by Craig Pittman | October 23, 2023

Chad Crawford: The Florida Outdoorsman Turning Passion Into a Powerful Message

Behind the scenes of the latest show by Florida documentarian and TV producer Chad Crawford, who tackles some of our state's most dire environmental crises.

The first scene shows a man with a short white beard and sunburned cheeks driving a boat through the water with tall palms rising behind him.

“My name is Chad Crawford,” he says in a voiceover. “For the past 15 years, I’ve introduced viewers to Florida’s wild beauty.” The screen flashes scenes of Crawford: he’s holding a Florida flag, he’s standing by a canoe, he’s hiking through the woods.

“But right now,” Crawford tells viewers, “the paradise we know and love is being threatened like never before.”

Cue the shots of a massive fish kill amid a toxic algae bloom.

“We are way better than this,” Crawford says in disgust as he eyes a slimy mass of blue-green algae.

This is the opening of a remarkable new six-part documentary series called “Protect Our Paradise,” airing in syndication on television stations around the state and on the Discover Florida Channel this fall.

The series displays glorious views of Florida from the Panhandle to the Keys. It offers stunning footage of panthers, bears, manatees and other seldom seen creatures, as well as affecting interviews with the people trying to save them—scientists, artists and activists.

It also shows some of the things that are destroying the wild beauty of the state. Viewers will see an excavator gouging holes in the lush landscape, cookie-cutter homes sprawling every which way, roads slicing through formerly natural areas and glops of toxic algae fed by pollution. In the end, the series shines a bright light on our state’s environmental threats, but there is a much darker side that could lead to disaster for many of our habitats if Floridians don’t pay attention to what’s going on behind the scenes.

Part Ridiculous, Part Genius

“Protect Our Paradise” was conceived, co-written with and stars Crawford, a native Floridian. He was born in Sanford and now lives in Lake Mary with his wife and four children. He can’t remember a time when he wasn’t soaking up the richness that wild Florida offers to the adventurous.

“I was raised in a family that encouraged us to be outside and outdoors all the time,” he said. “I was always the kind of person who did a little bit of everything. I did everything you could do in Florida.” That included surfing, fishing, hunting and scuba diving from an early age.

He enlisted in the Navy at 19 and wound up in Antigua, where he took every opportunity to do more fishing and scuba diving. After his honorable discharge, he used the GI Bill to enroll in Full Sail University, where he earned a degree in video and film.

Starting out in the movie industry, he fetched coffee for the crews working on feature films, while making ends meet by running a pizzeria. Once he bought his own camera, he paid the bills by shooting everything from weddings to corporate promotional films. Finally, as he put it, he “got sick of doing stuff for other people.”

Crawford decided what he wanted to do was create a show that would make viewers fall in love with the Florida outdoors he knew so well. He came up with the title “How To Do Florida.”

The objective was simple: show off the state he knew to be “part ridiculous, part genius.” But that left one problem: Who would be the face of the show?

Catch “Protect Our Paradise” on the Discover Florida Channel on the following platforms: Roku, Apple TV, Amazon Fire or on the Discover Florida Channel app, via iPhone or Android. Watch online at discoverfloridachannel.com.

“Over two days, I had 40 people come in and audition to be the host,” he said. “Then my wife said, ‘YOU need to be the host.’” He tried her idea for the pilot episode, “and I realized we could save some money if I didn’t have to pay some teeth-and-hair host.” It would become a successful formula.

Over 12 seasons, Crawford has shown viewers how to catch lobsters in the Florida Keys, surf the waves in New Smyrna Beach and camp in the Ocala National Forest. He has seen plenty of highs, such as reeling in a 440-pound swordfish near Islamorada, and he’s also seen a few lows, such as falling out of an airboat in gator-infested waters.

He ends each episode by urging viewers, “get out and do Florida!”

Around 2018, during what’s become known as the Summer of Slime, Crawford started to realize that some of the things we humans were doing to Florida weren’t good for the state. Eventually he launched a second show called “Flip My Florida Yard,” about how Floridians can create beautiful and environmentally safe landscapes at home.

A Moment of Clarity

In 2018, a toxic blue-green algae bloom covered 90% of Lake Okeechobee and soon spread to both the Atlantic and the Gulf Coast. The bloom, thick as a bowl of guacamole, chased away tourists and anglers with its stench and the waves of dead fish it tossed ashore.

Meanwhile, another toxic outbreak, this time of red tide, exploded along the state’s Gulf Coast, killing still more marine life—not just fish but also sea turtles and manatees.

While the algae blooms are natural occurrences, scientists say they were worsened and prolonged by pollution from farm and yard fertilizers, leaky sewer systems and faltering septic tanks. In other words, human failings were fueling the disaster.

Crawford had been alarmed by what he read in a 2016 report called “Florida 2070/Water 2070.” That report—produced by the smart-growth group 1000 Friends of Florida working with the University of Florida GeoPlan Center and the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services—said that if the state continued with its current trend of rampant development, by 2070, more than a third of Florida’s remaining natural lands would be turned into houses and stores. At the same time, development-related water demand would more than double.

I was raised in a family that encouraged us to be outside all the time … I did everything you could do in Florida.

—Chad Crawford

Crawford referred to the blooms and the report as “my ‘Oh, shit!’ moments.” How could he continue promoting Florida’s wonderful outdoors and never mention the dire threats it faced?

“I’ve gotten to travel and see Florida the way few have, and that gives me an interesting

perspective,” he said. “I wanted to be more honest with my fans.”

That’s where he got the idea for this limited-run series. It would be devoted to detailing the threats facing Florida. His hope would be to galvanize viewers to take action to save their state.

“You should feel the weight of it, the way you feel when something you love is sick and not feeling good,” he said.

To get it on the air, however, Crawford knew he’d need a partner, one who would lend him credibility and access.

Rather than turning to the old guard of activist organizations such as Audubon Florida or the Sierra Club, he went with a newer one—one that was founded by the son of two of Florida’s most famous environmental advocates.

Keeping Florida Wild

One of the earliest environmental battles in Florida was over the Cross Florida Barge Canal. The canal was an attempt by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to bisect the Florida peninsula with a ditch designed to cut the travel time for ships. It had been planned for a couple of centuries, but the Corps began to build at a time when truck traffic had superseded shipping to carry cargo.

A Florida scientist named Marjorie Harris Carr led the drive to stop it, citing the danger to the underground aquifer as well as the rampant destruction it would cause aboveground to the Ocala National Forest and Ocklawaha River. In the end, she won.

Today the former canal route is a 110-milelong recreational trail known as the Marjorie Harris Carr Cross Florida Greenway. It also serves as a wildlife corridor, the first in Florida to have a land bridge across a major interstate that’s utilized by both trail users and wildlife.

Carr’s husband, Archie, was a pioneering naturalist who taught zoology at the University of Florida. A talented writer—one of his short stories won an O. Henry Award—Archie Carr used his scientific knowledge and skill with the written word to draw international attention to the importance of the declining population of sea turtles.

In 1989, Congress honored him by naming a 20.5-mile stretch of Florida’s Atlantic coast the Archie Carr National Wildlife Refuge. That beach, between Melbourne and Wabasso, attracts more nesting loggerhead sea turtles than virtually anywhere else on Earth.

Marjorie and Archie Carr had five children. In 1999, one of them, David, founded what was originally called the Conservation Trust for Florida.

Other national organizations, such as The Nature Conservancy and the Trust for Public Land, try to preserve pristine parcels such as swamps and forests that might become part of the state park system or state forest system. Whereas this new organization would focus on protecting Florida’s working rural landscapes, which includes farms, ranches and timberlands. In 2018, the organization shortened its name to Conservation Florida.

You can’t talk about growth without talking about how our state’s growth policy has changed.

—Clay Henderson

The current CEO of Conservation Florida is Traci Deen, a vivacious, blonde-haired sixth-generation Floridian. She was born in Homestead, where her dad was an Everglades airboat pilot and, she says, the family kept a pet alligator in their apartment.

That wild part of her childhood ended when her parents split up and she went to live with her mom, a bank teller. She wound up in a more civilized area, Coral Gables, but was still that girl who had live anoles dangling from her ears like earrings.

By the time she finished her Florida State University degree and was in law school at Barry University in Orlando, she “knew [she] wanted to focus on nonprofit, public sector law,” Deen said.

One of her mentors steered her toward environmental law, first at Barry’s own environmental law clinic. That mentor was Clay Henderson, former president of the Florida Audubon Society and the Florida Trust For Historic Preservation.

Henderson makes an appearance in every episode of “Protect Our Paradise,” as does Deen. He said of Deen, “She’s the real deal.”

Deen took the post as CEO of Conservation Florida in 2017, and says she finds it quite satisfying. “One of the best feelings in the world is when you’re standing on property you’ve just preserved,” she said.

Watch the teaser trailer for “Protect Our Paradise” here.

Under Deen, Conservation Florida has taken on one of its most high-profile tasks ever: establishing the Florida Wildlife Corridor. The corridor, first promoted by photographer Carlton Ward Jr., consists of nearly 18 million acres of contiguous wilderness and working lands crucial to the survival of many of Florida’s 131 imperiled animals, including panthers and bears.

Crawford collaborated with a team from Conservation Florida in designing each episode of the “Protect Our Paradise” series. The first episode is about the Florida Wildlife Corridor and features Ward and some of his trap camera images shot while wildlife passed by, including a remarkable sequence of a bear scratching its back on a tree.

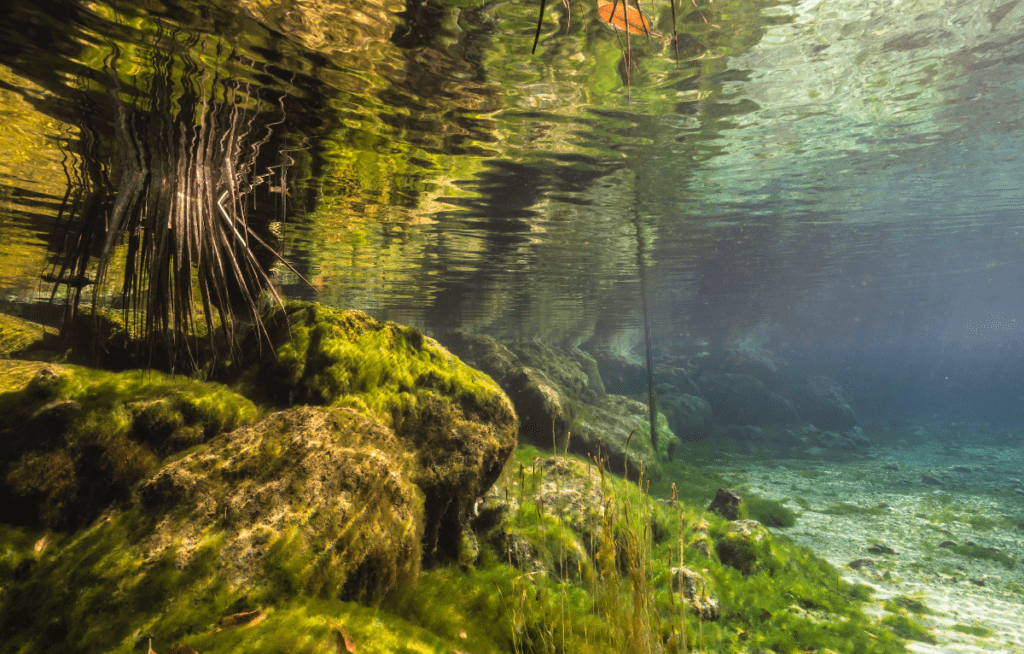

“We could have done a two-hour episode on each topic,” said Deen, noting that each episode was limited to just 21 minutes. They aimed to show Floridians things that few people have ever seen before, such as deep inside a freshwater spring.

“I’d never worked on a TV show before,” she said. “I had no idea how much work goes on with this.”

Making the series took a total of two years from start to finish, with 50 days of production followed by nine months of post-production work, Crawford said.

Henderson, the author of a new book on land conservation in Florida called “Forces of Nature,” shows up in each episode to provide some historical context on what’s being discussed. His portions of the series were shot in a historic home with no air-conditioning.

“My interviews were done in two full days of taping,” he said. “That was eight hours a day under the hot lights. I was sweating worse than Nixon in his debates with Kennedy. They got bags of ice and stuck them in front of a fan to keep me cool.”

A Missing Piece

In addition to highlighting the corridor, the show tackles such issues as water pollution, the coasts, wildlife and the dangers of uncontrolled development. But something was missing.

In 1985, Florida passed the Growth Management Act, one of the strongest and most comprehensive planning measures in the country. The law required each county and municipal government to adopt a local comprehensive plan for growth that was consistent with regional and state plans. It also established a process for the state to approve local plans and amendments, and created a formal state hearing process for challenges to the plans. There would be sanctions for noncompliance, and Florida’s citizens were given legal standing to file a challenge to any changes in the plans.

While the program drew raves from growth management advocates, the development industry disliked it. Developers especially disliked the state agency in charge of administering the law, the Department of Community Affairs. In 2011, just 25 years after its creation, the legislature abolished the Department of Community Affairs and since then has been dismantling the rest of Florida’s growth management system.

One person interviewed for the series episode on growth was Jane West, a former Conservation Florida board member who works as the policy and planning director of 1000 Friends of Florida. She said that in her interview, she named names about pro-development politicians and specified who was responsible for demolishing the growth management system.

“They must have done a lot of editing,” West said.

Crawford said the filmmakers made a choice not to point fingers.

“We steered clear of politics,” Crawford said. “We just did not go there, for the most part.”

“We didn’t want conservation to be seen as a partisan position,” Deen said.

The show says that “bad bills” are allowing too much development that hurts efforts to protect the environment. It never mentions any specifics about the bills or their sponsors.

West says that falls short of telling people the full story.

“You can blame ‘bad bills’ all you want, but if you lift the cover a little more, you’ll see who the bill’s sponsor is and who the special interests are who are pushing them,” West said. “The development community has really got a stranglehold on how our state is growing.”

We need to include the developers in these discussions. It’s all about balancing our robust economy and the environment.

—Arnie Bellini

Henderson, too, said leaving all of that out also leaves Floridians blissfully unaware.

“You can’t talk about growth without talking about how our state’s growth policy has changed,” he said.

Similarly, when the show addresses water pollution, viewers will not hear the names of any of the state’s most notorious polluters, such as the Georgia-Pacific paper mill in Perry. And left out in the show on wildlife: the identity of some particularly destructive developers, such as PulteGroup (formerly known as Pulte Homes), which in 2021 pleaded guilty to 22 counts of destroying gopher tortoise burrows in Marion County (and killing two of the tortoises, which are keystone species and listed as threatened), paying a paltry fine of only $13,700.

Crawford conceded that the shows avoid assigning blame for the horrible conditions depicted in the docuseries.

“We could’ve gone there,” Crawford said, “but we chose to stay neutral.”

Instead, the show takes care in each episode to depict people who are working on solutions.

Viewers see Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium trying to save the coral in the Keys from a deadly disease. There’s a segment on two young guys who are planting seagrass in an area that has none. A concerned citizen in Polk County rallies her neighbors to pass a citizen initiative to pay for buying land for conservation before it can become a new subdivision or office park.

“We wanted to bring more awareness to these groups,” Crawford explained. “This is a little bit of a heroing for them.”

Common Ground

“Protect Our Paradise” cost $700,000 to make, Crawford said. To pay for the production, Conservation Florida connected him with a key donor, and “he loved it and said let’s do it.”

That donor, Arnie Bellini, doesn’t appear in any of the shows, but he’s listed as an executive producer. Bellini started a Tampa-based tech firm, ConnectWise, and then in 2019 he sold it for $1.5 billion. Now he and his wife have become philanthropists with a strong interest in conservation. In fact, the Bellinis were behind Conservation Florida’s successful push to win legislative approval for $300 million in state funding for the Florida Wildlife Corridor.

Bellini said he was glad to help Crawford and Deen design the content and focus of the series.

“We all sat down and talked about what needs to be done,” he said. “What’s great about ‘Protect Our Paradise’ is that it reaches both sides of the aisle,” he said.

Bellini said he isn’t opposed to development, but he wants to encourage the right kind.

“This state’s going to be developed,” he said. “We need to include the developers in these discussions. It’s all about balancing our robust economy and the environment.”

More to Tell

Crawford says he regrets having to leave some things out of the shows.

For instance, he mentions, in the wildlife episode, they had to cut a segment where a biologist “walked around a neighborhood teaching people the right way to engage with wildlife.”

He said he wasn’t happy about having to leave out a planned segment that highlights how the On Top of the World development in Ocala has been conserving water.

And he wished he could have shown more about what’s been happening in the troubled Indian River Lagoon, which suffered such a catastrophic seagrass loss that more than 1,000 manatees starved to death. But overall, he’s happy with the choices made and the shows that have resulted.

The episodes are being syndicated to all of Florida’s major media markets except for the West Palm Beach region.

“It’s a bit of a shotgun blast,” he said.

So far, though, Crawford said he’s hearing nothing but praise for the series.

“The response has been positive,” he said, noting that one fan even said, “Every Floridian should watch this.”

He has plans for more. When the series has finished its run on Florida television, he wants to approach the various streaming services about showing the series nationally.

Then, over the next few years, he plans to repackage the footage into a different form. He wants to make a 90-minute documentary version that could be rereleased in that format and reach a different audience.

“I want to take all the best episodes and put them all together,” he said.

He wants Florida viewers to be more than merely dazzled by the visual artistry of the show. He wants them to see it as a call to arms.

“I want them to be inspired, to be engaged, to be aware,” he said. “We’re such a transient state, but I am hoping to stoke a fire in some people to get involved and be a part of the solution. Because let’s face it, we’re all part of the problem.”