An Interview With ‘The Perfect Neighbor’ Filmmaker Geeta Gandbhir

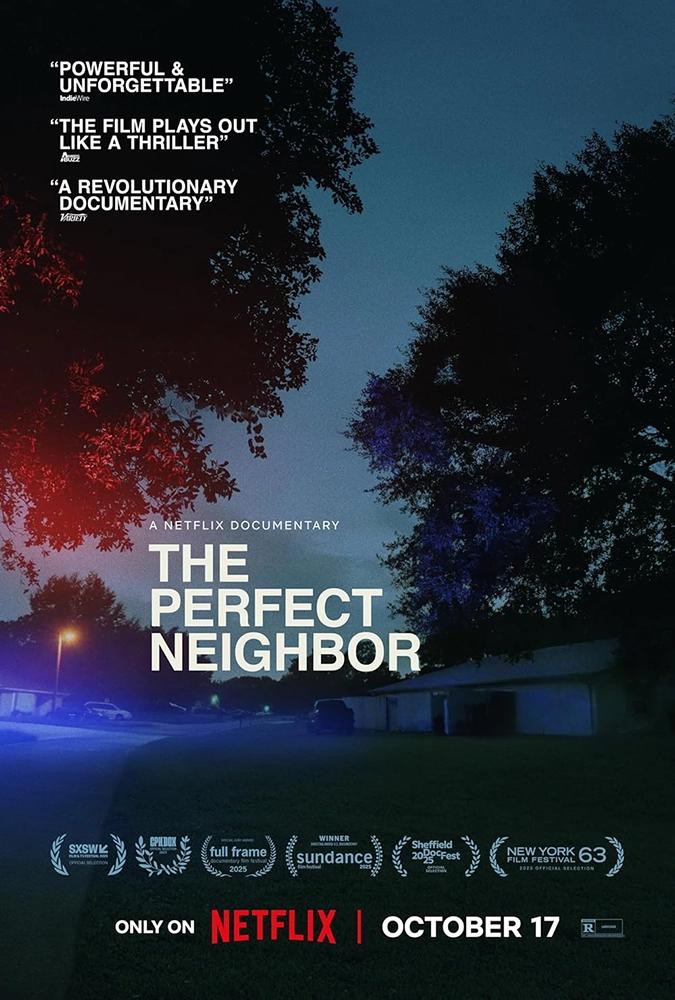

"The Perfect Neighbor" director Geeta Gandbhir discusses the tragedy behind this Oscar-nominated documentary, which almost exclusively uses body-cam footage.

Among this year’s Academy Award nominees for best documentary, the most anticipated contender is an intense and absorbing documentary about a tragic shooting in Ocala. In June 2023 Ajike Owens, a 35-year-old Black mother of four children, was killed by Susan Lorincz, her 58-year-old white neighbor, who fired a gun through her front door after two years of conflict over the play of neighborhood kids. “The Perfect Neighbor” recounts the nightmarish scenario almost entirely through police body-camera and related footage (including Ring and dash cameras), building a complex narrative out of sources common to YouTube and social media videos—where contentious run-ins with belligerent “Karens” are the clickbait norm.

The film, which won a directing award at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival, offers something much deeper and painfully relevant, at once a portrait of community solidarity, the failures of law enforcement—especially amid racial divisions—and the deadly impact of Florida’s Stand Your Ground law. Filmmaker Geeta Gandbhir didn’t know she was making a documentary when a call came from her husband’s family (producer Nikon Kwantu) with the news that Owens, who was his cousin’s best friend, had been shot. “We immediately jumped in to try to support the family,” Gandbhir says, “To get media attention around the murder, because it was not really being covered. It was only covered by very local news at best. Without media attention, law enforcement may not be as quick to act. (Lorincz) hadn’t been arrested because of Stand Your Ground laws in Florida, and that ongoing investigation. We were able to get the family on the news there (and) amp up the noise around it.” Lorincz was charged four days after the shooting, and in 2024 was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Two months after the incident, Gandbhir received 30 hours of footage through the Freedom of Information Act and began working through it. “It was detective work, also grief work,” she says. “We were trying to process how this could happen. We couldn’t believe it. How does someone pick up a gun over such a trivial dispute with their neighbor?” There was one way to find out. The filmmaker felt she could tell the story with the material she had, “and we wouldn’t have to go back and re-traumatize the family and the community.” Owens’s mother gave her blessing, and Gandbhir began.

Flamingo recently caught up with the filmmaker, whose short film “The Devil is Busy” also is Oscar-nominated, on a recent Zoom conversation. Gandbhir talks about the issues raised by “The Perfect Neighbor”—both ethical and creative—and the effect it’s had since its premiere on Netflix in October 2025, where it’s been seen by millions of subscribers.

Someone who turns on Fetflix could take this as another “true crime” drama, but it actually troubles that concept.

Geeta Gandbhir: Sure. I’ll be really honest with you. I worked in scripted (productions) for the first 12 years of my career in film. The (comparables) of what I was trying to make was something like “The Blair Witch Project.” It felt like a horror film. We also felt the body camera footage was undeniable. What you see is events unfolding organically. Surveillance can be a violent tool of the state. We wanted to subvert the use of that by using (it) to humanize this beautiful community as they were before this crime. And you never get to see that. So often, we as people of color are dehumanized and criminalized after we are victims of crime. It was really critical to me to show the children as kids. And to show this tight-knit, multiracial community, and how one outlier with her access to a gun and being emboldened by Stand Your Ground laws could change everything.

Did you have any rules for how you would use the material?

GG: Was there anything we could not use? No, because the material is public record. For children … It was critical for us to get permission from the parents. If we could not, you can see that some of the footage is blurred. Some of it was blurred by the police. We think they meant to redact everybody’s faces, and they just didn’t. We sought out the community members who were in the film and if they wanted to participate, we acquired a release from them, and if they didn’t, we blurred them. I think our personal rule was that we wanted to live in the body camera footage. We used some material we had shot, for example, the vigil and the funeral. We wanted to make something that played like a scripted film, that felt like a thriller. The film community that we have is so important, but we wanted to do something that would talk to a larger audience.

The past year has seen a lot of thoughtful, immersive docs that make use of tools like cell phones (like HBO’s “The Alabama Solution”) or explore ideas around surveillance and social media (“Predators”) in illuminating ways. How do you feel about being part of that?

GG: There’s nothing truer than the idea that art reflects life and life reflects art, that we are a mirror to each other. I applaud all the filmmakers who are using innovative techniques to tell their stories. We’re living in a time where content creation and storytelling is now in everyone’s hands. For a long time it was difficult. Documentary filmmaking was originally a colonial exercise. One that only people with a certain amount of money could undertake. And now there is more access. I think that’s really profound.

What’s the feeling in the community now that the film is out there, and their lives are, in a way, on the global stage?

GG: We showed the film to the community—before it premiered on Netflix. Obviously, it was painful to relive. I think it was cathartic for them. They said that they understood what we were doing, and they felt seen and heard, and they also didn’t want this to happen to another community like theirs. I would say this film has the best of us, and the worst. And that community was the best. That has been incredibly meaningful to us, and we are so grateful to them. Pamela Dias, Ajike’s mother, told us a story before we sent it to Sundance about how she was this bright, vibrant person, big dreams, big personality. She had this dream of being an entrepreneur. One of the last conversations (they ha), she said to her mom, “You wait, one day the whole world is going to know my name.” So for her mother, this is that fulfillment, the fulfillment of a legacy.

Have you heard from any Florida lawmakers who have seen the film?

GG: It’s kind of insane, but no, we haven’t heard directly from anyone there. Sheriff Billy Woods, who’s in the film, said that it is 100% factual because it’s body camera footage, and that’s what happened. With the laws that exist in Florida, because the footage is public record and (under) the Sunshine Law, we were not required to gain consent from any law enforcement. We’d love for this to be shown as police training. Unfortunately, what you see in this is the police, although very professional and polite, never recognize Susan as a threat, and they never recognize the community as worth protecting. They just see her as a nuisance. She was always a threat, but they didn’t see that. And so, the system failed. Susan weaponized her whiteness, her privilege and victimhood, and she tried to weaponize the police. Ultimately, the worst outcomes happen. We lost Ajike, and Susan is to spend, ostensibly, the rest of her life in prison. The system failed her, too.

For more interviews with Florida filmmakers, click here.

About the Author

Steve, a Tallahassee native and Flamingo contributor since 2017, has written about film, music, art and other popular culture for publications including The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, the Atlanta-Journal Constitution, GQ, and The Los Angeles Times. He is the artistic director for the Tallahassee Film Festival and writes a monthly film newsletter for Flamingo, Dollar Matinee.