Renegade pageantry program, creating authentic apparel for the men portraying the legendary warrior.

Before Ereckson first wore the war paint, he spent two years as an apprentice. “You may remember how Coach Bowden used to go about with training his quarterbacks,” says Ereckson, referencing the championship-winning coach’s practice of making true-freshman quarterbacks wait two years before allowing them to step foot on the game-day field. “That’s the kind of approach that we use with the Renegade team as well.”

For his freshman and sophomore years, Ereckson spent a minimum of three days a week mucking out stalls, riding the Appaloosa horse at secret training grounds and forming a bond with the animal. “You’ve got to get to know the horse. The horse has to get to know you,” Ereckson says.

During their pregame ritual, Osceola, atop Renegade, charges the field while hoisting a burning spear over his head. When the duo reaches the FSU logo at the 50-yard line, Renegade rears up, and Osceola plants the flaming spear into the turf. The ride onto the field is no small feat. Unlike traditional saddles, Renegade’s uses only a blanket and girth—no stirrups—requiring incredible leg strength.

“When you ride a motorcycle, you know where the gas is, (where) the brake is, and you realize that everything is up to you,” Ereckson says. “When you’ve got a horse, it’s different.”

Horses can be wary of new people they don’t recognize, which isn’t ideal in game-day situations. A strong relationship with the animal is key. To build trust with his Renegade, Ereckson fed the horse sugar cubes during their time together. “The more they know you, the more they like you, the more they’ll respond to you when they need to,” Ereckson explains.

Ereckson looks back fondly on his time portraying Osceola. He’s grateful for the opportunity to embody FSU’s spirit and pay tribute to the Seminole Tribe of Florida.

“You’re part of the tapestry, if you will. You’re woven into it all,” Ereckson says. “You’re part of the experience. And it makes me proud to say I was a part of it.”

Homecoming

Back at UM, Routh recounts his final game as Sebastian—a memory that hasn’t faded even though his scar has. It was New Year’s Eve, the night before the 1993 Sugar Bowl. The Hurricanes were in New Orleans to face Alabama. Routh and a group of other Canes fans were singing their fight song on Bourbon Street with kazoo accompaniment.

“We were doing the Miami fight song and bam!—something just kind of hit me in the face,” Routh says.

A stray bullet had struck his temple and exited through his cheek. He later learned he was the first gunshot victim of the night, the result of an ongoing practice among gangs in the area to fire celebratory rounds across the French Quarter to celebrate the New Year. Thirteen stitches later, Routh still suited up for the big game, wrapping Sebastian’s helmet in matching bandages.

“Well, it’s gonna take a hell of a lot more than a bullet hole in the head to keep me out of this game,” Routh said to ABC announcer Bob Griese in an interview at the time.

Now, decades removed from the sidelines but never far from the action at the U, Routh still taps into the power of the traditions he helped build.

“You can’t know where you’re going until you know where you’ve been,” Routh says. “The world changes a lot, but it’s nice to have something that’s familiar. Something that brings back memories and makes you realize at a football game, it’s like being home again.”

That feeling of homecoming hits Routh every time he sees a football team take the field or when he walks the UM Sports Hall of Fame & Museum, where Sebastian lives on—and where he keeps that fire extinguisher from 1989 on display.

For more stories on fascinating Floridians, click here.

About the Author

As a born-and-raised Floridian, Emilee loves to write, read and talk about the Sunshine State. She graduated from Florida State University with a degree in editing, writing and media. Now, Emilee uses her skills to edit our print issues and online content, as well as write our weekly e-newsletter, Fresh Squeezed.