by Carrie Honaker | June 20, 2024

Stilt Houses and Scallops: A Dive Into Old Florida’s Hidden Gems

A writer rediscovers her love of scalloping amid the historic stilt houses in New Port Richey, Florida.

The sun rises on a steamy July morning as I sip my coffee and slather sunscreen all over, preparing for a day out on the water hunting for culinary treasures and reconnecting with a dwindling Old Florida pastime I loved as a college co-ed 25 years ago. Back then, the waters and grasses of Florida’s Gulf Coast were plentiful and deceivingly clear. I wonder if, like many things from that era, it’s not quite the same.

I have a charter boat and captain waiting for me at the Sunset Landing Marina on Florida’s Sports Coast. I’m ready to dive in for my dinner. Sea trout, red drum, flounder, shallow water grouper, snook, cobia and tarpon are plentiful in these warm Gulf of Mexico waters, but I’m here for the tender, sweet bay scallops hiding amid the waving meadows of seagrass on the sandy bottom.

After a short safety briefing and allocation of masks, fins and snorkels, Captain Mark Dillingham deftly maneuvers the 23-foot Key West Bay Reef boat through New Port Richey’s Venice-like canal system, passing working fishermen, collections of eclectic homes and sporadic mangroves as he motors toward the scallop beds adjacent to Pasco County’s historic stilt houses.

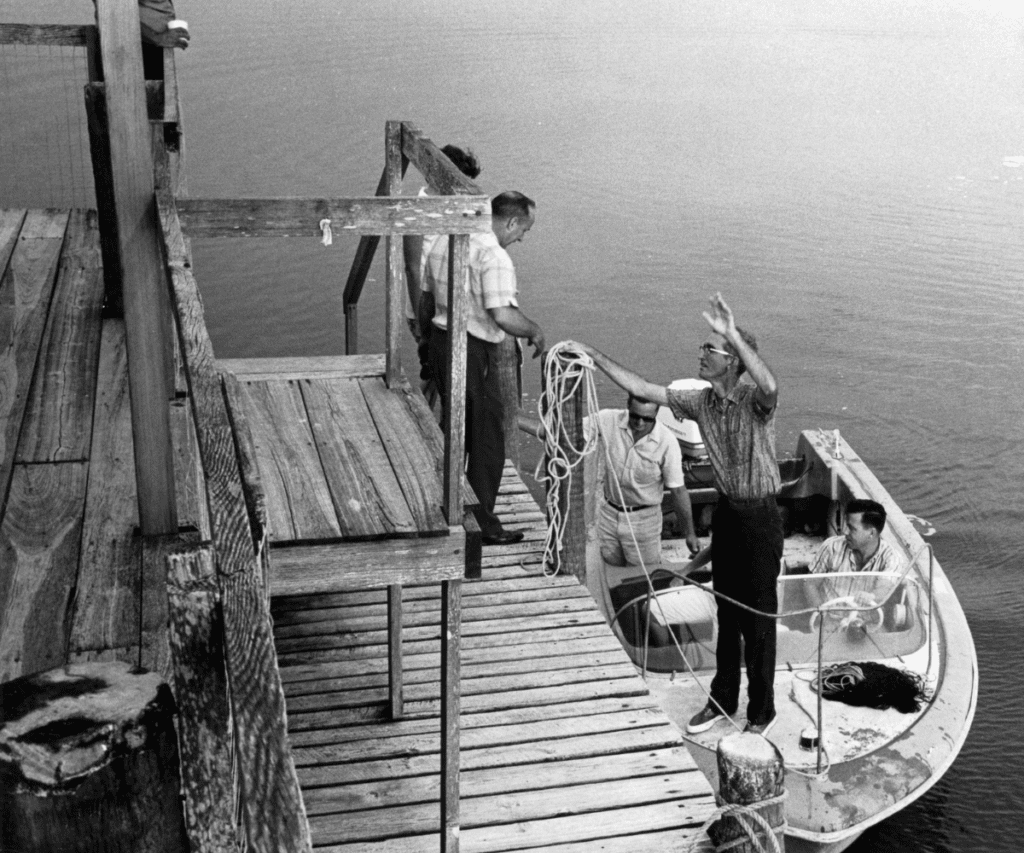

Rounding the corner from Durney Key, a primitive no-man’s-land island where locals tuck in for private picnics, nine wooden structures rise out of the water. These fish camps, erected as early as 1916 (though a specific date has not been verified), remain privately owned and once numbered 24 before natural disasters claimed some. They recall a slice of Old Florida before motorboats existed, when fishermen would push their boats with long poles. The elevated camps, much like shanties for ice fishing, gave them a bird’s-eye view of running fish, a covered spot to shelter during pop-up storms so common in Florida and a convenient place to store their catch.

Primitive Fishing Camps Find New Life

The stilt houses, as they are now known, sit four to six feet above shallow water and are anchored by pilings buried in the sandy bottom. In 1968, Hurricane Gladys ripped through Pasco County and decimated many of the fishing lodges. Some rebuilt, claiming squatter’s rights when the state ruled no new stilt houses could be erected. In 1989, stilt house owners and the state came to an agreement where the land beneath the houses could be leased from the state. The existing nine houses cannot be sold by state mandate, but families have handed them down through generations.

The Lake family moved from Pinellas County to Pasco County in 1974. Dave Lake ran for county commissioner and was a local contractor who built a lot of houses and buildings in the area. He bought two stilt houses but eventually sold one before the state mandate. According to his son Brian, who now owns the stilt house with his brother and their families, upkeep is the greatest challenge in the face of the longer hurricane season along the Gulf of Mexico.

Dillingham fills me in as we motor across the salt flats towards Green Key Beach, watching stingrays spread their diminutive wings and flutter across the water, “They didn’t have the type of boats that we have today, so commercial fishermen would stay at those camps, catch their fish and bring them into market whenever it was time for them to drop them off. There are a few places in Florida that still have houses on the water, but nothing like the line of houses you see when you go out of the Cotee River. Movie stars and singers used to use this area as a little hideaway to escape the media—June Carter Cash’s family owned a house on the river, and both June and Johnny spent a lot of time out on the stilt houses with friends back in the day.”

Tomás Monzón, the vice president of West Pasco Historical Society, added that the houses served a practical purpose to get fishermen closer to their catch, making fishing a more sustainable industry in the early days of Florida. “They could store their tarpon and mullet, and some of the houses have trapdoors in the main living area where they could fish from inside the house if it was cold or windy,” he said.

How to make Gill Dawg’s pan-seared scallops

Like the challenges faced by pioneers along the Oregon Trail, settlers in Florida braved a wild frontier filled with dangerous wildlife, poisonous plants and rugged conditions. Monzón added, “In the early 1900s, when the first stilt houses were erected, Florida was an undeveloped, wild state. It took courage to bring your family and settle here under tough conditions.”

The West Pasco Historical Society operates a small museum inside a former 1900s two-room schoolhouse in New Port Richey, where visitors can see images of original settlers showing off their 20-foot tarpon and crews of men in the water working on the stilt houses. “We have exhibits on each section of West Pasco County, including artifacts from New Port Richey’s era as the Hollywood of the East in the 1920s,” Monzón said. Silent movie star Thomas Meighan and golfer Gene Sarazen were the plank holders that led to Irving Berlin, Raymond Hitchcock, Leon Errol, Gloria Swanson, Ed Wynn, Charlie Chaplin and more flocking to the area. The Hacienda Hotel opened in 1927 and was ground zero for Hollywood literati, and the stilt houses became a popular hangout.

Diving In

Stilt houses in the distance, we anchor up at the scalloping beds and get ready to dive in. My body thrums with nervous energy as I fit on a pair of fins and try to adjust my mask over my humidity-plumped mass of curly hair. Dillingham hands me a mesh bag and gives instructions about finding the delicate bay scallops in the shallow 8- to 10-foot water. I confidently take the bag, assuring him I’m an experienced scalloper. Inside, I’m wilting with the very real possibility of failure. But, the clear water provides a perfect view of the green seagrass below, dotted with swathes of sandy bottom, and there’s nothing left to do but jump in and get to it. The bivalve mollusks have up to 100 pairs of tiny blue eyes along their shells, making them easy to spot among the waving blades of seagrass. Dillingham likens it to an underwater Easter egg hunt.

There’s something special about popping that shell open and scraping it down to uncover that tender piece of meat. —Mark Dillingham

Commonly known as bay scallops, Argopecten irradians like the shallow, nearshore waters along Florida’s Gulf Coast, from Port St. Joe down to the Florida Keys. The delicate balance of salinity in estuaries where freshwater rivers flow into the salty ocean yields the largest scallop populations. According to Erika Burgess, the section leader for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s (FWC) Division of Marine Fisheries Management, scallops play an important role in the local ecosystem, “removing phytoplankton, which helps their primary habitat, seagrass. Their shells form a habitat for many types of organisms, such as juvenile scallops (spat), crabs, worms, sponges, bryozoans and even benthic algae. Once the scallops die (either predation or natural death), the shells help stabilize the seagrass soil and also buffer the pH of sediment. They are an important food source for animals like crabs (including stone and blue crabs), as well as many types of fish.”

I got my first taste of scalloping in the early ’90s when the population still flourished along the Forgotten Coast (Franklin County), just a short drive from Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida. My college roommates and I loaded up our snorkeling gear, buckets and mesh bags and headed to St. George Island for the weekend with images of snacking on crisp tortilla chips loaded with fresh ceviche—the perfect beach meal. Dwindling scallop populations led to regulation, including prohibiting commercial harvest by 1994. Recreational harvests like mine still flourished, but parts of the state began to set up seasonal windows in response to changing scallop populations.

Reduced seasons, combined with restoration efforts, have allowed recreational harvest to continue along the Gulf Coast, but Burgess added, “Neither closure nor restoration have allowed reduced scallop populations from Tampa Bay southward to overcome the negative impacts of red tide, but specific harvest area limits and seasons appear to work in most areas on the Gulf Coast of Florida.”

The vulnerable mollusks need clear water and abundant seagrass to thrive. Like other bivalves, scallop spat attaches to the sturdy seagrass blades to grow into maturity. Unfortunately, the warming Florida waters threaten developing scallops. Higher temperatures inhibit seagrass growth, leaving less habitat for the scallops, and the warmer the water the less oxygen available when the species needs it most. But Burgess and her colleagues at FWC keep close tabs on population health. 2018 marked the first year recreational scalloping returned to Pasco County—24 years after a pause due to declining scallop numbers. This year’s 40-day scallop season in Pasco County (July 10 – Aug. 18) signals the longest since scalloping returned to the area.

Armed with Dillingham’s advice about bay scallops’ ability to swim backward and quickly pivot from predators, I dove in, hunting for the 3-inch bivalves for the first time in more than two decades. Amid meadows of eel and turtle seagrass beds, spotting their mottled upper shells proves difficult. I move to the sandy bottom areas where the seagrasses join and spot my first set of electric blue eyes. Moving quickly is key, as scallops generate thrust with the opening and closing of their shells, propelling them away from danger. I quickly scoop up my catch, being careful of my fingers as it snaps its shell shut, and deposit it into the mesh bag.

Seasoned in the ways of scalloping once again, I quickly fill my two-gallon limit without a finger snap incident. Each person is allowed to harvest two gallons unshucked or one pint cleaned, with a total of 10 gallons per boat.

Hand-harvesting scallops while snorkeling the clear Gulf waters is a nostalgic pastime for many Florida families, including Dillingham’s. “I’ve been raised almost my entire life right here in Pasco County. My dad was in the shrimping industry, and I remember as a kid sitting in a beach house cleaning and shucking tons and tons of scallops right on the Cotee River. But then overharvesting on the commercial side wiped out the population, and the state closed the beds. I was happily surprised when they found the population was back,” he said.

Commercial scalloping remains closed, but recreational scallopers like me can snorkel or freedive for them with a Florida saltwater fishing license or book a trip with a licensed captain like Dillingham.

Hook and Cook

Back on the boat, Dillingham maneuvers us in the shadow of the iconic Lake family stilt house. Paddleboarders and kayakers meander around the American flag-emblazoned structure that lightning struck in 2018 and burned to the pilings. The Lake family was able to rebuild because the stilts were still standing in the water. In thinking about the history of the stilt house, Lake added, “It’s a piece of Pasco history, and my dad worked real hard to get us the approval to build it in 2002. He sat in front of the Governor’s whole cabinet and the Department of Environmental Protection. Once he secured it, over 100 people helped us rebuild, and my dad collected all the names. He passed a couple of years ago, so keeping it within the family means a lot.”

The Lakes had different versions of an American flag on their stilt house through the years, but the current depiction was painted after the fire in 2018. Lake added, “We built it in 2002, and then 16 years later, we had to rebuild—it just took the wind out of our sails, but with help from friends and a lot of personal labor, we rebuilt everything ourselves in four months. The last touch was my wife and family going out and hand-painting the American flag mural you see today.” The Lakes often spend weekends hanging out at their stilt house, where their father’s legacy echoes in the timber surrounding them.

In the early 1900s, when the first stilt houses were erected, Florida was an undeveloped, wild state. It took courage to bring your family and settle here under tough conditions. —Tomás Monzón

Dillingham retrieves a scallop from our communal ice chest—chilling them is the key to getting the shells to open—and pulls out his trusty spoon to demonstrate how to shuck a scallop, a skill in all my years of working in and around restaurants I have never mastered.

He started using the spoon method after years of cleaning scallops with a knife. Frustrated with manipulating the sharp knife tip around the shell to scrape it clean, he purchased spoons and ground the tips so they had a sharp point like the knife but a shape that mirrored the scallop shells. “Some of the scallops are stubborn, even after icing them, but the spoon helps me get in the corner of the shell and lift it to where that muscle separates. The spoon fits the shell, so it just rolls right around the meat. You clean the top off, pull it down and separate the top part of the shell, and then as you hold it away from you, you just scrape everything else off around the meat in one movement. It’s best to do it over the water so everything just goes back into the ocean, including the shell once you get your scallop free,” he said.

After a few tries, I catch on to the spoon method and make quick work of my two gallons, reserving a couple of shells to clean and add to my collection at home and one unshucked for the ride back. After everybody’s finished shucking, Dillingham points the pontoon toward Gill Dawg Tiki Bar and Grill, where we will drop-off our bounty to be prepared in their “Hook and Cook” program.

We called ahead as Dillingham suggested so Gill Dawg knew we would be bringing our catch for them to cook for dinner later that evening. The sprawling complex captures Old Florida, with memorabilia like vintage surfboards, old gas station signs and a mural of classic Florida scenes that stretches around the rafters of the dining area. There is a main restaurant, patio, multiple bars, three musical stages, a marina and a dive shop. Waterside tables dot the shore where you just caught your dinner while a musician strums a guitar, serenading the sunset as you enjoy the fruits of your labor.

They blacken, grill or fry the catch and serve it with two sides. Hayley Jackson, Gill Dawg’s general manager, added, “As long as the tide is right, you can boat right up to drop off your catch. You choose how you want it cooked, and we take the dirty work out of dinner. We have fries, coleslaw, an awesome veggie mix, sweet potato fries, onion rings or our cilantro lime rice as side options.”

“When you catch your dinner, you don’t go to a restaurant and wonder how it got here. You swim and collect the scallops. There’s something special about popping that shell open and scraping it down to uncover that tender piece of meat. It’s so sweet just right there raw out of the shell,” Dillingham said. He added, “And for me, it’s the smile on a person’s face after I show them something (like scalloping) that they’ve never experienced before that keeps me taking my boat out every day. Whether we’re out here for 10 minutes or four hours, swimming in the crystal clear, warm water hunting for scallops with family and friends is something many people don’t realize they can do.”

Motoring back to the marina, I spy a pod of dolphins frolicking in the ocean. This area draws gentle manatees, small bonnethead sharks and a bevy of birds who love the mangrove shorelines and shallow grass flats. Pelicans swoop down to grab their dinner out of the waters I just snared mine from, a bald eagle perches in a spindly mangrove outgrowth and a majestic blue heron glides across the surface of the untouched water to my left as we pull in beside the Hacienda Hotel to tie up and disembark.

“We have one of the prettiest grass flats in the entire state right here in Pasco County. We have so much clean water, and I’ve fished in numerous parts of the state, but the estuary here is prettier to me. We have a lot of freshwater springs that bubble up inside of some of these canals along the whole coast of Pasco County. That’s something special you don’t find in many places across Florida,” Dillingham said.

In those hours feeling my way through the seagrass in the shadows of the stilt houses, I waxed nostalgic over that treasured but fleeting Old Florida pastime, but each time I crested the water’s surface to come up for air or check my bounty, I gained a new appreciation for the current fragility of the seagrass meadows and the delicate balance of the larger ecosystem surrounding bay scallop populations. As the sun descends and the sky turns to fire, I pop open my last scallop, saved for the boat trip back. I deftly move my spoon around the shell, cleaning it with one movement like Dillingham taught me, and slip the tender jewel of meat into my mouth—one last taste of Pasco County, raw and unfiltered. The sweetness brings me right back to those early days wading out into the waters of St. George Island and discovering the wonders of the world underneath.