by Jessica Giles | June 23, 2021

Preaching The Bob Ross Gospel in New Smyrna Beach

How the legacy of famous PBS painter Bob Ross lives on in a New Smyrna Beach strip mall

The moment Nicholas Hankins’ feet hit the driveway after school, the race began.

The 11-year-old wasn’t hightailing it to meet his friends at the basketball courts or fire up his Nintendo, instead he’d rush inside his two-story home nestled in the woods of Greenville, Tennessee to grab his paint supplies.

There was no time for the lanky preteen to change out of his school clothes, so he’d just do his best not to splatter any paint on his T-shirt and jeans (the same couldn’t be said for his parents’ carpet). With a canvas, brushes and paint tubes in hand, Hankins would barrel down the steps to the basement, where the brown shag carpet was most forgiving. His mother relegated his artistic expressions there the moment he brought home the painting kit.

As the hour hand inched toward 3 p.m., Hankins would frantically lay out his supplies in front of the television, hoping to beat the buzzer: the first jazzy chords of Bob Ross’s The Joy of Painting theme song.

If Ross decided to start with a black canvas, Hankins was out of luck.

The budding artist did his best to follow along with each crisscross stroke and happy cloud, but this was before the days of TiVo so it wasn’t long before Ross lost him. Never discouraged, the aspiring painter just made up the rest as he went.

After the program ended, he’d march upstairs to show his parents his masterpiece. As soon as he flipped it around, his mother would drown him in praise.

“Oh it’s so beautiful!” she’d exclaim—before she noticed the paint all over the carpet. Meanwhile, his father would sit in silence, his index finger resting on his lip, eyes squinted. For three or four minutes the air would grow heavy with expectation, until finally his father would say, “What if…” and offered a suggestion. Always “What if….”

I’m so thankful Dad gave me the kind of feedback he did about my paintings early on because he would never let me get too inflated or deflated.

— Nicholas Hankins

It aggravated Hankins. Every weighty silence always followed by a correction. Couldn’t he just congratulate him on a job well done like his mother? But as Hankins got older, and his pile of Bob Ross imitations grew larger, his dad’s response began to change. Three minutes of silence became two. Sometimes his suggestions were preceded by a compliment.

“I’m so thankful Dad gave me the kind of feedback he did about my paintings early on because he would never let me get too inflated or deflated,” Hankins recalls.

He gets his creative genes, in part, from his father, whose intricate ink drawings of old, weathered buildings hung in their home for as long as Hankins can remember. For many years, he didn’t even realize his father drew them. He was too young to read the signature on the bottom.

One day, Hankins finally asked his mother where the artwork came from. “Oh, your father did those,” she said. Hankins’ eyes widened. He begged his dad to teach him.

Now 39, Hankins has upgraded from his parents’ basement to the very studio that Bob Ross founded in a small Florida beach town. There, without fanfare, Ross’s legacy lives on through art classes and instructor training and a little-known but impressive display of his works. A space for people to test what Ross had always believed: anyone can be a painter. And it’s Hankins’ job to make them believe it.

The Birth of Bob’s Workshop

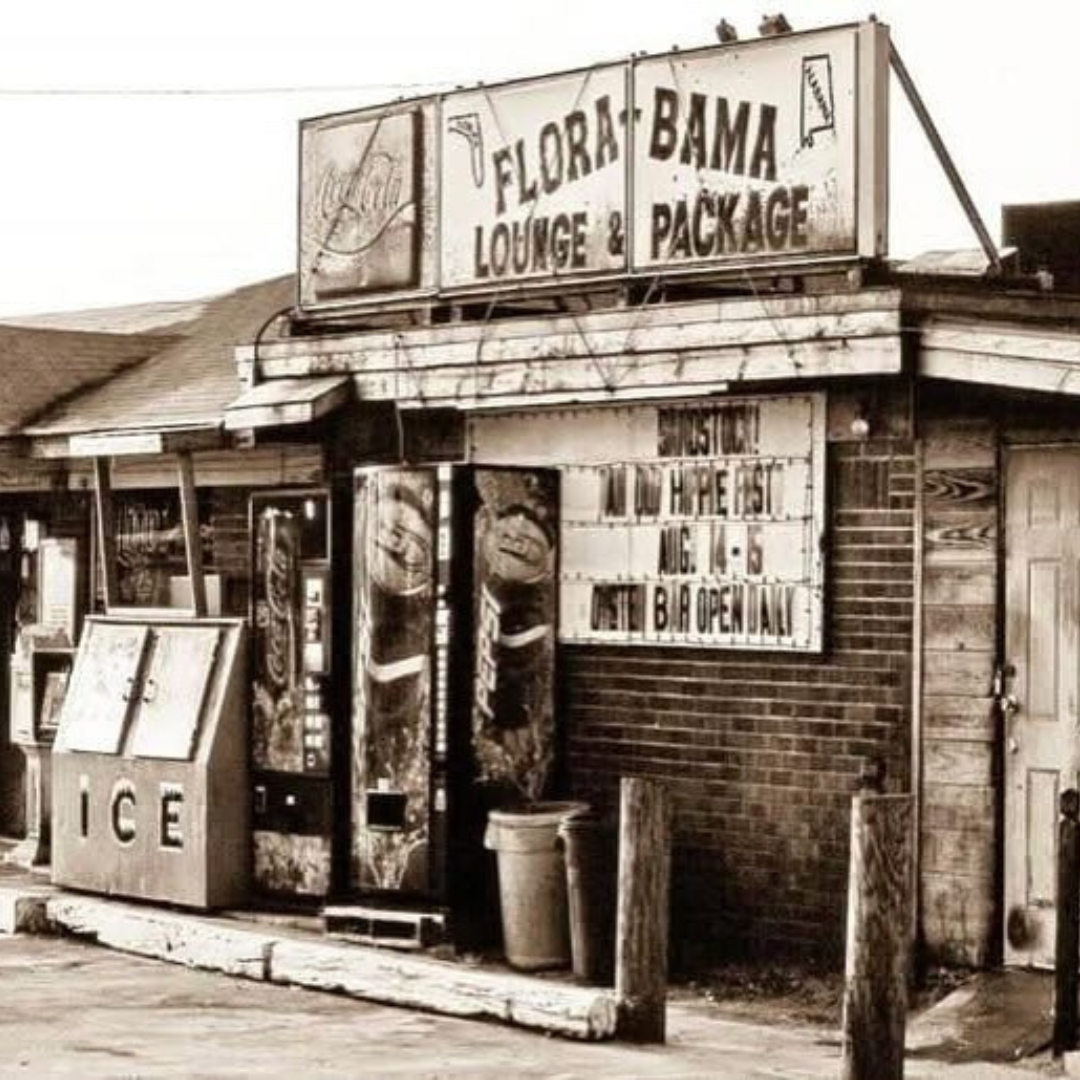

There’s no neon sign or billboard letting you know you’re close. In fact, it’s difficult to spot the little studio behind the Twistee Treat towering in front of it. But there, in a New Smyrna Beach strip mall, sandwiched between a dentist’s office and a sushi restaurant, sits the Bob Ross Art Workshop & Gallery.

Ross was born just up the coast in Daytona Beach and raised in Orlando. Following his service in the U.S. Air Force where he took his first painting class, Ross returned to the Sunshine State, bouncing between Orlando and New Smyrna Beach. He opened the gallery himself in 1992, but it wasn’t without prodding. In fact, the tale has become a sort of folklore passed down throughout Bob Ross Inc. Annette and Walt Kowalski, who were business partners with Ross back when his star was first rising, owned a condo in New Smyrna Beach near the strip mall. One day, Annette ran into the nearby Publix to grab some supplies for a barbecue when she spotted the empty storefront, just the right size for an art studio.

“Wouldn’t it be so nice to have a place to display some of your paintings?” She asked Ross. “A place to teach some classes? You should really think about it,” she pressed. But Ross resisted. He always did have a case of wanderlust, preferring to travel and teach rather than put down roots.

So Annette played to his weakness: Dustin’s Bar-B-Q.

She took him to a barbecue dinner at his favorite restaurant and stuffed a few tissues in her purse in case she needed to unleash the waterworks. Eventually, after a heaping pile of pulled pork and Annette’s smooth talking, she convinced him.

You’d never guess that 54 Bob Ross originals are nestled among this unassuming cluster of shops off of A1A, but Hankins, now the manager of the studio, is pretty sure that’s exactly how Ross would’ve wanted it. No pomp and circumstance, just a humble spot to display some of his bubbling brooks and teach a class or two.

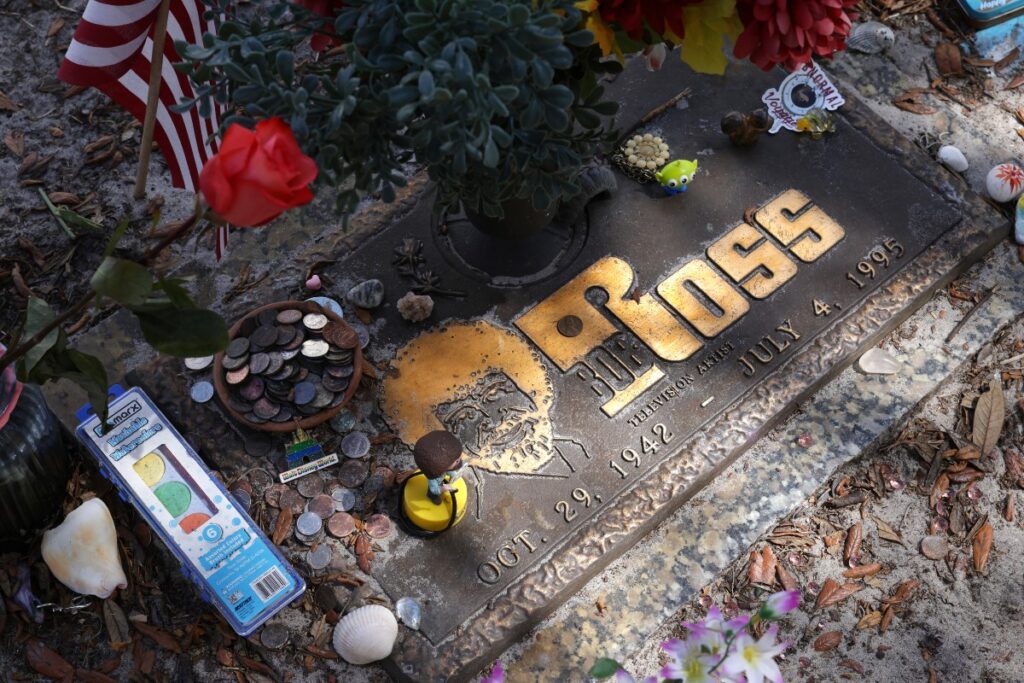

Ross died of Lymphoma in 1995, three years after opening the studio, and his popularity only continued to climb. When the video game streaming platform Twitch aired a marathon of The Joy of Painting in 2015, a whole new generation fell in love with Ross’s hypnotic voice and calming technique. A visit to his gravesite in Gotha, Florida reveals just how beloved this television painter was. His tombstone is adorned with watercolor sets, bobbleheads, happy little tree mints, easels, animal keychains and paintings that people have left there.

Today, the Bob Ross Art Workshop & Gallery stands as a testament to his Florida roots. Until 2020, it was the only place in the world where Ross’s artwork was displayed year-round. Now, it’s one of two, joined by the Bob Ross Experience in Muncie, Indiana, an interactive museum in the same house where Ross filmed The Joy of Painting. There, you’ll find Ross’s original paintbrushes, palette and paintings encased in glass. Even the trash can he used to beat the devil out of his brushes sports a plaque explaining its significance.

Not at the New Smyrna gallery. Here, Ross artifacts hang around almost haphazardly. Nearly every square inch of the purple-hued walls are filled with Bob Ross originals, and you can walk right in to admire them—no ticket required. Aquamarine light filters through the fairy-like forest onto a babbling brook in “Forest River.” Streaks of purple and pink dance above the tree line dusted with snow in “Twilight Beauty.” When people mosey in off the street, they almost always recognize the large painting hanging on the left wall. It’s an untitled piece featuring a majestic mountain and Hankin’s personal favorite in the shop.

“That’s the one I saw him do on TV!” the visitors always say. Hankins can’t help but laugh. It’s the only one on the wall that never appeared on the show.

And it’s not just Bob Ross originals. Annette Kowalski and Bob’s son, Steve Ross, also have original artwork displayed at the New Smyrna Beach workshop. If you ask nicely, Hankins will fish out more Steve Ross paintings from the back, even though touching them makes him nervous. Oh, and you’ll undoubtedly stroll right past Ross’s easel, which still stands at the front of the classroom like he just stepped away from it a moment ago to take a break. Hankins uses it when he teaches—no pressure.

Beyond being a low-profile haven for Ross’s artwork, it’s also the only place in the world where you can become a Bob Ross Certified painting instructor. Sure, anyone can follow Ross’s tutorials to paint like him, but if you want to use his branding and teach official Bob Ross painting classes with the blessing of his corporation, you’ll have to become certified.

Back in 1993, Hankins’ ears had perked right up the moment he heard Ross mention the certification on his show. While most of his fellow 11 year olds dreamed of being police officers or veterinarians, all Hankins wanted to be was a Bob Ross instructor, so he began the hunt for a teacher in his area.

“People kind of discover that you’re interested in something and then the word travels,” he said. “I felt like there was a little network of people in this little town I grew up in that knew this was something I was intensely interested in and were always on the lookout.”

A family friend called up his dad to let him know that a traveling Bob Ross teacher would be leading a class at her local art studio. Hankins signed up immediately. If he wasn’t bitten by the Bob bug yet, he certainly was after that first in-person class. By age 16, Hankins wanted nothing more than a Bob Ross instructor certification, but he didn’t quite have the disposable income—or the wheels—to get to New Smyrna Beach. Instead, he opted for a different certification, one that was close in proximity and practice to the Bob Ross method: the famous painter’s mentor, Bill Alexander.

Alexander was the one who taught Ross the wet-on-wet technique and how to complete an entire landscape painting in under 30 minutes. In fact, he was even the first to do this on television, leading people through 28-minute landscape paintings on his show, The Magic of Oil Painting. But while Alexander may have been the one to hone Ross’s craft, his persona was entirely distinct. Alexander took a more jubilant approach to art, his thick German accent crescendoing with excitement as he encouraged his viewers to “fire into” the painting and tap into their “almighty imagination.”

Ross’s disposition couldn’t have been more opposite. His soothing voice rarely rose above a whisper, and yet, it only made people lean in and listen closer. Hankins’ Alexander certification gave him the knowledge he needed to begin teaching classes, but it wasn’t just the skill he was after. He wanted to learn how to give people that feeling that Ross gave him when he painted, to make anyone believe that they were capable of creating a masterpiece, even if they’d never picked up a paint brush.

Some say that can’t be taught. You can learn how to explain the method, demonstrate how to hold the painting knife and maybe even throw in a Bob-ism or two. In fact, Hankins learned all those things when he finally earned his certification at the New Smyrna Beach gallery in July of 2011. But you can’t mimic the feeling; that was just the magic of Ross, and it’s part of what cemented him as a pop culture icon long after his show stopped airing on PBS in 1994.

That’s when I discovered the power of Bob. I had more work than I could do.

— Nicholas Hankins

With a Bob Ross certification in hand, Hankins could finally start teaching true Ross classes with the painter’s brand. As soon as he started putting that signature afro on his class advertisements, his phone didn’t stop ringing. “That’s when I discovered the power of Bob,” he said. “I had more work than I could do.”

He stepped away from his full-time job in finance to pursue what he’d dreamed of since he was splattering paint all over his parents’ carpet. “Thanks to Bob,” Hankins said. “He laid the groundwork and had done all the hard work of establishing a brand, advertising, and I just kind of jumped on his coattails.”

He began traveling all over the country to teach Ross classes to eager artists. He spread the grosspel from North Carolina to Florida to Houston to Las Vegas. When Hankins went down to the New Smyrna Beach gallery in 2018 to teach a few classes, the then-manager called him back into his office. “So, you wanna take over the workshop?” the manager asked casually. Sometimes, Hankins still has to pinch himself.

Teaching the Grosspel

Hankins moved to the Sunshine State in January 2019 to helm the workshop alongside his wife, Ada. She’s an artist herself, and Hankins swears he warned her long ago what she was getting into. Even before their first date, Hankins sat her down to explain that there was someone else who had his heart: Bob. Now Ada jokes that when she married Hankins, she married Bob, too. You can tell by the way she beams at Hankins while he teaches or when she helps someone perfect their snowcapped mountains that she doesn’t mind all that much. She once spent three days trying to buy Nic an exact replica of the medallion Ross wore around his neck. She only gave up when she learned that the medallion was made out of a gold kruggerand, a type of South African currency, and she’d have to shell out more than $1,000 for one.

Hankins doesn’t really need the medallion to embody Bob anyway, it’s happened naturally, even if he doesn’t like to admit it.

As he leads a class of seven Ross instructor hopefuls, Hankins teases Bob and his sayings. “Today we’re painting Happy Majestic Whatever,” he laughs. He prefers to just call them by their numbers: painting 1403 or 1608.

Despite poking fun at Bob’s tendency to transform everything into a “happy majestic something,” Hankins unintentionally teaches his class with the same childlike persona that Bob did, instructing people to start a little cloud in the corner of their canvas and insisting that sound effects aid in the painting process. He lets out a whoosh like rushing wind as he layers on his northern lights. “I always imagined it sounded more like a lightsaber,” one student pipes up, demonstrating his own sound effect. Soon the classroom is filled with swooshes, whizzes and shhhs as everyone tries out their own sound effects.

Hankins measures each dollop of paint in candy sizes: a Hershey’s Kiss of Prussian Blue, an M&M of Sap Green and a chocolate chip of Mountain Mixture. He slathers the paint on his canvas in a way that would appear aimless, if it weren’t for the detailed description he offers at every step. His knowledge of Ross’s method and portfolio are encyclopedic.

“This episode appears before Bob had liquid white,” Hankins says about the “Northern Lights” painting they’re working on this afternoon. The instructor can tell you in what order Bob mixed his colors, at what angle he held his painting knife and even what episode the painting appeared in.

“I think Bob has just taken over a part of my psyche,” Hankins jokes.

Some say his voice even sounds like the late painter’s.

“Yeah I’ve heard people say that before,” he chuckles. “I don’t hear it.”

There’s no denying that his artwork is a spitting image of Ross’s. If it weren’t for his signature in the bottom left hand corner, Hankins could probably fool some unsuspecting eBay customers into thinking it’s a Ross original, although he would never dream of it. He sells them on his own website, some going for more than $1,500.

I think Bob has just taken over a part of my psyche.

— Nicholas Hankins

He never pursued his love of Ross in the hopes of becoming a millionaire. He does it for that indescribable feeling. The one that first welled up inside him at 11 years old when he rushed to lay out his supplies to follow along with Bob on The Joy of Painting. The same one he sees plastered on his students’ faces when they finally speckle their mountain with just the right amount of snow or blend the sky the perfect shade of twilight.

“I think maybe I’ve helped them find some wonderful, fulfilling, gratifying activity that they can do for the rest of their lives,” Hankins says.

Bitten by the Bob Bug

Some of the pupils in his instructor training course are professional artists hoping to add another tool to their arsenal. But others are just lifelong Ross fans who’ve always had this nagging feeling, deep down, that maybe they could be a painter. A seed planted by Bob when they were just kids.

Dressed in a denim “Genuine Harley Davidson” shirt and blue jeans, Monica Troy can’t help but fuss over the trees and bushes on her canvas. Those are always the hardest, she says. Bob makes it look so easy. At 73, she didn’t spend her life painting, although she loved putting her hands to work as a quilter and dabbled in stained glass. Troy came all the way from Illinois to become a certified Bob Ross instructor but she isn’t planning on using it to teach classes; truthfully, she’s just doing it for herself, she says. She grew up watching Bill Alexander and later, Ross. When the opportunity arose to come to Florida for the certification course, her husband encouraged her to go. He looks at every painting she brings home.

On the other side of the room, Rose Stauner hollers for Hankins to come look at the snow she’s expertly sprinkled on her mountain. Stauner had always wanted to be a painter, but never had the courage to make a go of it, until her daughter pushed her. Now at 67, she traveled down to New Smyrna Beach from Hunstville, Alabama to see if that painter really is somewhere inside her.

She’s been wrestling with her paint knife all morning, trying to get it to cooperate. Each time she huffs in exasperation, Hankins takes the knife from her hand to demonstrate, without an air of arrogance.

“Oh no, my snow went into the water,” Stauner exclaims, realizing her white paint has taken up residence where her water should be.

“Look, mine did too,” Hankins replies, flicking a white streak into his own water.

One of the most challenging aspects of the Ross method is perfecting the art of not fussing with what’s on the canvas, he says. Nearly everyone is tempted to revisit sections of their painting with scrutiny, hoping to tidy up their trees or reblend their sky. But the beauty of Bob is in the simplicity.

Fine artists have long criticized Ross’s method, arguing that it’s overly simplistic and repetitive. Painting the same landscapes over and over is nice and all, but it isn’t art, according to the detractors.

I’ve always felt if anybody does have sort of cross feelings about Bob, a lot of it stems maybe from either jealousy or the notion that he found something that worked and he was willing to share that with everybody.

— Nicholas Hankins

In fact, Hankins kept his Ross side hustle a secret from his art professors at the University of Tennessee Knoxville because he knew what they’d say. When he did tell one professor about his gig as a Bob Ross painting instructor, she scoffed. “God he’s awful,” he remembers her saying.

“I’ve always felt if anybody does have sort of cross feelings about Bob, a lot of it stems maybe from either jealousy or the notion that he found something that worked and he was willing to share that with everybody,” Hankins says. “Maybe some of these other folks feel like they need to protect and maintain that illusion of loftiness.”

Like Ross, who often laughed his critics right off, Hankins isn’t bothered by those who say Ross’s method isn’t real art because looking around at his classroom of students, he sees a group of people who are finally ready to call themselves artists—largely thanks to Bob.

“The difference between thinking you’re an artist and not is right up here,” says JC White, tapping his temple. The 67-year-old retired Army and Air Force veteran has been painting in his free time his entire life, but it wasn’t until 2012 that he mustered up the courage to label himself an “artist.”

“Ross suggests anyone can be an artist,” White says. While that might peeve those who strive to preserve the idea that art belongs to an exalted few, it’s a soothing sentiment for those who find solace in the stroke of a paintbrush.

In this room of painters, some realized that they were artists at the age of 11, others at 67, but regardless of age, it was Ross who gently guided them to the canvas—who gave them permission to try.

Perhaps, that is the biggest responsibility Hankins feels. Not to perfect his technique or train up the next generation of Bob Ross’s, but to create a space like Ross did, a space where people believe that maybe they can be an artist.

Hankins leaves his easel at the front of the room to admire his students’ “Northern Lights” and lend a helping hand to those who need it. He pauses behind Stauner’s easel and steps two paces back. With his back against the wall, finger to his lips and head tilted, he stands in silence for a minute or two. Then, he says, “What if…”

“I always felt like I was kind of painting to impress my dad,” he says. “I guess I still do to some extent.”