by Craig Pittman | August 25, 2016

Thanks a Lot-tery

Florida’s gambling governor and a jook-joint hero

I walked into my neighborhood Publix one night in 2012 and immediately spotted a man in line for Powerball tickets who was far better dressed than the usual gamblers. The lottery line offers a cross section of the Sunshine State’s poor to middle-class residents: young and old, fat and skinny, gay and straight, white, black, Hispanic, Asian, you name it. This guy had deeply bronzed skin and white hair, and he wore a classic blue blazer, expensive slacks and tassel loafers. The other folks in line were chatting with him and snapping pictures of him with their phones.

“Hello, Governor,” I said to ex-governor Charlie Crist, aka the Tan Man. He gave me his broadest smile, one so bright it could be the bulb atop a lighthouse. When I asked what he was doing there, he reached for the oldest cliché possible: “You can’t win if you don’t play.”

Someone else asked him what the state could do with the money if Florida itself won the jackpot. He shot back: “We could pay our teachers better!”

Ah, the irony. The justification for starting the Florida lottery in 1987 was to raise money for education—but it turned into a classic shell game. Once the lottery money started pouring in, the legislature siphoned off money from the original education budget to spend it elsewhere. Schools wound up worse off than before.

The lottery money that does go to education doesn’t go to elementary, middle school or high school classrooms. Instead, it’s been spent primarily on college scholarships and school construction. Meanwhile, to assure everyone that the games are honest, lottery officials hired a former cop as an inspector general, who was once accused of (but never charged with) participating in a home invasion. Somehow he didn’t catch that 18 stores were selling tickets that produced a mathematically impossible number of winners. One player collected 568 times in 15 months.

That’s the Florida way, of course: Step right up and try your luck at a crooked game! Every Florida resident knows this is happening, yet all they do is grumble about it, usually while standing in line to buy tickets.

Living in Florida is a daily gamble anyway, what with the sharks and sinkholes and lightning strikes. Thus it shouldn’t be a surprise that Floridians are inclined to throw away—excuse me, risk—a lot of money on games of chance. In addition to the lottery, we’ve got horse racing and dog racing and jai alai. But bring up the idea of allowing casinos to set up here (a move backed by one part-time resident named Donald J. Trump), and you’ll hear a lot of people (including Jeb Bush) start howling. The voters have repeatedly shot that plan down.

Instead, we have cruise ships that take gamblers into international waters, where they can sail around and lose money playing slot machines, roulette and baccarat all night, then return to port. Florida has more of these Cruises to Nowhere than any other state—and don’t tell me that’s not symbolic.

We Floridians have always had mixed emotions about gambling, condemning it even as we embrace it. Back before Florida became a state, all gambling was illegal, yet Floridians frequently entertained themselves by betting on horse races, dog fights, cock fights, cards, dice and spinning wheels. There were times during that era, one historian noted, “when gambling seemed to overshadow all other illegal activity.”

The legal system did little to discourage it. Grand juries might indict a score of gamblers, but they were seldom punished—too many jurors were players. In those days the state was infested with crooked faro dealers, toting their rigged layouts from town to town, fleecing the unwary and hustling away. The itinerant gamblers tended to show up in a town anytime a crowd of suckers ripe for the plucking did. They always flocked to Tallahassee, for instance, when the territorial legislature was in session.

The gambling bug didn’t fly away after Florida became a state. Gambling became a way for Floridians to entertain tourists and separate them from their money. What could be more Floridian than that?

In the depths of the Depression, when Florida became desperate for revenue, the legislature voted to legalize wagering on horse and dog races so the proceeds could be taxed. Then betting on jai alai was legalized, and for a while even slot machines were allowed.

But the casinos and so forth were designed to appeal to the wealthy snowbirds. The games that filched pennies from the poor were the ones that really had an impact on the rest of the country, thanks in part to Florida’s toughest writer.

Over the years, Florida has been a refuge and a muse for plenty of writers—science fiction authors Piers Anthony, Jeff VanderMeer and Hugh Howey; and thriller writers Charles Willeford, Randy Wayne White and Paul Levine. But when I say “Florida’s toughest writer,” you probably think I mean Hemingway, who loved to take a poke at a passing poet. Or you might think I mean Carl Hiaasen, who was a hard-nosed investigative reporter before he became a columnist and author.

I’m not referring to either. I believe Zora Neale Hurston, the darling of the Harlem Renaissance, could whup them both.

Hurston grew up in Eatonville, one of the few Florida towns back then with a black mayor and marshal. During the Depression, she traveled around the state collecting folklore for FDR’s Works Progress Administration. She hit the phosphate mines, sawmills and turpentine camps—places far from civilization. She knew that was where she’d find plenty of songs and stories, as well as plenty of trouble.

“All of these places have men and women who are fugitives from justice,” she wrote, finding they were “quick to sunshine and quick to anger. A little word, look, or gesture can move them either to love or to sticking a knife between your ribs.” As a result, her life “was in danger several times.”

Sometimes she packed a pistol, but mostly she relied on her quick wit. “If I had not learned how to take care of myself in these circumstances, I could have been maimed or killed,” she wrote. She’d drive into camp and tell people that she “was also a fugitive from justice, ‘bootlegging.’ They were hot behind me in Jacksonville and they wanted me in Miami. So I was hiding out. That sounded reasonable. Bootleggers always have cars. I was taken in.”

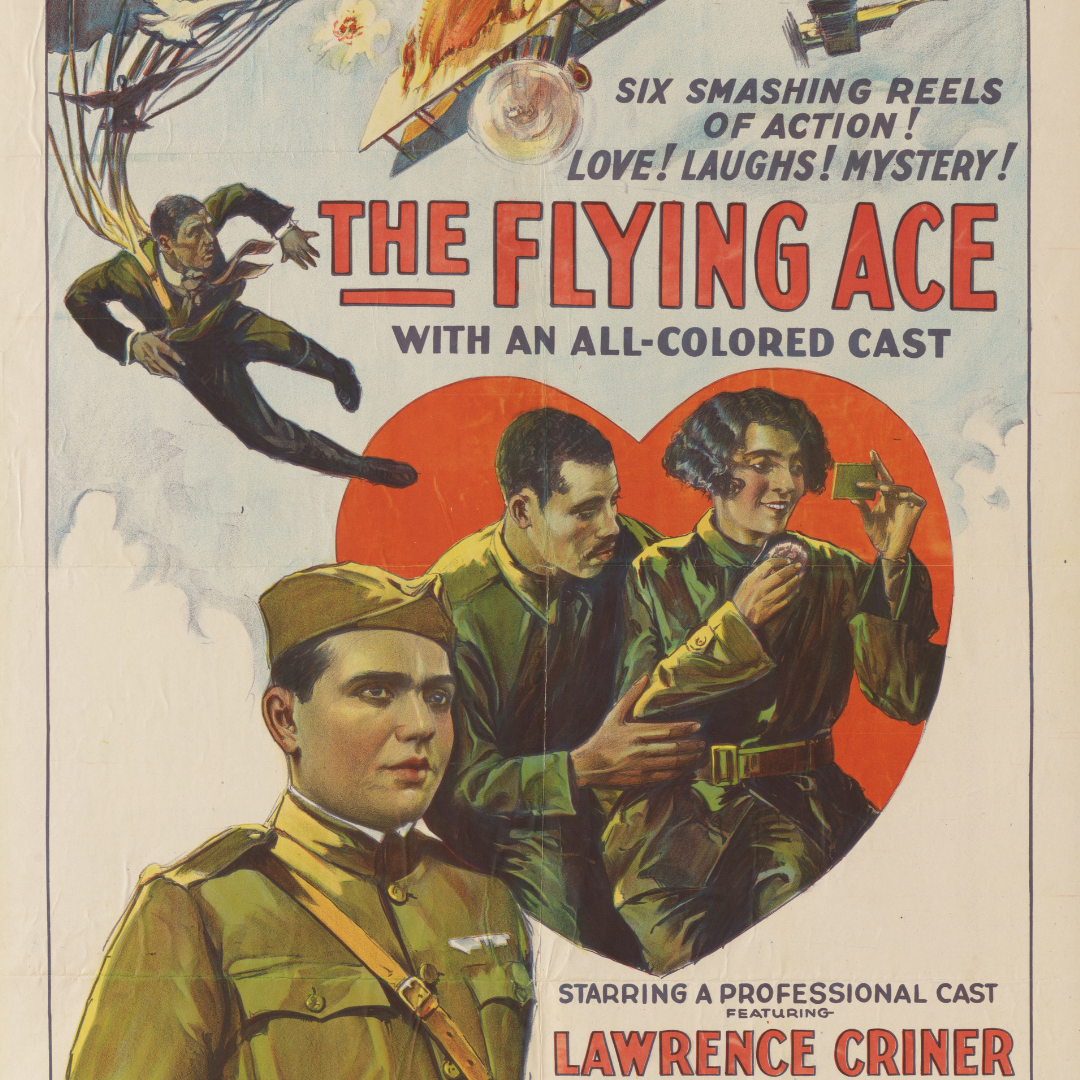

From her research she brought back fresh reports about the way people really talked, including one word nobody had ever put in print before: “jook.”

Florida has contributed some memorable phrases to the English language (“Don’t tase me, bro!” “the Cuban relatives,” “Stand Your Ground”), but “jook,” also known as “juke,” is our greatest single-word contribution. Hurston’s 1935 book Mules and Men was the first place the word was used in print, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. In her book’s glossary, she defines a jook as “a fun house. Where they sing, dance, gamble, love, and compose ‘blues’ songs incidentally.”

In another essay, she expounded: “Jook is a word for a Negro pleasure house. It may mean a bawdy house. It may mean the house set apart … where the men and women dance, drink and gamble. Often, it is a combination of all these … Musically speaking, the Jook is the most important place in America.”

Hurston loved hanging around jooks, watching the dancers grinding away (“jooking”). She would sing along with the guitarist providing the music. She picked up a lot of folk songs that way—and occasionally something more.

“It was in a sawmill jook in Polk County that I almost got cut to death,” she wrote. She was saved by a friend named Big Sweet, who was gambling at a nearby table. The ensuing brawl involved women and men armed with “switch-blades, ice picks, and old-fashioned razors.”

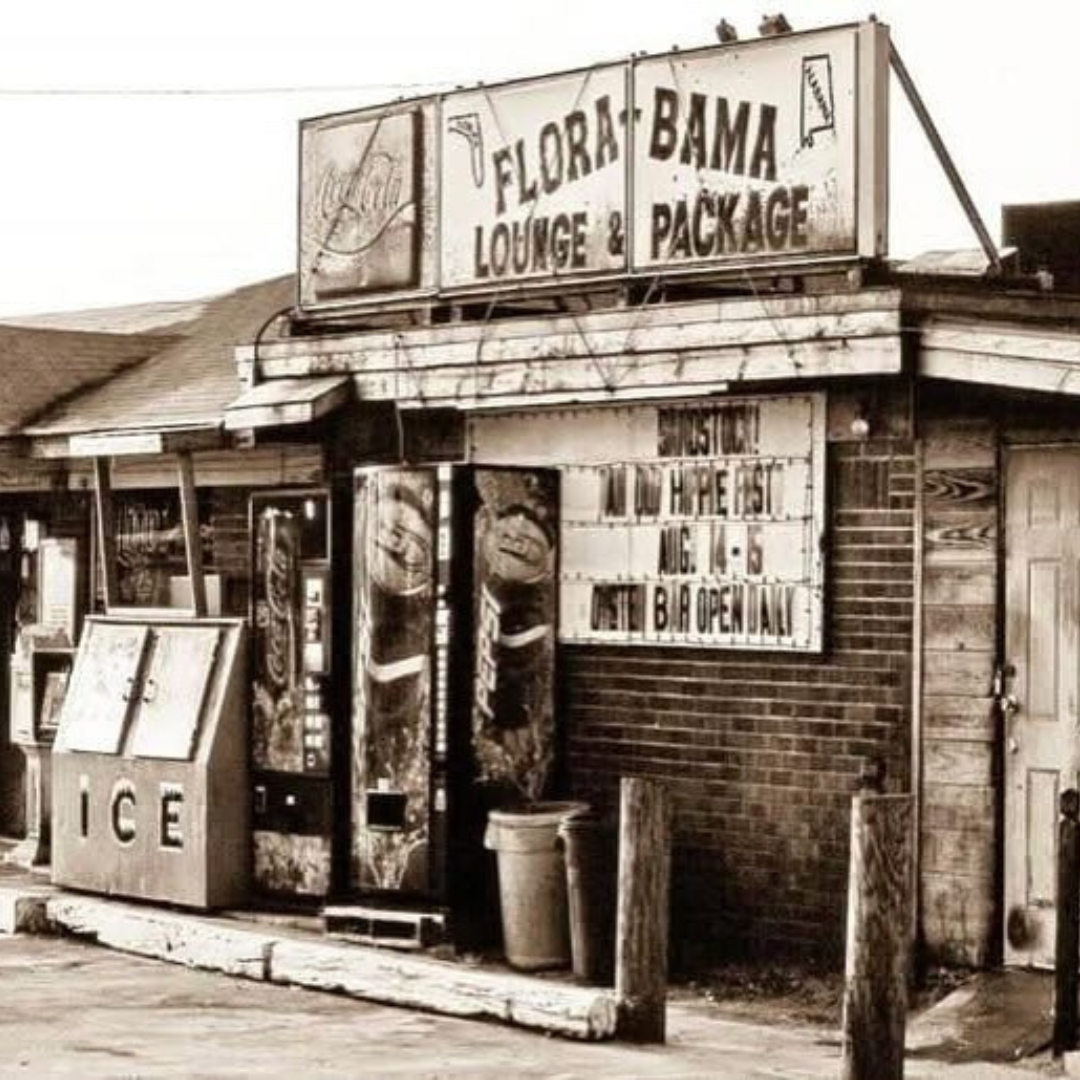

“Jook” expanded to mean any roadhouse. In 1939, the WPA Guide to Florida (to which Hurston contributed) commented on one particular stretch of pavement: “Strung along the highway west of Jacksonville are many ‘jooks’ of the type found on the outskirts of almost all large Florida cities,” in which “patrons … drink and dance to the music of a ‘jook organ,’ a nickel-in-the-slot, heavy-toned, electric phonograph.” Thus we got the jukebox.

Over time, “juke” became a sports term for dodging an opponent with fancy footwork. More recently, it came to mean dancing around the truth and faking things.

In the TV show The Wire, the cops talk about underreporting or misclassifying crimes to hide their failures, calling it “juking the stats.” But that’s another story.

Excerpted from OH, FLORIDA: How America’s Weirdest State Influences the Rest of the Country by Craig Pittman. Copyright © 2016 by the author and reprinted with permission of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.