by Diane Roberts | June 13, 2023

Why is “Free” Florida Banning So Many Books?

Diane Roberts reminisces on the palace of her youth, FSU’s Strozier Library, and why books have been banned throughout history.

I used to live in a palace. Not the kind you’re thinking of, with rooms of gilt carvings, silk carpets, chandeliers and doors of faceted glass leading to more rooms with secrets and wonders. My palace was the nearly deserted fifth floor of the Robert Manning Strozier Library, where the old Dewey Decimal System books, the ones not yet given their Library of Congress numbers, sat higgledy-piggledy on metal shelves, unloved and largely untouched. There were newer, nicer editions downstairs, but I preferred these scruffy old volumes. In the seventh grade, this place was my refuge and my treasure house. The ceramics class my mother taught three days a week didn’t finish until 5 p.m., so I’d walk from my school on the western edge of the Florida State University campus to the library to wallow in words till she could come pick me up. Sitting on the linoleum floor, fortified by smuggled Lance Nip Chee crackers, I’d pull out book after book, entering the halls of the Aesir, the drawing room at Mansfield Park, the bedroom where Emma Bovary lies dying, a dark wood outside Florence, the yard at a Virginia plantation where a woman is being whipped. I read promiscuously, barging into unknown worlds, wandering down dark corridors, always happening on the unexpected, the weird, the glorious, the heartbreaking, the hilarious. No window or door in what Henry James called “the house of fiction” was ever locked. No book was ever forbidden.

I was lucky, growing up when I did, in a home full of books, all of which I was encouraged to read. I went to a school where the library did not restrict what I could check out. I remember reading The Eve of St. Agnes, a poem about a young nobleman sneaking into his love’s bedroom at night, in seventh grade. Much of it was beyond me. I got the parts about food, those candied apples and jellies and cinnamon syrup; I missed the parts about sex. Happily, my English teacher was allowed to talk to me about John Keats’ gilded eroticism. Apparently, I wasn’t permanently scarred by reading “Ethereal, flush’d, and like a throbbing star/Seen mid the sapphire heaven’s deep repose;/Into her dream he melted … ”

Stories That Scandalize

These days Florida’s education authorities work feverishly to ban books from schools and libraries and classes as if what’s inside will destroy the moral character of anyone who encounters them. Teachers are so scared of being fired or even arrested, they’re taking books off classroom shelves. Librarians are subjected to “retraining” on what books the state might deem objectionable. That’s hundreds of books in some districts, books about Pocahontas, former President Barack Obama and Rosa Parks, books about being raised by two mothers, books about Latina grannies and Chinese railroad builders. In Duval County, an “instructional materials” supervisor decided teenagers must not be allowed near The Best Man by Richard Peck: apparently a happy scene of two men getting married undermines the American way of life. Orange County has “removed” two books (Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe and Juno Dawson’s This Book Is Gay) which discuss sexuality; Flagler County doesn’t allow school libraries to offer Jesse Andrews’ novel Me and Earl and the Dying Girl (sex and “bad language”) and 13 Reasons Why by Jay Asher (drugs, booze and suicide). An outfit called Florida Citizens Alliance wants to deep-six a slew of books it finds unpalatable, including Judy Blume’s Forever and Angie Thomas’ young adult novel The Hate U Give, which explores how a smart young girl struggles to deal with the death of her friend at the hands of the police. A little too militant for Florida schools, I guess; a little too Black Lives Matter. The so-called Moms for Liberty and their acolytes have called The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, “pornographic.” A woman who appeared before the Hillsborough County school board hadn’t read the novel, but she confidently asserted that it was too shocking and dirty for even advanced students to read. She knew this because a “review” of it mentioned “every single different type of sexual encounter that you can imagine, including a graphic incestuous rape of a father to [sic] his 11-year-old daughter.”

There are some who insist books should not trouble us, scare us or cause us “anguish”—as one of Florida’s new education laws put it. Yet many of our fellow citizens have suffered far more in real life.

The thing is, this country includes Native American people, Black people, Asian people and Latinos. Kids experiment with sex and drugs; kids struggle with gender; some kids are abused by their parents; some kids even kill themselves. This stuff is real and important. Are writers just supposed to ignore the world we live in?

I write books of my own, books about the history of my family, who were dirt farmers, Pilgrim Fathers, plantation owners, politicians, bus drivers, artists, segregationists and progressives. I write about how Florida has been a place of death: The conquistadors killed untold numbers of native peoples, both by the sword and with the pathogens they spread; and the land-hungry white Americans who arrived in Andrew Jackson’s bloody wake grew prosperous off the cotton worked by enslaved people. I also write about the beauty of this place, the turquoise waters, the ancient oaks, the panthers and the manatees and the wetlands singing with birds.

I also teach at FSU, in an old brick building not far from my original palace of imagination. My fellow professors and I are given to understand that we’re not supposed to assign certain books or talk about certain topics. We’re told to stay away from Pulitzer Prize-winner Nikole Hannah-Jones’ The 1619 Project, for example, because it allegedly undermines our simple, reverential understanding of the American Revolution and contradicts the state Department of Education’s claim that the U.S. is a uniquely good and virtuous nation. Sure, America accidentally enslaved some people but hey, the British did it first. Somehow, this highly praised—and also substantially criticized—collection of essays, poems and studies of how slavery shaped the United States has been defined as a cancer on the nation, instead of what it actually is: a provocative reframing of American history through the presence of Africans on this continent. It doesn’t always make for comfortable reading, no matter what color you are. Yet there are some who insist books should not trouble us, scare us or cause us “anguish”—as one of Florida’s new education laws put it. Yet many of our fellow citizens have suffered far more in real life.

The Right To Read

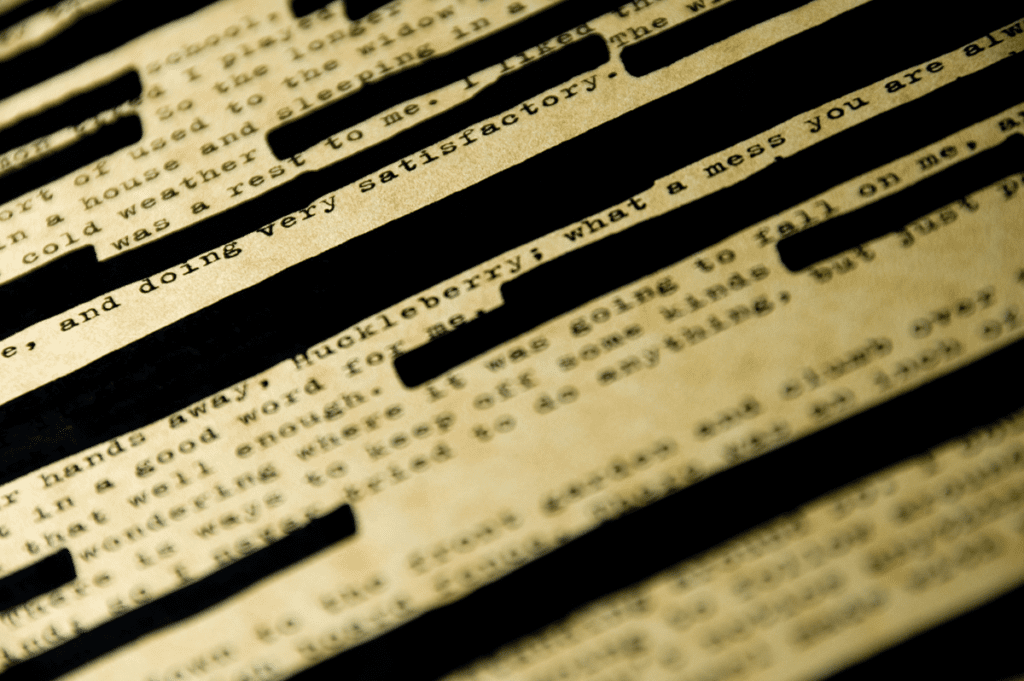

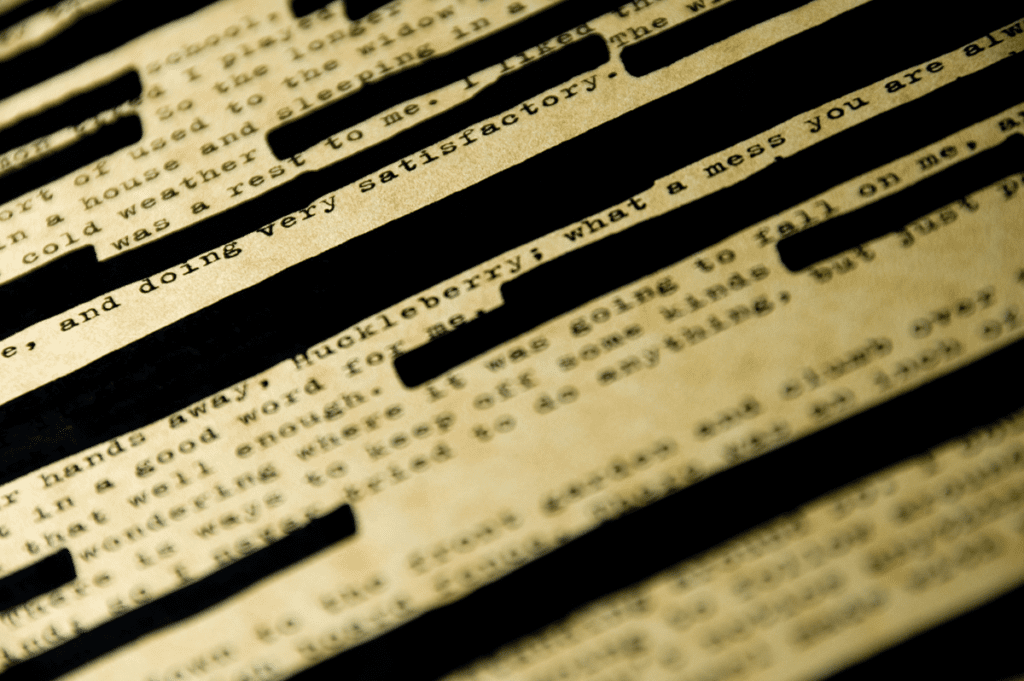

Literature has always been seen as a threat to the social order. In 1762, a teenage debutante named Kitty Hunter ran off with a married aristocrat. London society blamed novels for feeding Kitty’s romantic tendencies. Two centuries later, Ayatollah Khomeini, the supreme leader of Iran, was so freaked out by the 1988 novel The Satanic Verses, he accused author Salman Rushdie of blasphemy against Islam and offered a fat reward for killing him. Antebellum Southern states declared Uncle Tom’s Cabin illegal: It might inflame abolitionist passions. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, published in 1885, was promptly banned in Concord, Massachusetts, and other respectable burgs for ridiculing religion and irredeemable vulgarity. Then in 1905, the New York Public Library removed Twain’s masterpiece from the children’s reading room on the grounds that Huck is an unhygienic child, always itching, always scratching. In the last quarter of the 20th century, Huck Finn got banned in various school districts for completely different reasons, mostly because the N-word appears in the text 200 times.

One of the most telling examples of what really drives book banning occurred in 1960, when the publishers of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover were tried under Britain’s Obscene Publications Act. In the courtroom, a lawyer acting for the Crown asked, scandalized, “Would you approve of your young sons, young daughters—because girls can read as well as boys—reading this book? Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?”

Books give you ideas, and ideas can be terrifying, inspiring and world changing.

Yes, girls read: even the parlormaid! The prosecuting barrister Mervyn Griffith-Jones inadvertently revealed what censorship is really about. The powerful and the sophisticated might find certain books distasteful but see themselves as sufficiently tough-minded to withstand naughty literature’s siren songs. Those with less status and supposedly more malleable minds might stumble onto a text that could destroy their innocence, suggesting that sex might be fun, and love comes in all forms.

Books give you ideas, and ideas can be terrifying, inspiring and world changing. Some ideas are just stupid, shortsighted and hateful: white supremacy, climate change denial, antisemitism, misogyny, general bigotry. Those are poisonous and based on fear and lies. Ideas that have been tested in the crucible of honest interrogation and free inquiry help to set us free. Despite my freedom to read, I didn’t question some culturally embedded ideas, that, say, nature was eternal, or that Reconstruction was a disaster for the nation. But then getting my hands on Rachel Carson and Bill McKibben showed me that we are poisoning our only home, perhaps irrevocably. Black Reconstruction in America by W.E.B. Du Bois, Liberty and Union by David Herbert Donald, and anything by Eric Foner revealed that the period from 1865 to 1877 actually empowered Black people for the first time in American history.

There are dishonest books, yes, bad books, lying books. Yet the more you read, the more you know how to judge the story you’re being fed. You learn how to find information. You become equipped to recognize the toxic nonsense that batters us like a tornado. Knowing more is better than knowing less. Florida is supposed to be “free,” right?

When you hear that some politician or preacher or pundit says a book should be banned, exercise that freedom. Get it, and read it. I hope I never have to say to my students that certain wings of the palace of imagination are off-limits to them, that the labyrinth in the basement is too dangerous to enter—there might be a Minotaur down there!—or that windows looking out onto that enticing knot garden have been painted over and nailed shut. This is not education. This is not freedom.