by Eric Barton | March 25, 2024

Filipina Chef Nicole Ponseca Is Embracing Her Roots and Breaking Boundaries in Miami

New York restaurant darling Nicole Ponseca left the city and her culinary career behind. Now, the Filipina chef is surprising palates in South Florida.

Nicole Ponseca walks in looking very much like a rock star, wearing an oversized army surplus jacket cinched at the waist with a belt and a pair of oversized sunglasses. Every single employee in the restaurant knows her. They hug, exchanging air kisses, hellos and miss yous.

What an entrance. Like Ponseca, the restaurant, Pastis, is an expatriate from New York. Like Ponseca, it’s glamorous, a French bistro in the middle of Miami’s trendy Wynwood neighborhood. It’s the hottest thing at the moment.

Ponseca joins me at a courtyard table, and I ask how everybody knows her. She looks nervous. “I have a secret,” she says.

Ponseca was, and maybe we should say still is, a celebrity chef. She’s never had a TV show or a documentary film crew following her around. Instead, she became famous for running two successful Filipino restaurants in New York City, writing an acclaimed cookbook and attempting to make Filipino food as popular as any other. Recently, she stepped off that track. You could say she blew up her life. She moved to Miami … and then there’s that secret.

Ponseca grew up a military brat in San Diego. Her parents emigrated from the Philippines and her father became a cook in the Navy. He’d be deployed for months at a time, and when he’d come back, Ponseca would glue herself to him, watching him shave or tag along on errands, anything just to be close. Often, they’d cook together. Not just three meals a day but they’d also create elaborate snacks, too. Ponseca liked to indulge in a steak sandwich with bacon and horseradish mayonnaise on a baguette. She’d have that at 3 in the afternoon most days. “Our together time was so valued to me,” she says.

Then came the teenage years, and Ponseca remembers pleading with her father to just be normal. Like most Filipinos, her father would eat with his hands, bringing a bowl just below his chin to scoop up rice with his cupped fingers. When her friends would come over, she’d beg him to order pizza or fried chicken, “anything that made sense” to be eaten by hand. She hated the idea that her American friends at school would think she was different. “The way to process that was to cover it up, shame, dismiss it, disassociate,” she says.

I would think, ‘Are white people going to like it?’ It was little microaggressions against myself.

— Nicole Ponseca

After receiving a business management degree from the University of San Francisco, she dreamed of working on Madison Avenue. She had $75 when she got to the city in 1998, living at first in a room in a Harlem convent, just her and the nuns.

Ponseca spent nine years in advertising, even rising to a VP position, all the while knowing that it wasn’t right for her. What drove that home was realizing the underlying racism that existed in ads: white models for the mainstream publications, Black models for the Black publications—and Asian models in none of them. “I would lie in bed at night listening to Mariah Carey, bawling my eyes out and knowing I was supposed to be doing something with purpose,” she says.

Wondering if that something else was the restaurant industry, she took a job at night washing dishes. By day, she was an advertising exec. By night, she was scraping pots. She quit advertising in 2007 and, figuring she had found her new career, took a job as a restaurant GM at Juliette in Brooklyn.

Try a bite of Nicole Ponseca’s Kinilaw na Hipon.

About then, she started to think about how Filipino food is underrepresented in America, even in the melting pot of New York City. Ponseca knew that the dishes were approachable, deeply flavored, ideal for the same mass appeal as say Chinese or Indian. Perhaps the best example of that is the country’s unofficial dish of adobo: chicken and pork reverse seared in a sauce consisting of soy, jam and garlic (her take). And yet Ponseca would notice how Filipino restaurants in America so often failed. She started taking stock of them, keeping notebooks filled with observations of why: lame ambience, most often, or failing to help newcomers understand the cuisine. For the next four years, her days off were spent testing Filipino recipes. And crafting a plan.

At first, she considered dumbing down recipes to appeal to a wider audience. “I would think, ‘Are white people going to like it?’ It was little microaggressions against myself,” she says. Instead, she decided that her place would be traditional, right down to serving balut, a Filipino dish consisting of a fertilized bird egg that’s partially developed. A challenge for Westerners? Yeah, and she embraced it.

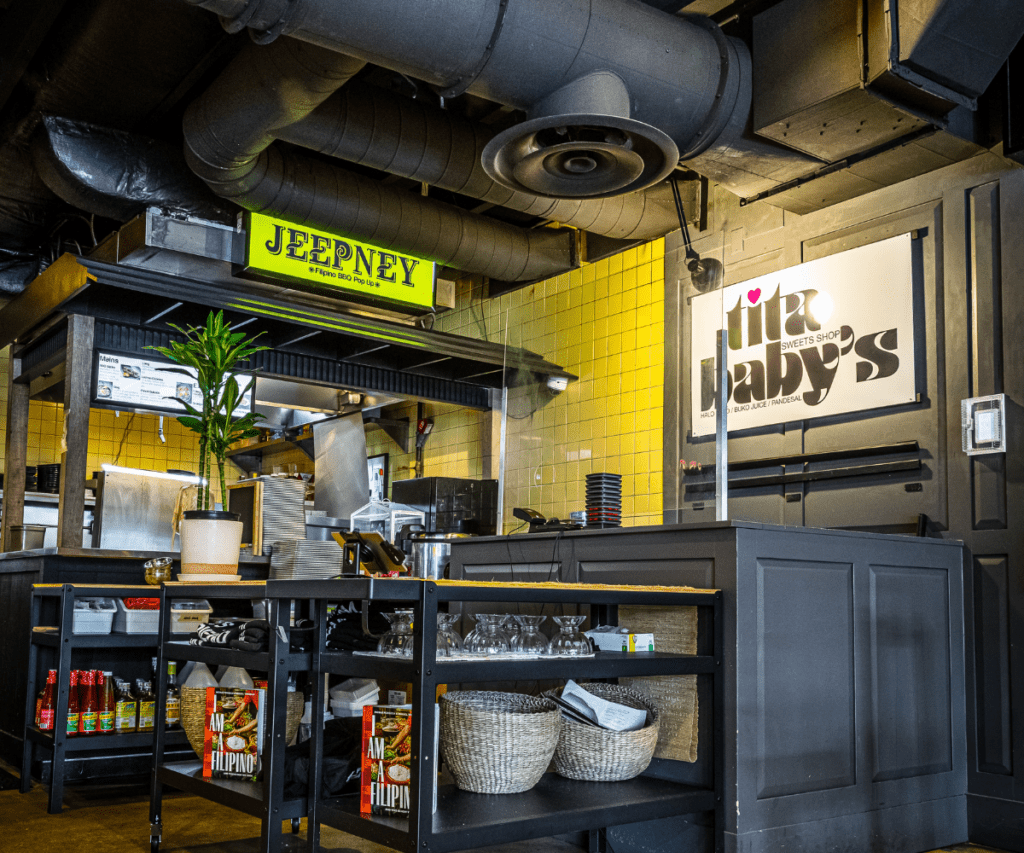

It started as a pop-up in 2011 with Maharlika, and by the third weekend, she had three-hour waits for a table. Nine months later, she added a second restaurant, Jeepney, and then a fast-casual Filipino noodles and barbecue concept called Tita Baby’s Panciteria, in Brooklyn.

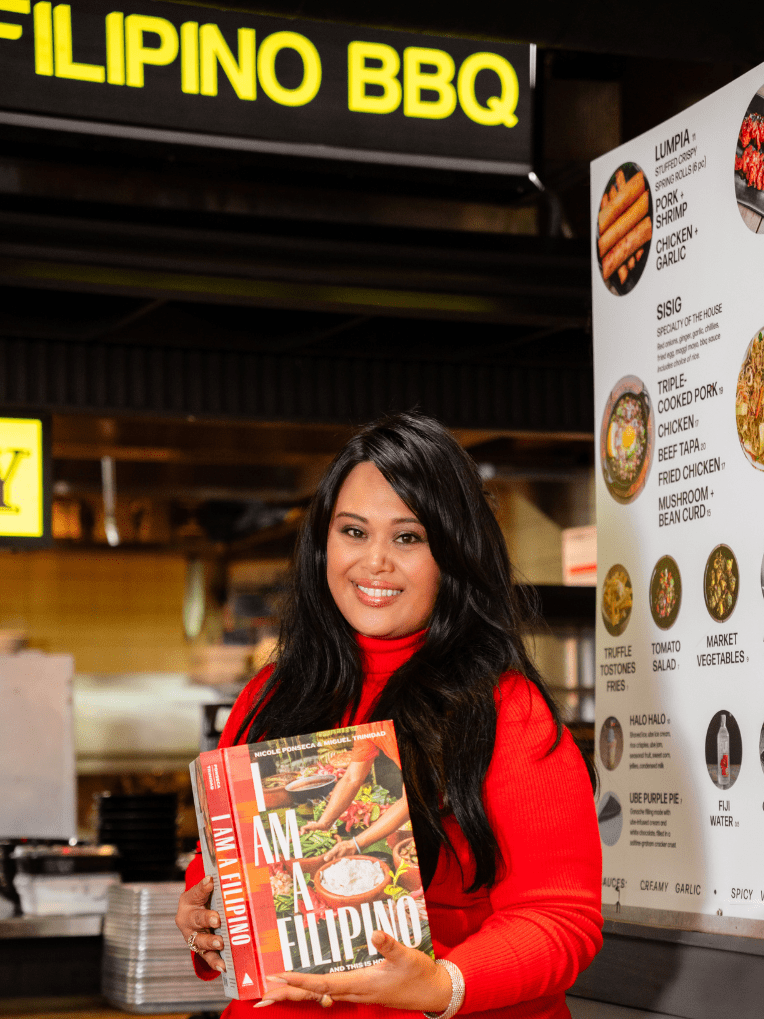

At Jeepney, her employees would yell “Balut!” any time someone ordered one, which was often. She called it Jeepney after the colorful repurposed army jeeps used as public transport in the Philippines. Reservations soon filled up months in advance. Fame followed, with articles in The New York Times and Washington Post. And she co-wrote a book, “I Am a Filipino: And This Is How We Cook,” which was a 2019 James Beard Award finalist.

It all lasted 10 years. Then there was a moment, as she struggled through COVID-19 restrictions, when she realized running a restaurant these days is about building an online persona, about pleasing DoorDash, about dishes being Instagram-worthy, about everything but cooking. She says, “I didn’t want to follow rules that I didn’t make.”

She walked away from it all in 2021, eventually closing her New York restaurants and renting an apartment in Wynwood. She ended up opening a Jeepney stall in the 1-800-Lucky food hall as a starting point for her new city. Then she got a call. Her dad was being rushed to the hospital. He couldn’t breathe. It was COVID. He was 77.

Ponseca called the food hall and said she’d need a couple of days to mourn. She says, “Hello! A couple of days? I had never mourned before. I had no idea. I was on the floor sobbing.” She found someone to run the food hall stand for a year while she figured out what was next. And then comes the secret life she’s been living.

Wondering if she was still interested in the restaurant industry, she applied for a job at Pastis. Not as a chef, not as a GM, but as the receptionist, handling phone calls for hard-to-get reservations. Nobody knew who she was, this famous restaurant owner and author from New York. In the hierarchy of the restaurant, she was now at the bottom—until a coworker recognized her one day. He brought in a copy of her book and asked her to sign it. One of the managers asked incredulously, “Who are you?”

By then, nine months into her undercover life as a receptionist, Ponseca had already been thinking about getting back on track. She quit Pastis and took back her food hall spot. At that point, Jeepney was just limping along.

She spent months working on the recipes, adding and subtracting things and making sure her staff was explaining the dishes to people who’d never had Filipino food. She’d stop by tables and offer to refund anything they didn’t like and replace it with something else. She brought in a new management team and hired a crew to help scale it up. The day we met, about a year since taking it back over, she had solidly turned the business around. These days, she’s looking for what’s next. It’ll be Filipino. Traditional but also casual and fun. Maybe the first of many. Maybe the start of putting one everywhere, of finally making Filipino food famous.

First, she’ll be doing a series of kamayan pop-up dinners around Miami, served family style on banana leaves. There will be no silverware. Like Ponseca’s father, everyone will be eating with their hands.

Overall, though, she’s looking for how she can influence everything—and she doesn’t mean the internet. Ponseca says, “I know there’s something out there for me to capsize. As a woman, an entrepreneur and a person of color. That’s. Fucking. Dope.”