by | October 20, 2025

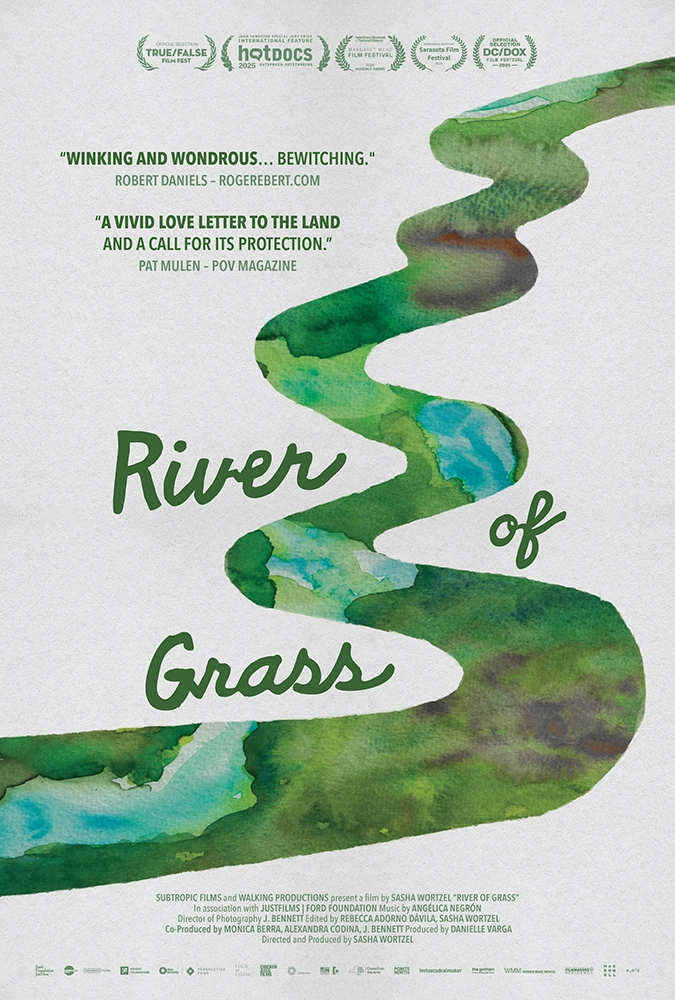

‘River of Grass’ is Retold in a New Documentary

Filmmaker Sasha Wortzel draws on the work of both Marjory Stoneman Douglas, known for her iconic book about the Everglades, and conservation activist Betty Osceola in her debut, "River of Grass."

Inspired by Marjory Stoneman Douglas and her 1947 book of the same name, “River of Grass” is a fittingly poetic, yet also exhaustively researched, cinematic exploration of the Everglades. The 1.5 million acres of Southwest Florida wetlands are protected as a U.S. national park yet forever threatened by an array of factors, from developers to climate change, and most recently American immigration policy. The documentary is an emotional project for filmmaker Sasha Wortzel, who ultimately added her own voice as its narrator.

“I was very resistant to putting myself so personally in it,” says the Fort Myers native. “But every time I talked about the film, wrote about it (and) pitched about it, it was coming from this really personal place of love for home and processing my own grief about the loss of home and the environment.” The film, which launched its theatrical run on Oct. 17 at the Coral Gables Art Cinema, earned Wortzel the Florida Filmmaker Award (co-sponsored by Flamingo) at the recent Tallahassee Film Festival, which includes a $1,000 cash prize and a porcelain flamingo trophy (in striking pink).

We caught up with Wortzel for a chat about her connection with Douglas and her classic book, as well as the film’s other key figure, Betty Osceola—an activist, educator and airboat captain who belongs to the Miccosukee Tribe—and about how she came to her “prismatic” approach to this vast subject.

What got you started making “River of Grass”?

Sasha Wortzel: I had been living in New York, and every time I’d come home, I was witnessing more and more destruction, more devastation and worsening water quality. I felt like I needed to make a film, and I needed to move home to do it. I need to take this very immersive, place-based approach … spending time with the people in the film, even when I wasn’t filming, and building community and being involved on the ground. I got a studio residency at this place called Oolite Arts on Miami Beach in 2019. But I started the project in the development/research phase in 2017. I did a month in the Everglades National Park as an artist-in-residence with the program called AIRIE (Artists in Residence in Everglades). I was there just after Hurricane Irma in November 2017. Parts of the park were still destroyed or underwater. Phones were down. I had this very analog experience of getting to know the place and finding people and scientists and park rangers and the folks that would ultimately be in the film. That was kind of the first month. And then I went back to New York, where I was working, (I) applied for funding, got our first development funding from Sundance, and then said, “It’s now or never. I’m going home and I’m making this movie.”

Just to backtrack for a second, what first got you into filmmaking?

SW: I went to an arts magnet high school and I was in the theater program. Right next to the black box theater, there was a media program. I got into writing and directing theater and performance. But I was like, what if I could take these ideas and translate them to film? I was also doing photography, and my parents are real cinephiles, so I just grew up watching a ton of cinema—particularly from the ’30s and ’40s. It was really not until later, after I went to New College … that I started making my own kind of artist videos. When I went to grad school at Hunter College, I studied film and got an MFA in this Integrated Media Arts program and really deepened my engagement with cinema.

How did this project kick into gear? Did you ever feel like you might get lost in the research?

SW: It is really easy to get lost in it. I think naively I started out with the idea that I would make a film that dealt with the history of this water system and how it had been transformed from this very free-flowing expanse to this very stifled flow of canals and dry acreage for development. (I learned) the ecology, the hydrology, the legal aspects, indigenous history. But I’m drawn to projects that are complex and that are a lot more about systems, and I love the research phase. It was really fun to dive into all kinds of Florida literature, from Zora Neale Hurston to Marjory Stoneman Douglas.

Whose work is the core of the film, of course.

SW: I was really inspired by the way that Douglas builds the story of the Everglades, from the rock to the plants to the water, the animals and the people. Weaving these different threads and also using the pronoun “they” for the Everglades, establishing that the Everglades are not just one singular thing. They are a network of distinct ecosystems that are all threaded together by water. That inspired me to approach the project in this very prismatic way, in which we would look at different communities across the region (that) maybe were navigating slightly different circumstances. However, we’re all connected, right? What happens upstream, where folks are fighting to stop sugar cane burning, is inextricably linked to where I grew up on the southwest coast of Florida, where we’re experiencing red tide blooms. The project really did kick into gear during that month in the residency. That’s when I really met many of the people who would become participants in the project, particularly Betty Osceola. She took me on her airboat. We talked for a long time, and she invited me to join her on this prayer walk, where we would walk 120 miles around Lake Okeechobee. I showed up, and that started that part of the project.

Tell us about your fascination with Marjory Stoneman Douglas.

SW: I knew that Douglas’s book was still the essential resource guide to the Everglades. Even though it was written in 1947, it was extremely relevant. It felt like I was reading a survival guide. She’s warning us in 1947 that if we don’t repair the system and change our relationship to our environment, we’re going to lose it. And here we are decades later, and that is still true, even more urgently. I really wanted to take her text and translate it to cinema, to bring it into the future, to offer it to a wider audience who may not know her name, may not go pick up her book. And then, putting the text and her words in conversation with people like Betty, who are on the ground today, continuing her work. Not just her work, but the coalition that was around her. It was later that I had this dream. Marjory did actually come to me (in a dream) and say, “You know, it’s great that you’re making this film and using my book. But what about me? People have forgotten who I am. I have more things to say.” I feel like we really only knew Marjory as the author of “River of Grass,” the activist later in life. But who else was she? That’s when I came across this clip from an incredible interview with her when she’s in her 90s at her iconic house in Coconut Grove. Eventually, we were able to uncover the raw dailies (from the interview) that became woven into the film. I really wanted to put these two powerhouses, Marjory Stoneman Douglas and Betty Osceola, in conversation. These different bodies of knowledge—there is tension there—but there’s a world in which we need both of these bodies of language to exist together. Sometimes Marjory’s book gets very celebrated. Maybe less so are we acknowledging all the knowledge and wisdom that comes from a different (indigenous) way of knowing.

The movie opens in theaters at a shockingly timely moment when the Everglades have been part of an intense legal battle over the so-called “Alligator Alcatraz” detention center.

SW: We never could have predicted that. The film can offer a primer that prepares us all for this moment, that gives us some of the history of how we got here, how we got to building an awful detention center in the middle of our drinking water and on indigenous lands. It’s a continuation of what’s been ongoing, but more intensified. The film highlights this eerily parallel moment in 1969 when the state of Florida decided that it would try to build the world’s largest jet port, four times the size of JFK, in the Everglades, because tourism was booming and the population was growing. Folks like Marjory Stoneman Douglas, activist and tribal leader Buffalo Tiger and the Miccosukee tribe, hunters, fishermen all got together and they fought it, and they shut that project down. I hope that can be a roadmap for what we’re doing now, which is hopefully shutting down the detention center. Friends of the Everglades, Marjory’s legacy organization, is front and center in the fight, along with Betty Osceola and others and a wide coalition.

For more interviews with Florida filmmakers, click here.

About the Author

Steve, a Tallahassee native and Flamingo contributor since 2017, has written about film, music, art and other popular culture for publications including The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, the Atlanta-Journal Constitution, GQ, and The Los Angeles Times. He is the artistic director for the Tallahassee Film Festival and writes a monthly film newsletter for Flamingo, Dollar Matinee.