by | July 16, 2025

The Turtle Chasers: Volunteers Saving Freshwater Turtles and the Florida Springs

Through volunteer-led freshwater turtle surveys, the Florida Springs Institute is learning more about the health of a unique ecosystem.

It’s a cool, foggy December morning at Silver Springs State Park, just outside of Ocala. Stacie Snipes slips into a wetsuit and a snorkel mask, prepared to take a plunge into the 70-degree turquoise waters. Swimming isn’t usually allowed at the park’s main springs, but today, Snipes has a special task: to find as many freshwater turtles as she can.

Snipes is part of a crew of dozens of volunteers who love turtles so much that they spend their weekends camping overnight in state parks to help catch, collect and record data on the shelled reptiles for scientific research. The part-time diver grooms dogs for a living, but it’s turtles she cares about the most. “Turtle people tend to find other turtle people,” Snipes says.

Over the course of two survey days, volunteer scientists collected over 300 turtles for the second annual freshwater turtle survey in Silver Springs led by the Florida Springs Institute (FSI), a conservation nonprofit headquartered in High Springs. By collecting information about the turtles’ health and population sizes, scientists can learn more about the health of the overall ecosystem. It’s also part of a long-term monitoring effort, a way to track changes in species and environmental conditions over time. In doing so, the science can better inform conservation and management decisions in the future.

Swiping Softshells

Survey days are a group effort. Starting at 8 a.m., volunteers pile onto small jon boats in their wetsuits and snorkel masks. The first step, though, is to check for alligators—lots of them. When the coast is clear, they slip into the warm water and float down the river in a line, scanning for turtles among shades of green and blue.

There are a few different techniques for catching them. You can “just nab ‘em,” Snipes says, by grabbing them by their sides. You can sandwich them, using your palms on the underbelly and top of the shell. And if they’re small enough, you can close your whole hand around the shell.

“Got a turtle!” someone will suddenly say, their voice muffled through a snorkel tube.

“Softshell, softshell, softshell!” someone else will yell, in a reference to Florida softshell turtles, a tube-nosed species known for its speedy swimming. The team quickly assembles in a circle around it, ready for action. Usually, softshells sit at the bottom of the riverbed in the grass, “looking all quiet,” says Bill Hawthorne, a turtle ecologist who led the surveys at the Florida Springs Institute. Then, as soon as one person starts to approach, it will shoot off. The circle breaks as chaos ensues: Flippers and arms frantically slice through the water, trying to catch their target.

“It’s a specialized skill to be able to swim down a river and capture multiple turtles under your arms,” says Haley Moody, director of FSI. “It’s very impressive.”

Each turtle is carefully and gently transported back to the boat, where other team members place them into large collection bins. Once there are no more turtles in sight, they head back to the dock.

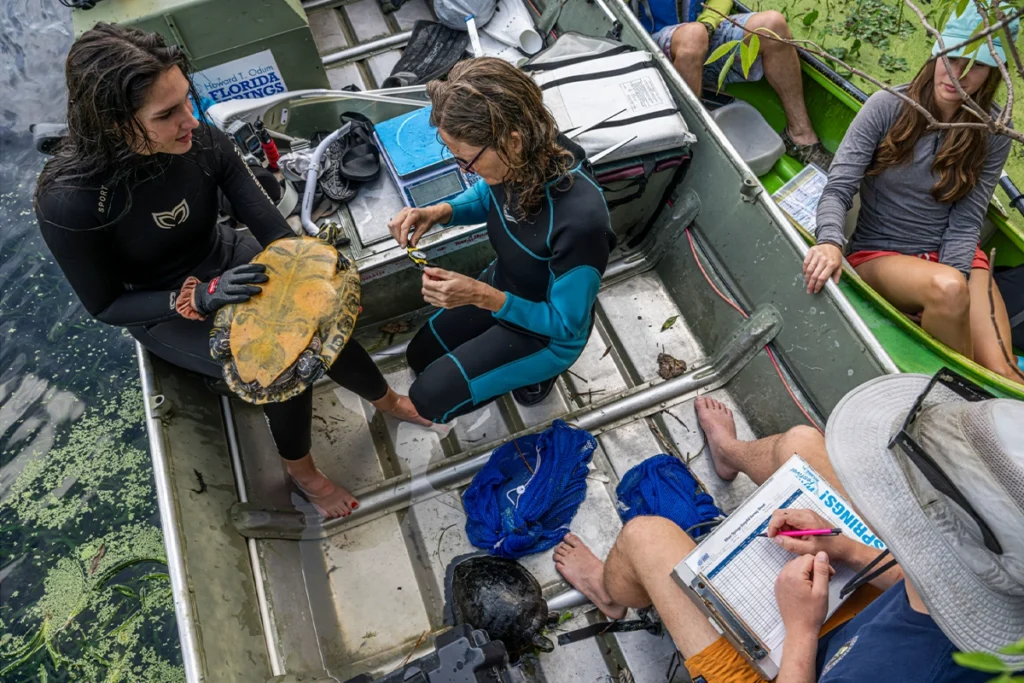

There, the processing team sips hot chocolate while they measure, photograph and assess each turtle. Some of the shelled creatures receive tattoos—small markers to identify them—and others receive tiny PIT tags, which are wildlife identification chips. X-rays and ultrasounds check for swallowed fish hooks and eggs, and blood samples check for parasites and pollutants, such as mercury.

Sick turtles undergo special health assessments. Bacterial swabs, respiratory tests, cultures and occasional necropsies are all part of the job for volunteer wildlife rehabilitator and research collaborator Kim Titterington. When she isn’t teaching dance or performing in parades at Universal Studios, she’s taking care of sick reptiles and amphibians.

Turtles, as messengers, are an effective way to communicate conservation issues. We just need to listen to the turtles.

—Jerry Johnston

One yellow-bellied slider, for example, had an oral abscess in its ear that may have been caused by organic chlorines—compounds found in pesticides and plastics—that Titterington was able to surgically treat onsite. She then kept the turtle for antibiotic treatment before releasing it back to the springs.

By understanding their threats, scientists can inform wildlife managers—and the public—on how to protect them.

“Some of it’s very sad and traumatizing and depressing, but at the same time, I feel like we’re also receiving answers to try to prevent these things in the future and help educate people,” Titterington says.

It’s a fun yet disciplined effort. Hawthorne thinks back to sitting with his interns in the boat: One person has the turtle in its lap, another is holding a pair of calipers, one has the scale and someone else is taking notes. “It’s really wholesome,” he says—even as they clean turtle poop out of the collection bins.

The survey data has helped create a baseline for Silver Springs, which is necessary for observing change over time, Hawthorne says. Ideally, these reports, which are submitted to the state wildlife agency, will help inform myriad research projects and become part of an ongoing monitoring effort. The data is available not only for scientists but also for nonprofits, students and the general public.

Eco-Sentinels

Freshwater turtles are considered indicator species: animals that give clues about the wider ecosystem by responding to changes in the environment, Hawthorne explains. And each species can yield specific information based on its environmental niche. For example, Suwannee cooter turtles are herbivores, so when populations decline, it signals fewer aquatic plants. Loggerhead musk turtles, meanwhile, snack on small snails that are sensitive to dissolved oxygen; seeing fewer loggerheads can mean fewer snails, and therefore low dissolved oxygen—a clue for poor water quality.

They’re “like a team of ecosystem sentinels,” says Jerry Johnston, a turtle ecologist at Santa Fe College who has led his own turtle surveys on the Santa Fe River since 2004.

Northern Florida, with its unique network of crystal-clear springs, is a global hotspot for freshwater turtles. “The springs are supporting the turtle diversity, and then the turtles give us information about the health of these ecosystems,” Johnston explains.

But for the past several decades, North Florida’s springshed has experienced multiple pressures—mainly, excessive groundwater pumping and agricultural runoff from fertilizers.

The combination of low water levels and nutrient pollution creates a low-oxygen and low-flow environment, which kills native vegetation and creates a phenomenon known as “dark water,” explains FSI founder Bob Knight. That’s when dark tannins from rotting leaves turn the water into a tea color that starves plants of the sunlight and oxygen they need for photosynthesis. And that means less food for wildlife like turtles, which depend on native grasses for food, Knight says.

Snipes, now in her 30s, has been swimming in Florida’s springs since she was six months old. Over the years, she’s noticed a lot of these changes firsthand, such as more algae, frequent dark water “brown-outs,” invasive plants and fewer fish.

“(Turtles) are surviving despite all the pressures we put on them,” Snipes said. “I feel like it is my responsibility to do as much as I can to help them.”

The springs might look pristine—clear water, green grasses and lots of critters milling about in the water—but “there are these little things that if we wait until it’s something visible to the naked eye, it’s too late to fix it,” says Avery Rust, a former FSI intern. That’s why long-term monitoring is so important.

“You see a lot of organizations right now that are losing funding, and they just have to stop their operations,” Rust said. “Without volunteers, it doesn’t happen.”

Community-Led Science

FSI may be new to turtle surveys, but they have a much longer history.

In 1990, Eckerd College turtle ecologist Peter Meylan started the first freshwater turtle survey at Rainbow Springs. Over the decades, he inspired multiple generations of ecologists to duplicate the model elsewhere, as Johnston and Hawthorne have.

Volunteer-led studies like this are invaluable, Johnston adds. Not only do volunteer-led studies make science accessible to a wider audience, Johnston adds, but the educational component also helps engage participants in conservation, opening the door to natural curiosity.

“We’re all doing science, therefore you’re a scientist,” Johnston says, whether you’re a student, citizen, retiree or just someone who cares a lot about wildlife. “Breaking down that perceived barrier of science as being something that ‘other people’ do, that’s a really big part of it.”

These days, Johnston’s favorite part of the surveys isn’t the thrill of catching one, or the hot cocoa, or finding a rare discovery. It’s watching the excitement on volunteers’ faces when they catch their first turtle. It’s a bonding experience, he says, experiencing the turtles’ world together for a few hours.

“Turtles, as messengers, are an effective way to communicate conservation issues,” Johnston says. “We just need to listen to the turtles.”