Legacy of Color: Exploring the Florida Highwaymen’s Artistic Revolution

Remember the legacy of the Florida Highwaymen, their place in the art world and preserving the landscapes of Old Florida.

Doretha Hair Truesdell knows she has more days behind her than ahead of her. But before she leaves this Earth, she will see the Florida Highwaymen recognized in a standalone museum.

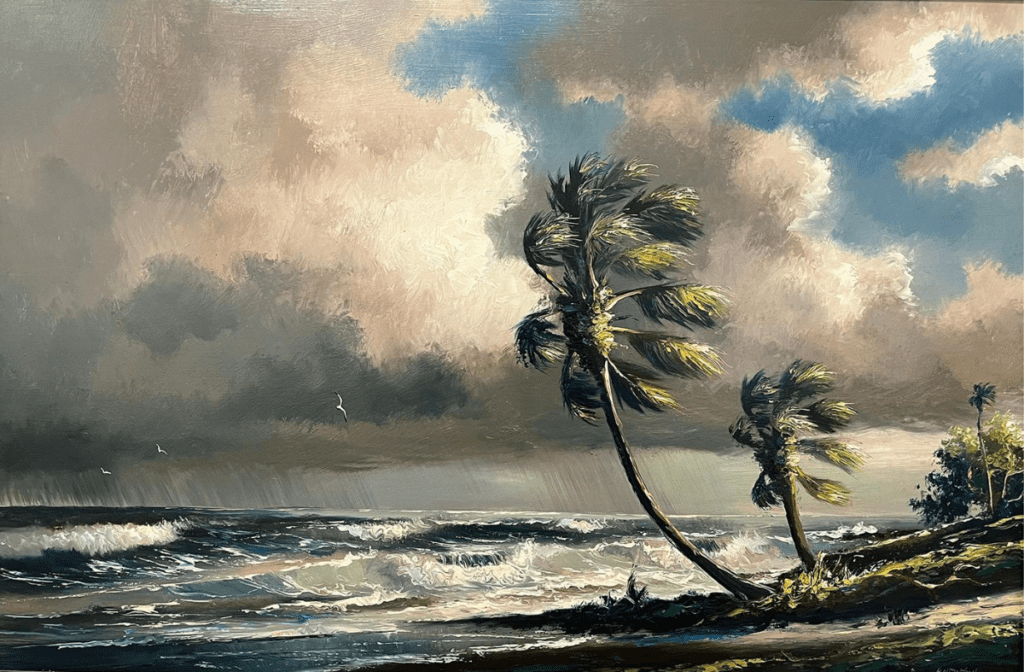

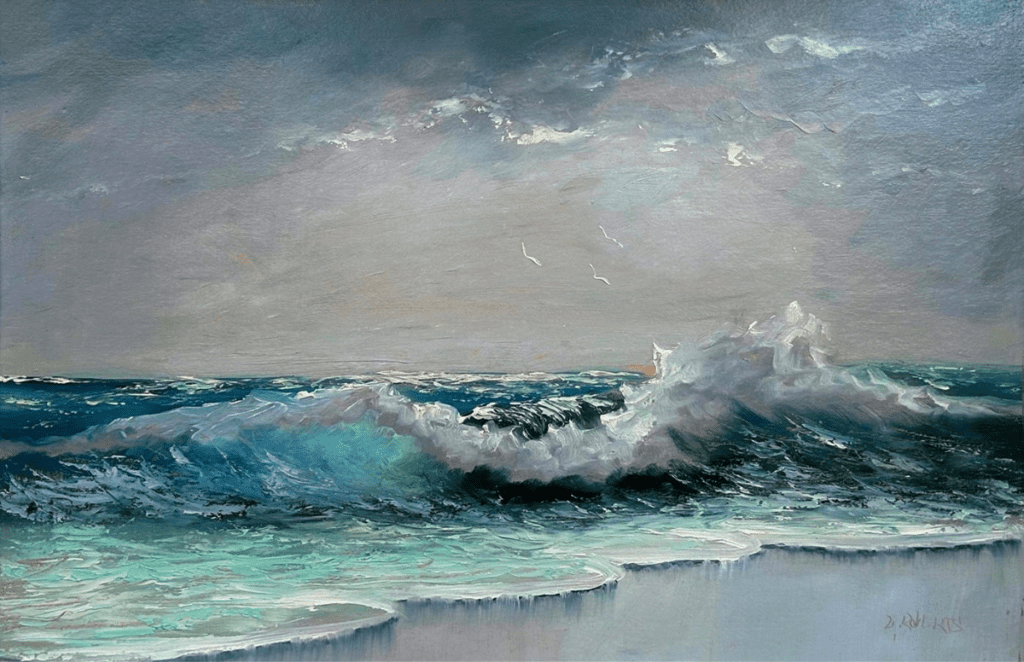

The South Carolina native has spent the last half-century spreading the gospel of the Florida Highwaymen—a collection of Black artists whose oil-based landscapes, seascapes and paintings of Old Florida were sold alongside Florida’s East coast highways in the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s.

“I wanted to finish yesterday,” says Truesdell, who is retired and in her 80s, of the museum. “Time is not on our side—at all. People say, ‘You need to take time for yourself.’ There is no time. It’s now.”

Truesdell is not conjuring a physical memorial alone.

The City of Fort Pierce and the Florida Department of State, through their African-American Cultural and Historical Grant program, have helped fund the renovation of the Jackie L. Canyon Sr. Building in the city’s Lincoln Park neighborhood, which will transform it into a museum celebrating all 26 Highwaymen and is slated to open later this year. The museum’s location is a short walk from the home Truesdell and her husband Alfred Hair, a founding member of the Highwaymen, shared before his death in 1970.

“Time is not on our side—at all. People say, ‘You need to take time for yourself.’ There is no time. It’s now.”

—Doretha Hair Truesdell

Hair was influenced by Fort Pierce-based landscape artist A.E. Backus, whom he met as a teenager in 1958. Backus was a well-known artist who illuminated Florida fauna and waterways with vibrant colors and thick oil for nearly 30 years when he met and tutored Hair.

Hair emulated Backus’s landscapes and then imparted the knowledge on other artists across the state. Outside of Hair and Harold Newton, another Fort Pierce-based artist whom he advised, Backus did not have a direct relationship with the Highwaymen artists.

While Hair was alive, the group of artists weren’t known by a clever moniker, only by their reputation for selling fine art paintings of natural Florida out of the trunks of their cars. The young men sold their works in volume to make a living. Today, these coveted paintings sell for thousands of dollars at auction and in galleries in Vero Beach.

Truesdell recalls Hair sold his art from the back of a Cadillac Fleetwood.

“I think future generations will paint what they see. I know Alfred painted a lot of what he saw,” Truesdell says of her late husband, who died in a bar fight at the age of 29. “He has a lot of ocean scenes and a lot of inland scenes. He loved water. He loved going to the beach. Naturally, it was segregated. Our beach was Frederick Douglass Park. Alfred painted a lot of those scenes from the water.”

Most of the palmettos and poincianas that the Highwaymen are known for painting have been plucked from paradise and paved over by development. The springs and saltwater marshes that inspired men like Hair and Willie C. Reagan are part of an Old Florida that no longer exists and a legacy of Black artists who captured a rare moment in time. And in the two decades since the Highwaymen were inducted into the Florida Artists Hall of Fame, these men—along with Mary Ann Carroll, the only female artist in the group—are rapidly becoming ancestors.

Reagan is one of six Highwaymen still living. His daughter, Joy Gaillard, says it is vital that the legacy of the Highwaymen survives. Once the museum opens, it will expose a new generation to the vibrance and the artistry of the 26 influential painters who chronicled a uniquely Florida style.

“They don’t understand that it was here,” Gaillard says of the natural habitats that inspired the artists’ work. “That’s part of that history of showing them and opening up their eyes to what (Florida) used to look like.”

The surviving Highwaymen are all approaching their sunset. Reagan continues to paint, but not every does.

“It’s very, very important to make sure their legacy stays alive,” says Gaillard, whose father sold his art out of the back of a Volvo station wagon. “To make sure people understand what they stood for, the value of it, understand their hard work, their creativity. That’s the thing that’s important to ensure their legacy stays alive.”