by Carrie Honaker | March 18, 2024

From Devastation to Determination: The Reinvention of Historic Panama City, Five Years After Hurricane Michael

Meet the forces behind the cultural storm surge washing over this iconic Panhandle town

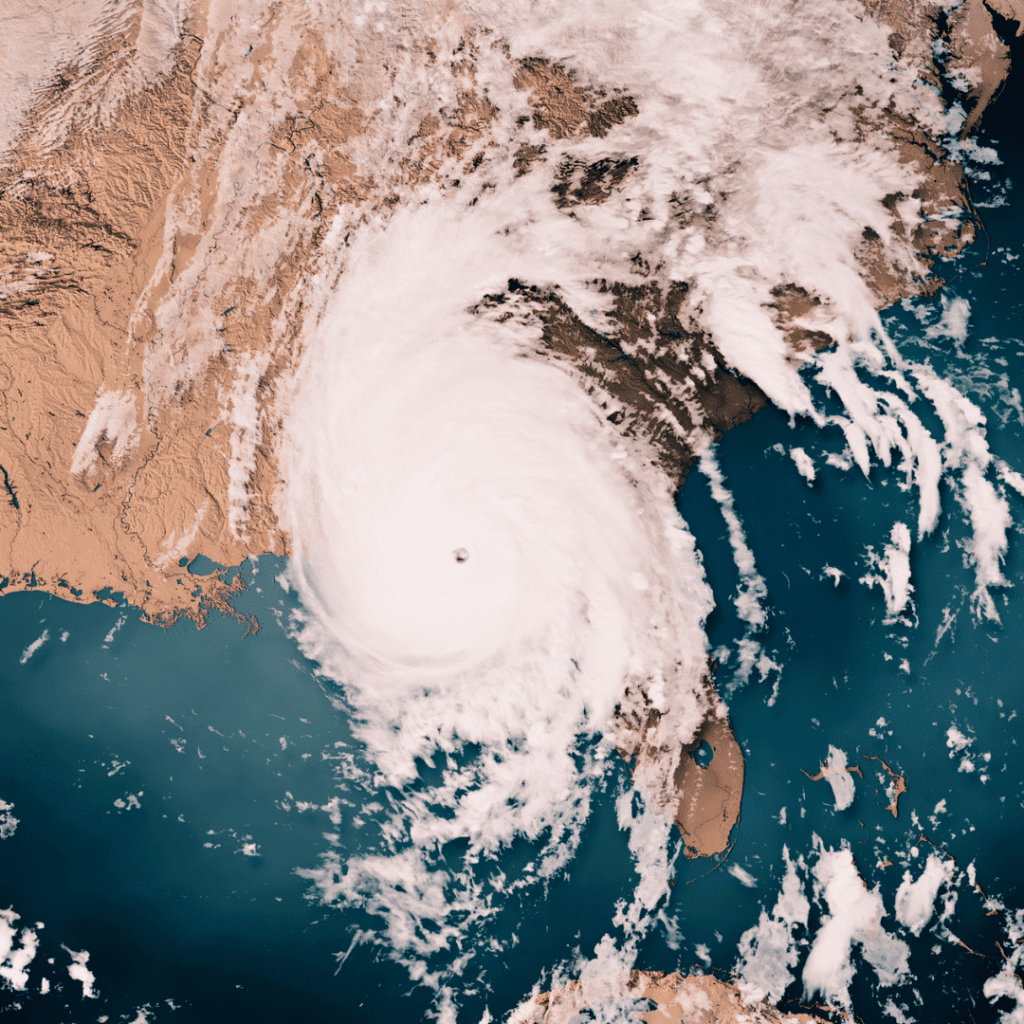

Hurricane Michael tore through Florida’s Panhandle on Oct. 10, 2018, making landfall as a Category 5 storm near Panama City. The violent tempest, with wind speeds up to 161 mph, brought total devastation, ripping off roofs, tossing boats onto shore like toys, unleashing a torrential storm surge and displacing centuries-old live oak trees into once cozy living rooms.

And that was just the landscape. Hospitals shuttered. Grocery stores and gas stations were wiped off the map. A loss of cell service, electricity and municipal water for basic necessities left friends and families isolated and desperate. Survival mode set in, and it stayed for months.

They say only the strong survive, but not even the strong can withstand a Category 5 hurricane. The strong do, however, rebuild, reimagine and restore. And in historic Panama City, a strong few have turned the insurmountable loss into a thriving livelihood that has brought the Panhandle city back—and better than ever.

Kevin Elliott, co-founder and director of Redfish Film Fest, is one of those visionaries. The eye of the storm passed directly over Elliott’s house. “Five houses in my neighborhood just got bulldozed and pushed out to the road,” he said. In the heart of town, Allan Branch, co-owner of History Class Brewing Company (once the town appliance store), remembers seeing a local boat dealership owner driving through downtown with chainsaws and generators two months after the storm. Branch added, “He spent a year cutting trees on people’s houses that they couldn’t afford to take down. He did it for free.”

Amid the rubble and devastation, a new energy started building. Before the storm, change had already begun to percolate in the city’s historic downtown with Branch, Tim Whaler and Dan Magner preparing to open a brewery. Jayson Kretzer, newly appointed Bay Arts Alliance executive director, planned Art on Every Corner initiatives, and Will Thompson was in the throes of setting up Panama City’s Songwriters Festival. Then Hurricane Michael barreled through and put everything on hold, but the people and the grand plans were unshaken.

Visit these places on your trip to Panama City.

Elliott said, “The storm’s aftermath accelerated everything by probably 10 years because people got insurance money to renovate the buildings. Some people who owned these buildings forever didn’t want to fix them, so they sold them to local entrepreneurs, making it easier to start all these plans. The storm also invigorated people in their early 40s to early 50s, like me. We grew up here. We’ve seen the rundown downtown for so long, and now we are in decision-making positions. We’re doing the things we’ve always wanted to see in our town. It helped people reevaluate their lives and decide to do something big.”

On Oct. 10, 2023, a crowd gathered around the century-old downtown clock to watch the ribbon cutting for its restoration. Wagons full of children, pups on leashes and throngs of people lined the street to witness the moment that the clock Hurricane Michael stopped, five years to the day, began to keep time again.

Making Up for Lost Time

Just across the street from the clock, History Class Brewing Company’s tasting room buzzes with conversation and laughter. The wall coverings—a Bay High School letterman jacket, yearbook pages from Rutherford and all manner of post-Hurricane Michael memorabilia—tell the story of the town’s resilience. Magner’s 6-foot-2-inch frame is dwarfed by his deep, full-belly laugh as he pours a perfectly headed pint of Belle Booth Blonde, an ale named after Panama City’s first female postmaster. Also on tap is SeaLab Exp. 638, an IPA that honors the world’s first underwater living facility developed for the Navy at the U.S. Navy Mine Defense Laboratory in Panama City in the 1960s. Another on rotation is Officer Wilson’s Amber, an ale named after Officer “JC” Wilson, who was Bay County’s first Black police officer. Wilson was not allowed to arrest white people and was assigned a car that only drove forward and not in reverse. And now, thanks to History Class, these people and places live on with every pour.

Branch added, “Every town is founded by and cultivated by people who care. Every bridge is named after somebody who cared. Every school, every stadium, every road that has a name is a story of someone who cared about the area, large or small … and the stories get forgotten.” Branch, Whaler and Magner are helping to forge a new version of Panama City on the legends who came before, big and small.

Kitty-corner from the brewery, the 1936 art deco-styled Martin Theatre beckons with some new shine. Two decades ago, the Martin was the only reason to go downtown. Empty storefronts and broken windows revealed the abandonment of Panama City well before the Category 5 beast gutted its tattered remains.

Panama City has long been known as a dying downtown not worth saving, but Hurricane Michael changed that. “There’s not some magic group that makes things happen—that is us. And we realized if we keep waiting, it will never happen. If you want to start a business, you better start it now. If you want to see this downtown thrive, you better start it now,” Branch said.

Great towns remember their stories and protect their buildings. They provide the patina everybody loves. — Allan Branch

Kretzer answered that latent siren call. “After the storm, we checked on the Center for the Arts and found the building damaged, but mostly intact,” Kretzer said. “We looked around, and the landscape was scary. I thought to myself, this is a perfect opportunity to beautify this place with some art.”

The first brushstrokes revealed the “Flutter By” mural on the Center for the Arts, a historic building dating back to 1925 (and was once the city hall). It’s the perfect canvas for the first mural on Panama City’s Mural Trail. Kretzer added, “We chose butterflies as the theme to symbolize the metamorphosis here, coming out on the other side of the storm, transformed.”

But not all was lost. In fact, some old things were found. Another mural, unmasked during the renovation of another building, joins the artistic landscape. A historic Coca-Cola painting honors the city’s past, while the monarch butterflies erupt from their chrysalises, telegraphing a tale of modern-day resiliency.

The newest addition to downtown’s facades includes the vision of local artist Jen Honeycutt, whose 10,925 square-foot-wide painting of bright flowers sprouting from a dying blossom, titled “Growing the Seeds of Change,” captures the essence of the town’s rebirth. Kretzer described the ongoing project, “The murals tell a story about who we are right now. We are passionate and resilient in this community.”

Just across the intersection, the first wall you see behind the historic downtown sign blazes with eight works of art, each painted by a different longtime local artist, including Kretzer, who created the “Ninja Bear” as not only a welcome figure but a protecting force for downtown. And Kretzer has big plans for the future. The small parking lot at the Center for the Arts is now a pocket park, and will host concerts, yoga and projection art installations in the heart of downtown. “We want to bring 3D sculptures, more public art and digital art to enhance the nightlife around town,” he said.

A Town Reimagined

A grant from St. Joe Community Foundation helped Kretzer acquire the equipment to set up an immersive gallery where visitors come check out local art and where the next generation of projection artists can learn the craft. Kretzer also dipped his hand in business ownership in 2023. He opened The Portal, a board game cafe modeled after the wildly popular ones in Europe—customers pay $5 and can play games all day. He has nearly 300 games, signature sodas, candy and even a create-your-own soda bar.

For Elliott, it’s hard to explain the excitement of what’s going on in the historic district. “I look around and go, ‘Oh my god, this is happening. This is really happening,’” he said. A lifelong artist and film festival founder, he needed a charming downtown with big buildings in which to show films and house coffee shops, restaurants and bars for attendees to patronize when not watching films and a nice hotel where people from out of town could stay. He also needed walkability so people didn’t have to drive to enjoy the festival.

“When St. Joe opened Hotel Indigo, that was the last piece I needed, besides years of making friends with downtown businesses to help throw the party,” he said.

With the latest addition, Panama Pedal Tours, which pairs transportation with libations, festival attendees can sip and cycle their way from location to location on a 12-passenger megacycle that doubles as a bar. Beth Klein, co-owner of Panama Pedal Tours, worked in radio for Pell Broadcasting before the hurricane but lost her job when the business was blown away. She returned to her hometown of Dayton, Ohio, to regroup, but Panama City kept calling. Two years after the storm, she returned.

“I couldn’t live in a more beautiful, accessible place. Being here before and then coming back after, seeing how much it’s growing, and being a part of something exciting and fresh, makes me want to stay here. There’s a cohesiveness that wasn’t here before the hurricane,” she said.

Beyond collaborating with local entrepreneurs like Elliott, Klein curates tours that focus on everything from the Mural Trail to historic locations and coffee explorations, and each tour is hosted by local drivers who can explain the route and the nuances of each site.

The renaissance isn’t only about what’s new. Concrete survivors like Ferrucci still serve the same authentic Italian food they have been dishing up for decades while Tally-Ho Drive In, a carhop-service, pumps out juicy burgers and thick shakes the way it has since 1949. And just down the way, Dan-D-Donuts & Deli, a fixture since 1965, still amasses a line that snakes 35 feet to its walk-up window every day.

“Great towns remember their stories and protect their buildings. They provide the patina everybody loves,” Branch said.

A Cultural Storm Surge

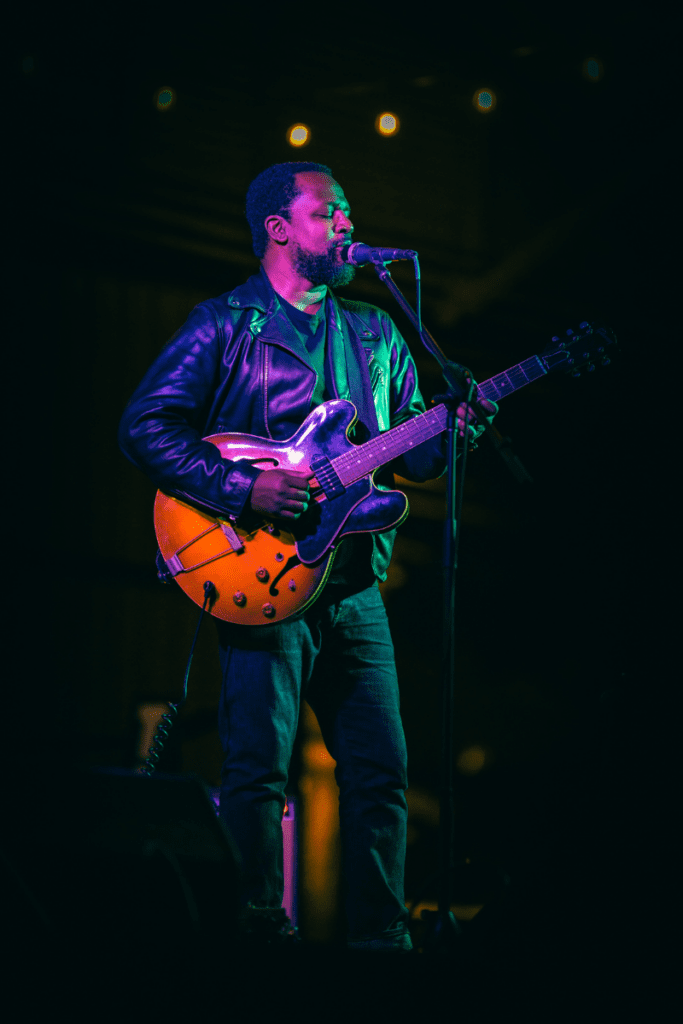

Local musician Will Thompson, founder of Panama City Songwriters Festival and Emerald Coast native, witnessed the town’s ebbs and flows firsthand over the years. A fifth-generation musician, his lineage stretches back through a series of band directors to a relative who played in a 19th-century ensemble. His respect for songwriting led to his founding of the festival in 2018, right before Hurricane Michael stopped the music. He finds talent across the southeast that focuses on telling stories rooted in the region. Tip-bucket proceeds from the festival go to Thompson’s nonprofit, Bay Youth Music Association, where “the long-term goal is to build a YMCA for musicians, a place you can go after school and practice an instrument you couldn’t afford otherwise,” Thompson said.

The first festival was canceled, but it has grown every year since. Thompson saw the phenomena of community building after the storm. “It’s brave to go out on a limb and create a new business or put on a festival. You have to push through the red tape, and that’s always an intimidating factor. You need

permits, you have to jump through hoops, but luckily, we had people just stubborn enough to do it.”

The storm invigorated people in their early 40s to early 50s, like me. We’ve seen the rundown downtown for so long, and now we are in decision-making positions.

— Kevin Elliott

Now, one weekend a year, a half-square-mile section of downtown—which includes a sweaty Downtown Boxing Club, the courtyard between Millies and the Craft Beer Empourium, Elevation hair salon, The Light Room learning space, the Center for the Arts and the street outside History Class Brewing Company—transforms into a regional songwriter’s showcase. Audiences gather shoulder to shoulder, under a blanket of humidity, roaring with applause as musicians keep them rapt hour after hour.

Other festivals and events are adding to the cultural zeitgeist. The Flluxe Arts Festival draws local and national artists who take over downtown to create unique street art. For those looking to escape the crowded French Quarter in New Orleans but still wanting to experience Mardi Gras, the Krewe of St. Andrews Mardi Gras parade and festival just celebrated its 27th anniversary with more than 14 Krewes, 30 brightly colored floats, festive music and tens of thousands of beads and doubloons tossed to a crowd of more than 50,000 people. For the first time since the hurricane, Panama City’s Boat Parade of Lights returned in 2023 with some 24 boats decked out in holiday decor navigating the waters from St. Andrews Bay Yacht Club to downtown and the Hathaway Bridge.

These festivals, and the businesses downtown, will benefit from the newly passed sip-and-stroll Social District. This designated area of downtown is a place, “where you can buy a beer from History Class, walk out the front door with your beer and go shop at one of the retail stores. It’s one more way to enhance the walkability of downtown. Now you don’t have to stay in one spot; you can bring your beverage and check out the murals or go shopping on Friday and Saturday evenings,” Kretzer explained.

When you come to town, you quickly realize Panama City has two distinct downtowns: the Harrison Avenue historic district and historic St. Andrews. Both neighborhoods suffered equal devastation five years ago and are now vibrant hubs of Panama City. They each have bustling Saturday farmers markets and main streets dotted with antique stores, coffee shops and restaurants. Elliott likens it to having two scoops of ice cream on the same cone—each has a distinct flavor but shares the same foundation. He also pointed out, “St. Andrews is the first local Panama City neighborhood you encounter coming from the beach. In a lot of ways, they are a welcome sign to what the real Panama City feels like. There’s Hunt’s Oyster Bar, Uncle Ernie’s on the bay, Sunjammers and all these cool, locally owned places in one of the oldest neighborhoods in town.”

As Elliott says, people want to visit a place where locals like to live. The storm, though tragic, unleashed a surprise surge, one of creativity and culture that continues to inspire residents like Branch, Thompson and himself to build the once small town into the big-idea incubator they’ve dreamed about since they were children. Now younger generations, like Elliott’s daughter, want to settle down here. Branch’s teenagers frequent places like The Portal to enjoy a day of gaming, and young families walk their dogs, meet for coffee and stroll the streets.

“I want to live here for the rest of my life. I want this to be a town my daughter is proud to live in, and I want this to be a town I’m proud to show my friends around. And we’re building toward that every day,” Elliott said.