Preserving History One Click at a Time: A Photographic Diary of the Rural Panhandle

Jimmy Nicholson has captured five decades of portraits and images of rural life in the heart of Northwest Florida that go beyond documenting and into the realm of fine art by freezing in time the essence of the American South.

Bright and early on a late spring morning, Jimmy Nicholson fires up the engine of his Chevrolet Silverado work truck outside his Panhandle home in Quincy, Florida. Beside him, he has a trusty, twice-rebuilt Nikon FM2, a 35mm analog camera model last manufactured in 2001. Over the next couple of hours, Nicholson will navigate all manner of back roads and two-lane highways that crisscross his patch of rural Northwestern Florida, a place he’s known all his life yet continues to discover anew.

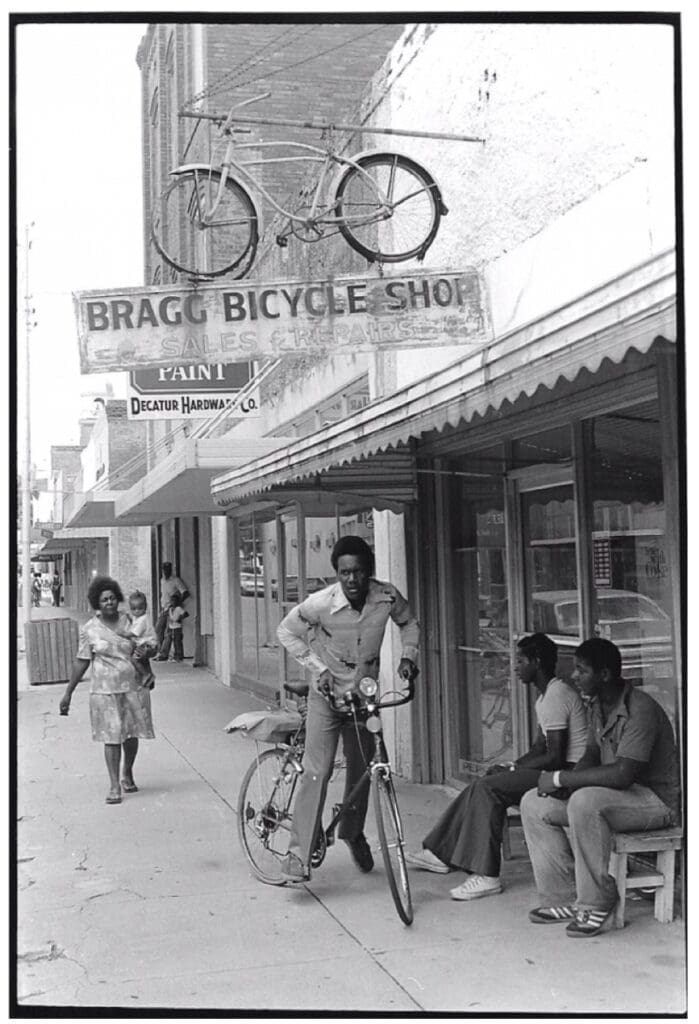

It’s a routine for Nicholson, a former special education teacher. Since his retirement in 2014 he has returned full time to the passion he first discovered as a teenager—photography. The broad-shouldered 69-year-old focuses on the immediate world around him. His black-and-white images capture sunbaked agricultural workers; worshippers at church services and tent revivals; the vernacular signage of pawn shops, small-town groceries, weather-beaten gas stations, juke joints and roving sideshows; country people fishing off riverbanks; and the quiet elegiac stillness of cemetery statuary.

“Pretty much everything I do is curiosity about what’s here,” Nicholson said. “That’s what drives everything. My work is my diary. It’s all of the places I’ve gone, people I’ve met, things I’ve seen. I don’t go out with the intent of creating art. I go out with the intent of creating a literal recording of what I’ve seen. A lot of them transcend to an aesthetic thing, but that’s not my primary purpose.”

Dirt-Road Detours and Making the Ephemeral Permanent

His photographs have appeared in shows at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans and other regional museums and galleries. His works are collected by The Do Good Fund, a Georgia-based public charity that owns an encyclopedic assemblage of postwar Southern photography.

But the work’s wider exposure is via Instagram, where Nicholson has posted over 400 images, he says in pursuit of “making the ephemeral permanent.” The Instagram log is both a tightly curated distillation of thousands of negatives dating back 50 years, and a body of work-in-progress. The array constitutes a historical perspective of this particular corner of the world, one in which time appears to stand still.

What guides Nicholson’s photographic eye is an eagerness to stray off familiar routes, take detours down red dirt roads, ramble neglected pockets of enterprise and see what’s there. Despite the molasses-drip pace of Panhandle life, times do change and even the most familiar landmarks can vanish overnight. “If you don’t photograph it,” he said, “you may not get a second opportunity.”

On this particular day, we’re headed toward Chattahoochee, a town infamous as the site of the Florida State Hospital, a still operating facility that, since 1867, has housed committed patients deemed incompetent for trial or not guilty by reason of insanity. We won’t be stopping in.

Instead, Nicholson pulls into a quiet park—the historic Chattahoochee Landing Mounds by the Apalachicola River, and rolls up next to Victory Bridge. Built in 1922, the bridge used to convey automobiles across the river. It has been unused for decades and only portions of the bridge remain.

Victory Bridge’s foundations are covered in graffiti and discolored by flood lines and mossy grunge. The ground is mushy and scattered with empty beer cans, the foliage laced with clumps of poison ivy. Thick humidity calls forth the dank, fishy scent of the river, while scores of black-headed vultures chatter far overhead.

A Lineage of Photographers and Finding the Ornate

Nicholson drags out a tripod and looks for something with his medium format camera. He finds it in the footing of the bridge and the repeating pattern of the arches overhead, a glimpse of the river in the background. “I’m looking for unique things,” he said. “The ornateness appeals to me. Those bridges were handmade. They have that stateliness about them, that physical presence.”

Nicholson’s process doesn’t end with the shutter’s click. As we climb back into the truck and head out, he picks up a running anecdotal regional history, an expansive narrative of notable floods, details regarding bridge constructions, the decline of once-ubiquitous juke joints and hand-painted signage, the terrible impact of Hurricane Michael—which ripped apart the nearby city of Marianna and decimated the namesake trees in Torreya State Park—and the incredibly complex nature of the tomato industry, which long ago replaced tobacco as the area’s big money crop and now faces an urgent challenge from new anti-immigration legislation signed into law by Gov. Ron DeSantis.

Nicholson isn’t working in a vacuum. There’s a deep lineage of photographers who have traveled the American South shooting work that has come to define a kind of visual shorthand for the region. People tend to think immediately of Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange and their Depression Era travels for the Works Progress Administration. In the 1950s, the Swiss immigrant Robert Frank traversed the country immortalizing in his book “The Americans” a nation of jukeboxes, rodeos, racial and class divides and the lonely gray ribbon of the open road. Later, in the early 1970s, it was Memphis-born William Eggleston who pushed the envelope as he captured everyday sights both banal and beatific in vivid color—once considered vulgar by the art establishment. Alabama native William Christenberry likewise explored color, which helped him articulate the visual potential of rusty tin roofs atop decaying shacks, vacant landscapes and roadside attractions. A generation of photographers followed.

Through the Eyes of the Migrant Worker or Churchgoer

Nicholson was introduced to photography at age 12 when his parents gave him a Polaroid Land Camera for Christmas. A few years later, his path in the Southern documentary tradition was greatly accelerated by his association with Paul Kwilecki (1928-2009), a self-taught South Georgia photographer who ran his family’s hardware store until he sold it in 1975, and devoted himself full time to his photographic practice. He maintained a studio in downtown Bainbridge, and spent five decades documenting daily life and its rituals across the social strata of his native Decatur County. Kwilecki, an intently thoughtful man whose work exhibited a compassionate bond with his subjects, took on Nicholson as a student in 1976. At the time, Nicholson was newly graduated from Florida State University and living back in his hometown. “I had a total transformation,” Nicholson recalled. “He was probably the most influential person in my life. He altered how I saw everything in the world.”

Kwilecki loaned Nicholson books from his collection, and encouraged him to study the work of great photographers—Evans, Berenice Abbott, W. Eugene Smith, August Sander, Lee Friedlander, Diane Arbus, Henri Cartier-Bresson—and then come back to talk about them.

Kwilecki would critique Nicholson’s work. “Very little of it was technical,” he said. Instead, there were fundamental questions: Why are you making these images? What are they about? “He was teaching me how to see in a way I didn’t see previously. It was a world-class education.”

If you don’t photograph it, you may not get a second opportunity.

—Jimmy Nicholson

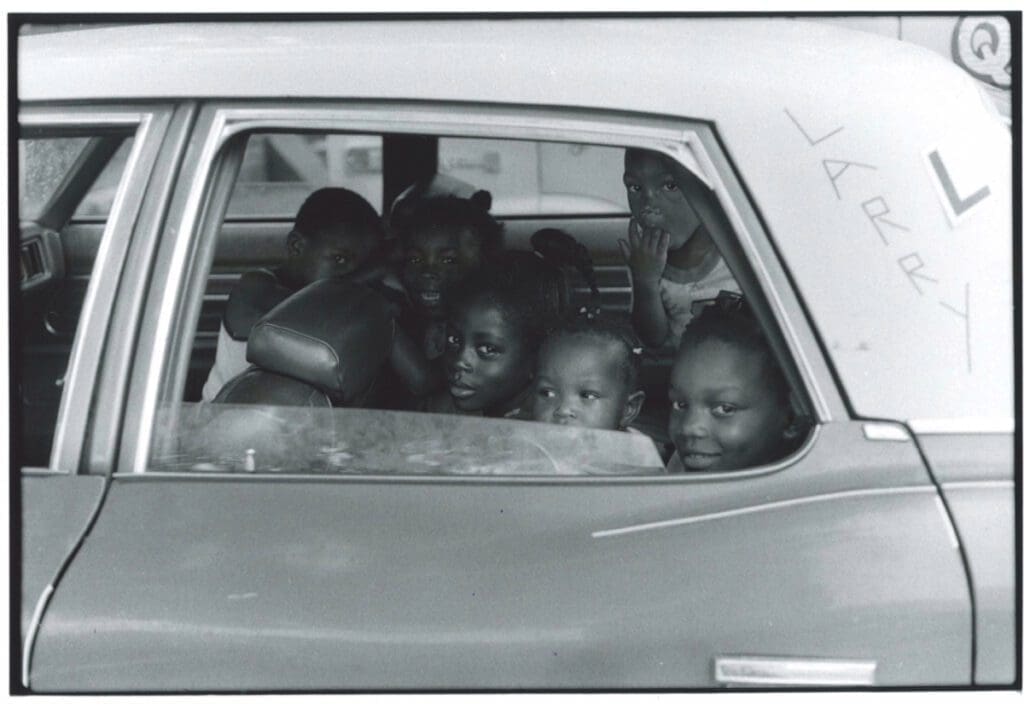

Alan Rothschild, founder of The Do Good Fund, aligns Nicholson with the tradition of Southern photographers that are in the organization’s collection, a tradition “of documenting a way of life in the South that has been in slow decline since World War II, including farmers, mill workers, fishermen and miners, and the structures that supported these traditional trades for more than a hundred years,” he said. “Yet Nicholson’s work has an authenticity, an empathy for the subjects he photographs, that goes beyond documentation. And this respect shows when you spend time with his work. Look in the eyes of the migrant worker, churchgoer or fisherman, and you’ll see it. To me, that reverence to a place—North Florida and Southwest Georgia—and its people, is what makes Nicholson’s work so special.”

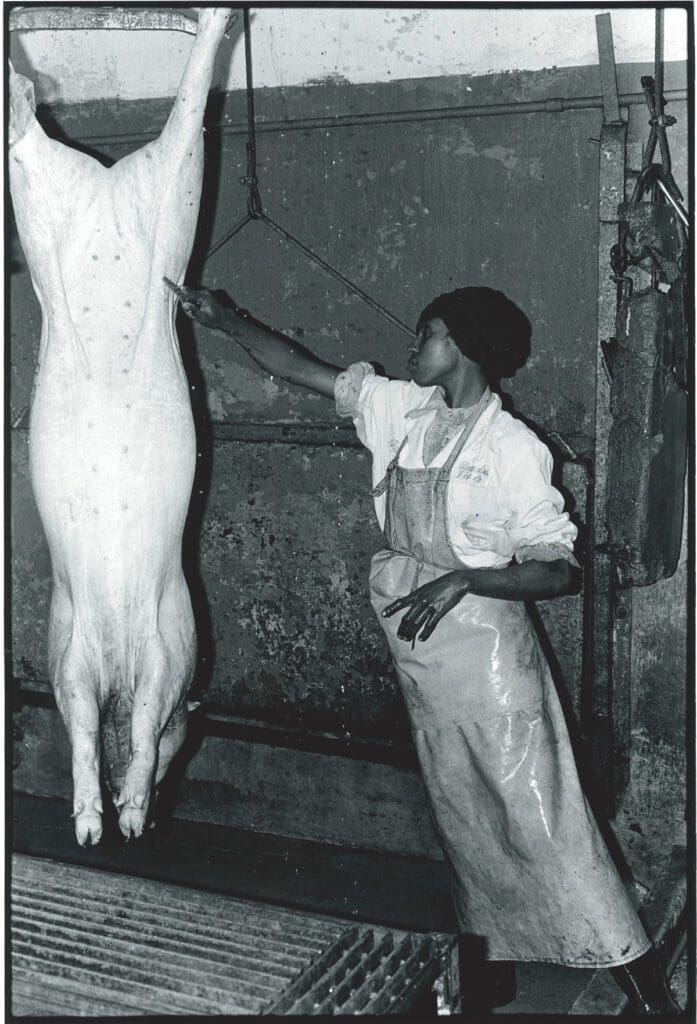

That foundation is evident even in some of Nicholson’s earliest photographs. One of his most memorable is of a young African-American woman preparing to gut a hog as it hangs upside down at the Tillman Brothers Meat Packing Company in Bainbridge. The year is 1977. Nicholson worked at his father’s grocery store which did a lot of business with the local commercial slaughterhouse. They were happy to give him access. “I don’t think today you could even get near a slaughterhouse,” Nicholson said.

Capturing Grace and Sheer Physical Exertion

What resonates in the image is not the abattoir setting so much as the grace displayed in the worker’s almost classical posture as she stretches toward the stark white body of the pig, knife at the ready. The calm, devotional cast of her face suggests she might otherwise be gazing at a flower or a cross. “The position of her hand and the way her body extends outwardly, it’s almost like she’s a ballet dancer,” Nicholson said. “I call her the nun, because of the contrast of her black and white clothing. But she has that same kind of beauty in her body’s position. A lot of times what attracts me to people is how they move.”

Nicholson’s photographs of agricultural workers, which comprise a significant portion of his work, address both the dignity of the laborer and the hardship of their task. “These are people that are marginalized in many ways, and these are jobs that the average American would not ever want to do,” he said. “The sheer physical exertion … the oppressive humidity. It’s a high-pressure job. You work by the bucket.”

The new legislation, in effect since July, has triggered “a mass exodus,” of workers fleeing the state. “Every aspect of tomato farming is hand labor,” Nicholson said. “The law’s going to have a major impact. I’m trying to document it before it all turns south.”

To me, that reverence to a place … is what makes Nicholson’s work so special.

—Alan Rothschild

Despite the contemporary backdrops in his portraiture, Nicholson tries “to just make it about the person, and not necessarily include a lot of context that would relate to time.” As we sit, on another morning, in his living room Nicholson has placed a print of a contemporary tomato picker alongside his 1970s portrait from the slaughterhouse. “They’re made 40 years apart, but you wouldn’t know that.”

Rothschild likens Nicholson’s photographs, especially those taken after he retired from teaching, to a visit home after being away for two decades. “The Black field workers of Paul [Kwilecki’s] day were now various shades of brown—Haitian, Guatemalan and Mexican. The fishing docks and seafood processing buildings that once defined Apalachicola’s riverfront, now frozen in time, abandoned like the way of life of generations of watermen along the upper Florida coast,” Rothschild said.

Death, Dying and the Deeper Meaning

Time’s passage is perhaps most clearly marked in the cemeteries and graveyards that are some of Nicholson’s favorite places to explore. Our brief sojourn by the Apalachicola River is bracketed by visits to a pair of cemeteries. The first is the Union Burying Cemetery in Chattahoochee. Many of the graves appear neglected or wind-damaged, some markers or stones bear hand-scrawled inscriptions to memorialize the interred. In one corner we discover something tragic and oddly celebratory, an infant’s grave, festively arrayed with little American flags and other patriotic emblems. “I take a lot of pictures of children’s graves, they’re very poignant,” Nicholson said. “I’m curious about how [the parents] deal with that grief and how they put memorials around the grave. That was fitting for the 4th of July or Memorial Day.”

Nicholson’s fascination with cemeteries is rooted in a couple of inspirations. At FSU, he took Sally Karioth’s celebrated course on death and dying. His project was a series of cemetery photographs. He then discovered the work of Eugène Atget, the 19th-century French photographic pioneer whose studies of garden statuary captured his imagination, and later Eudora Welty’s work in the field. “The closest thing we have to really formal gardens are cemeteries,” he explained. “And I’ve found there are just a million things to learn by going into cemeteries—and [there are] just beautiful objects.”

Tricia Collins, a longtime Tallahassee resident who pioneered New York’s East Village gallery scene in the 1980s, is a fan of Nicholson’s work. She reflected on a circa 1980 photograph of four adults and a baby fishing on the banks of Flint River, their bodies turned in postures akin to those of classical sculpture. A patch of reeds rising before the glassy surface of the water.

Sometimes the subject is larger than the picture.

—Tricia Collins

“Sometimes the subject is larger than the picture,” she said, thinking of Nicholson’s works. “Sometimes the subject seems opposed or incompatible with beauty. Sometimes the subject is the commonplace, the overlooked. Sometimes the subject is graphically dynamic with a formal beauty, resonant with the ordinary—with an image that is direct and transcendent. And some days the fish are biting.”

For Nicholson, this modest North Florida terrain is as abundant as the whole wide world.

“You can spend several lifetimes investigating a single place,” he said. “There are photographs to be made anywhere you go. You don’t have to travel to the ends of the earth to do it.”

About the Author

Steve, a Tallahassee native and Flamingo contributor since 2017, has written about film, music, art and other popular culture for publications including The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, the Atlanta-Journal Constitution, GQ, and The Los Angeles Times. He is the artistic director for the Tallahassee Film Festival and writes a monthly film newsletter for Flamingo, Dollar Matinee.