Flight 401 Down in the Glades

The harrowing tale of three survivors of the 1972 crash of Eastern Airlines flight 401 into the Everglades

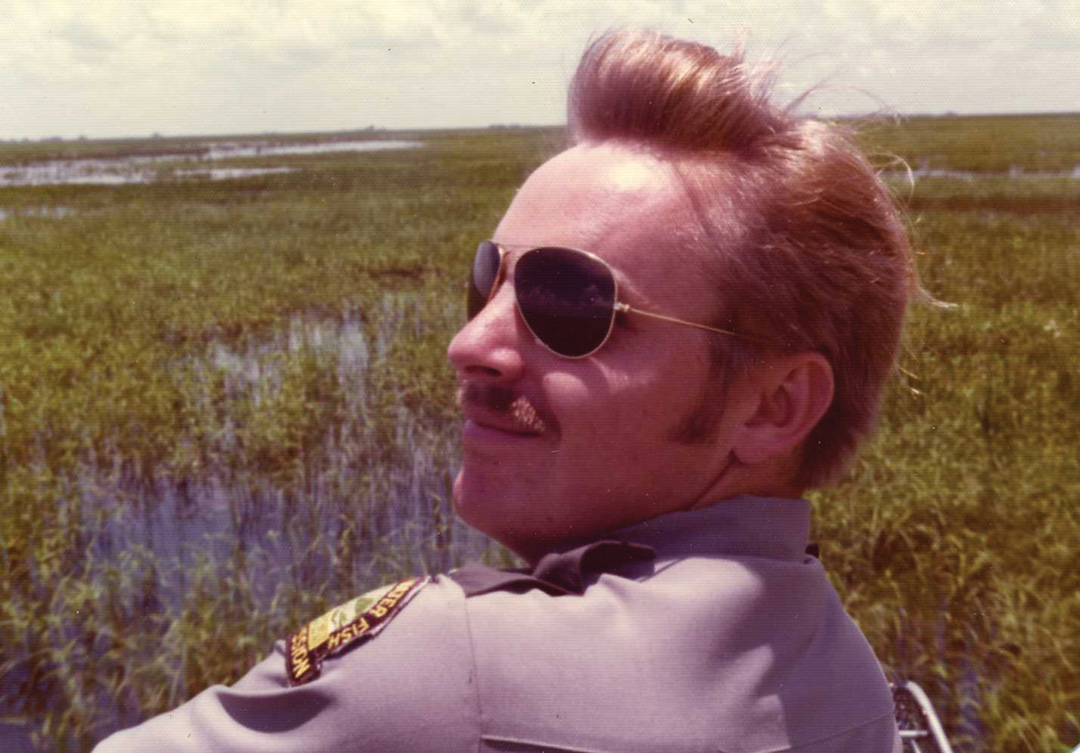

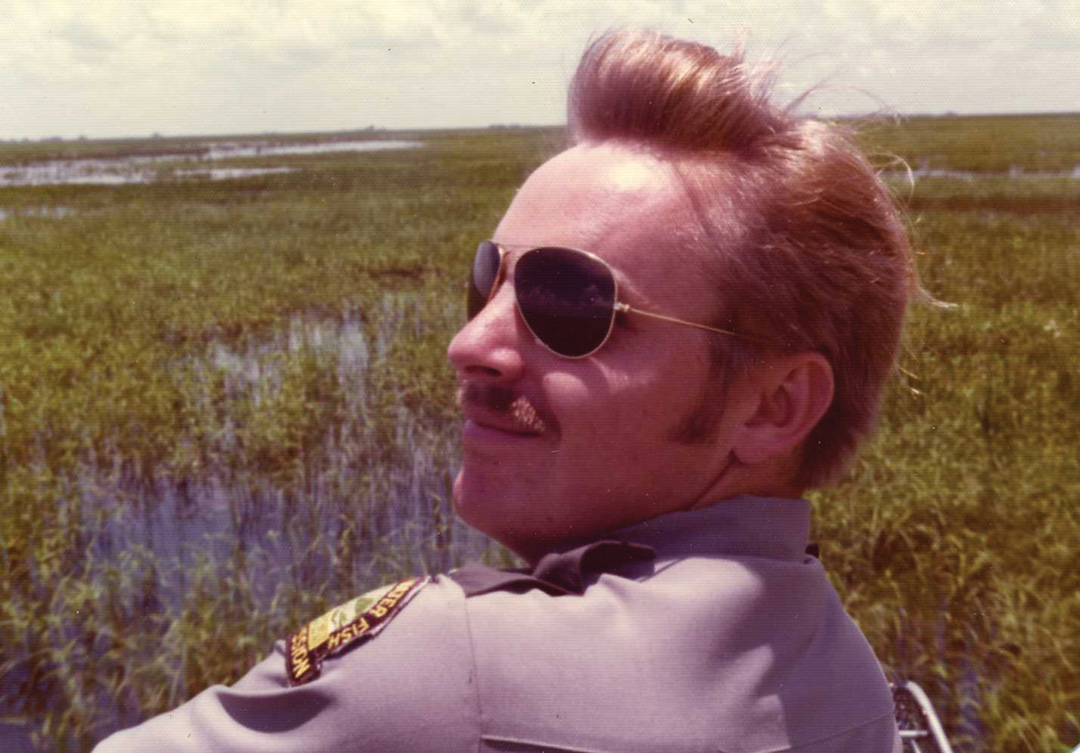

Forty-five years ago, when Officer Gray Leonhard of the Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission began a solo night patrol in the Everglades, he was on the lookout for poachers, drug smugglers and maybe even a bullet-riddled corpse. Instead, he would witness the first jumbo jet crash in U.S. history.

On the clear, moonless night of Dec. 29, 1972, a young rookie game warden sat behind the steering wheel of a light-green 1969 Plymouth four-door sedan with a blue “gumball” emergency light mounted on the rooftop. His foot pressed lightly against the accelerator pedal as he inched down the south levee on the L-28 canal with his headlights off. Loose chunks of lime rock cracked and popped under the tires as he crawled ahead.

At the time, it was one of the worst civil aviation disasters the country had ever seen. In the days and weeks following the crash of Eastern Airlines Flight 401, recovery efforts captivated the nation, and perhaps because of its iconic, unforgiving, alligator-riddled crash site, the event has remained seared in the memories of Floridians for decades. From his vantage point atop the levee, Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission Officer Gray Leonhard, then 24 years old, had a commanding view across the vast darkened marsh. An elevation of only eight feet felt like being on a hilltop in the Everglades. The night was a balmy 72 degrees, the mosquitoes surprisingly sparse. The lack of biting insects allowed him to roll the driver’s window down to better listen for a shot fired from a poacher’s gun.

Leonhard put the car in park, cut the motor and stepped out. Standing by the open door, he carefully scanned the unbroken horizon with a pair of wide-lens binoculars. He felt a sense of mission as he looked out into the black swamp, knowing that his job required cunning and stealth.

The warden noted nothing of interest. No flicker from an air boater’s headlamp. No roar of unmuffled high-horsepower engines. No gunshots. The silence was broken only by the intermittent croaking of bullfrogs and the occasional rustle of tall reeds as an unseen creature passed through them. A pale glow lightened the sky above Miami more than 40 miles away.

Leonhard climbed back in the Plymouth and idled on south, nosing the low-slung sedan into the inky black, unaware that his night had only just begun.

Meanwhile, 1,100 miles to the north, an Eastern Airlines jumbo jet lifted off in bitter cold weather from New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport. The time was 9:20 p.m. Flight 401 was a short-haul flight to Miami.

Stewardess Beverly Raposa, then 25, noticed nothing unusual as the flight passed high over the Atlantic Ocean en route to Miami International Airport. The petite brunette stood just 5 feet 1.5 inches tall. She had been turned down by Trans World Airlines for a job because she was a half inch under the 5-foot-2-inch minimum height required for all stewardesses. Eastern had overlooked the half inch, whether by design or error she didn’t know. But, to play it safe, she always wore an add-on hairpiece and teased her hair up into a bouffant to make herself look taller.

Raposa smiled cheerfully while she collected empty drink cups and dishes from the passengers. The only thing she was looking forward to on arrival in Miami was going to bed. She was whipped.

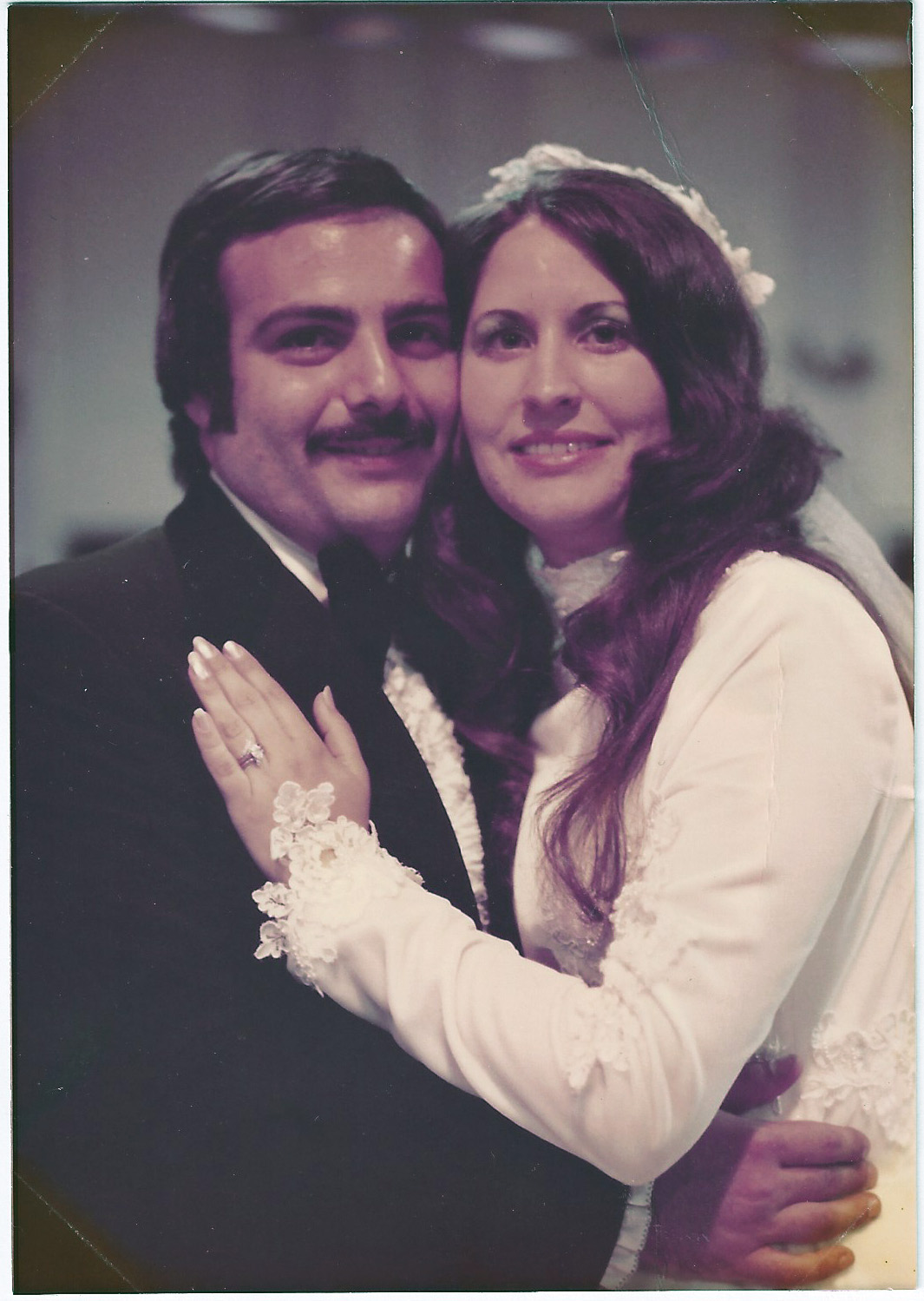

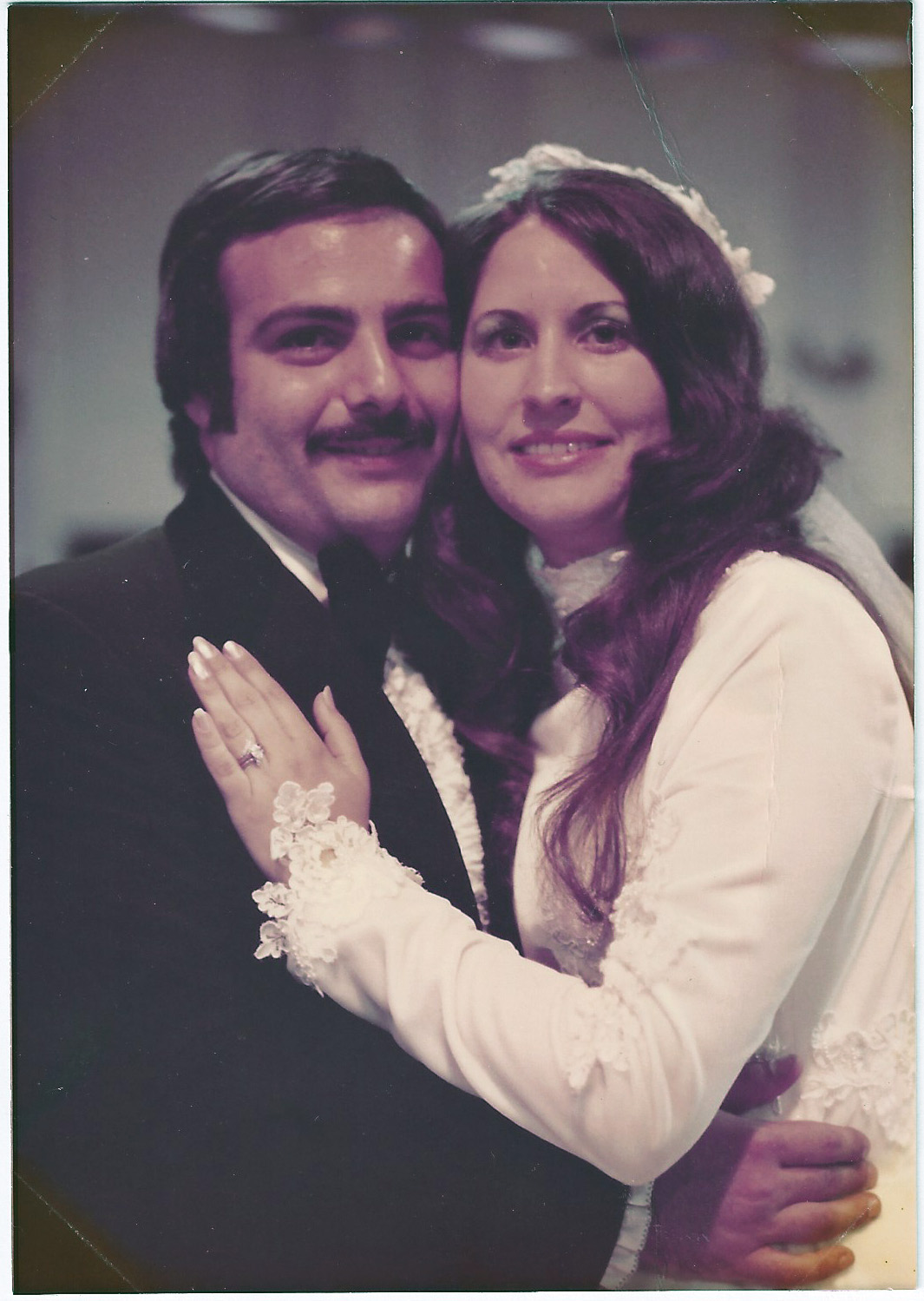

Sometime in midflight, passenger Ron Infantino switched seats with his wife, Lilly, after she returned from the bathroom. They’d been married only 20 days and were returning from their honeymoon. They were both 26 years old. At the time, the decision to change seats carried no meaning.

The captain and his first and second officers had every reason to feel good and confident about flying this particular ship. The Lockheed L-1011-1 Tristar was the latest generation of wide-body commercial aircraft and had been put into service only four months before.

In its first three hours aloft, Flight 401 had been uneventful. A trio of newly minted Rolls-Royce turbofan jet engines made a rumble that could barely be heard by the 163 passengers and 13 crew members seated inside the spacious cabin and reconfigured cockpit.

As the plane descended on its final landing approach to Miami International Airport, a cheerful voice boomed over the cabin’s loudspeaker address system: “Welcome to sunny Miami,” the captain announced. “The temperature is in the low 70s, and it’s beautiful out there tonight.”

The Infantinos were exhausted from celebrating Christmas with Ron’s parents in New York. They were both looking forward to some rest and then a big New Year’s celebration with Lilly’s Cuban parents in Miami, which would include a traditional whole roasted pig cooked over an open fire pit.

Ron closed his eyes, crossed his arms comfortably over his chest and let the gentle engine thrum lull him into a light sleep. Lilly leaned back in her seat, resting quietly.

At 11:32 p.m., Capt. Robert A. Loft, then 55 years old, with 30 years’ experience and 29,700 flight hours under his belt, attempted to lower the landing gear. A light on the instrument panel the first officer was monitoring failed to illuminate green to confirm that the nose landing gear was extended and locked.

Two minutes later, Flight 401 called the air traffic control tower. “Tower, this is Eastern … 401, it looks like we’re going to have to circle. We don’t have a light on our nose gear yet.”

“Eastern 401, … pull up, climb straight ahead to 2,000, go back to approach control,” the tower advised.

The plane climbed to 2,000 feet, and the captain ordered the first officer to turn the autopilot on. He hoped the circling delay would give them time to fix the problem.

Flight 401 soared above a primordial swampland filled with poisonous snakes and alligators crawling through razor-sharp sawgrass and open-water sloughs. With almost twice the area of Rhode Island, the largest subtropical wilderness in the United States has some of the most formidable terrain on Earth.

Inside the plane’s cockpit, the crew was trying to slide in a replacement bulb, a roughly two-square-inch all-in-one light assembly unit covered by a translucent green plastic lens, valued at $12 altogether. But it kept jamming. At some point the captain inadvertently bumped the control wheel, knocking the autopilot partially off. The unintentional jar apparently caused the plane’s nose to tilt down a few degrees.

The altimeter showed a decrease in altitude, but none of the crew noticed. The plane was dropping from the sky at a rate of 200 feet each minute. Then an alarm chimed, signaling a 250-foot drop.

The crew members, however, were focused on fixing the wheel-light indicator. The problem had consumed all their mental energy. And now, no one was flying the plane.

At 11:42 p.m., the first officer said, “We did something to the altitude.”

“What?” asked the captain.

“We’re still at 2,000, right?” the first officer asked.

“Hey, what’s happening here?” the captain shouted.

A SMALL MISTAKE

Raposa sensed a different tone in the engines. It didn’t sound like they were in midair anymore.

Ron’s eyes blinked open upon hearing the engines roar to full power. Startled, and now fully awake, he wondered, “What’s going on here?” A former crew chief on a B-52 in Vietnam, he had a keener sense than most passengers about a plane in trouble. Then a sudden jolt rattled the aircraft. His last complete thought before losing consciousness was, “This is going to be one hell of a rough landing.”

In the cockpit, the first of six radio altimeter warnings began, signaling an impending crash.

It was too late to do anything.

The left wingtip banked into the marsh at 227 miles per hour. Huge gouts of mud and aquatic vegetation shot high into the air as 185 tons of screeching metal ripped into the muck and grass. A fireball rushed through the fuselage, and the plane began pinwheeling like a giant Ferris wheel spun loose from its mount.

To those who survived, the scene must have had an eerie end-of-the-earth feel, with wisps of gray mist swirling, a baby wailing, the groans from the injured and the dying. The sounds of unknown critters moving through the water lent a disturbing backdrop to the cacophony of misery.

Beverly Raposa stumbled out of the nightmarish apocalypse, hurt, disheveled and covered in clumps of dripping swamp grasses. She choked on the acrid fumes from the 43,000 pounds of aviation gas that had spilled from the plane and screamed, “Don’t light any matches!”

FROM AIRBOAT TO AIRPLANE

Leonhard happened to be looking southeast across the glades. “An orange glow suddenly lit up out in the marsh toward Miami,” he recalled. “It looked like someone had poured gasoline on a campfire, and poof, up it went.” Curiously, Leonhard never heard the impact. He was more than 25 miles away.

A few minutes later Leonhard’s radio crackled. “A jumbo jet crashed in the Everglades north of the Tamiami Trial,” his sergeant said. “Pick up your airboat and meet me at the Twenty Mile Boat Ramp. We’ll launch from there.”

Leonhard hit the gas as he toggled on the blue light and siren. He had to make a detour of some 50 miles before he would arrive at the boat ramp on the north side of the Tamami Trail.

By 1 a.m., the rookie warden had launched his airboat. Riding with him were two Federal Aviation Administration officials. “The area I was about to go in was uncharted territory for me,” Leonhard said. “We were in Dade County, and my patrol zone was Broward County to the north.”

During his airboat training, senior wardens of the Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission had told Leonhard, “Never stop or slow an airboat down in rank grass because you may not be able to power out of it. Once you become stuck in the glades, you could be there for a long, long, time.”

Those words guided Leonhard as his 14-foot patrol airboat bulldozed through dense walls of water-anchored grass. High in the distant black sky, beyond the harsh glare cast by his headlamp, was a circling star: the searchlight of a Coast Guard helicopter hovering over the crash site eight miles away. It became his navigation beacon.

Thirty minutes later, Leonhard and his passengers suddenly burst out of a thick patch of 12-foot-high sawgrass. The hull slingshot forward as it dropped a couple of feet down into an open-water slough.

Ten feet in front of them were what looked like two mannequins to Leonhard—a partially clothed woman lying faceup in the mud and a naked man lying facedown. She wore panty hose and looked like she’d been scalped with a razor. He was left wearing nothing but a necktie and belt pushed up under his armpits. The FAA guy sitting closest to Leonhard yelled, “Holy shit!”

“An airboat doesn’t have brakes,” Leonhard explained. “And before I had time to even let off the throttle or do anything else, I ran over those two people, who I knew were both dead. But we idled back around to double-check on them just in case.”

Though Leonhard was only a rookie, the sight of death was not unfamiliar to him. Two tours in Southeast Asia had hardened him.

Leonhard pulled his eyes away from the painful scene, lifted his head and slowly swung the stark-white beam of his helmet-mounted lamp across a massive trench carved in the marsh. More than a quarter mile long, the cone-shaped debris field was filled with an apocalyptic jumble of human carnage, personal belongings and aircraft wreckage. “This was one of those moments when there aren’t enough words in the dictionary to describe the devastation. Dead bodies hung, lay and floated everywhere I looked. But we knew our job was to rescue the survivors first. There would be plenty of time for body recovery,” Leonhard said.

Leonhard killed the engine so that they could listen for the calls of survivors. During a rare moment of calm after the rescue helicopter had departed for Miami, he heard the faint tune of a Christmas carol. Leonhard doesn’t remember which one. Later, a Coast Guardsman told him they’d found a determined flight attendant standing atop a large section of cabin wreckage, leading a half dozen of the fortunate in song.

SURVIVORS’ SONG

The last thing Raposa remembered seeing before she was knocked out was a waterfall of colors. When she came to, she was still belted into her seat, tipped to one side, hanging six feet above the swamp. The middle engine and tail section had broken away from the main fuselage, coming to a rest on their sides in a remote area far from the main crash site, which was located 18.7 miles northwest of Miami International Airport.

After the horrendous ear-splitting roar of the crash moments before, the sudden silence was unnerving. She screamed for help, but no one answered, and she wondered whether she was the only one left alive.

Raposa popped the release buckle and fell into the marsh, landing on her hands and knees. Her face burned from the jet fuel. She dug down into the black muck, cupped a double handful to her face and smeared it all over the affected areas. It seemed to help.

She looked into the distance, saw the dim lights of Miami framed against a coal-black horizon and noticed how far away it was. She was very scared, having never been in the Everglades before. With an injured back and a cut foot, she slogged through sucking muck, shredded saw grass and plane wreckage. She found a section of the cabin with a stewardess still strapped into her seat-belt harness. The flight attendant, Mercy Ruiz, was badly injured, with a broken pelvis and a severe laceration on her forehead.

Raposa did not have any blankets. She had no first-aid kit. She had nothing. But the passengers were her people—her responsibility—and it was still her job to help them. Serving coffee, tea and soda was all very nice, but this was what counted. With determination born of her Portuguese grandparents’ work ethic and her work on a 160-acre dairy farm as a young girl growing up in Rhode Island, the former Girl Scout troop leader shouted, “I’m a stewardess. If you hear my voice, come toward me. Follow my voice.” Within minutes, six to eight passengers crawled out of the dark and were seated on the scrap of flooring, shivering, afraid and in shock. In a weak voice, one of them asked, “What about the alligators?”

Raposa didn’t hesitate: “We made such a loud noise when we hit. I’m sure they all ran away.” She spit the words out quickly, doing her best to sound convincing. Ever the good Catholic, she crossed herself in the dark and silently prayed, “Oh God, please let that be true.”

A Coast Guard helicopter flew toward them, sweeping the marsh with a bright searchlight, and then turned away. Raposa’s survivors became upset. “They’re not going to find us,” an anxious passenger whispered.

“Yes, they are,” Raposa assured them. “The rescuers are picking people up from the nose section of the plane first. They’ll find us eventually.”

Raposa had the survivors scoot together, sitting back to back so they could stay warm. In a calm, soothing voice, she said, “Now close your eyes and pretend you have a cup of coffee, hot chocolate or tea in your hands. Picture that in your mind. That’s what you’re going to get when we get out of here. Now take a sip. Feel the warmth going down.”

The hours passed, and still no rescuers had arrived. Raposa was struggling for ideas to keep her group occupied. “Why don’t we sing to help warm ourselves up?” she suggested.

“What songs will we sing?” one passenger asked.

“Let’s sing Christmas carols,” Raposa replied. “How about we start with ‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’?”

DARK DISCOVERY

Ron Infantino woke up in a chill, heart pounding, breath erratic. In every direction, there was nothing but dead silence and incredible darkness. The cloak of black was made all the more intense by the surreal stillness. “My God, what do we do now? Am I the only one left alive?” he wondered.

Buried up to his neck in freezing water and muck, completely naked except for the elastic rims of his socks, severely injured, shivering and in shock, Infantino feebly called into the night: “Lilly, where are you? Help.”

Quiet.

Then a big, bold female voice reverberated somewhere out of the gloom, “Don’t anyone light a match!” A few minutes later, “If you can hear my voice, come to me! Follow my voice!”

But Infantino couldn’t follow the voice. He was trapped beneath the water. Unable to move and weak from severe loss of blood, his body hung suspended in the watery muck, still bent in the sitting position. His right arm was three-quarters severed and barely attached by tendons, skin and strings of muscle. His left knee was dislocated, wrenched sideways at a vicious right angle.

Oddly, he felt no pain. Shock had taken over.

An hour or so later, a Christmas carol floated through the air, reassuring Infantino he was not alone.

Five hours after the crash, the welcome sounds of voices and legs sloshing through water, labored breathing and flashlight beams probing the dark broke the silence. They were heading his way. “Please don’t leave me!” Infantino yelled.

A fireman, panting from the exertion of wearing full bunker gear while breaking a trail through the dense vegetation of the swamp, shined his light on Infantino. “Sir, don’t worry,” he said. “We’re not going to leave you.”

Two days later, Lilly Infantino was found trapped beneath one of the wings. Sadly, she did not survive.

SAFE AND SOUND

By about 3:15 a.m., Raposa’s flock of survivors had all been rescued. Now it was her turn. Retired Air Force Col. Frank Borman—a former astronaut, vice president of Eastern Airlines and now a first responder—came to escort her into a helicopter hovering at ground level a short distance away. He put his arm around her, and they began slogging through knee-deep muck and water. Suddenly, he stopped. “Wait a minute,” he said. “I lost my boot.”

“Well,” Raposa said, “I’ll help you find it.”

“No, I’m supposed to be helping you.”

“That’s okay,” Raposa said. “I’m a tough Portuguese girl from Rhode Island.”

HUMAN CANNON BALL

Around 4:30 a.m., Leonhard waded up to a willow head—a thick tangle of weepy trees with brittle limbs draping into the water. Leonhard discovered a hole in the bushes, roughly circular in shape and a little larger than the mouth of a culvert pipe. He probed it with his flashlight beam. Branches had been recently snapped off all the way around the opening, all pointing inward.

“I called out to a Coast Guardsman who was working nearby to come and help me out,” Leonhard said. “It looked like a piece of the wreckage, or something, had been propelled on a near horizontal trajectory, traveling just a foot or two above the water’s surface, and rocketed into the willows with tremendous force.”

Bent at the waist, the two men waded into the hole, following a ragged debris trail of damaged vegetation. “We went deeper and deeper, until we’d gone about 50 yards. Incredibly, we found a man sitting alone on a small tussock. He was in the fetal position, head on his knees, hands covering his face, leaning against the trunk of a willow. He had a broken arm and some cuts and scrapes, but no other visible wounds,” Leonhard said. “This guy had been hurled from the plane like a human cannonball. I wouldn’t be a bit surprised if the speed he’d been traveling was well over a hundred miles an hour.”

Leonhard added, “The guy weighed around 160, but it still took eight of us carrying a stretcher filled with his dead weight to carry him out. What made it so hard was trying to manhandle him up and over the broken willows. We had him out by 5:30 in the morning. I don’t know this for sure, but I seem to remember he was the last survivor rescued.”

Of the 176 passengers and crew members aboard Flight 401, 77 survived the initial crash. Two later died, leaving 75 survivors and 101 fatalities. Leonhard, Raposa, and Infantino never connected during the rescue operation, except for one tenuous bond that drew them together in spirit: the sound of a distant Christmas carol drifting through the night.

Adapted from Bad Guys, Bullets, and Boat Chases by Bob H. Lee. Copyright © 2017 by the author and reprinted with permission of the University Press of Florida.