by Diane Roberts | December 12, 2022

Take a Nostalgic Road Trip Through Old Florida on U.S. Highway 90

Diane Roberts journeys back to her grandparents' homestead in Northwest Florida, painting a picture of the past that’s equal parts painful and pretty.

America is latticed with storied roads: Hardtops we built to better ourselves or find ourselves or just light out. John Steinbeck called Route 66 the “mother road,” leading beaten-down Dust Bowlers to the promised land of California. Robert Johnson, Charley Patton and Son House birthed the blues along Route 61 between Memphis and New Orleans. U.S. 90, running from Jacksonville Beach to Van Horn, Texas, is not in that class of legendary. No one has declared it “scenic,” though the part that runs between the Suwannee River in the east and Holmes Creek in the west can be beautiful, with grassy hills and stands of oak and cypress. But for me, U.S. Highway 90 is a path into the past, an unspooling ribbon leading me through the Florida that was—the Florida before the interstates.

U.S. 90 was created out of a jumble of local roads in 1926 after the establishment of the United States Numbered Highway System. Under the asphalt, the thoroughfare is much older, a trail created by native people long before the conquistadors showed up. The Spanish made it their “royal road,” El Camino Real, running between the colonial capitals at Pensacola and St. Augustine.

For me, U.S. Highway 90 is a path into the past, an unspooling ribbon leading me through the Florida that was—the Florida before the interstates.

Long-traveled paths carry ghosts. Interstate 10, U.S. 90’s wider, newer shadow, will get you there quicker, but it doesn’t tell the same stories. When I was a kid in Tallahassee, it seemed like we were always on 90, sometimes going to Jacksonville to shop for what my mother called “better clothes” at May-Cohens and Furchgott’s, a lovely department store with strawberry-print dress boxes. Every July we’d drive the 25 miles east to Monticello, the Jefferson County seat, for watermelons picked right out of the fields. Jefferson is such a small county it still doesn’t have a stoplight today. Mostly, though, we headed west to The Farm (it always sounded like it should be capitalized), where my grandparents lived along with a cocker spaniel, uncounted chickens and 150 cows. My mother had been born and raised there, and she knew the mileage precisely: 82.3 miles from our house in Tallahassee to the back porch door in Chipley. We knew the towns and villages in between the way we knew the books of the Bible: Quincy, Gretna, Mount Pleasant, Oak Grove, Chattahoochee, Sneads, Grand Ridge, Marianna, Cottondale. In the summers, my brother and I spent a month at The Farm—separately. Our gentle grandmother hated it when we ran around whacking each other’s legs with Hot Wheels tracks, so she preferred to deal with one ill-tempered child at a time.

Sinclair Dinosaurs and Coca-Cola Stock

Once we crossed the Ochlockonee River heading west, the world became greener and stranger. Somebody had parked a brontosaurus in their front yard. I think it was a Sinclair dinosaur, the kind they used to put up at their gas stations, broccoli-colored and 15 feet high. We longed for one of our own. Quincy had no dinos, just big houses and fine churches dating back to the 1820s. Centenary United Methodist Church has a stained-glass window signed by Louis Comfort Tiffany. With a population of about 8,000, Quincy was once the richest town in America. During the Depression, a fellow named Mark Welch “Pat” Munroe, the local banker, encouraged his customers to scrape up some cash and buy Coca-Cola stock. The share price had plummeted from $40 in 1919 to $19. The ones who listened became millionaires. Of course, many of them came from landed families who, like everybody else, struggled during the 1930s, but weren’t especially bad off.

Beyond Quincy it’s a different story. The cotton and shade tobacco fields are gone, replaced by tomatoes, sod and nursery plants. Many of those harvesting the crops are Black, but also increasingly Latino. (Insider tip: Taquería Miranda on the western edge of town does great papusas.) The hamlet of Gretna, as poor as Quincy is rich, is now the unlikely home of a casino run by the Poarch Band of Creek Indians. You can bet on quarter horse races there or play blackjack, though gambling doesn’t seem to help the people who live there. Rusted Fords sit in front of small block houses too close to the road, scenes far from the coiffed palm trees and azure swimming pools our politicians want to be the world’s idea of “Florida.” Sometimes there’d be a little fruit stand in front of one of these houses, with a lady selling the cantaloupes, plums and Silver Queen corn she grew in her backyard. My mother would stop, and we’d buy some of everything.

Just before the spot where the time zone changes from Eastern to Central—weirdly, you could get there from Tallahassee a few minutes before you actually left Tallahassee—the landscape is lush but melancholy. Chattahoochee, an ancient settlement on the high bluffs above where the Flint, Chattahoochee and Apalachicola Rivers meet, was a sacred site for the Apalachee for more than 1,000 years. You can still see three of the seven great mounds they built near the confluence, a ceremonial complex that also functioned as an astronomical observatory. Somewhere nearby, the Spanish established a mission in the 17th century, now vanished into the kudzu. A fort built in 1816 to defend the southern border of the U.S. lies drowned in Lake Seminole, a reservoir created by damming the rivers in the early 1950s. The Florida State Hospital for the mentally ill, founded in 1876, looks deceptively serene, with its old white buildings, some of them with woodwork as lacy as a Victorian petticoat. In the 1830s, it was a munitions depot, supplying federal soldiers in the Second Seminole War whose job was to drive native people out of Florida. Then on the edge of Marianna, the next town over, is the notorious Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys. Now closed, this “reform” school was where scores of boys were beaten, tortured and sometimes killed. Untold numbers of boys are buried in unmarked graves in the fields, and it later served as inspiration for Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Nickel Boys.

Antebellum Gems and Farm House Follies

Before 1865, Marianna was a prosperous cotton town, with elegant houses and, right behind them, fields worked by enslaved people. The rich white folks lived large, at least until the Battle of Marianna on September 27, 1864. Union forces, including a detachment of U.S. Colored Troops, destroyed food stores, liberated 600 slaves and routed the Confederate volunteers. Johnny Reb and Billy Yank shot at each other across Lafayette Street, now the Marianna downtown stretch of U.S. 90. Marianna’s most distinguished citizen, Gov. John Milton, who knew the South was losing the war, rode home from Tallahassee in the spring of 1865 and, on April 1, apparently shot himself to death at his plantation house.

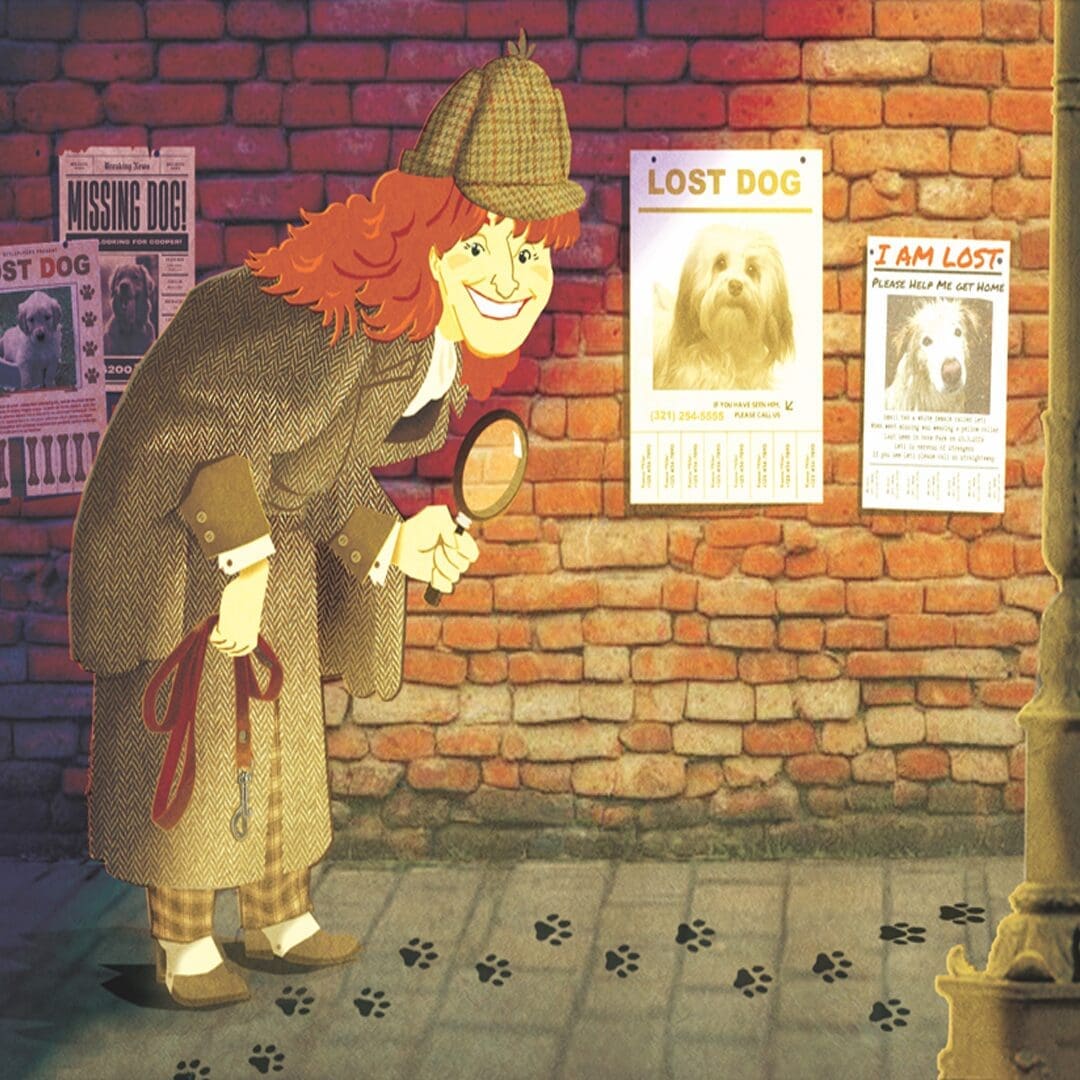

Every once in a while, we’d visit the caves, officially called the Florida Caverns State Park, a network of limestone caves opened up by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s, some tall as a cathedral, with spiky translucent stalactites and critters such as gray bats and blind crayfish. Most times though, our treat was parking for a couple of minutes to look at the RCA Records Victor dog in downtown Marianna. He sat above a shop door, maybe six feet high, head cocked at the oversized horn speaker of a gramophone. The other thing we loved was the Russ house, a 19th century mansion with a huge curved veranda precariously supported by disintegrating Corinthian columns. For years it was choking in wisteria vines, its floors sagging. I used to fantasize about buying it. Happily, somebody did, and now it’s fixed up and houses the Jackson County Visitor Center. Lots of the other fanciful columned and turreted houses in Marianna have been fixed up, too, painted in lavender, hyacinth blue and butter yellow.

Unlike Marianna, Chipley is not an antebellum gem. It wasn’t founded until 1882, and my grandfather, whose family has been in Washington County since the 1820s, wasn’t impressed: “I’ve got a mule older than Chipley,” he’d say. Instead of a pretty square with a courthouse, the town center is a railroad track, courtesy of William Dudley Chipley, a former state senator and Ku Klux Klansman who ran his railway from Pensacola to Chattahoochee. We’d turn off 90, driving past my grandfather’s pastures to the house, a low, sprawly place built in 1925 with window seats, French doors, and a cellar—an oddity in a state where if you dig down a few feet you usually hit water. If you’re wondering how a child spent her days on a farm in a house with two TV channels, well, Granddaddy and I went to the Piggly Wiggly and fished in the pond at the old farm where he grew up (and his father, and his father’s father), 10 miles from town. My grandmother took me to call on members of the Presbyterian Women’s Circle who served us iced tea and pound cake. Sometimes I visited my Great-Aunt Rilla, who ran her own flower shop out of the tall 1910 house built by my great-grandfather so that his children could go to school in town. I pet the noses of the red-furred Hereford cattle in the fields, played with baby chicks and read all my mother’s old Nancy Drew books (again and again). I was never bored.

Much of this world is gone. My grandparents died 40 years ago. Their house is still there, though whoever bought it after them tore some of it down, making it smaller. But the 300-year-old live oak in the front yard remains. Great-Aunt Rilla’s house is still a flower shop. The broad pastures where my mother gave me my first driving lessons are now full of duplexes, and the Piggly Wiggly has to compete with the Walmart Supercenter down by I-10. The magical critters, the RCA dog in Marianna and the Gadsden County Brontosaurus have disappeared. But on my stretch of road, the rivers and trees still whisper their stories, the past is still evident, and the old road still feels like home.