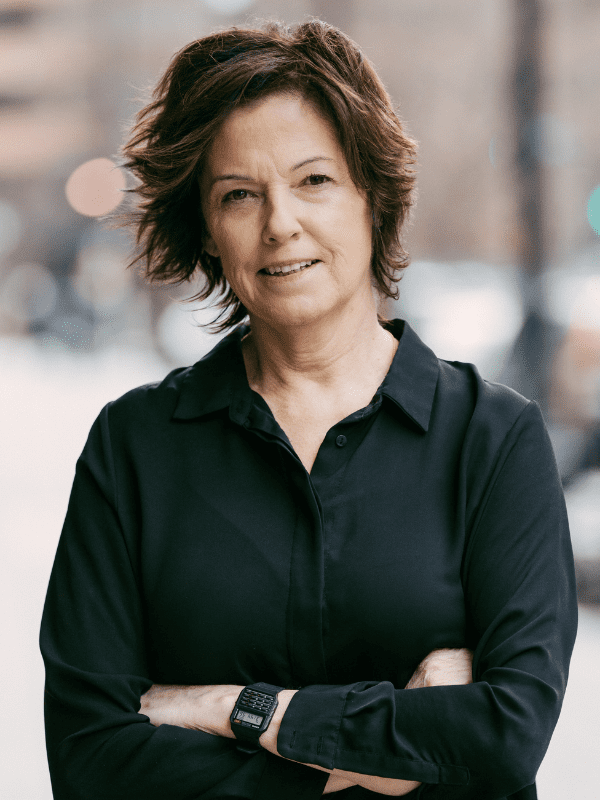

by Anne Hull | March 28, 2024

Through the Groves With Author Anne Hull

An excerpt from author and Pulitzer Prize-winner Anne Hull’s memoir depicting her coming of age and coming out in Central Florida.

A dirt road took us there. When we reached the grove, the Ford hesitated, as if sizing up the chances of a square metal machine penetrating the round world of oranges.

“Hold on, sister,” my father said, shifting gear.

His CB radio antenna whipped in the air like a 9-foot machete. It caught in the tree branches and bent backward, then THWACK. Leaves and busted twigs rained down on us inside the car. Pesticide dust exploded off the trees. And oranges—big heavy oranges—dropped through the windows like bombs.

“Look out for Bouncing Betties!” Dad yelled when one hit the front seat.

Slats of raw sunlight bore down through the shade of the trees as the dirty beige Ford moved through the flickering movie. My father studied each tree we rolled past, glaring at it with suspicion, looking for all the ways it might be trying to trick him.

It was the summer of 1967 and he had just started his new job as a fruit buyer for HP Hood, the juice processor. He was supposed to make sure Hood got the best quality oranges and grapefruit for juice production. After he bought the citrus from growers, he had to keep the trees healthy until the fruit was ready to be picked, and then he had to ensure that the truckloads of citrus arrived at Hood’s juice house on time.

“The variables out to defeat a man are many,” my father said, exhaling smoke. “Bugs, drought, freezes, aphids, red mites, canker, labor problems.”

Sweat trickled down the side of his face as he brooded. He was 6 feet and lanky, loose-limbed, with one hand draped over the steering wheel and perspiration coming through his white Oxford shirt.

“How old are you, anyway?” I asked. I had just turned 6.

“Your old daddy is 28,” he said.

His attention was out his window, on the Valencia orange trees.

Valencias were juicers and soon to be in cartons in grocery stores if the variables didn’t defeat Hood’s new man in the field. We crept along at 3 mph. All of a sudden, he hit the brakes.

“Stay in the car,” he said, stalking off with his magnifying glass. I kept an eye on him as I unwrapped the bacon sandwich my mother made for me. He held his magnifying glass over some leaves, Sherlock Holmes–style.

A bathroom! Of all the misinformed advice. So far that day, the closest I saw to a bathroom was a tar paper shack next to an irrigation ditch. When I had to go, Dad reached under his seat for a roll of toilet paper. “Take this,” he said. Two rows over, I squatted in the sand, holding a stick for snake protection.

My mother had given me lots of instruction. Don’t talk too much. Don’t pester the man with questions. Drink plenty of water. Speak up if I need to use the bathroom.

“Best not to shatter all your mama’s illusions by telling her every detail,” Dad said when I got back in the car.

I’d noticed the box of test tubes rattling on his back seat. I asked him why he needed test tubes with stoppers. He said Hood required him to test juice samples for sugars and acids.

I could see the test tubes were unused. None of the seals were broken. That didn’t seem right. “Are you going to get in trouble for not testing the juice?” I asked.

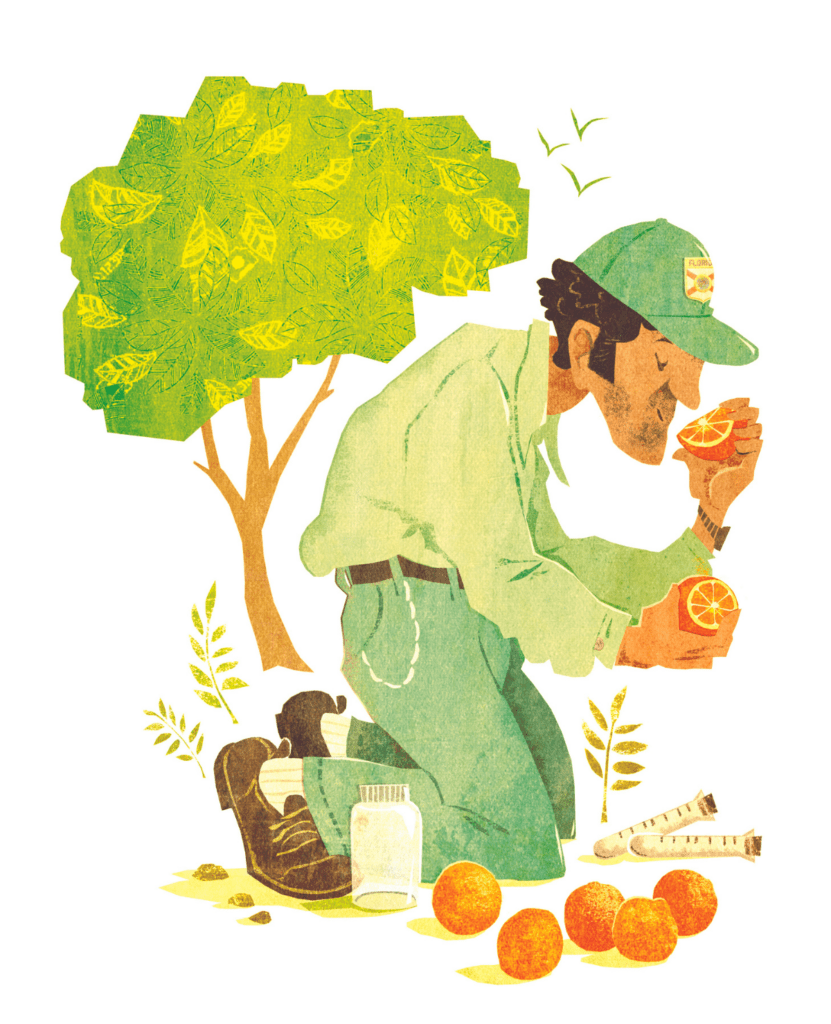

He said he preferred what he called the old-fashioned taste test. I would watch him do it a hundred times that summer.

He stood by a tree with his pocket knife, cut a hole into the orange and sucked the juice out. He held it in his mouth for a few seconds, calculating the juice into yields, pallets and truckloads, then spat into the dirt. He had his answers.

My father studied each tree we rolled past, glaring at it with suspicion, looking for all the ways it might be trying to trick him.

—Anne Hull

My father’s territory was the citrus-growing region of Central Florida known as the Ridge. It ran a hundred miles from north to south, from up around Clermont straight down to Lake Placid. It wasn’t a large area, but in the 1960s the Ridge had the heaviest concentration of citrus groves in the world. One botanical grid after another, dark green regiments of trees marching up and down the middle of the state. We lived at the bottom of the Ridge in a town called Sebring.

In spring, when the orange blossoms opened, it was like God had knocked over a bottle of Ladies of Gardenia. The smell was so strong it burned into my hair and clothes, and the dog’s fur. The blossoms heaved and sighed for three weeks straight, and just as they started to fade, the cooking houses started processing fruit for juice. For 10 hours a day, the cook houses pumped caramelized smoke into the air that smelled of spun brown sugar.

Once, we’d gone to Jacksonville, three hours north of the Ridge, a paper mill town on the St. Johns River. When that rotten-egg breeze came rolling off the river, it left me gasping in the back seat, dazed by the realization that the world could stink. I was glad we weren’t in paper. I was glad we were in oranges.

If the history of Central Florida were charted out on a graph, it would start with primordial sludge and then curve toward the Paleo-Indians, the Calusa Indians, the Tocobaga Indians, Ponce de León, runaway slaves, snuff-dipping white settlers, the U.S. Army, Osceola, the great Seminole warrior, malaria, cattle, citrus and a dull heat that left it undesirable for much besides oranges until the early 1960s, when Walt Disney took a plane ride over the vast emptiness, looked down, and said, “There.”

The interior of Central Florida was so desolate that my father kept a gallon of water and a box of Saltines in his car.

He said you could eat all the oranges you wanted, but good luck if you needed a flush toilet or a pay phone. He also said it was no place for a child, though Disney was betting otherwise.

Florida’s other citrus-growing region was much smaller, east of the Ridge, along the coast, and it was called Indian River.

The Indian River people did a better job marketing their fruit, rhapsodizing about tidal Indian breezes that rang like poetry in the Yankee ear. Their fruit was prettier to look at because each piece of fruit was buffed out to the shine of a Cadillac. On the Ridge, we didn’t mind if an orange left your hands dirty as long as juice dripped down your chin. Plus, we had more groves, wall-to-wall.

The competition was from California, though it was hardly a contest. The unremitting heat and humidity on the Ridge made our citrus exceptional juice bombs.

What had started to pose a threat was a variety coming out of California called the seedless clementine. It was a no-fuss version of the Florida tangerine, which was loaded with seeds. Dad said it might ruin us for good.