by Diane Roberts | May 2, 2022

How a Tallahassee Tradition Died a Quiet Death

It took Tallahassee locals 110 years after the Emancipation Proclamation to realize the May Party wasn't a celebration of the real south.

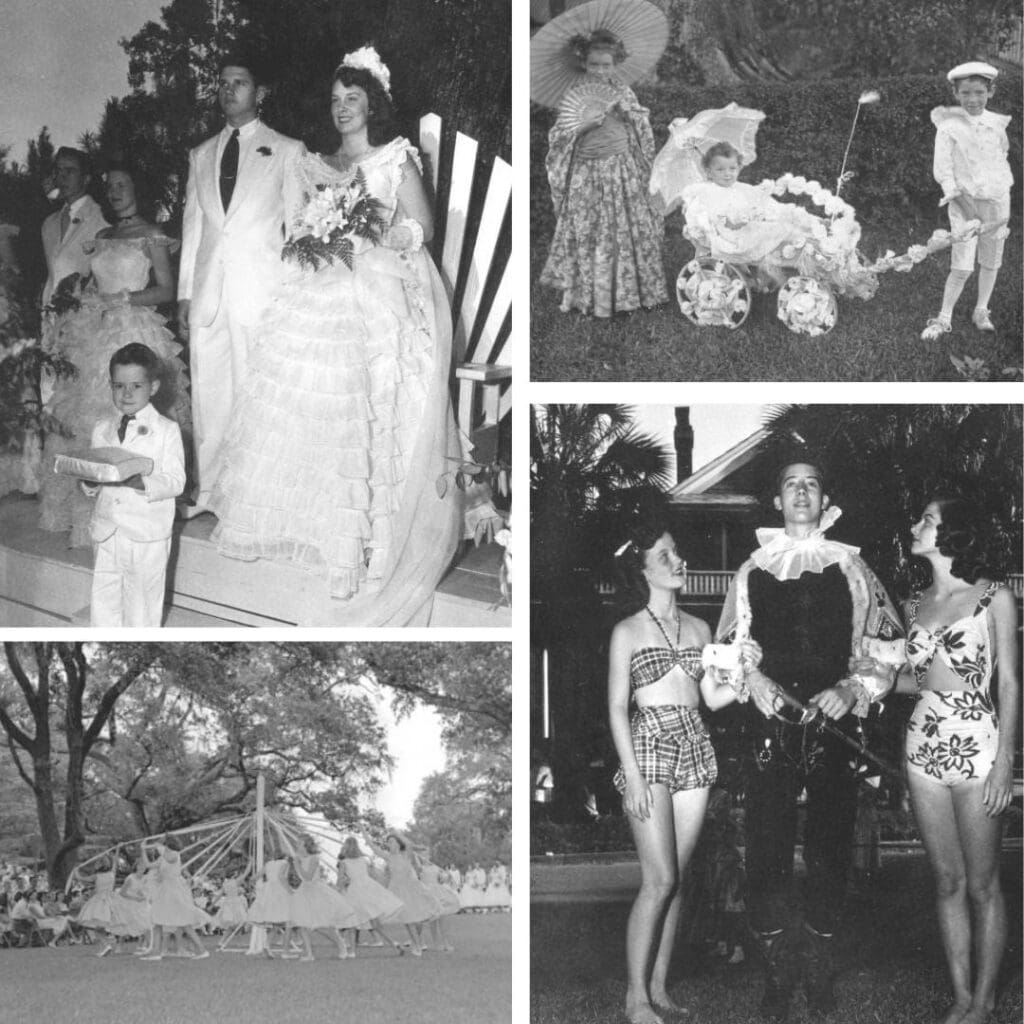

It was 1958, the year The Everly Brothers topped the charts with “All I have to Do is Dream,” the year cops in Montgomery, Alabama, arrested Martin Luther King Jr. for “loitering,” the year the U.S. Air Force accidentally dropped an atomic bomb over Mars Bluff, South Carolina, and the year there was a tie in the Tallahassee May Queen election. It was a bit like the contest between Aphrodite, Athena and Hera to decide which goddess was the most beautiful. There were only two Leon High School goddesses vying for the coveted title of May Queen, and, while nothing as drastically lethal as the Trojan War would result from the outcome, I expect there was a lot of drama and some pointed (yet genteel) attempts to dent the popularity of one or the other. There was no actual killing. Linda Gormley, the 1957 Florida-Georgia Junior Olympic diving champion, member of the student council and the Melodears (Leon High’s all-girl choir) as well as a cheerleader, ended up with the same number of votes as Faye Dunaway, a member of Civinettes, the Pierian National Honor Society, the Thespians and also a cheerleader. The runoff election to decide who would sit enthroned under the May Oak on May Day made the local newspaper, which sized up the competitors: “Miss Dunaway stands 5 feet, 7 inches tall and has brown hair and hazel eyes,” while “Miss Gormley is 5 feet, 6-and-a-half inches tall, has green eyes and blond hair.” On the second ballot, Linda Gormley edged out Faye Dunaway to become Tallahassee’s 123rd May Queen. She went on to enroll at Florida State University, pledge Kappa Alpha Theta and marry a lawyer named Curtis Genders. Faye Dunaway went on to enroll at Florida State University, pledge Pi Beta Phi and star in Bonnie and Clyde.

The May Queen was no ordinary pageant winner, not like your Cotton Queens or your Peanut Queens or your Watermelon Queens, obligated to ride on parade floats in rhinestone tiaras and sashes, open new Ford dealerships and hand out prizes at the county fair. There was no formal competition, no swimsuit round, no demonstration of flute-playing or baton-twirling. The top vote-getter, as chosen by the student body of Tallahassee’s all-white high school, won the title, while a dozen or so runners-up became the queen’s court. The May Queen did not advertise anything or raise money for charity. She just existed for one day in May wearing a white crinoline, sitting on a white fan-back chair under a huge live oak tree, flanked by boys in white dinner jackets and girls in petal-colored hoopskirts. For almost 140 years, she occupied a near-mythic place in the local mind. She may not always have been born into one of North Florida’s “old families” (though she often was), but social doors opened for her anyway; the ladies of the Tallahassee Garden Club, the Junior League of Tallahassee, the Daughters of the American Revolution and the United Daughters of the Confederacy celebrated her as the embodiment of “Southern femininity.” Of course, they meant white femininity.

The May Queen did not advertise anything or raise money for charity. She just existed for one day in May wearing a white crinoline, sitting on a white fan-back chair under a huge live oak tree, flanked by boys in white dinner jackets and girls in petal-colored hoopskirts.

We called the May Party “Florida’s oldest festival,” either not realizing or not caring that for more than a millennium, the Seminoles, the Mikasuki and, before them, the Apalachee had marked occasions like the Green Corn Ceremony with feasting and dancing. In 1833, when the first May Party was held, Florida had been a U.S. territory for a mere 12 years. Still, the May Party wreathed itself in the pink mists of romantic antiquity, as if its line reached all the way back to Camelot. The Floridian newspaper reported on May 6, 1848, that the “coronation of the Queen of May is an ancient ceremony, handed down according to forms with no essential change, from the days of the Tudors and Plantagenets.” The white folks who grabbed the good cotton land of North Florida and brought in enslaved Africans to work it were dedicated readers of Sir Walter Scott. They called their houses Waverley, Whitehall and Loch Achray, names taken from his novels. Inspired by the tournament in Scott’s novel Ivanhoe, the sons of local landowners staged jousts, dressing up in tin armor and velvet surcoats, taking chivalric “noms de guerre,” which is French for an assumed name: the “Knight of the Mists,” the “Knight of Ochlockonee” and “Robert Bruce.” They’d ride full-tilt at each other with pine lances in a little valley near where the Tallahassee Whole Foods is now. Whoever managed to stay on his horse longest got to crown his chosen local debutante “Queen of Love and Beauty.”

Back then, the plantation class inhabited a mental Middle Ages, imagining themselves feudal lords and ladies presiding over a pastoral society where everyone lived lives of probity, Christian charity and impeccable manners. The enslaved people who picked the cotton, cut the sugar cane, cooked the food, cleaned the house and otherwise enabled this supposedly “pretty world where Gallantry took its last bow,” as Gone with the Wind called it, did not trouble the dominant narrative of benign masters and content slaves. Indeed, they barely registered in it. When I was a child in the 1960s, I was dimly aware that sometimes the police weren’t very kind to Black folks and that a good man called Martin Luther King Jr. was trying to make things better. All that seemed far away from Tallahassee, a town full of white-columns and old rose gardens, where you could run into May Court ladies at church and May Queens at the Jitney Jungle. My mother’s best friend had been on the May Court in 1947 and her sister in 1953. In the fourth grade, Mary Weedon Drake and I used to recreate the May Court with our Barbies on the floor of her living room. A portrait of the 1949 May Queen, Mary Weedon’s mother, Mary Leslie, hung over the mantel. She was ethereal, almost translucent, her long neck rising out of a misty confection of a dress, her face framed with red gold hair. At the 1969 May Party, Weedon and I and other girls in our class danced around the maypole. Actually, there were two maypoles, white-painted wooden things that looked like pegless hat racks with pink, green and yellow ribbons. We sang “Sumer is icumen in, lhude sing cuccu,” which we learned in chorus and did not understand, while half of us circled one way, half the other, trying to braid the ribbons on the pole. Mostly, we knotted them so badly somebody would have to use a hedge trimmer to cut them off.

Our mothers may have heard of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and “women’s liberation,” but feminism had not—and never would—penetrate the May Party.

I was in college when I learned that some folklorists think the maypole is a phallic symbol and May Day merrymaking a pagan throwback to the Roman festival of Floralia, known for its nude dancing. In the Middle Ages, peasants chopped down trees, decorated them with flowers, drank a lot of mead and got up to all kinds of naughty business. In 1627, Governor William Bradford of Massachusetts was outraged by May Day in New England, blasting the “beastly practices of ye mad Bacchanalians” with their “wanton ditties.” Sadly, there were no wanton ditties, no Bacchanalian carryings-on, and certainly no nakedness at the Tallahassee May Party. The Garden Club would not have tolerated it.

The May Party had a yearly theme: “The Days of Robin Hood,” “The United Nations,” “Florida Under Five Flags.” After our maypole dance, we stood there in Lewis Park, watching Leon High School kids act out “Florida, Land of Flowers” with wreaths of baby’s breath, phlox and pinks, performing a sort of minuet. I wondered what it would be like to be the May Queen dressed in 30 yards of ruffles, crowned with roses, her mascara discreet, her lipstick sugar pink, her shining hair curled on milk-colored shoulders. How would it feel to be so admired, so desired, the “Southern Belle” of the nation’s retrograde dreams. Our mothers may have heard of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique and “women’s liberation,” but feminism had not—and never would— penetrate the May Party.

Almost everyone was white. Students at Lincoln, the “Negro high school,” were not invited to participate. A handful of housekeepers and yard men sometimes watched the show from the front yards of the big houses surrounding the park. The year I was a maypole child, the Florida A&M Marching 100 played at the May Party. I suppose I noticed they were Black. I don’t recall. I just remember how their gold-braided uniforms glinted in the sun. I was oblivious to how the ghost of Jim Crow troubled us all. Black schools held separate May Day celebrations with skits and pageants, but they were never invited to Lewis Park. In 1963, Leon High School officially integrated, admitting three Black students. Florida State University integrated in 1963 and in 1970, chose Doby Lee Flowers, a Black undergraduate, to be homecoming queen. It was surely inevitable that one day a Black girl would sit in the big white chair under the May Oak. Old Tallahassee, by which I mean upper-middle-class white families, didn’t rail against social change—not publicly, at least—and they didn’t vow to keep the celebration all-white. They looked around, 110 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, and finally understood that hoopskirts and “Dixie” were out of fashion. In 1974, the May Party died a quiet death, giving no trouble. Old Tallahassee lamented its passing. My great-aunt Vivienne shook her head. This modern world might call it progress, but, as she said, “What about romance? What about beauty?”

The city hit upon a new festival to showcase Tallahassee’s flowers and all that history, hoping to impress the state legislators who suggested maybe the capital of Florida ought to be somewhere more convenient, somewhere with a bigger population, somewhere like Orlando. “Springtime Tallahassee,” the May Party’s replacement, was run by white country club types who decided that a parade with a banker or realtor dressed up as the genocidal Andrew Jackson, who was territorial governor of Florida for about nine months in 1821, and floats with middle-aged ladies in hoopskirts and bonnets and white men in greasepaint and feathers pretending to be Seminole Indians would not only charm the powerful, but bring in revenue.

After a night of high wind in August 1986, the May Oak collapsed. It was old, maybe 200 years old, and had long been dying from the inside. When the city landscaping crew sawed it down, they left the stump. It’s six feet across and still presides over Lewis Park. A group of local Wiccans called the Church of the May Oak used to meet there, but I’m not sure they still do. Tourists and visitors to Tallahassee’s Chain of Parks Art Festival sometimes pause at the historical plaque, no doubt wondering what kind of people preserve a tree stump. They don’t know that this is at once sacred and tainted ground, the place where the white South wrapped itself in congratulatory myths, the grass where generations of young women paraded in satin shoes, the spot where Faye Dunaway, one-time Tallahassee girl, plotted her glittering future and stood smiling, a first runner-up Athena to the Aphrodite who won that year’s flowery crown.