by Kent Russell | May 2, 2017

Life Lessons From Behind-the-Scenes of a Miami Hotel

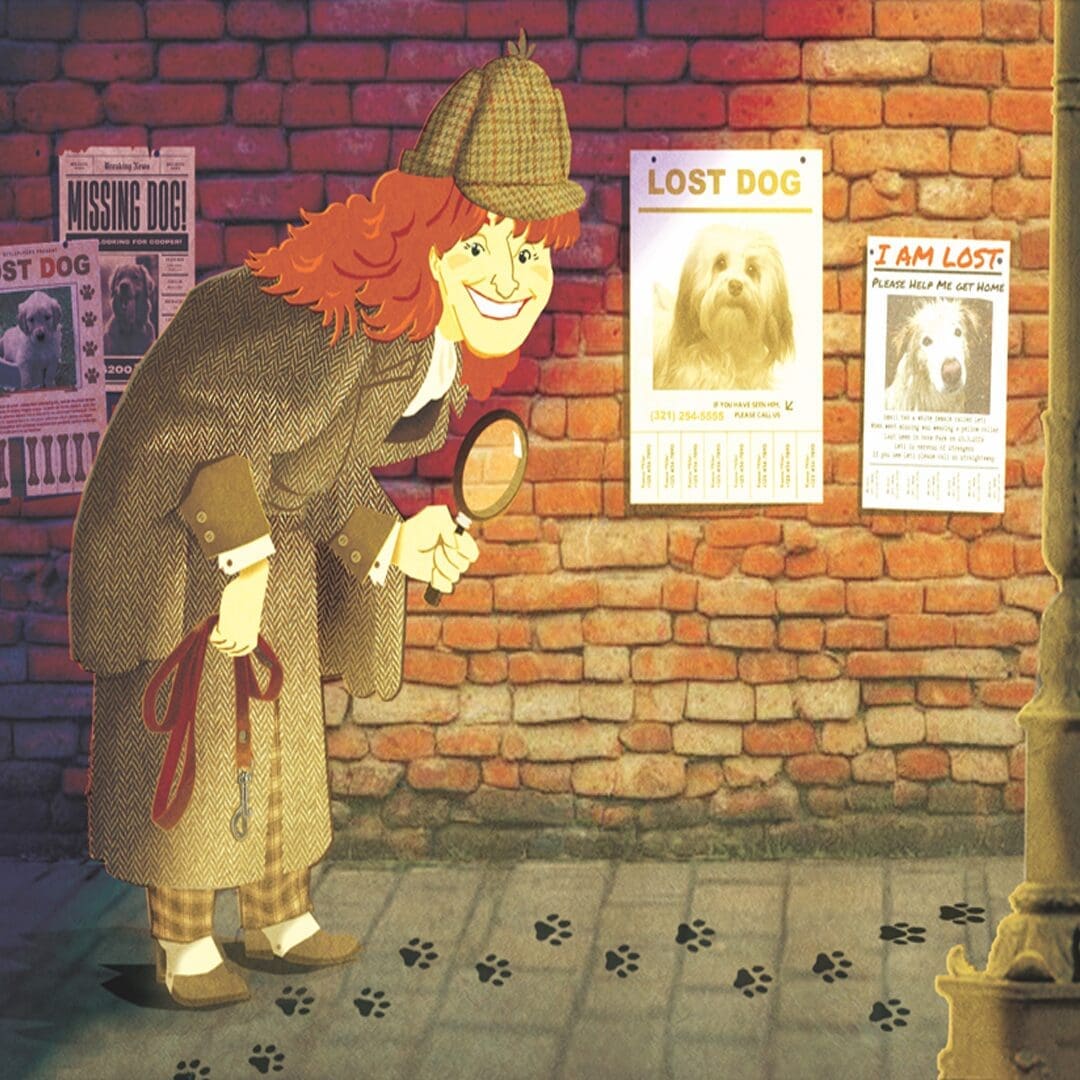

This Eloise meets Dennis the Menace reverie in a South Miami hotel taught this writer everything he ever needed to know

Friday afternoons in Miami, right as schools let out, were when the city felt most alive to me, the most itself. Suddenly into the sluggishness of the siesta hour spilled public, private and parochial schoolkids and their parents, a swarm that thronged the sidewalks and choked the thoroughfares. Black, white, Cuban, Nicaraguan, Haitian—rich, poor, middle class—the whole plurality of cultures that made up ‘90s Miami slid by and between one another like shuffled cards.

When the clock struck 2:45, I would emerge from the second-grade classroom of my Coconut Grove elementary school with my best friend, Filipe. The two of us had met in the prekindergarten program. In fact, we had met on the first day of school: As soon as my mother peeled the last of my fingers from the door frame, I hustled past the other kids, who were pretending to eat a dead palmetto bug with plastic forks and knives. I spotted a small, dark, quiet boy sitting alone at the back of the classroom. His hooded eyes and immaculately parted black hair lent him the air of a telenovela scoundrel, a miniature one. I thought then: You! You will be my friend! I took the seat next to his. Turned out, he didn’t speak a word of English. Turned out, his family had just moved here from Brazil.

Years later, in the parking lot after school, the two of us would shield our eyes against the golden grout of sunlight burning through the Grove’s overhanging fronds. We would walk to the rear of the lot, where one of the valets from the Hotel Villa would be leaning against the company van, his arms folded.

Though they’d been civil engineers in Brazil, Filipe’s parents were turned into hotel managers by the time their plane touched down in Miami. Some friends of theirs had opened the Villa; these friends quickly realized that they needed smart, responsible, trustworthy people to run the joint.

Their hotel had upscale pretensions. It was marketed to the newly moneyed Latin Americans who were pouring into Miami at the time. It only made sense that the Villa be guided by similarly striving hands.

The drivers who picked up me and Filipe on Fridays tended to be young Brazilian men with artful stubble and polarized aviator shades. They didn’t talk much as we flew past the pseudo Arab minarets, the mock Andalusian towers and the “Venetian” palaces of Miami’s outlying municipalities.

Without fail, these valets would tune the radio to 96.5 FM, Power 96. DJ Laz, who scored all of my generation’s roller rink birthdays and awkward middle school dances, would be doing right by the city on the wheels of steel.

The Villa was located in not-quite-picturesque South Miami. The photos on the brochure were cleverly cropped, so as to exclude the grim parking garage and the hospital complex that bracketed either side. The brochure also neglected to mention that the Villa was seeded among a field of auto repair shops and vacant warehouses. It was a good hour away from any sandy beach. Its closest tourist attractions were Shorty’s Bar-B-Q and a criminally underlit Metrorail station.

The hotel itself was something of a pink-and-beige fortress, six stories tall. Our drivers would pull up to its cement and stucco facade and slide open the white van’s door with nary a word. Filipe and I would bound between royal palms on our way into the marbled lobby. We’d make a beeline for the smoky, windowless back office, where we’d plant kisses on both sides of Filipe’s mom’s face and shake hands with his dad. Then, they’d give us free rein over the hotel grounds until their day’s business was done.

First, we would doff our shoes in the office before running into the lobby, sliding on our sockfeet Risky Business-style past a clutch of South American tourists wearing puzzled expressions on their swiveling heads. Where was South Beach? their furrowed brows would seem to wonder. Where was the building with the square cut out of it? Where was Crockett and/or Tubbs?

Next, Filipe and I would program a key to a room on the third or fourth floor. There, we’d turn down the window unit as low as it could go. We’d watch risqué TV. We’d order hamburgers from room service, free of charge. We’d jump from bed to bed, we’d wrestle on the carpet, we’d never once consider the mondo protozoa that would’ve shone as if they were bioluminescent had we wanded a blacklight over any one surface. Bored after this, we’d go down to the pool in the center of the Villa’s atrium and have ourselves a thrashing noodle fight. Sometimes, there would be a couple attempting an exchange of vows in front of the pool’s waterfall. Sometimes, there would be an enraged father of the bride who’d chase us out of the pool and into the laundry hallway, where we’d make our getaway through clouds of dryer steam.

For many years, these Friday afternoons were my idea of paradise. A kind of Eloise meets Dennis the Menace reverie. As Filipe and I entered high school, though, we became less and less interested in the juvenile pleasures of the hotel. We began hanging around the employees. The valets who picked us up from school, the bartenders who unboxed crate after crate of dark rum, the laundresses who tittered brightly, the line cooks who’d forsworn their unsavory pasts.

Sitting on a folding chair in the valet hut or kicking my heels against a chest freezer in the kitchen, I came to understand that I was backstage. I was behind the curtain. Watching how the employees worked, how they behaved around guests, I came to understand that their self-presentation had less to do with who they were than whom the guests wanted them to be. I was among the minimum-wage wizards, the people who might have been professors or white-collar professionals in their homelands but here, in Miami, were those who conjured the fantasy that visitors came for.

Filipe and I loved it. Backstage, the employees would talk to us in a manner they’d never dare to use with the guests or with Filipe’s parents. There were baroque Spanglish swears. Thrilling yet unprintable insults. A style of roughhousing that stopped just short of assault. Overall, though, Filipe and I were treated as if we were junior workers, apprentices. It was almost as if the employees were initiating us into the front-of-the-house guild. They taught us how to create a persona. How to read an audience. How to excite the imagination and satisfy desires people didn’t even know they had.

There was a bond in those backstage areas, a bond born of people who were working together to sell an idealized experience. This bond cut across the staff’s ethnic and socioeconomic divides. I still miss this bond, even though Filipe’s folks have long since quit the Villa. In the intervening years, the hotel has changed hands a few times and drifted down-market. Currently, it operates as part of a national chain. It earns Trip Advisor reviews such as: “Run away!! Run away fast!!”

Filipe and I still hang out on Friday afternoons. It’s just that nowadays, we’re meeting in New York City, where we’ve relocated for work. He’s become an investment banker; I’ve become a writer. Sometimes I wonder how our career paths could have diverged so dramatically. But then I think back to those evenings spent in crowded break rooms and banquet halls post-buffet. I think back to the perpetual motion, the ceaseless self-reinvention, the service with a smile. Thinking back, I see that Filipe and I are who we are because of the education we received, the training. Regardless of whether we were destined for the boardroom or the back room, the trading floor or the page, ours was the best education—the most Miami education—any schoolkid could’ve asked for.