by | October 1, 2025

Grady Hendrix’s Latest Book Casts a Spell on Florida

In "Witchcraft for Wayward Girls," Southern horror author Grady Hendrix goes to St. Augustine.

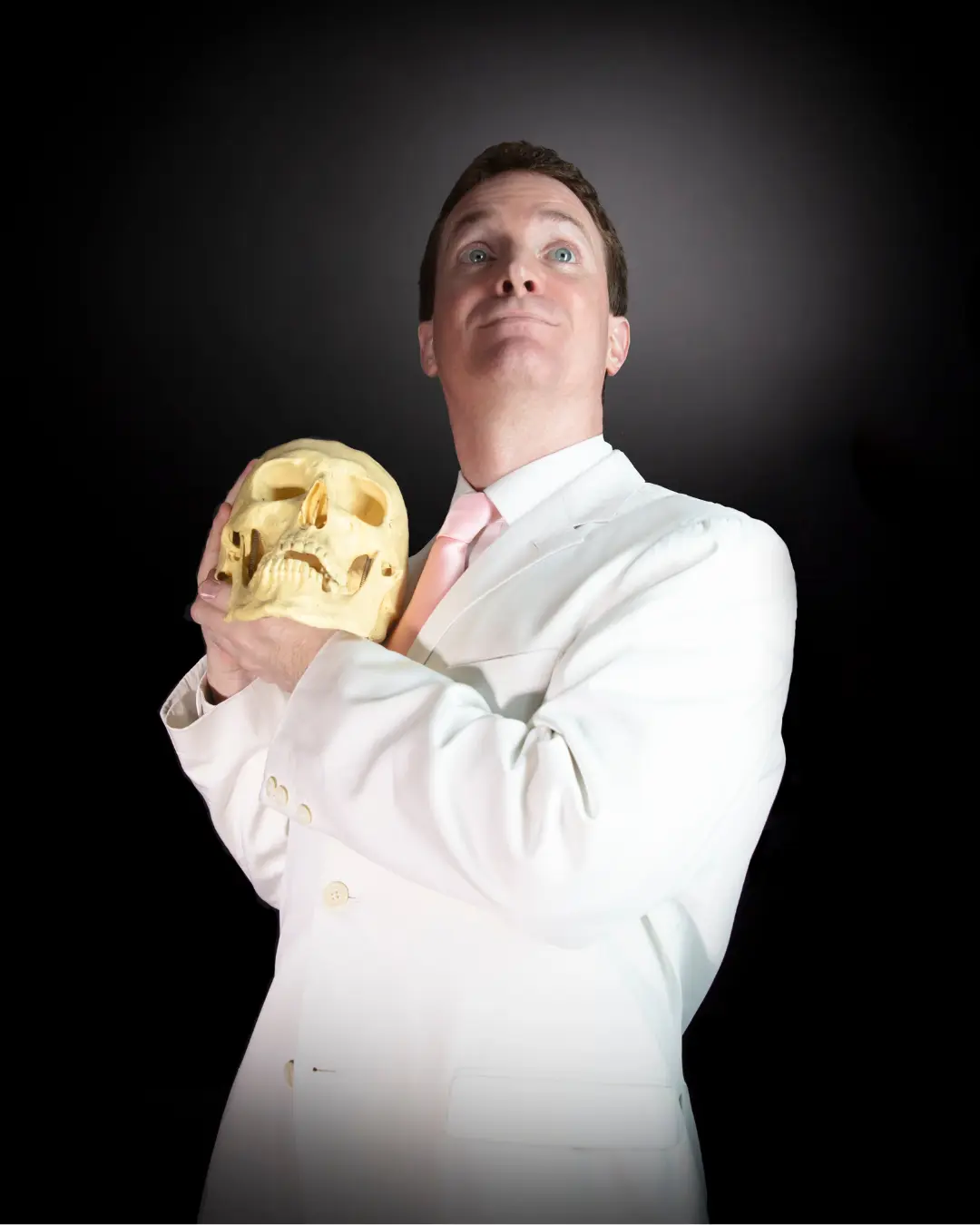

This time of year, Florida is still swelteringly hot. But when acclaimed horror writer Grady Hendrix came to town, he sent a shiver down the spine of Sunshine State. In his latest book, “Witchcraft for Wayward Girls,” the Charleston-native travels to St. Augustine, where he explores what happens when the occult consumes the teenage residents of a 1970s maternity home. Flamingo sat down with Hendrix to learn about his inspiration, the real people behind his characters and if he’d ever dare to return to Florida.

How much of this was inspired by real places in St. Augustine?

Grady Hendrix: Okay, the house I have in mind is not in St Augustine. It was actually a house that was a maternity home in Alabama, and long since defunct. And then I had also spoken to a friend of mine who owns a bookstore in Savannah. She grew up in Saint Augustine in the early 70s, and so I did some interviews with her. There was actually a maternity home in St. Pete that people who were there have written about quite a bit, and I was always really fascinated by it, because it was basically the end of the train line, and that’s why it was located there. It’s like, you take the train to the last stop, and there you go. But it’s all patch-worked together.

This story was, in part, inspired by your relatives who lived in maternity homes. What were their experiences like?

GH: One of my relatives who was sent to a maternity home was sent to Florida, but she’s passed away now, and no one remembers where. One was in her, I think, 70s at the time (when) her son had reached out to her and she wanted to reunite. And that was the moment she told the family she’d been sent away when she was a teenager, and then another relative a few years later, also revealed—she was about in her 50s or 60s at the time—that she had been sent away, and her daughter never reunited with her. I couldn’t wrap my head around (the idea of) “Wait—you could have a kid, and your kid could be dead or alive or sick or happy or unhappy or in jail and you would just have no clue.” And I wound up reading this book by Ann Fessler called “The Girls Who Went Away,” which is an oral history of homes. There’s not much written about the homes. There’s “The Girls Who Went Away” and “Wake Up Little Susie,” which is a much more academic book about the Black experience of maternity homes. But those are sort of it, in terms of accessible histories that are comprehensive.

I really love Florida, because it’s sort of the end of the road. You can’t move anywhere if you’re running away from something. That’s as far as it goes.

—Grady Hendrix

These girls were sent and they lived in these homes. They were away from home. They were sequestered from the town they were in, or had real strict limitations on how to interact with people. They were in a group of girls that they didn’t even know their real names, and they were all pregnant, and most of them had no idea what was going to happen at nine months. It was wild what we did to these kids. These are like 14 and 15 and 16 year old kids who are being asked to make these decisions. It’s just inhuman that we did that to them. And I was just like, there’s a story there. And then it took many more years for me to feel like I was ready to tackle it. And even then, this book took me two years to write. Normally, it takes me about one. It just kicked my ass, left right center.

This book is set in the 70s, but was there a reason you wanted to tell this story now?

GH: I didn’t say, “Oh, I’m going to write this book because it’s relevant” or anything. Honestly, it was just the next book I was ready to write. I also feel like this stuff is not ever untimely. One of my relatives is a family law practitioner who specializes in adoption, and she’s like, there is never a time in my life where I am not dealing with a client who is a teenager who is being hidden. You know, they’re in an aunt’s house, they’re upstairs. They’re pretending to have mono, whatever it is. Florence Crittenton, besides the Salvation Army and the Catholic Charities, was one of the big nationwide groups of maternity homes. Roe v. Wade in ‘73 made a lot of the homes repurpose themselves somewhat and sort of refocus their mission. But I drove by a sign this February that was advertising Florence Crittenton homes looking for foster homes for pregnant teenagers. So, it’s always timely.

How does the setting of Florida shape the plot of “Witchcraft for Wayward Girls?”

GH: I really love Florida, because it’s sort of the end of the road. You can’t move anywhere if you’re running away from something. That’s as far as it goes. And so I’ve always found Florida kind of wild.

One thing that really got me and really changed the book was reading the local paper, the St. Augustine Record. There were all these stories about protests, and these hippies on the beach and kids, long hair and druggies and all this stuff. It’s the same conflict you’d find probably anywhere in the (United States), between young people looking for a place to drink some beer and get high and make out, and cops and old people who disapprove of that. But it really made me realize that as much as we can joke about the 70s—oh, bell bottoms and sideburns and all the clothes were ugly—people were really at war. You know, there was this real idea there was a war going on and that it was going to rip this country in two. You’re looking at young people who were literally being murdered in the streets. And the old generation is celebrating. They’re quite literally sending our friends and us off to Vietnam, and we are coming back in wheelchairs and body bags. And then you had old people looking at young people like they’re dirty, they’re on drugs, they use profanity, they’ve got long hair, they are blowing up ROTC offices. I think, if I did anywhere in America and zoomed in that deep, I would have seen that. But St. Augustine really was a good cross section of that.

And then the other thing is, there is a real person in the book from St. Augustine, Virgil Stewart. When I was reading the paper, I realized it was a civil rights flashpoint in the early 60s. I mean, Martin Luther King came down and said, “This is where the war is happening.” And Virgil Stewart was the police chief. He basically, by all accounts, was working with the Klan who terrorized the Black citizens of St. Augustine for about two years. And the cop who’s in this, who we never named, who’s sort of the head of the police, that’s Virgil Stewart, in my mind. And that, to me, was always, even though it’s not front and center, in the book. It’s always a part of it.

Will you return to Florida in any future books?

GH: I don’t have any plans to. But if I was writing about Florida again, I’d do Central Florida. I think Central Florida is weird, and there’s also a real history in the 19th century and the early 20th century of sort of utopian communities being founded in Florida, and land scams. There were a ton in Northern and Central Florida, and I’ve always found that really, really fascinating.

A long time ago, one of my first jobs was working for these guys who ran the colonial theater in South Beach in the early 90s, and it was just when South Beach was turning from old folks motels to this party town, and that was wild to be in in those early days. That was really fun. And St. Pete too. I mean, the death metal capital of America. So there’s a lot of places to come back to.

Favorite Florida books?

GH: Charles Williford wrote four Hoke Moseley books that are all set in Miami. Every few years I will read them again. He’s got this very flat affect, whether he’s discovering a corpse or talking about his poplin jumpsuit. It’s all the same tone. I find them so great, because every now and then there’ll just be these spikes of emotion that really catch you off guard.

Janisse Ray’s “Ecology of a Cracker Childhood.” I read that right before writing this to get some mood, and it really hit me hard.

Tananarive Due writes a lot about Florida, and her book, “The Reformatory,” is set there. I love her short stories. I’m always in awe of people’s short stories because I’m not good at writing them. So her collections, like “Ghost Summer” and “The Wishing Pool,” have a ton of stories set in Florida that just really blew me away.

Larry Baker’s “The Flamingo Rising.” It’s a sort of coming of age novel written by a kid whose dad owned the drive-in. It just captured this kind of mood of roadside attractions in America, and the dad is crazy. It’s like reading “The Great Santini” by Pat Conroy. You don’t remember anything about the book, but you remember the dad.

John D. MacDonald writes a lot of mysteries set in Florida, but he wrote a standalone book called “The Condominium” in the 70s. It’s this huge book, and the thriller part of it is not that exciting, but it’s this deep dive on 70s development politics and how shoddy the construction of all the condos that were thrown up around Miami were. I loved it. It’s tedious as hell, but I really liked it.

For monthly updates on all things Florida authors and reads, subscribe to Well-Read here.

About the Author

Helen has an aptitude for finding alligators and a passion for covering the weird and wonderful of Florida. The Tallahassee native graduated with her bachelor's degree from the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University. At Flamingo, she helps organize advertising and write stories (usually about Florida's fantastic fauna).