by Diane Roberts | May 28, 2018

Grahamelot: Gwen Graham’s Race to Become Florida’s Next Governor

Graham wants to move back into her old house—the governor’s mansion—and take the office once held by her father, Bob Graham. Can she break the Republicans’ 25-year run?

Gwen Graham is interested. She fixes you with a brown-eyed gaze as warm as a May afternoon and asks, “How’s your family? How are your students? What should the state of Florida be doing to help our universities get to the next level? And what about campus safety issues?” Then she listens to what you have to say, nodding. You can’t help but be reminded of her father, Bob Graham, a former Florida governor and U.S. senator, except she doesn’t whip out a little pad to take notes.

We’re sitting down to lunch at the Uptown Cafe, a beloved Tallahassee joint that’s not, despite the name, particularly “up town.” I’m supposed to be interviewing her: She’s running for governor. But, at times, you’d think she was interviewing me. This is a trademark Graham move, at once endearing and intimidating. I can only assume the relevant information is being stored in the political data banks of the formidable Graham brain.

I’ve known the Graham family since they lived in the governor’s mansion in Tallahassee. In the mid-1980s, I was a young political columnist at the Florida Flambeau, often trying to satirize the legislature and the governor. The legislature was an easy mark, but Gov. Graham, a man who never took himself too seriously, was funnier about himself than I ever could be. He once composed a campaign song titled “I’m a Graham Cracker,” which he will still sing if you ask him, and sometimes when you don’t. In 1986, he swept into the annual Capitol Press Corps Skits to a fanfare played by the Florida A&M Marching 100. Wearing a braid-festooned uniform, mirrored shades, and the sash of a spurious order, he declared himself governor for life.

By then, Gwen Graham had left Tallahassee for law school at American University in Washington, D.C. In 1979, when she was 16, her father had become governor and moved his family of wife and four daughters to the governor’s mansion. Gwen already possessed a lot of poise. In an interview with the Orlando Sentinel during her father’s first year in office, she discussed being the eldest of four sisters, missing her friends in Miami, her classes at Leon High, and her attempts to diet in a house with a cook and a kitchen always full of tasty snacks. Long in the public eye as a politician’s daughter (her father had been an elected official since she was three), she said nothing controversial or even bratty. She did, however, allow the photographer to take pictures with her pet hamster balancing on her head, proving that she’d inherited some of her father’s sense of humor.

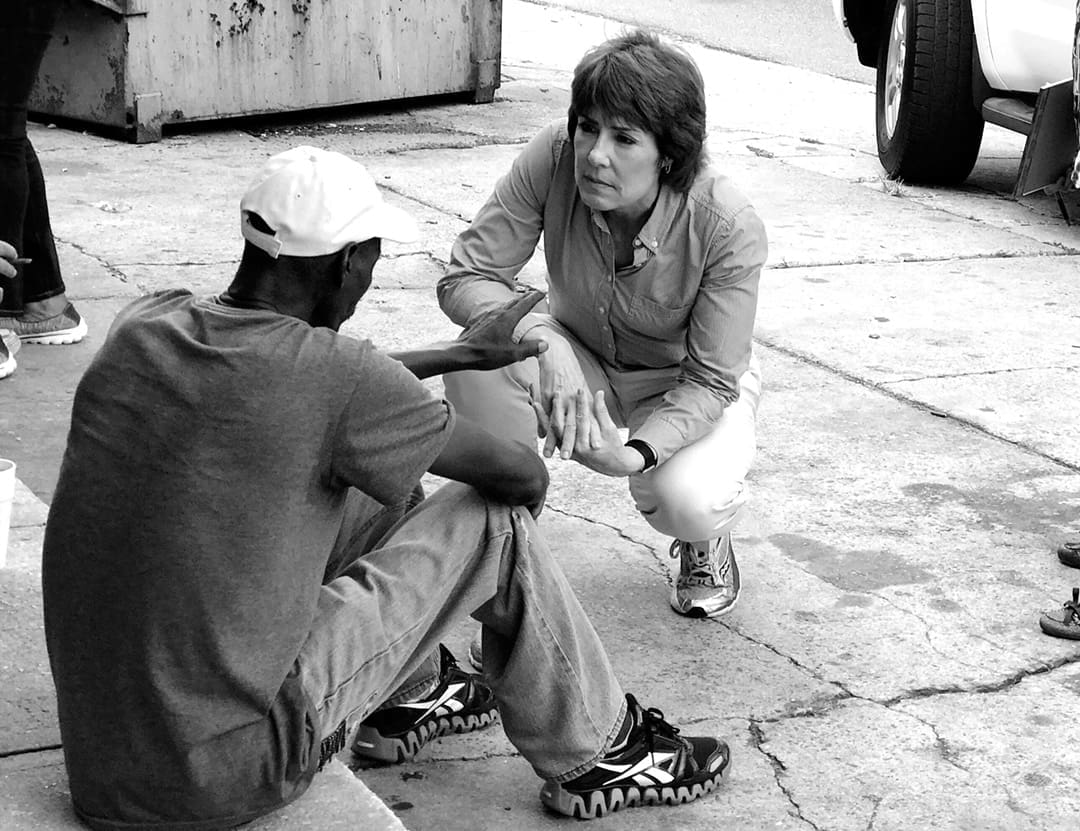

I have made a couple of microscopic donations (you can look ’em up) to Gwen Graham, both when she ran for (and won) a seat in Congress from North Florida and when she declared her candidacy for governor. That doesn’t mean I agree with her on everything. But the Grahams love Florida. And they’re fascinated by people—all people. I once escorted Bob Graham, then a newly retired U.S. senator, from the guest parking lot at Florida State to the university president’s office. The walk should have taken three minutes. It took us more than 30. Bob Graham stopped to talk to every human in sight, including a professor of French on her way to teach a class, a groundskeeper wrestling with marigolds in one of the flower beds outside the Westcott Building, and assorted phone-fixated, backpack-toting undergraduates who found themselves quizzed about their majors, their career goals, and whether they’d considered going into public service.

Gwen Graham shares her father’s politico-emotional intelligence. Here in the Uptown Cafe, she gets the waitress’s name, hands her a card and asks if she doesn’t think it’s time a woman was in charge of the state. “I’m going to be the next governor of Florida,” Graham says. A guy she hasn’t seen for years walks up to our table. She greets him enthusiastically. Turns out he was her sister Cissy’s prom date in high school. “I’ll tell her you said hey!” says Graham.

Like what you read? Click here to subscribe.

Like her father, she’s good at remembering names and faces, but where he’s a master of the long handshake and the elbow grab, she’s a hugger. I haven’t conducted a scientific poll, but an informal survey of North Floridians in branches of Publix, at Boss Oyster in Apalachicola, and on a Wakulla Springs jungle cruise suggests few North Floridians over the past few years have avoided being on the receiving end of a Gwen Graham hug. She hugged her way across the then-13 counties of Florida’s 2nd District during her run for Congress in 2014. The incumbent, Panama City mortician and Tea Party favorite Steve Southerland, accused her of being “Nancy Pelosi’s hand-picked candidate.” Graham pushed back, declaring she’d be independent, a centrist unafraid of bucking the Democratic party line. In the end, she edged out Southerland by 0.8 percentage points. D.C. Democrats were heartened—at least until she took her seat in the House of Representatives. Her first vote was against giving Nancy Pelosi another term as leader.

Now that she’s running for governor, the rest of the state is fixing to experience the Graham embrace. She kicked off her gubernatorial bid last May in Miami Gardens, a sentimental choice given that her father conducted the first of his famous “workdays” nearby in 1974. Bob Graham made workdays a tradition in 1977, spending occasional eight-hour days doing the jobs of ordinary Floridians to understand something of what their lives were like. Gwen Graham now does her own “workdays,” which have seen her preparing bread dough at La Segunda Central Bakery in Ybor City, packaging ice cream in Marianna, stocking shelves in a Kissimmee grocery store, putting together care packages with the USO in Pensacola, and installing solar panels on a roof in Orange County. Announcing her run in Miami Gardens, so close to her hometown of Miami Lakes, the town the Graham family founded, helped remind South Florida that she’s a local. The choice of Miami Gardens was also strategic: The city became infamous in 2013 for the “working while black” story of Earl Sampson, who was stopped 258 times, searched more than 100 times, and jailed 56 times in four years by the local cops, all for “trespassing” at the Quickstop convenience store where he worked. In choosing to kick off her campaign in a majority-black city with substantial numbers of Cuban-American, Bahamian, Jamaican, Dominican and Puerto Rican residents, Graham signaled her determination to build a coalition of Old Florida and New Florida. She’ll need them both to turn out in order for her to win the Democratic primary in August and then, if she makes it that far, to show up to the polls again on November 6th if she is to have a chance in the general election.

It won’t be easy. Among the Democratic hopefuls, Chris King, described by Tampa Bay Times columnist Adam Smith as a “bleeding-heart businessman, Harvard graduate and Jesus-loving philanthropist,” has little statewide name recognition, but he has committed $1 million of his own money to his campaign. Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum is favored by the more progressive wing of the party, but he’s also been hampered by an ongoing FBI investigation into the dealings of members of the Tallahassee City Commission. Former Miami Beach Mayor Philip Levine, whose campaign account is fat with cash (some of it his own), touts his business experience in contrast to Graham’s. At a January campaign stop in Tallahassee, Levine said, “The fact that I’ve had that weird thing in my background called a job, the fact that I’ve actually done something in my life outside the public sector is probably a big differentiator.” Many women interpreted that as a gendered insult, especially since Graham has held a variety of jobs, from attorney to school district administrator. Former Florida Commissioner of Education and Graham supporter Betty Castor rebuked him: “Philip Levine can lecture women on what it means to have a job and ‘do something’ with our lives after he raises three children while volunteering at their schools and working 50 hours a week.”

Leading up to the Democrats’ first debate on April 18th, Graham’s three male rivals went after her as the presumed favorite, faulting her votes in Congress to slow the stream of Syrian refugees admitted to America and change the definition of full-time employment under the Affordable Healthcare Act from 30 hours a week to 40. King knocked her for accepting campaign contribtions from Florida’s megabucks sugar industry while in the House of Representatives. Gillum accused her of being weak on gun control. Graham shot back, pointing out that the NRA spent $300,000 trying to derail her congressional campaign. Assailed from all sides in the debate, Graham sighed: “It’s OK. Gwen and the men.”

Graham, 55, could make history in November by becoming Florida’s first female governor. She’d also be the first Democrat elected to the state’s top office since 1994. To get back to the mansion she once called home, she’ll have to prevail over the men in her primary, then another man, a man who will certainly be flush with campaign cash from Florida’s Republican-favoring big business lobbies. The insurgent paleoconservative U.S. Rep. Ron DeSantis, President Donald Trump’s favored candidate, is expected to be a formidable fundraiser. As of mid-April, Republican heir apparent Agriculture Commissioner Adam Putnam reported $20 million in his campaign account, more than twice the amount Graham had raised, much of it from Florida Crystals and U.S. Sugar. Graham has now vowed she won’t take campaign contributions from Big Sugar; indeed, she has donated $17,400, the amount sugar industry–associated PACs gave her campaign in 2015 and 2016, to organizations supporting Everglades restoration and migrant workers.

Both Graham’s critics and some political experts wonder if she’s trying to ride her father’s popularity back to Tallahassee. Florida has changed a lot since the 1990s. When Bob Graham finished his second term as governor, the population was 12 million; it’s nearly twice that now. Carol Weissert, director of the LeRoy Collins Institute at Florida State University, says, “It’s been a long time since a Graham was on the ballot. Given our population growth, you can’t rely on the name statewide.” Or, as veteran journalist Lucy Morgan, former Tallahassee bureau chief at the Tampa Bay Times, says, “Many of these new Floridians don’t know Gwen from Adam’s house cat.”

Still, the Grahams are a famous family. Bob Graham’s older half-brother Philip and his wife, Katharine Graham, were owner-publishers of The Washington Post. Gwen’s first cousin, Lally Weymouth (Philip and Katharine’s daughter), is a well-known journalist. In July last year, a Miami New Times headline breathlessly announced, “Florida Dems’ Frontrunner for Governor Spent Weekend Hanging with Jared Kushner, Ivanka Trump.” Graham, along with her father, had attended a posh party in the Hamptons, where the impressive guest list included Steven Spielberg, George Soros, Margaret Carlson, Carl Icahn, David Koch, U.S. Sen. Chuck Schumer, and other boldface names. Graham didn’t, in fact, “hang” with Trump’s daughter and son-in-law; nevertheless, she can’t always avoid being seen as part of the dreaded “elite,” even at her cousin Lally’s party. Asked if she feels entitled as the daughter of a former U.S. senator and Florida governor, Graham just laughs. “Here’s how I respond to that. I say I’m so lucky—lucky to have had Bob Graham’s example of public service before me every day of my life.”

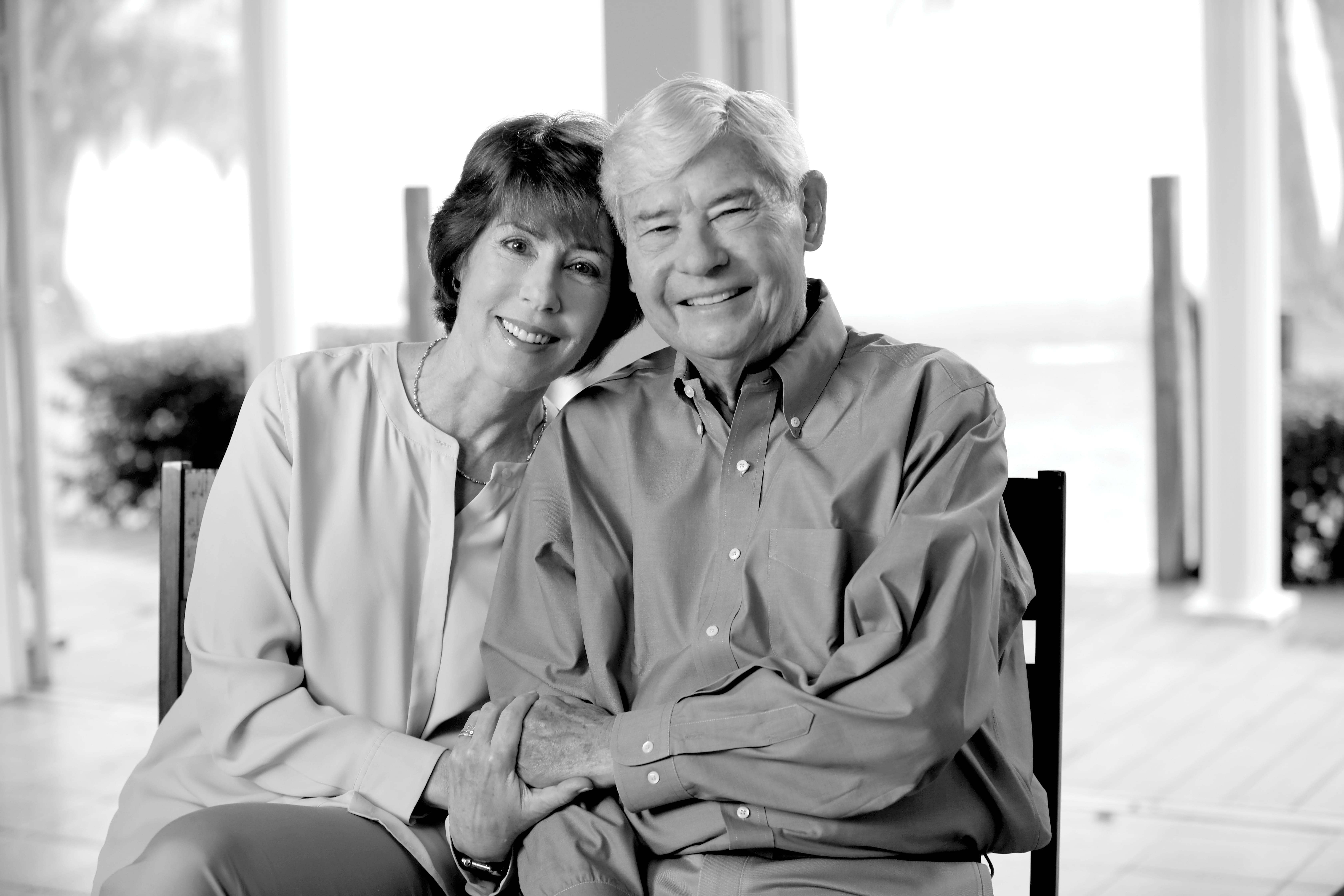

Clearly, Graham will have to show that she’s both her father’s daughter and her own woman. She left Florida for college, enrolling in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she pledged Delta Delta Delta, her mother’s sorority. Apparently, she was more of a reader than a hell-raiser. Graham’s husband Steve Hurm, whom she married in 2010, says the two of them bonded over their shared love of books. Graham was a single mother of three (she divorced her first husband, lawyer Mark Logan, in 2005). Hurm was a former beat cop from Pinellas County who went back to school, became a lawyer, and now runs Florida State University’s Policing Research & Policy Institute. They met in Tallahassee when he was working for the Florida Department of Law Enforcement and she was an attorney for Leon County Public Schools. Graham and Hurm revealed in 2016 that he had stage 4 prostate cancer. Graham said at the time she would delay any decision about running for governor until they saw how his treatment progressed. “I couldn’t do it without him by my side,” she said at the time. “I wouldn’t do it without him by my side.” In 2017, they announced he’s in remission.

Graham remains close to her grown children, her parents, and her three sisters. While Hurm holds down the fort at their Tallahassee house, she has moved her campaign HQ and her youthful staff to Orlando, right in the middle of this logistically difficult state. “I’m renting down there,” she told me. “It’s me and the millennials.”

She seems to define herself not as a lawyer or a politician (though no politician ever likes to be called a politician) but as a mother. She says she’s all for creating “jobs, jobs, jobs,” as the current occupant of the governor’s office is fond of repeating, but she wants those jobs to be good ones, with a future in a Florida where the environment hasn’t been poisoned; the old, the sick and the poor are taken care of; and the government pays more than lip service to schools. For the past 20 years, the Republicans have mounted what she calls “an all-out assault on public education.”

If you want to address inequality, poverty, the opioid crisis, and wage stagnation, “it all begins and ends with education,” she says.

Public education is a Graham family passion. Gwen’s mother taught school in Florida and Massachusetts. Her grandfather Ernest “Cap” Graham, who founded the family dairy farm in Dade County and served in the Florida senate from 1937 to 1944, pressed the legislature to establish a public university in Miami. His bill failed, but the Graham family kept advocating, and, in the late 1960s, helped make Florida International University a reality. When Cap Graham’s youngest son became governor, improvement of educational institutions became his priority. In 1983, he vetoed the state education budget, castigating the Democrat-controlled legislature for their “willing acceptance of mediocrity.”

These days, it’s the Republicans who seem willing to accept subpar public schools. Some of them, as Graham points out, “are making money off private education.” Florida House Speaker Richard Corcoran’s wife founded Classical Preparatory School in Pasco County, and his brother lobbies on behalf of for-profit schools. Rep. Manny Diaz, R-Hialeah, sits on the House Education Committee and also draws a six-figure salary as chief operating officer of Doral College, a private junior college that sells its services (i.e. classes) to charter schools.

“Nine out of ten Florida kids go to public school,” says Graham. “Let’s make our schools a public resource.” She proposes a holistic approach: public-private partnerships for healthcare in schools, opportunities for senior citizens to volunteer at schools, and no guns. Like most Florida Democrats, Graham says she supports the Second Amendment, but she also wants what she calls “common sense gun safety” and the banning of assault weapons. She says that as governor, she will ban AR-15s and their ilk, citing Florida Statute 14.022, which gives the governor power “to prevent overt threats of violence or violence to the person or property of citizens of the state and to maintain peace, tranquillity, and good order in the state.” Arming teachers, she says, is not the answer.

Some political observers question whether education is a winning issue in Florida. Carol Weissert says, “There’s not a lot of evidence people care about education. Retirees don’t care: Their children went to school in Michigan. Obviously, the Florida legislature doesn’t care. The environment might be more of a winner for Graham.”

Certainly, Graham is positioning herself as a strong defender of Florida’s wetlands, wild lands, and water. She’s against fracking and offshore oil drilling, calling U.S. Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke’s “deal” with Rick Scott to exempt Florida from the Trump administration’s plan to erect oil wells anywhere and everywhere, regardless of the risk to the ecosystem, “a political charade.” Some environmentalists charge that she’s not really as green as she paints herself, pointing to her vote in favor of the Keystone pipeline while in Congress. She answers that she voted yes on the grounds that the Canadians were going to extract the crude from the Alberta oil sands no matter what. She adds that a pipeline, however undesirable, is a safer mode of transporting dirty oil than trains or trucks and contributes less to carbon emissions overall. She’s definitely not a climate change denier. Unlike Gov. Rick Scott, she says, “I believe in science.”

Graham’s fellow Democrats broadly agree on Florida’s need to address rising sea levels and restore Florida’s greatest natural storm-water filtration system, the Everglades. “Our water quality is central to our economy,” she says. Graham’s strong environmental stances may not be enough to assuage those, especially on the Democratic Party’s left, still angry over the Keystone pipeline vote. Lucy Morgan warns, “She needs to overcome the anger of some Democrats who should be her devout supporters. She needs to shore up her base.”

There are many variables in any statewide Florida race. Will turnout be higher than usual? Will young people actually show up? Will women be energized to vote for Graham? Democrat Alex Sink lost to Rick Scott by one percentage point in 2010, an election in which only 49 percent of voters turned out. Will Trump boost Republicans or drag them down? Most of all, who’ll get the big money? “Florida has ten media markets,” says Carol Weissert. “You’ve got to have a lot of money to compete. As far as Gwen Graham goes, I’ll be watching the money.” Lucy Morgan thinks Graham needs to get on television well before the primary, “She’s a good candidate, but she needs to do a better job of marketing herself.”

Graham knows she’ll have to find a way to attract Florida’s disparate voters and remain true to her centrist impulses, as the Goldilocks candidate: not too conservative and not too liberal, a sweet spot few Democrats have found. Nevertheless, she’s confident. As the waitress returns to pour some more iced tea, Graham says, “This is the race I was born to run. And win.”

WHO’S WHO IN THE RACE

Democrats:

Gwen Graham

Former U.S. Representative // Tallahassee

Plans to expand health care, improve public schools and protect the environment

Andrew Gillum

Mayor of Tallahassee // Tallahassee

Wants universal healthcare, higher corporate taxes to better fund schools and a $15 minimum wage

Chris King

CEO of Elevation Financial Group LLC // Winter Park

Believes in higher-paying jobs, more affordable housing and more transparent government

Philip Levine

Former mayor of Miami Beach // Miami Beach

Running for better education, environment and economy

Republicans:

Ron DeSantis

U.S. Representative // Palm Coast

Cares about education, the economy and reshaping Florida’s court system

Adam Putnam

Florida Commissioner of Agriculture // Bartow

Touts conservative principles, smaller government, protecting Second Amendment rights and supporting veterans