by | August 11, 2025

Stetson Kennedy’s Fight for Civil Rights

How this Florida folklorist took down the KKK and became the most hated man in American along the way.

On election day in 1950, Stetson Kennedy—journalist, folklorist, civil rights activist and champion of the poor—turned up in the tiny hamlet of Switzerland, Fla. Before he was able to vote, Kennedy was confronted by a small mob threatening him with broken beer bottles. A couple of deputies ran them off, only to arrest Kennedy for supposedly violating the law by possessing campaign materials near a polling station.

Kennedy was running as a write-in Independent candidate for the U.S. Senate. His opponents were the well-known Democrat George Smathers and Republican John Booth. In those days, Republicans in Florida were as scarce as hen’s teeth. Kennedy was well known, too, mostly as a troublemaker. Folk songwriter Woody Guthrie, Kennedy’s friend, fellow leftist and frequent houseguest, composed a campaign song for him. His campaign slogan was “Not White Supremacy, but Right Supremacy!” This did not endear him to most white folks. A back injury had kept Kennedy out of World War II; he said if he couldn’t fight fascists abroad, he’d fight them at home. “It was the least I could do,” he said when I interviewed him in 2003. The St. Johns County cops may have saved him that day at the polling station, but they didn’t like him, either. Kennedy laughed: “I thought they were going to lynch me.”

Several years before the election, in the mid-1940s, Kennedy infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan. Posing as a member, he exposed Klan secrets by sharing the information with the FBI, a popular syndicated columnist and even the writers of the “Superman” radio program so that it could be used as plot material for the Man of Steel’s battle against right-wing extremists. After a few years as a “klavalier” in the Nathan Bedford Forrest Klavern #1, a frustrated Kennedy traveled to Washington, D.C., to demand action from the House Un-American Activities Committee. Dragging a trunkful of KKK material, he entered the Capitol wearing full Klan regalia and asked to speak to the committee before the police kicked him out. Kennedy finally dropped his cover to testify at the trial of two Georgia neo-Nazis the following year.

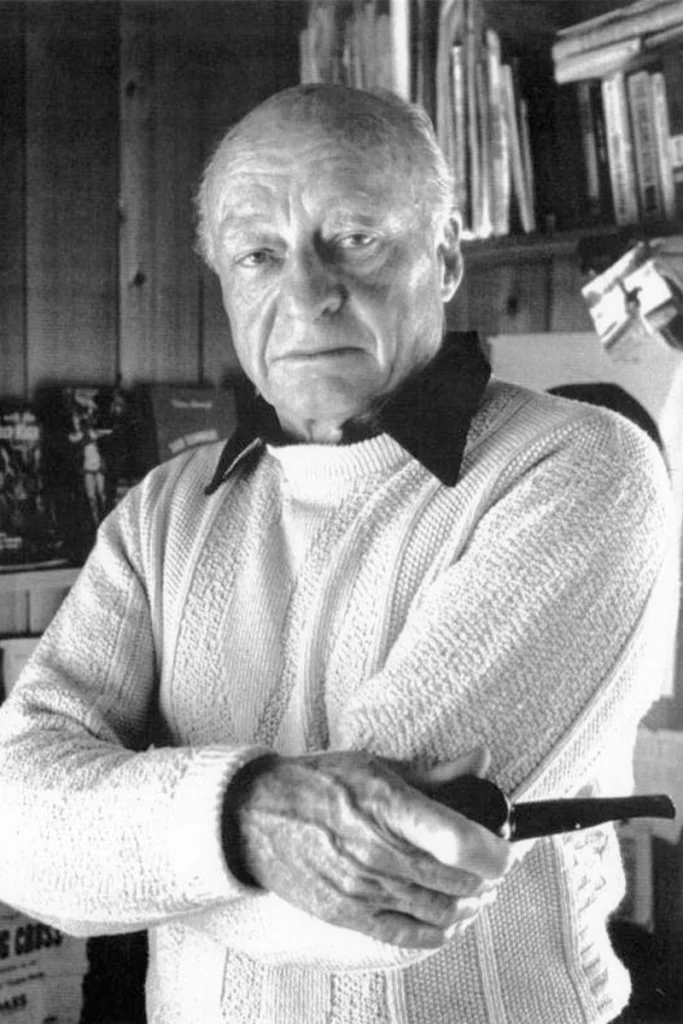

Stetson told me these stories when he was a spunky 87, with eyes still a bright robin-egg blue. We sat drinking coffee on the deck of his lakeside home south of Jacksonville, watching little blue herons wading in the shallows. The land he bought in 1948 is now a park, while his cabin is a museum and a National Literary Landmark. Kennedy wrote eight books here; Guthrie wrote scores of songs here, too. Kennedy named his little piece of Florida “Beluthahatchee,” a term from Black Seminole lore, which means “all is forgiven and all is forgotten.”

Stetson delighted in recounting stories of when people wanted to kill him—or at least run him out of the country. People that Guthrie called “racey-haters, pinky-baiters, dead-brainers and fraidy cats.” Kennedy’s 1946 book, “Southern Exposure,” was a scathing account of racism, neo-slavery and rapacious capitalism in America that made him notorious. His union work, articles for The Nation and other progressive publications, as well as his attacks on white supremacy, made him a constant target for violence. As he wrote in a 1995 letter, “The Klan said the Bible said that Jim Crow was God’s will and therefore eternal, and anyone, white or (Black), who dared say nay thereby made themselves a likely candidate for social, economic and even rope lynching.” Enraged, the Klan threatened to burn down ’s house, leaving an ominous note: “S.K.—You are finished; we have just begun!—KKK.”

Writing With Zora Neale Hurston

William Stetson Kennedy was an unlikely provocateur. Born in 1916, Kennedy was the child of a well-off Jacksonville family that traced its lineage back to signers of the Declaration of Independence. His grandfather was an officer in the Confederate army. He could have chosen the life of a Southern gent, pursuing a career in the law or business or Dixiecrat politics. But Stetson Kennedy never did anything the easy way. He was radicalized as a child when Klansmen assaulted his family’s much-loved Black housekeeper, supposedly for arguing with a white bus driver. At Robert E. Lee High School (now called Riverside), Kennedy recalled seeing white boys knocking Black delivery boys off their bikes for fun.

In 1935, he enrolled at the University of Florida with a focus on creative writing. He cut class to go out in the field, documenting the Old Florida ways of railroad gandy dancers, sponge divers and Seminole shamans. College life was, he said, “politically illiterate.” With the Spanish Civil War going on at the time, he collected blankets and boots to send to the anti-fascist Spanish Republican troops. Kennedy liked to say, impishly, “I guess I invented independent studies.”

He dropped out and joined the Roosevelt administration’s Federal Writers’ Project. The program employed journalists, scholars and authors to produce local histories, guidebooks and photographic records of rural America, and record interviews with former slaves. Despite his lack of academic qualifications, Kennedy talked his way into a job as a folklorist. He was good at it—almost as good as his supervisee, Zora Neale Hurston. The author of “Mules and Men” and “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” Hurston was a Columbia University-trained anthropologist who had previously worked with Margaret Mead and Franz Boas. When she arrived at the headquarters, Carita Doggett Corse—the Florida director for the Writers’ Project—called the all-white editorial staff into her office: and she announced Hurston would be joining the program, explaining they’d have to “make allowances” for her. Hurston, “feted by New York literary circles, (was) given to putting on certain airs, including the smoking of cigarettes in the presence of white people.”

While Kennedy heaped scorn on such condescending racism, he did not dare travel the state with Hurston: A white man in a car with a Black woman was likely to ignite deadly attacks. Instead, Hurston would first drive ahead to the destination by herself, while Kennedy would follow. The stories they gathered shaped “Palmetto Country,” Kennedy’s 1942 history of Florida’s folk: mill hands, blues singers, farm laborers, fishermen and voodoo practitioners. A New York Times reviewer called the book “a forceful argument animated by an alert and justice-loving mind.” Publications closer to home, such as the prestigious Florida Historical Quarterly, ignored the book.

Few appreciated Kennedy’s work: As historian Gary Mormino said, he was “one of the most hated men in America.” After stirring the hornet’s nest with his Senate run, he decided to make himself scarce. He decamped to Paris, becoming friends with fellow exile Richard Wright and the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. American publishers wouldn’t touch his books. “I Rode With the Ku Klux Klan” (1954) came out in London, while “Jim Crow Guide to the U.S.A.” was published originally as an essay in Sartre’s literary journal in 1955 in France.

Back to Beluthahatchee

As we sat at Kennedy’s home, a couple of ospreys swooped over the lake, and the tangerine-colored sun began to sink low in the west. Kennedy and I had moved on to egg salad while I started on a glass of wine. He told me he had loved Europe, but by 1960, he’d gotten homesick: “I looked over several continents and 30 countries, searching for something more Floridian than Florida. I found plenty of bathing beauties and palm trees, but the weeds weren’t right.”

“So you came home to Florida?” I asked.

“And stayed put,” he said.

Kennedy remained at Beluthahatchee for the rest of his days, advocating for workers’ rights and championing environmental causes. He produced essays for Southern Changes and wrote more “folksay” books like the 2008 title “Grits & Grunts: Folkloric Key West.” As an increasingly frail 92-year-old, he insisted on going to Barack Obama’s 2008 inauguration, saying: “I’ve been campaigning for President Obama since 1932.”

A couple of snowy egrets landed on the deck rail. He often fed them, though when his kitchen clock struck the hour—or, more accurately, chirped the hour—they flew off. It was one of those Audubon clocks with twelve different birdsongs. He wasn’t sure he liked it. “That Yankee bird clock confuses them,” he said. Not only were the weeds outside Florida wrong, but the birds were, too.

For more fascinating Floridians, click here.

About the Author

Diane is an eighth-generation Floridian, educated at Florida State University and Oxford University. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian and the Tampa Bay Times. She has also authored four books, including “Dream State,” a historical memoir of Florida.