by Steve Dollar | August 2, 2024

JJ Grey’s Triumphant Return: ‘Olustee’ Revives Southern Soul and Swampy Blues

Southern rocker, and Jacksonville native, JJ Grey opens up after the release of his first album in 9 years to talk writing, life on the road and his love of a Rooster named Jim-Jim.

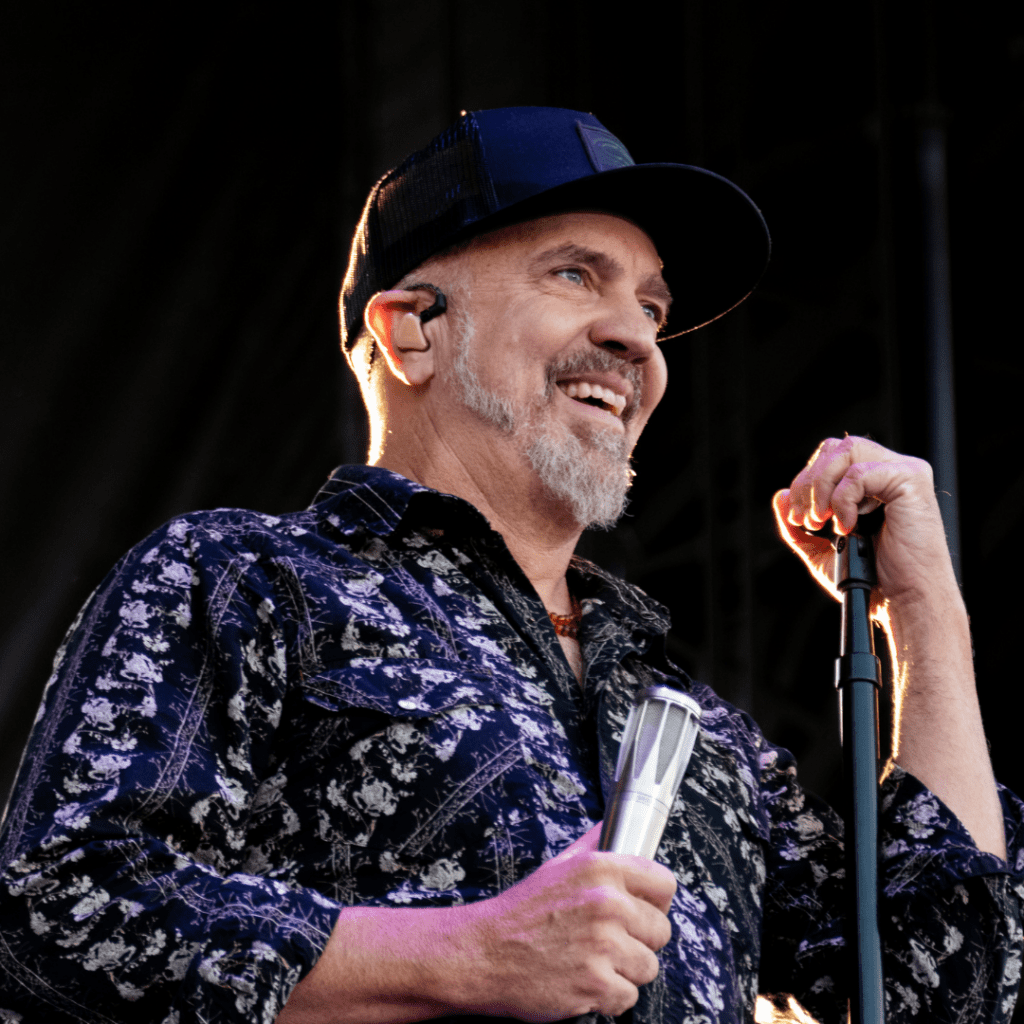

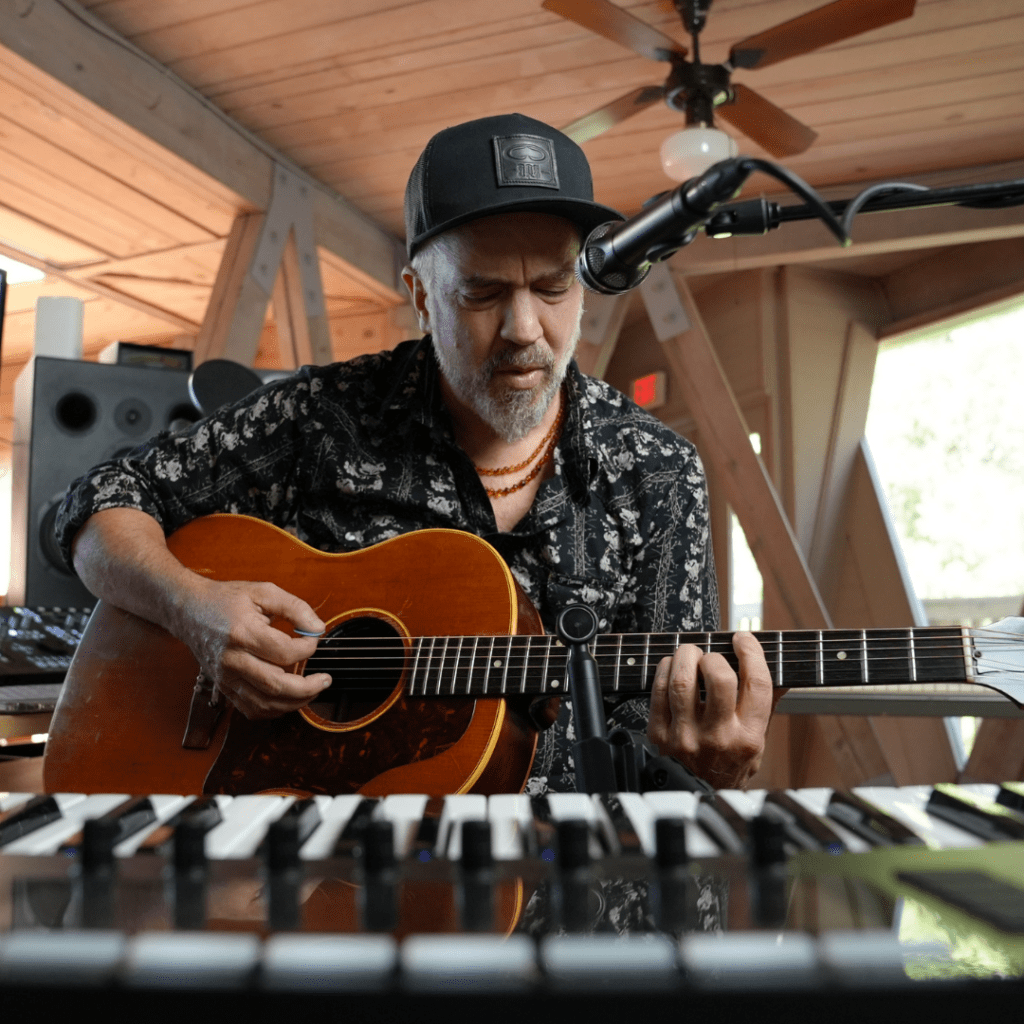

While his natural habitat of the Florida swampland inspired a career’s worth of blues- and R&B-inflected songs, JJ Grey’s second home is the stage, where audiences across the country can see the Jacksonville singer-songwriter and guitarist and his band JJ Grey & Mofro on tour throughout the summer and into October (so far). Grey’s ninth studio album “Olustee” (Alligator Records) is his first since “Ol’ Glory” was released in 2015, a stretch that was marked by the COVID-19 pandemic and its attendant disruptions.

Want to watch the interview instead? Click here.

Its 11 songs, including a cover of country music legend (and Apopka native) John Anderson’s classic “Seminole Wind,” spin like a compass of musical possibilities. Opening track “The Sea” is a fully orchestrated immersion into the cosmic questions, evoking majesty and mystery through the eyes of a stargazing beachcomber: “Laying on the sand, feeling every grain/A billion points of light, along the Milky Way.” Existential wonder gives way to immediate life-or-death concerns in the title track, an urgent rocker that references the Baker County town famous for an epic 1864 Civil War battle. The song, though, is about a series of devastating wildfires in 1998 that became collectively known as the Florida Firestorm. Elsewhere, there’s the horn-driven strut of “Top of the World” and “Free High,” the kind of surefire showstoppers that are a Mofro specialty.

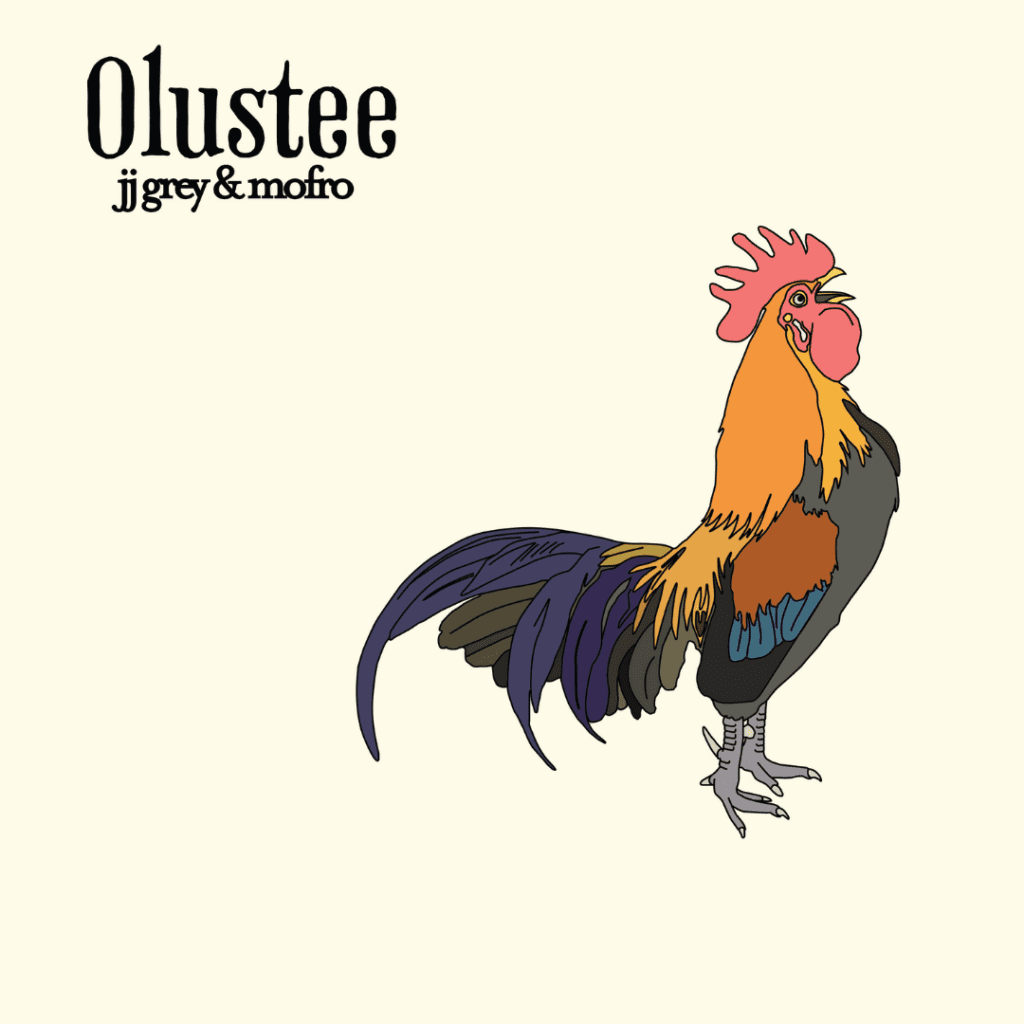

On his day off between tour stops, Grey—born John Higginbotham—hopped on Zoom for an hour to chat with Flamingo from his home in Jacksonville, where he enthusiastically discussed the joys of being back on the road, his love of Lynyrd Skynyrd and his fascination with chickens—evidenced by the rooster illustration, drawn by Grey himself, that adorns the cover of “Olustee.”

We’ve been waiting a long time since your last record. What’s been going on?

JJ Grey: I had the music done a long time ago. But I didn’t have the lyrics—exactly what I wanted to say and how I was going to say it. I heard Gamble Rogers say once that life is what happens to you while you’re making other plans. I felt like this album happened while I was making other plans. But if you added up all the time that it actually took, working on the record probably took less time than some of the other albums. It was just all spread out. It’s also COVID. That was part of the reason why the album became “self-produced.” I throw up quotations (marks) only because the album kind of produced itself. I was just along for the ride.

The songs shift easily between rowdier numbers and some very reflective ballads, and as always with your music there’s a vivid sense of what it feels like to actually be in North Florida, experiencing all the elements. How do you find that balance?

JG: On the new record, there’s a song about the rub between the idea of you and the real you and the difference and that chasm, how big it can be and how small it can be. And all the way over to (the title track, about) running from a forest fire—for your life. I don’t sit down and actually say I need this or I need that. Well, I might if I sat down and I looked down and I’ve got 12 dance numbers. It’s actually usually the other way around. I’ll have a bunch of self-reflective songs, and man, I need to have some joy, some uplifting moments, too. Even though in their own way, those self-reflective cuts are kind of in a blues tradition even if they’re not a blues song at all but in that blues tradition. A song that almost sounds sad can be uplifting, you know? I want songs to be beautiful. Some of the other songs I’ve had were like that, but I want to bring in women background singers, and I want to get a saxophone player in the horn section and get a percussionist to play on this record. Hell, I’ve been doing that since “Country Ghetto.” Every album has all those things on it. I just got a short memory, but my main thing was, I wanted things to be beautiful.

You guys are all over the country this summer. After all these years, have you found a sane way to tackle it?

JG: This is going to almost sound oxymoronic, but my life at home is a lot more chaotic. The road is much more structured. So you would think that in order to make the road (feel) sane, you would need to introduce a little chaos. But it’s the opposite. The oxymoronic side of it is, I get even more of a routine that’s more “Groundhog Day”-ish that actually sort of grounds me. I’m not “Rain Man” bad. Like “Wapner at 5. Wapner at 5.” But I’ve pretty much got a time schedule. I want to be able to workout. I want to do some sort of exercise and get outside in some way. Find good food to eat that’s a little bit lighter than the fare at home. I’ll drop 25 pounds (once) we started rehearsing. I go into a completely different mode—I only eat once a day. I don’t do that on purpose. It’s just always worked out that way.

Are there rules you go by after the show? I imagine in the old days everyone would get drunk and rowdy and pile on the bus at 3 a.m. and wake up with a hangover and start all over again.

JG: We got two buses. One of them I call the Dirtbag Bus, and then one the Goody Two-Shoes Bus. But it’s not that goody two-shoes. Invariably, I’ll end up on the Dirtbag Bus, which is actually probably the cleaner, nicer bus. Talking over loud music, if people are partying and hanging out and if I get a drink or two in me, and then I start running my mouth and hollering and carrying on—as my dad would say—that destroys my voice. The talking. I avoid it, but I always tune in for a minute or two. Prior to a show, I like to bounce for about 10, 15 minutes before. I’ll do kumite foot drills—like, martial arts, karate. It’s just like jumping rope and stuff, except for me that would be monotonous.

You’re rooted near Jacksonville and there’s such a Southern rock legacy there, starting with The Allman Brothers Band and Lynyrd Skynyrd. Do you ever reflect on your own place within that tradition?

JG: I fit into it, because I’m from the same place, but I don’t fit into it because, to me, they’re the icons. If I sold a billion records and was as big as Elvis Presley, I still would never (fit in) … Funny enough, I flew home yesterday, and I saw Johnny (Van Zant) on the plane. I see him all the time. He’s a road dog. He sings for (Lynyrd) Skynyrd now. Johnny was the first artist I ever saw at a concert. He was opening up for Pat Travers in the Coliseum in Jacksonville … You can’t get anybody that would fit better to sing for Lynyrd Skynyrd than Johnny. They’re a huge influence on me. All of them.

Is there a particular song that you hold really close or you think to yourself, “If I could write something half as good as that … ”?

JG: When we were kids, we weren’t really allowed much to listen to a bunch of rock stuff. A lot of kids weren’t. We were in a church, and they weren’t overbearing about it, but there are a lot of elements of rock music that are more adult, for sure. My sister bought me “Gold & Platinum,” Skynyrd’s double album. And one of my favorite songs by Skynyrd ever is “Simple Man.” Funnily enough, (Skynyrd’s producer) Al Kooper wanted to produce a record with me, that was a while back. (Kooper) didn’t want (Skynyrd) to do that song. (According to Grey, lead singer Ronnie Van Zant lured Kooper outside the studio and then locked him out while the band recorded it). “Simple Man” was a huge, huge one for me. There’s a song called “I Know A Little,” a real quick honky-tonk type tune. I love “Workin’ For MCA,” and everybody loves “Free Bird.” I love “Tuesday’s Gone,” it’s got those Mellotron strings on it. I wore all those records out. And then my sister had a pretty good collection of disco 45s—(The) Main Ingredient, all that ‘70s stuff, which is probably a big influence on me. Those songs by Skynyrd stuck with me the most. “The Needle And The Spoon.” I actually covered “The Needle And The Spoon.” That’s a tough one.

I read somewhere that when you were starting out, you guys played some rough juke joints behind chicken wire—and of course, now there’s a remake of “Road House” to remind us of the glory—is that true?

JG: That was (just) me. None of the people I’m playing with (now) are old enough to have done that. I played in a cover band, a cover rock band. I was 17, 18 years old then, and they just let me in (the bar) because I sang in the band. We didn’t need the chicken wire. Some bands did. It’s almost a classic story of “Road House,” though in this sense that this guy’s got a bar called The Gazebo, and it’s out there off Normandy Boulevard, not far from Cecil Field, the Naval Air Station. Back then, it was still a Navy base. This is the (crowd) combo you’re working with: Clay Hill rednecks, which are mostly my family, they’re rough; outlaw bikers, mixed with some other bikers, the real Outlaws (Motorcycle Club) back in the day; and then Navy guys, everyone called them Squids. Nobody came to see the band. They had chicken wire up, but nobody ever throwed nothing at it like you see in the movies. We knew what to play—you can just look at the room and see what to play. But everybody, all of them, loved Steppenwolf. You could play “Magic Carpet Ride,” you could play “Born To Be Wild,” and you immediately got everybody there to be your buddy. You could play any Southern rock. Depending on who’s there, you could have got away with playing a Hank Jr. song. You don’t come in there and play the new Adam Ant song.

There was one exception. There was a cover band called Brutal Poodle. The guitar player was about 6-foot-9. He was a monster, but the lady that sang, she dressed like Elvira, and she had a bullwhip and everything, and they didn’t need no chicken wire. She did whatever she wanted to, and they would snap to attention.

The cover you designed for “Olustee” sports a vividly colored rooster in full crow. Tell us about your connection to chickens.

JG: I grew up with 60,000 of them. It was at my grandparents’ house. Over weekends and a lot of the summers, I worked in chicken houses. When we moved here, we inherited the chicken coop (from the previous owners), maybe 16 or 17 chickens. There was a rooster, Jim-Jim—that’s what the song “Roosters” is about. (Laughs) I can get deep about chickens. They’re just like human beings. They have personalities. And some chickens are assholes, man. Straight up. Some of them are bullies. You could tell they’re afraid of you, and the more afraid of you they are, the more they want to attack you. Jim-Jim wasn’t like that. He was fully in charge. I never, ever saw him have to fight another rooster until he got beat by a big ole giant rooster that grew up under him … He was just a badass dude.