by Eric Barton | May 22, 2025

The Return of Florida’s Roadside Motor Lodges and Retro Motels

The boom and bust story of Florida's roadside motor lodges and how retro motels are sparking a new urban renaissance.

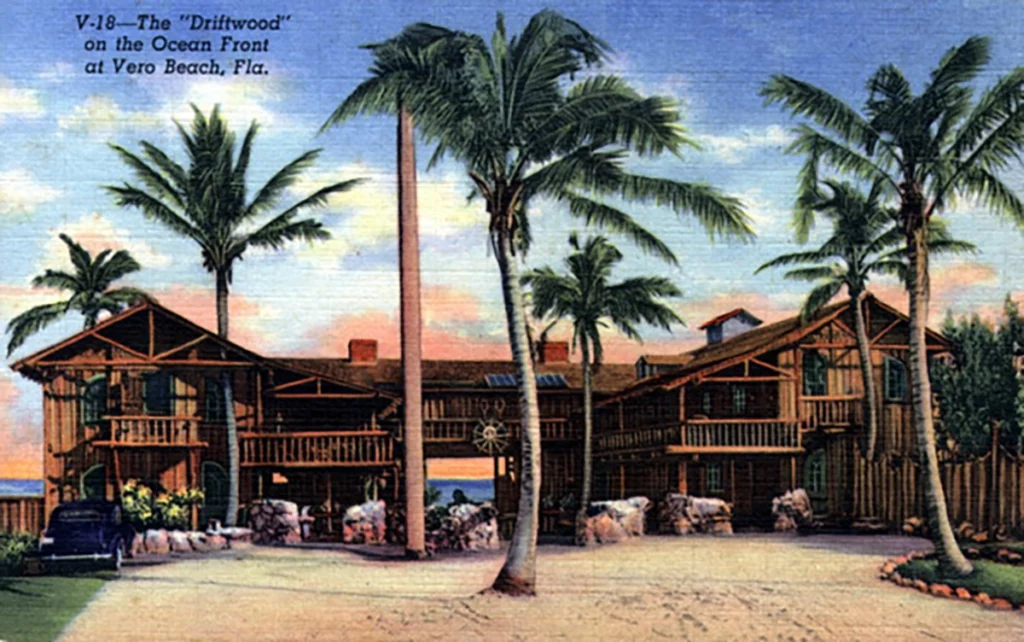

Lynn Acor was 15 when she started as a bellhop at a kitschy roadside motel on the beach in Vero—the Driftwood Inn. She’d park a guest’s car and then pretend to struggle with their bags for extra tips. Back then, in 1985, she called it Zero Beach because there wasn’t anything for a teenager to do. But she immediately loved the Driftwood.

It’s fair to say the motel’s first owner was eccentric. Waldo E. Sexton built the original building out of slash pine and pecky cypress. Faded to gray, it now looks like the detritus washed ashore from a shipwreck.

Now known as the Historic Driftwood Resort, the property includes several buildings and oddities. At one time there was “Waldo’s Mountain,” a mound of dirt piled up on the property after dredging the Intracoastal, and according to author Sean Sexton, grandson of the hotel’s founder, “the second-highest point between Key West and Kitty Hawk.” He filled the lobby with a statue found in a Madrid attic, a 700-year-old wedding chest from Persia and a quirky 250-year-old painting from Italy.

Acor loved it and still does today. She moved away from Vero, lived in eight states and two countries. Next, she married the son of Vero’s then-mayor, finally moving back in 1996 to raise their two daughters. Twenty-seven years after her first day as a bellhop, Acor took a job again at the Driftwood in 2012, and she’s spent the past 13 years working at the front desk. Just as it was back then, there are no

computers to help run things—just a hand-written ledger for tracking bookings.

“Oh, this place is my everything,” Acor says with a laugh, although I suspect it may not be a joke. “But I’m a weirdo. Everyone knows this here. I’m also a widow, and people joke that I’m in love with two dead people.” Just to be clear, they’re talking about her late husband as the first and her fellow weirdo, builder of the Driftwood, Waldo E. Sexton as the second.

Read the timeline of Florida’s retro motel boom and the history of the Vagabond Hotel Miami.

Perhaps it would seem odd to some of us to be smitten with the late builder of an eclectic motel. Or similarly to be in love with the Driftwood itself. But old motor lodges like the Driftwood helped build Florida. They sat as welcome signs for upstart cities, they waited at every interstate exit, and they were the lighter’s spark on the Roman candle of the Sunshine State’s first tourism boom. For the nostalgic, it can be easy to love old motels themed like high school dances—which is why some with a more adventurous spirit have begun renovating historic motels in an attempt to recreate every meretricious detail.

Why, you might be wondering, would people care about these two-bit buildings that, in your own town, might still serve as by-the-hour fleabags? I had suspected the answer might simply be that the places make business sense. But the answer is more than that: It’s about how these places helped make Florida what it is today.

The Era of Kitsch

For all of Tracy Revels’s life, the roadside motels along U.S. Highway 90 stood as totems of the passage of time, like yellowing family portraits on the mantle.

When she was young, after her parents split up, Revels would be the passenger as they drove her between the Madison tobacco farm where she was raised and the place where her father lived in Jacksonville. The old motor lodges served as guideposts to how close she was to home: the Hawkins Motel in Baldwin, the Sands Motel in Lake City and, getting close now, the Sunshine Inn in Live Oak. “Highway 90 is a pretty drive,” Revels says, “if you’re not in a hurry.”

Those old motels began to fade. When Revels enrolled at Florida State University, she found herself traveling on 90 again between home and school, where she eventually earned her doctorate in history. From her car window, she’d watch the hospitality relics roll by with trees growing out of windows and plywood nailed over doors. Revels moved away from Florida to take a job as a professor in the

history department at Wofford College in Spartanburg, S.C. Those empty boarded-up inns faded from her memory just like old work friends did.

I realized right there—people have an emotional connection to these places. And it was something I needed to research.

—Tracy Revels

In the early aughts, Revels attended a history conference in Daytona as part of a panel of three experts. While talking about her fascination with “the gaudy age of Florida tourism,” something odd happened. People in the audience kept raising their hands at the end to tell her stories about the old roadside Florida motels where they used to vacation. “It was so weird,” she says. “I realized right there—people have an emotional connection to these places. And it was something I needed to research.”

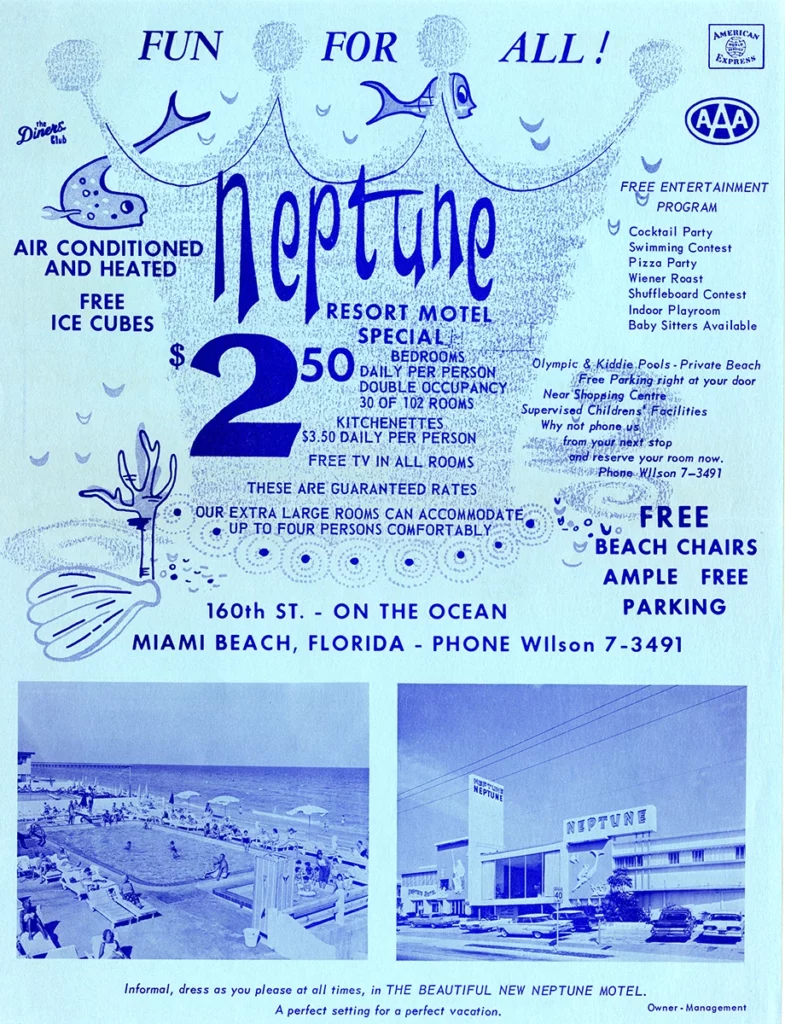

She spent years working on her next book, “Sunshine Paradise: A History of Florida Tourism.” What she learned in the process was that roadside motels tell the story of the growth of Florida. It begins back in the era of Henry Flagler, who built grand hotels along his railroad, lavish places out of reach for almost everyone. Then came the automobile and interstate highways, which brought G.I.s who trained in Florida and wanted to drive their families here for vacations. In the beginning, travelers stayed in motor courts, which are essentially drive-in-style campground destinations. But then came roadside motels that allowed people to park their cars right in front of their room. The motels advertised window AC units and sported kidney-shaped pools. They drew families in with schlocky attractions attached to the hotels. “They were on their way to the beach, but they were willing to wander and see all these little Monkey Gardens and Sunken Gardens and Weeki Wachee and Silver Springs,” Revels says. The people arriving in those big, hulking American cars had a nickname: “Tin-Can” tourists, a reference to the popular Ford Model T they drove.

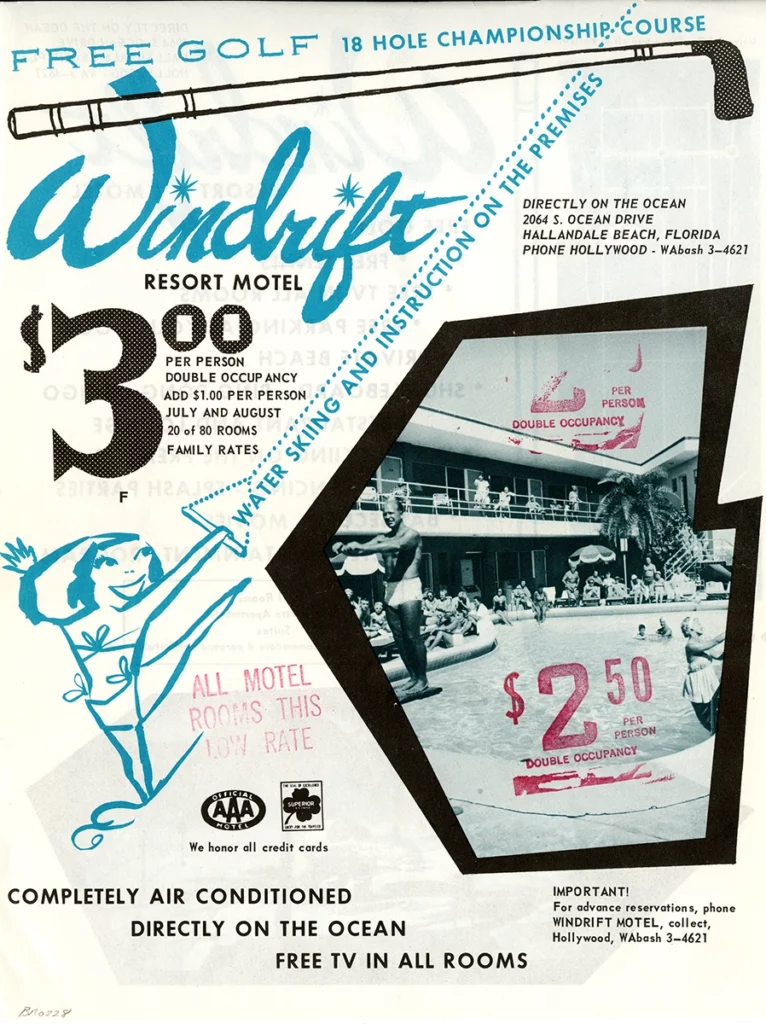

The building style of these motels might look utilitarian to some, like places solely designed around the car. But these flat-roofed, squat structures—often no higher than two stories—followed a generic floor plan template with guest rooms that opened toward a parking lot, says Anthony Abbate, architecture professor at Florida Atlantic University. The roadside motels would take architectural cues from the cities around them, adding Spanish-Mediterranean, midcentury modern or art deco flourishes. They’d sprout beacons and lighthouses above the lobbies. Often they’d incorporate intricate signs directly on the building. They’d stand out from neighboring competitors with attention-grabbing, bright signage or themes: the Polynesian Inn in St. Cloud, the Neptune Hollywood Beach Hotel on Hollywood Beach and the Seabreeze Inn in Fort Walton. “It’s a time when Americans were adventurous and really exploring the country easily for the first time,” Abbate says. “These places, they felt like adventures.”

You know what comes next. Big, boxy chain hotels arrived, though not on the side of highways. Instead, these new hotels sprouted from the sand, favoring the smell of the ocean rather than exhaust. The old motels mostly became by-the-hour flophouses. But then came a new appreciation for nostalgia.

Checking In

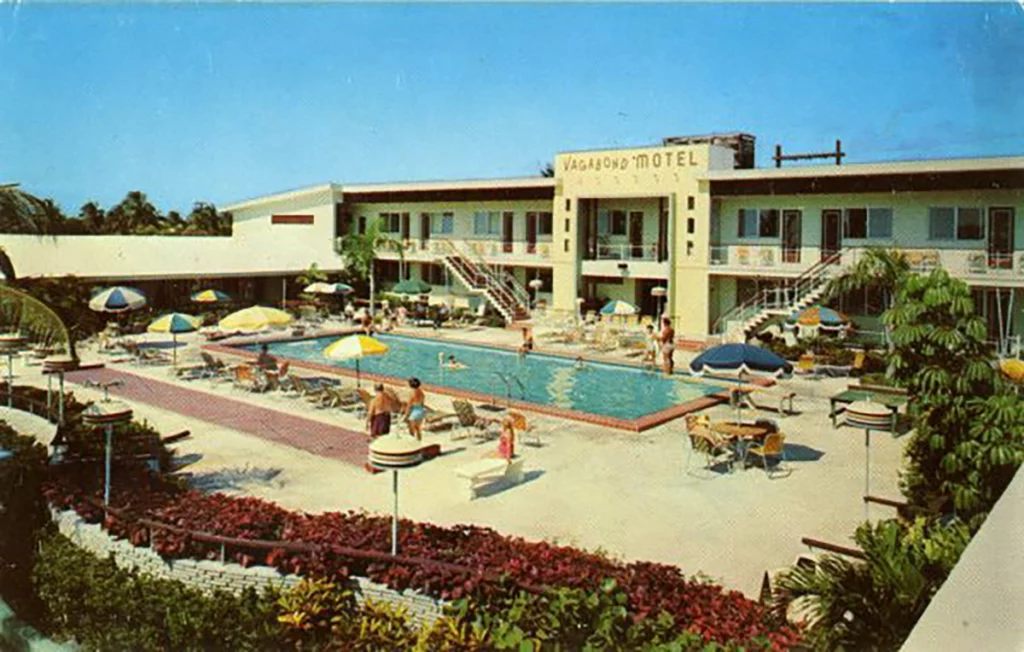

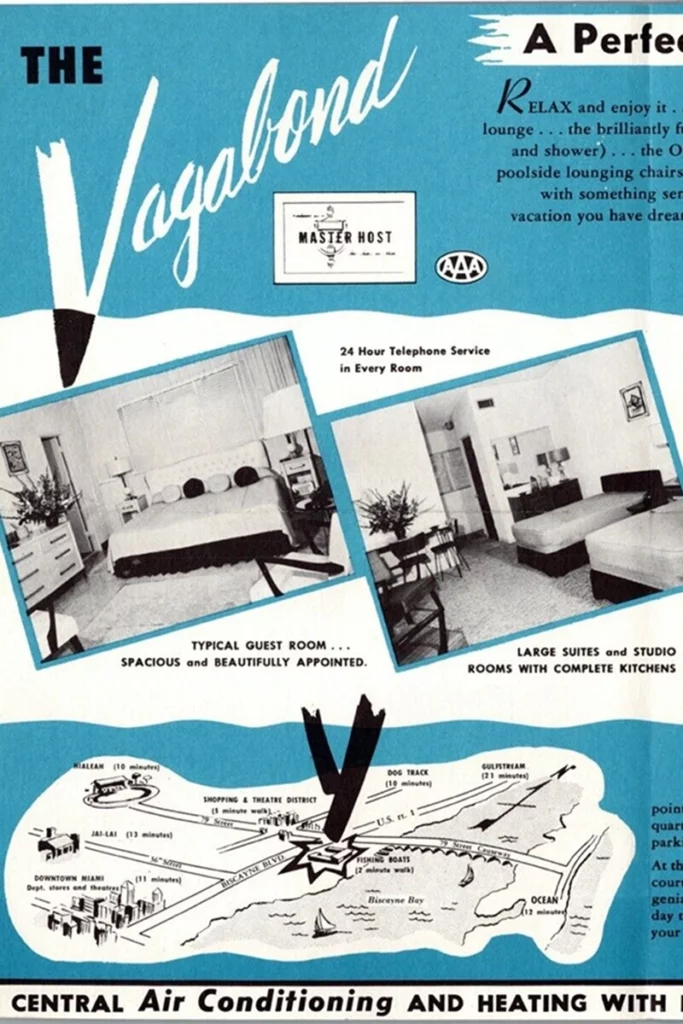

Most cities in Florida had roadside motels along the corridor that led downtown, but nowhere is this highway of hospitality more obvious than in Miami. These vintage outposts dotted Biscayne Boulevard in bright neon for Selina Gold Dust, King Motel, Leeward Motel and the Vagabond Motel.

Billie Myers remembers being dazzled by all of their glowing signage and art deco details when she first came here from her hometown of Coventry, England. “In England, it’s all centuries-old buildings that are mostly decaying,” she says. “Then you come to Miami, and there’s a brightness and optimism.” This was the late ’90s, and Myers planned to stay two weeks but eventually ended up making Miami her home. “Florida is so incredibly different. It’s bizarre, really,” she says.

Myers worked for hotels, helping open and run them—usually massive resort properties. So it was a bit odd when Wall Street bond trader Avra Jain called her in 2013 and asked if Myers would come work at what is now known as The Vagabond Hotel Miami. The place had sat behind a fence for years, windows missing, a filled-in pool, wounds in the roof, foliage overgrown. But Myers saw a challenge in it all—a challenge to give new life to something once beautiful.

Jain assembled a team and invested around $8 million into purchasing and restoring the property, which reopened in 2014 to much fanfare. The rooms are outfitted with midcentury-style murals and plush Italian mattresses. Around the pool, teal umbrellas shade bright orange loungers, all surrounded by lush tropical vegetation. The setting evokes a Space Age period film set. Over the past decade, the revamped Vagabond has drawn celebrities like Pitbull to film music videos, chic Miamians to throw glitzy poolside parties and acclaimed chefs to open restaurants on the property. Most recently, the bar and dining area became home to Ensenada—a buzzy Mexican seafood hot-spot.

The Vagabond turned into a beacon again. Its blue neon sign lights up a potential turn-around for the whole neighborhood, which is now referred to as MiMo—one of those rebrandings developers do to make a once-neglected neighborhood seem cool again. The Vagabond isn’t alone in the annals of old motels brought back to life in Florida. Naples designer and developer Kristen Williams purchased The Gondolier Inn in 2018, bringing it back to its pink-hued glory. The Beachside Hotel & Suites in Cocoa Beach spent over 10 months undergoing a $5.9 million reno in 2020 that brought out its multihued charm. In 2021, Leila and Adam Bedoian reopened The Local in St. Augustine and then earned the honor of “Best Roadside Motel” in America by USA Today.

Americans were really exploring the country easily for the first time.

—Anthony Abbate

Less than a year after The Vagabond reopened, restaurateur Ani Meinhold found herself literally confronting ghosts at the Sir Williams Hotel in Miami. Meinhold grew up in Puerto Rico and New York, came to Miami for college, and has been here 23 years now. I asked her if she ever stayed in the roadside motels along Biscayne during her visits to Florida: “What? No. Absolutely not. No.” They were places she associated with women walking the street in front of them and those less fortunate sleeping under the motel overhangs. They were not places to vacation, not anymore.

The Vagabond’s renovation kicked off a string of similar projects along the Biscayne corridor. In 2015, Meinhold opened Phuc Yea, which she describes as a “modern Vietnamese mash-up.” The restaurant took over the space that once was the Sir William Hotel lobby, serving cod lacquered in Chinese barbecue sauce and bao buns with caviar. In 2022, The Michelin Guide gave it a Bib Gourmand award, which they’ve now won four years in a row, and the quirky restaurant suddenly became a place, not just for locals, but for out-of-towners too. Michelin explains the vibe: “A nearby table might launch into song. You are welcome to join the fun.”

Sometimes, there are also uninvited guests at the restaurant. People spot a woman smoking in an upstairs window, a former room in the Sir William Hotel. It’ll smell of cigarettes up there, too, even though, as far as anyone knows, nobody’s been smoking. “You can,” Meinhold pauses, “feel the spirits. They’re not bad. As humans, I think we can just sense these things. But you can just feel that there’s something. I believe she’s a kind one—a protector of sorts. Nothing spooky or negative—just a quiet, watching energy that keeps us on our toes.”

The smoking woman in the window is seemingly like a symbol of the old roadside motels, once so full of life and optimism. The iconic motels were symbols of Florida’s comeuppance. Then, the motels haunted our towns, shuttered and ugly and sometimes housed humanity’s darkest shadows. But finally, here and there, the motels have been renovated back to their former glory, to the way they appeared in postcards—symbols, in neon and pastels and kitschy themes, of something new and exciting.