by | November 25, 2025

Inside Bill Haast’s Miami Serpentarium

The self-trained herpetologist studied venom and survived bites at his South Florida labs.

Amidst bellows of alligators and the excited chatter of tourists, occasionally, Naia Hannah Haast and her younger sister, Shantih, would hear the approaching sound of a helicopter landing out on their front yard. It meant one thing: someone had been bitten by a venomous snake, and their father’s blood might be the only cure. This was the reality of living at the Miami Serpentarium, a roadside attraction and laboratory where the Haast family collected vials of venom for researchers across the country.

“A couple of times the Air Force would send the helicopter to just land in our front yard and take him away,” Shantih recalls.

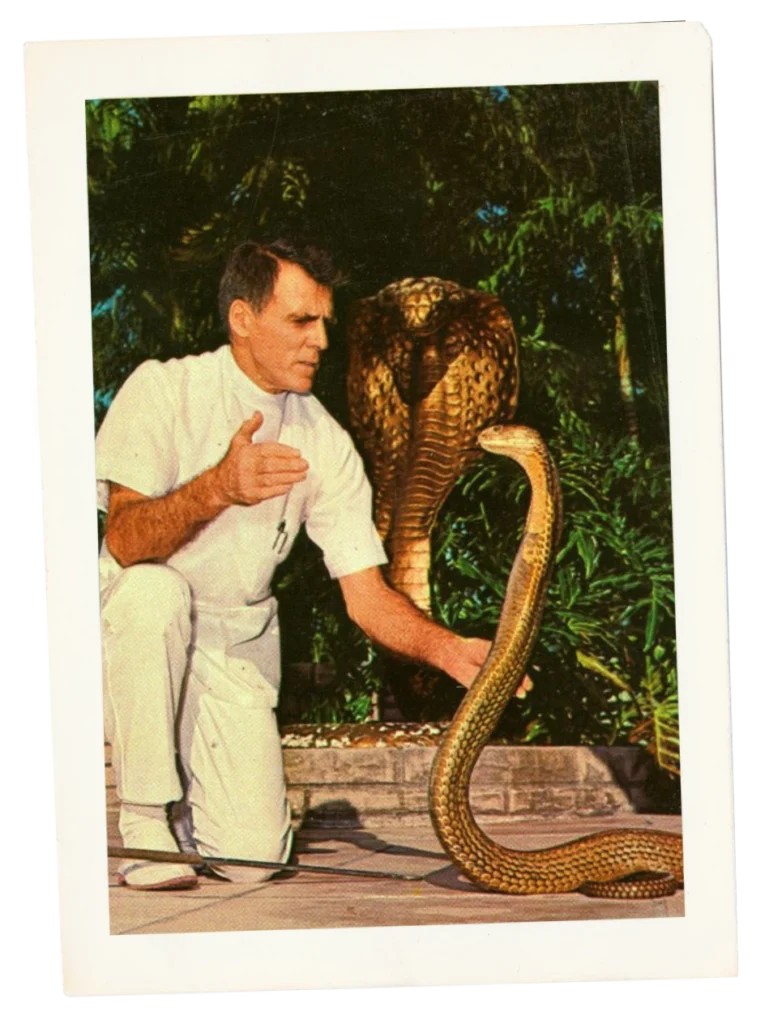

Under the shadow of a giant Cobra statue off the shoulder of U.S. Route 1, their mother, Clarita Haast, gave tours, while in the labs, their father, Bill Haast, cared for and extracted venom from thousands of snakes—among them, the king cobra.

Over the course of his 100-year life, Bill was bitten at least 172 times by venomous snakes—including his own king cobras, whose paralyzing venom is one of the deadliest in the world. The self-trained herpetologist is perhaps best known for his ability to survive the bites, not because of some innate resistance, but because of an experiment he designed, in which he was the only subject: Bill injected himself with cocktails of various snake toxins that he collected from his serpents, gradually working up to lethal doses in an attempt to gain immunity.

To the media, he was a sensation. To thousands of tourists, he was a dedicated—and at times, enigmatic—snake man of South Florida. To renowned herpetologists across the globe, Bill remains a revered pioneer in his field.

Snake Farm

Today, the final stretch of U.S. 1—the highway that stretches from Fort Kent, Maine to Key West along America’s east coast—is surrounded by an endless sea of strip malls. But when Bill Haast opened the Miami Serpentarium on a 3 ¼-acre plot in December of 1947, he was surrounded by dense palms and pines.

A makeshift wire fence, three deep concrete pits filled with reptiles and a hand-painted sign that read “SNAKES” marked the unceremonious beginnings of the Miami Serpentarium. By April of 1948, the Haasts had made a thousand dollars (worth about $13,000 today) from the trickle of passersby lured in by the makeshift sign.

Bill’s goal was never to run a roadside attraction—it was always about learning from the snakes. Since becoming enamored with the reptiles at age 11, his passion never waned, even after he was first bitten by a venomous snake, a small timber rattlesnake, just a year later. So, as an adult, he spent his time in the Serpentarium’s labs collecting venom, both by himself and in front of audiences of fascinated tourists.

He was more of a snake-person than a people-person, but he was happy to talk with any visitor who shared an interest. Always calm, sincere and a bit hard to figure out: talking to Bill “was like talking to Yoda,” Shantih says.

But Clarita, who married Bill just five months before opening the Serpentarium, had enough charm to make the attraction’s first-ever visitors enamored with three concrete pits of slithering reptiles. She had never seen a snake until meeting Bill, but from the breadth of knowledge she displayed during her educational talks, visitors never could have guessed it.

“The attraction wouldn’t be there at all if it wasn’t for our mom,” Naia Hannah says. “She said that the Serpentarium has a purpose, and she was going to beautify it, make it so people could come and enjoy being there and be educated at the same time. She goes, ‘Might as well watch you work and learn something.’ So she truly created the Serpentarium. That was awesome because it supported the research. Until later, it all turned around just the opposite—, the research really took over.”

Every dollar went back into the Serpentarium. And by the time Clarita and Bill welcomed their first daughter, Naia Hannah, whose name was derived from the scientific name for king cobra, 50,000 people were visiting annually.

What once was a spartan snake farm became a bonafide research institution surrounded by a thoughtfully landscaped animal park. Palm trees collected from every corner of the world provided shade to the animals, while curious tourists peered through large glass windows, hoping for a chance to see Bill extract venom in his chromatography labs, which he would eventually send to research facilities across the country.

And tucked behind it all was the Haast residence, built on the same property as the Serpentarium. For Naia Hannah and Shantih, it meant a childhood filled with rambunctious reptiles and never a dull moment.

While other kids helped their parents mow the lawn, the Haast girls were busy dodging rattlesnakes that had escaped into their own backyard during a hurricane. When others begged their parents for a small dog, Naia begged hers for a lion (and got one). “Then the lion would get out and run across the highway. I’m like, ‘Oh my god, I gotta get this cat,’” she recalls. They played amidst the indigo snakes on good days and ran from crocodiles on the more eventful ones.

His first king cobra bite was very vivid to me. I was nine, and the world stopped for a minute.

—Naia Hannah Haast

One night, as she was walking their dog around the premises, Naia bumped into another Serpentarium resident. An African crocodile had padded its way through the Serpentarium, pushed open an unlocked set of doors and exited through the gift shop. He was headed for the Haast home, and the sisters turned on their car to try to distract him with its headlights. The croc bit back: “He grabbed the car and just shook the heck out of it,” Shantih says. The reptile ripped the bumper clean off before Bill showed up to shoo him back to his pit—first, trying to tow the 1,000 pound reptile with a Volkswagen van. “He just put his feet down and he wouldn’t move,” Shantih says. “He outweighed the car.” It wasn’t until the local fire department showed up that the Haasts successfully carried the croc back to its pen.

“Almost every day was something like that,” Shantih says.

Venom in His Veins

Life at the Serpentarium could certainly be dangerous, especially for Bill, who woke up before the sun to handle some of the deadliest reptiles in the world. In his 1965 book, “Cobras in his Garden,” a midlife look at Bill’s career, author Harry Kursh puts it best: potentially lethal bites were an “occupational hazard” for Bill. But OSHA wasn’t around when the Serpentarium was in its heyday, nor would it have pursued the same solution as Bill.

Starting in 1948, Bill began his self-immunization experiment. On an evening in September—without telling a soul, not even his wife—he grabbed a hypodermic needle and injected a few drops of cobra venom into his arm. Over the course of the next 11 years, Bill injected himself over 80 times, gradually working up to what should have been lethal doses.

Many believe it worked: he was bitten by venomous cobras dozens of times throughout his career, and over 170 times by venomous snakes in his 100-year life. “His first king cobra bite was very vivid to me,” Naia says. “I was nine, and the world stopped for a minute.”

That first bite sent Bill to the hospital where his pulse eventually became undetectable and he started losing sensation across his body. The following afternoon, he was already back to work at the Serpentarium with the cobras.

“The amazing part was our mom; she told the doctors how to handle it,” Naia Hannah says. “She held it all together. He wouldn’t (have lived) if it wasn’t for her.”

“She’d give him antivenom before they even got (to the hospital),” Shantih adds.

The worst was in 1956 when a Siamese cobra quickly sunk its fangs into his skin on national television. Bill ended up in an iron lung—he had stopped breathing altogether. But still, after intense medical attention, he survived.

Bill’s life wasn’t the only one his blood may have saved. He was flown to hospitals across Florida to donate blood for victims of venomous snake bites. In one case in 1965—the ninth time his blood had been requested—he was rushed to Jacksonville, where his blood was given to a coral bite patient.

“Before the transfusion,” Bill said at the time, “(The patient’s) eyes were closed and only his fingers moved slightly, perhaps involuntarily. After the transfusion, when the doctor asked him a question, he opened his eyes slightly, and soon afterward drew his knees up to his chest and tried to scratch his throat with his hand. All good signs. Everyone was sure the worst was over and plans were made for our return to Miami.”

The Legacy Lives On

Bill ran the Serpentarium until 1984, several years after a crocodilian killed a child who had fallen into its pit. Around the same time, Bill and Clarita split. After 37 years, four shows a day, hundreds of thousands of visitors and countless vials of venom, the Serpentarium closed. The 35-foot stucco cobra that stood at the attraction’s entrance, serving as a beacon for reptile-curious roadtrippers, broke into pieces as it fell from the grasp of removal cranes.

But Bill didn’t give up on his passion—he continued to extract venom in nearby Punta Gorda—and neither did the next generation of herpetologists, who found new purpose in his labs.

For someone who always cared about reptiles and loved reptiles, Mr. Haast was a bigger-than-life figure.

—Joe Wasilewski

Joe Wasilewski was just 20 years old when he started cleaning cages at the Miami Serpentarium. Now he’s enjoyed a storied career in herpetology, including an appointment to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the title of “the snake man of the Everglades” and a director role at the King Cobra Conservancy, where he works alongside Naia Hannah and Shantih Haast.

And he’s not alone. “We call ourselves Serpentarium alumni, and a few people that have gone through there have really made big inroads in conservation and venom research,” Wasilewski says.

It’s an impressive alumni list for a small institution, including herpetologists like Jack Facente, one of the only coral snake venom producers in the world, Ron Magill, the communications director for Zoo Miami and Romulus Whitaker, a renowned reptile conservationist based in India.

For all of them, the Serpentarium was its own sort of school where Bill’s quiet dedication and unwavering passion paved the way for reptile enthusiasts to become reptile experts. “For someone who always cared about reptiles and loved reptiles, Mr. Haast was a bigger-than-life figure,” Wasilewski says.

It took a lot for Bill to fully trust people, Wasilewski says, but when working around some of the world’s most lethal animals, precautionary distrust is a preferable quality. But once you joined the Serpentarium family, you didn’t leave. “I was bitten by a forest Cobra in ‘78,” Wasilewski says. “That was two years after (I worked at) the Serpentarium. Mr. and Mrs. Haast came to the hospital with the antivenom. They saved my life. Not only am I indebted because of my work, but he saved my life, too.”

Today, a shopping center stands in the Serpentarium’s place, obscuring almost any memory of the labs and attraction, save for a nearby historical marker that shares a brief history. But for the many reptile researchers who studied under Bill and the school of the Serpentarium, the memory will never fade. “I’m afraid,” Wasilewski says, “as time goes on without a museum or something, it might be lost. It’ll never be completely lost with reptile people, but it’ll get hidden.”

For more fascinating Floridians, click here.

About the Author

Helen has an aptitude for finding alligators and a passion for covering the weird and wonderful of Florida. The Tallahassee native graduated with her bachelor's degree from the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University. At Flamingo, she helps organize advertising and write stories (usually about Florida's fantastic fauna).