by | December 10, 2025

Restoring the River of Grass: What 25 Years of Work Has Revealed

A milestone year for The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) brings new momentum—and new hope—to the ecosystem

Steve Davis reaches into crystalline water and pulls out a clump of periphyton, a mixture of algae, microbes, fungi, plant debris and bacteria. It looks like submerged moss, hardly the type of thing that would draw your eye unless you are someone like Davis, chief science officer of The Everglades Foundation.

“When we see this, we know the quality of the water is impeccable,” he says of the mass, an important source of food and oxygen for the life teeming within these waters.

Had Davis been standing in this same spot—a vast wet prairie deep within the Everglades—at the start of his career in 1995, he surely would not have made such a proclamation. The Glades were dying, and along with them, the ecosystems throughout Florida’s lower third, from the wetlands along the Kissimmee River to the seagrass beds of Florida Bay.

Florida’s forefathers had “drained the swamp,” as they called the Everglades, eager to plant farms and build houses, and unaware of the environmental havoc they would unleash.

On Dec. 11, 2000—25 years ago this month—President Bill Clinton authorized the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP), one of the largest and most ambitious ecosystem restorations ever undertaken. It incorporated 68 engineering projects to restore the flow of water through the parched landscape, which is home to 2,000 plant and animal species (68 of which are endangered) and the drinking water source for millions of South Floridians. The state and federal governments agreed to share the costs and the workload, and appointed the South Florida Water Management District and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to lead the endeavor. They also received support from the scientific community, including the Everglades Foundation, which was founded in 1993 to advance Everglades research, policy and public support for restoration.

Damning Consequences

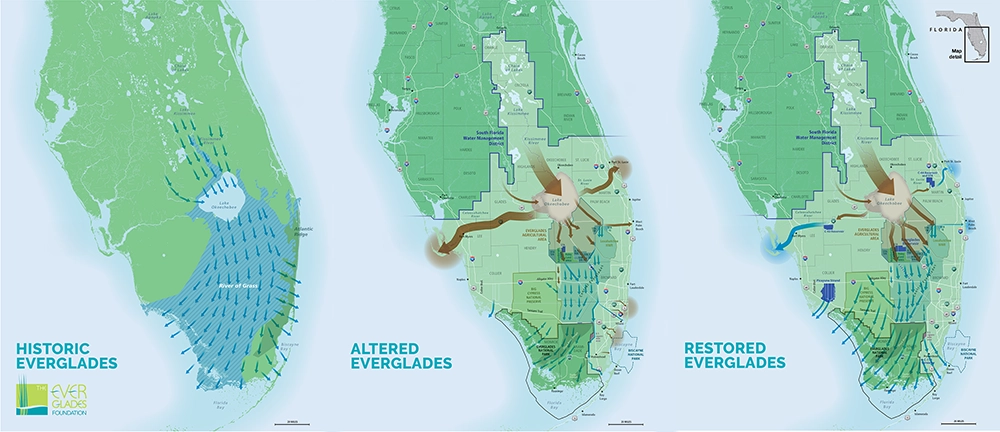

“It was this large, continuous area, over 200 miles in length,” Davis says while on an airboat tour just north of the Tamiami Trail in Miami-Dade County. Historically, the Everglades watershed originated north of Lake Okeechobee and fanned out, like a massive sprinkler, hydrating millions of acres south of the lake. The freshwater fed vast sloughs, inundated swamps and maintained the balance of fresh and saltwater along coastal estuaries. Its movement was gradual and consistent, supporting both wetland habitats and elevated ones, like the tree islands emerging from this sawgrass sea.

Developers began draining in the late 1880s. The most egregious change, from an ecological perspective, was the replumbing of the 730-square-mile Lake Okeechobee, severing it from the Everglades and flushing its water east and west through the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee Rivers. In 1948, Congress authorized the Central and Southern Florida project, creating a network of more than 1,000 miles of canals, levees and water control structures throughout southern Florida. The freshwater Everglades shrank by half. Roads restricted water’s movement, too. The Tamiami Trail, completed in 1928, was the “first dam across the river of grass,” Davis explains. It both starved Everglades National Park of water and impounded water north of the road, flooding areas such as the tree islands, the ancestral homes of the Seminole and Miccosukee. Making matters worse, water that did reach the Everglades was laden with phosphorus and nitrogen from agricultural fertilizers. Water quality got so bad that the federal government sued the state in 1998. CERP seeks to address poor water quality through massive filter marshes that purify water on its southward journey.

The hydrology of South Florida will never be what it was—6.3 million people live along the Glades’ eastern border alone—but CERP is designed to replicate nature’s design as best as possible in today’s realities.

Ten Years Down the River

It took years for CERP to gain traction. Planning was intense, federal funding was initially sporadic and the complexity of each component was mindboggling. Imagine returning the 103-mile Kissimmee River, which was cut in half and straightened into a canal, back into a serpentine, wetlands-lined waterbody. Or installing an 11-mile seepage barrier, 50 feet underground, to keep the water destined for the Everglades from flooding adjacent communities. Or raising 3.5 miles of Tamiami Trail so that water can flow beneath it.

In the last decade, buoyed by bipartisanship and billions in state and federal dollars, projects are coming online, breaking ground and entering the pipeline for future appropriations. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers anticipates finalizing CERP by 2035. This month, the Biscayne Bay Coastal Wetlands Project, a project under CERP that is rehabilitating 190 acres of freshwater wetlands and improving seagrass beds and oyster reefs, marks its completion. Next month, a ribbon cutting for the Picayune Strand Restoration Project—the very first CERP construction started—is scheduled. That project involved filling in massive drainage canals, leveling old roads and building pump stations to more evenly spread water across the landscape.

But the project Davis and Everglades Foundation CEO Eric Eikenberg are most excited for is the construction of a new reservoir, the size of Manhattan, south of Lake Okeechobee. A new deal struck this summer allows the state to take the lead on several key components of CERP, including the reservoir, which will be expedited by five years.

“I refer to it as the heart bypass surgery for the Everglades,” Davis says, “because the lake was historically the heart, we disconnected it from the body, and this reservoir is the means by which we can redirect the water south.” Once complete, the reservoir will store some 78 billion gallons of water at any given time and direct 470 billion gallons per year to the Everglades and Florida Bay. Most of that water right now is flushed down the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie Rivers; massive reservoirs have been built in both watersheds to manage stormwater runoff and to ensure the estuaries receive adequate freshwater during the dry season.

At a time of massive cutbacks and chasm-like divides over environmental and climate science, CERP appears to be something of a political darling. The state and federal government continue to pour funding into it; Florida allocated $1.4 billion for Everglades restoration and water quality initiatives this year alone.

“You talk about other environmental issues, and the minute you mention it, you lose half the audience,” Eikenberg says. “(CERP) is bipartisan. The most liberal to the most conservative dedicate themselves to getting this done.”