by Craig Pittman | March 10, 2025

The Storied Past Behind the Crystal River Archaeological State Park

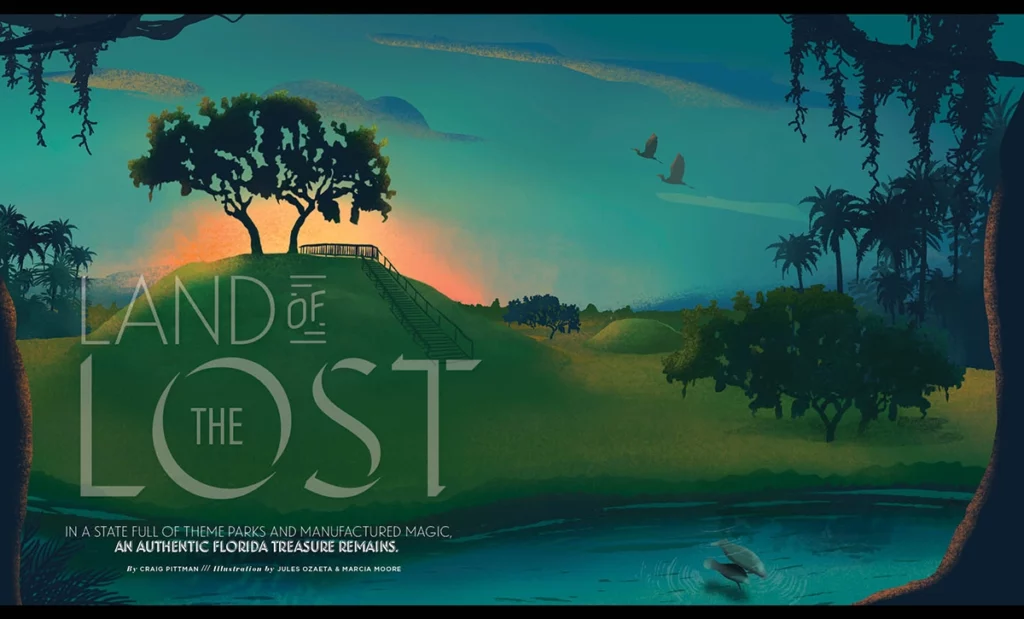

In a state full of theme parks and manufactured magic, an authentic Florida treasure remains at Crystal River Archaeological State Park.

When I reached Crystal River Archaeological State Park, I threw my car into a space and immediately set off striding toward the highest spot for miles around. The day was cool and clear—perfect for pretending to be on a trip into the distant past. I passed lots of families strolling around the park, the children chattering with excitement, while I made a beeline for my objective.

Minutes later, I stood by the first of the steps leading to the top of what’s known as Temple Mound A. I took a deep breath and started to climb.

A 51-step staircase allows visitors to scale the top of the temple mound, if they haven’t neglected leg day at the gym. It’s Florida’s version of the Egyptian Pyramids—almost as ancient, only not quite as tall.

When I made it to the top, huffing and puffing a little from the climb, I found two others who’d gone ahead of me. One was sitting down to catch his breath after such an ordeal. The other man was on his feet and eagerly snapping photos, astounded at how far he could see. I imagine the view hasn’t changed all that much from when this earthen mound at Crystal River Archaeological State Park was first erected thousands of years ago. But like many of Florida’s authentic treasures, the hallowed perch was almost lost to modern man’s shortsightedness.

Storied Lands

As U.S. 19 rolls through the landscape north of Tampa, it passes by some quintessential Florida attractions you won’t find anywhere else.

You’ll see some impressive fakery. There’s Weeki Wachee Springs State Park, which has made its name paying performers to put on phony tails and swim around acting like mermaids. You’ll see the historic gas station that’s made to look like a fake dinosaur in Spring Hill. Then there’s a ginormous manatee statue at Ellie Schiller Homosassa Springs Wildlife State Park. The park is also the home of Lu the hippo, an official citizen of Florida despite his kind being from somewhere far away.

But if you want to feast your eyes on something truly authentic, turn in at the sign for Crystal River Archaeological State Park, one of the most interesting places to visit in Florida.

This 61-acre riverfront site just off U.S. 19 contains six pre-Columbian burial and temple mounds. It was one of the longest continuously occupied locations in Florida. Is it any wonder that it was named a National Historic Landmark in 1990?

There aren’t many such sites in as good a shape.

—Thomas Pluckhahn

In 2023, Crystal River Archaeological State Park drew 40,961 visitors, but there should be a lot more. Elissa Hofelt of the Citrus County Visitors Bureau called it “a hidden gem, because not a lot of people know about it. It’s absolutely gorgeous … The top of the mound is one of my favorite spots in Citrus County. The panoramic views are so relaxing and fabulous.”

She said her organization recently played host to the leader of a German travel agent group who was touring the region. She enjoyed seeing Crystal River’s best-known attraction—manatees—but what really wowed her was Crystal River Archaeological State Park.

“I showed her around the park, and she was enthralled,” Hofelt said.

Scientists feel the same way.

“It’s a really unusual site,” said Thomas Pluckhahn, a University of South Florida anthropologist who’s done extensive research on Crystal River’s mounds. “There aren’t many such sites in as good a shape.”

No one knows for sure why the occupants chose that location for habitation, he said. But there are theories. No one had built roads back then, so the site’s proximity to Crystal River probably made travel by canoe up and down the coast easier. Boat access to the Gulf of Mexico was easy from there, too. Plus, the river and its adjacent coastal marsh provided access to the seafood the inhabitants primarily dined on. “Also,” he said, “it’s kind of a junction between trading routes.”

Without A Trace

Not only was this site occupied for more than 1,000 years, but the evidence shows people traveled thousands of miles to visit Crystal River every year.

They did not stop in for souvenir T-shirts, roller-coaster rides and funny postcards, the way we moderns do with our theme parks. Back then, visitors came to conduct trade, celebrate events and bury their dead.

“People traveled to the complex from great distances,” the state park’s website says. “It is estimated that as many as 7,500 Native Americans may have visited the complex every year.” Meanwhile, roughly 100 lived there year-round.

We don’t know a lot about those visitors. Nor do we know much about the villagers who received them, except that they “were kind of like cultural brokers—middlemen in the trade between regions,” Pluckhahn said.

They had no written language to record their hopes, their dreams and the details of their trade. They left us no books or tablets that described what life was like here before the current 23 million residents showed up, although it’s obvious that the traffic was better and housing more affordable.

Those early inhabitants and their unusual home on Crystal River did inspire bestselling Florida science fiction and fantasy author Piers Anthony’s novel “Tatham Mound.” The book is about a young warrior on a mission to unite the tribes of Florida and Central America against explorer Hernando de Soto and the invading conquistadors. But Anthony’s timing is off, because this site pre-dates the Spanish arrival.

Radiocarbon dates from the lowermost levels in recent excavations suggest that people began to live at Crystal River sometime around 500 B.C. Other on-site evidence suggests that groups had congregated at the site to participate in ceremonies for hundreds of years before that and then began staying there for longer intervals until they made it a permanent settlement.

Then, between A.D. 200 and 300, the village expanded greatly in size and permanence. But eventually, hundreds of years after it first began, perhaps around A.D. 970., the settlement faded from existence for no obvious reason.

The villagers were gone by the time de Soto and the other tin-hatted Spanish explorers arrived in Florida. Their buildings, likely made of some sort of wood, rotted away from exposure to the elements.

What they left behind for future generations was buried in the earth.

Paved Paradise

You don’t have to be an Indiana Jones fan to enjoy the park. You can do things that have nothing to do with archaeology.

Just ask Sandra Friend, who, along with her husband, operates the “Florida Hikes!” website. She said the park and its walking paths—one of which is 7 miles long—are “one of the places we consider ‘don’t-miss.’” Anglers can catch either saltwater or freshwater fish, because the park sits on the edge of an expansive coastal marsh, as well as the Crystal River. The park is part of the Great Florida Birding Trail, so it offers birdwatchers the chance to observe a variety of species. It’s popular with people who are into geocaching, too. For avid walkers, there are lots of hiking trails. It’s even a nice place to dine outdoors.

“There are picnic tables right on the river,” Hofelt said.

But by far the biggest reason to visit is to see—and to scale—the most impressive mound, the one known as Temple Mound A. Its summit is the highest point in Citrus County, Hofelt said.

Its great height made it “a symbol of grandeur that would impress visitors,” notes a display at the park. The mound was made of more than 300,000 cubic feet of shells, which should give you some idea of how much seafood the inhabitants consumed. Scientists estimate that it took them nearly 20 years to build the mound.

Originally, the high mound was 30 feet tall, 182 feet long and 100 feet wide at the base, with an 80-foot-long ramp to the top. Unfortunately, after the mound stood proudly intact for 10 centuries, one of the clueless 20th-century owners of the site excavated two-thirds of Mound A.

Pluckhahn said some of the shells were used for road building, but by the early 1960s, the owner had used some of the mound’s contents as fill. They put it in the marshy area to the east to build a dry base for development of a mobile home park. Feel free to roll your eyes at the thought of putting in a mobile home park on such a prestigious site with such a rich history. Park officials and scientists protested the damage, but the owner told the Ocala newspaper he had “every right in the world to act as he did.”

But wait, it gets worse.

“A tall fence obstructed part of the mound,” Pluckhahn said. “The family that owned it had plans to build an even bigger mobile home park, one with a marina.” They wanted to dredge the river for a deeper swimming area and even turn the top of the mound into a shaded patio-like resting place for residents.

But when the “Storm of the Century” hit in 1993, it virtually demolished the mobile home park, he said. There was little left but the concrete pads the mobile homes sat on. The state bought the 7-acre parcel in 1997 to add to the park and finally tore down the fence.

Despite the loss of some of its height, the amount of Temple Mound A that remains will wow anyone used to perpetually flat Florida. From such an elevated vantage point, visitors can see for miles. You can also gaze down on the same tidal creek that provided the original inhabitants with all those shells and watch the boat traffic on Crystal River. The eminent Florida archaeologist Jerald T. Milanich called the view from here one of his favorites.

For the original inhabitants, the mound provided a lookout point from which they could keep watch for intruders. But Temple Mound A probably had a more ritualistic purpose.

“Picture a ceremony held atop this mound, with the people on the ground below watching, in awe of the story being told,” the park’s website said. “Think about the possibility of a large structure on this mound serving as a meeting hall for the local leaders. Envision how this imposing structure would have filled the inhabitants with pride at the power and wealth of their society.”

Today, of course, there’s no structure up top, other than a large wooden platform and a couple of benches for the folks who become worn out from climbing all those steps. But there’s no obstruction to viewing everything below, with 360 degrees of visibility.

The mound still has some ceremonial uses. The park advertises that couples can rent out the top of Temple Mound A for weddings. “The temple mound platform has seating for 10,” the website notes, “but has enough standing room for 20.”

Curious Gopher

Several of the other mounds in the park were used for burials. Those were the ones that most interested the first 20th-century visitor, Clarence B. Moore, to explore the site.

Moore was a wealthy amateur archaeologist from Philadelphia. He had his own steamboat, which he used for venturing along the rivers of the South looking for undiscovered archaeological treasures.

“It was named The Gopher because he used it to go dig stuff up,” explained Nancy White, a USF anthropologist who has written extensively on both Moore and Florida’s mounds and middens. “He wanted beautiful artifacts, as well as information about past ways of life, so he went to Sopchoppy and hired a crew of Black men. They would … do the digging for him.”

Moore first showed up in Crystal River in 1903 to dig for clues to Florida’s past, then returned twice more because he found it such a rich location for his work. He mapped the entire site. It was his idea to designate each mound with a letter, the system still in use today.

“Moore mapped the relative distances and orientations of these mounds with astonishing accuracy, given the simple mapping technology of the day, as well as the dense vegetation that covered the site at the time of his visit,” a scientific paper co-written by Pluckhahn notes.

Because Temple Mound A contained nothing but shells, he didn’t spend much time on it. Instead, he focused on the places more likely to hold unusual items from the bygone civilization. His crew’s excavations of the burial mounds produced the artifacts for which the Crystal River site would become well-known among archaeologists.

“Textbooks frequently mentioned this site when they were published in the ’50s,’” Pluckhahn said. Moore, on the other hand, does not enjoy such a stellar modern reputation.

“Some people think he was just a looter because his methods were different from the ones we use today,” White said.

That is a common complaint about early archaeologists, she said, but Moore deserves to be held in higher esteem. She explained: “The difference between him and the other amateur archaeologists of the day is that Moore published his results.”

He took careful notes on where his crew went and what they found there, White said. His notebooks are a treasure trove for modern scholars.

Moore excavated a copper panpipe and shell ornaments, one in the shape of a flower with petals. The copper and meteoric iron ornaments he found were strikingly similar to ones found in the Ohio River Valley, showing the extent of the trade among these ancient civilizations.

He also found a panther jaw and the modified teeth of bears and other carnivores. Those may be parts of masks used in religious ceremonies.

Set in Stone

Three Citrus County families donated the Crystal River mounds to the state in 1962. During the work preparing it to become a park, archaeologists discovered two limestone monuments just 75 yards east of the main burial complex.

These stones were believed by archaeologist Ripley P. Bullen to be “stelae,” which are carved or inscribed stone slabs or pillars used by ancient peoples for commemorative purposes. Bullen believed the first stele was a ceremonial stone, one purposely erected for ceremonial and celestial purposes.

One of them carries an image of a human carved into it. Bullen believed that the human form was of great significance. He contended it was like other carved stones found at pre-Columbian sites in Mexico, Central America and South America. But modern archaeologists are quick to point out that there’s no evidence of a connection between the two far-flung cultures.

Further explorations of the first stone uncovered stone chips and food remains near it, which suggest that offerings were left there for the dead. The other stone seems more mysterious in purpose. It was clearly shaped by human tools and set upright, but its purpose remains obscure.

“We can only guess at its uses and significance to the people who formed it,” the park’s website says. “These pieces of rock offer us a rare and exciting insight into some of Florida’s first peoples.”

Since then, a third possible stele has turned up as well.

Calculations by modern archaeologists have found that these stone markers may have been used to record the position of the rising sun at the winter solstice.

A Glimpse Into the Past

Most of Moore’s discoveries went to a museum in Philadelphia for display. Eventually, the museum decided to sell off Moore’s artifacts, White said. They wound up in the possession of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian, but they’re no longer on display to the public, she said.

After the state took control of the Crystal River property, someone in charge came up with the bright idea of creating a way to walk through one of the burial mounds.

While passing through, you could look through a clear window at the remaining skeletons Moore had left untouched, White said. The interest in the education of the public overrode any concern about good taste or cultural sensitivity. Native Americans complained about how offensive that was, so the state eliminated that feature of the park, she said.

His methods were different from the ones we use today.

—Nancy White

A much better educational feature constructed at the park is the Crystal River Archaeological Museum, opened to the public in 1965. Designed by architects David Reaves and Dan Branch of Gainesville, the museum is considered a historically significant example of midcentury modern architecture. The state park website says the design’s “attention to detail in the look and layout combined practicality with visions of majesty … Look closely and you may be able to imagine how the design mimics the flat-topped temple mound features at the site.” Plus, it notes, “the design incorporated floor-to-ceiling windows, optimizing the use of natural light inside of the structure while allowing guests to experience unobstructed views of the surrounding landscape.”

It was built before air conditioning was a standard feature of Florida construction, so it was positioned to capture the breezes that track the contour of Crystal River. The building sits on a base of sand, with the additional elevation preserving the museum from river flooding events during major storms.

Allow yourself plenty of time to tour the museum, because in addition to the exhibits, there’s a room where visitors can see a film about the park and its significance. The museum offers visitors a comprehensive education in what’s been found at the park and who found it. However, some of the items it held when it first opened are no longer there for visitors to enjoy.

In 2005, someone stole more than a dozen arrowheads and a ceremonial knife from the museum. The thief or thieves broke in through a side door and didn’t touch any other items in the nine exhibit areas.

“They knew what they were after,” the park manager at the time told reporters.

The break-in led to a decision to use as many replicas as possible in the displays, instead of the real artifacts unearthed by Moore and others.

It’s the one phony element of this authentic treasure.