by Nila Do Simon | May 15, 2023

Ocala Levels Up in the Fast-Paced Equestrian World

The World Equestrian Center in Ocala brings a new standard of luxury to Central Florida's horse hub.

On an unseasonably warm Saturday afternoon in February in north Central Florida, Sailor, a handsome Oldenburg in his prime, stands basking in air-conditioned bliss. Above his tightly braided mane, a ceiling fan rotates, circulating the air as he steps off his personal mattress onto the stable’s matted floor. Sailor, whose show name is MTM Waypoint, waits perfectly still while being groomed and tacked up by the loving hands of his rider Coventry Burke Berg, who sees him not just as an animal, but as an extension of herself and her athletic dreams.

Like the hundreds of other amateur and professional riders, along with thousands of horses, who have descended on Ocala’s World Equestrian Center for a 12-week series of hunter/jumper competitions, Berg has arrived at this moment by way of a lifelong love of riding.

“If you haven’t met a crazy horse person, you probably are the crazy horse person,” Berg jokes, repeating a widely accepted sentiment that horse people are nothing if not passionate about their sport and their animals. It’s a lifestyle, not a hobby, and one that is flourishing in the heart of Florida thanks to the creation of the World Equestrian Center, where passion and perfectionism collide.

Here in the stables of WEC, as it’s known, horses are king. They and their riders rule this land, which features wide-open space to roam and train among canopies of live oak trees dripping with Spanish moss, the picture-perfect backdrop for such a royally rewarding pursuit.

For professional riders like Will Simpson, who has won more than 75 Grand Prixs (the highest division in the sport which regularly features $100,000 in prize money), WEC is “a game-changer.” And, after one afternoon meandering around the property, it’s easy to see why.

Opened to the public in January 2021, the pristine facility on 378 acres of rolling hills and rich limestone soil offers an array of horse-related amenities for Olympic-level and amateur athletes alike. Highlights include nearly 3,000 stables—2,300 of which are climate-controlled (the most notable modernization to anyone familiar with the Florida heat and humidity)—and two multipurpose expo centers, which regularly host galas, symposiums, charity events and even volleyball tournaments.

There’s also WEC Stadium, a 7,000-seat facility with bright lights that spotlight the manege during Saturday night Grand Prix shows and two video walls that project the live show with crystal-clear imaging. The facility is so grand that Simpson says when he and his horses walk down the ramp to enter the arena, “we feel like we’re playing at the Super Bowl.”

Ocala’s deep history in equestrian culture has put it in the same conversation as historically recognized locations of Lexington, Kentucky and Middleburg, Virginia. In some circles, it’s eclipsing Wellington as the state’s prime equine destination. And now with the draw of WEC for international horse competitors, Ocala has been vaulted to a global stage. Is the quaint Southern town of 65,000 residents ready?

Change of Pace

If anyone can appreciate the ultra high standards that WEC is bringing to Ocala, it’s a competitor like Simpson. In 2008, he was part of the U.S. Olympic jumping team that took home a gold medal, a highlight of his nearly four-decade career. WEC holds a special place for Simpson, who moved from Thousand Oaks, California, to Ocala in 2021, lured by the Florida city’s easy pace and WEC’s potential impact on the sport.

“It was never on my radar to move to Ocala,” Simpson says from his 23-acre farm where he just finished a jog with his horse, Chacco P. “But the trees, the Spanish moss and the horse farm community won me over. Not to mention how special WEC is.”

For competitors like Simpson, WEC goes above and beyond to ensure the riding community is taken care of and appreciated. Attention to detail goes beyond ensuring there’s enough hay for horses. Individual ceiling fans hang above the padded stalls, which at either 12 feet by 12 feet or 12 feet by 14 feet are said to be wider and roomier than most facility stalls. After completing a round of competition, horses even have the option of indulging in a soft peppermint—a sweet vice loved by most equine creatures—that melts in their mouths.

“My horses love it. They like the footing; they like the stalls. They like being able to show inside if it’s cloudy and rainy, and WEC makes the show so aesthetically pleasing,” says Berg, who lives in Ponte Vedra Beach. “I have a lot of gratitude to be able to have a facility like this in our backyard.”

On the performance level, the five indoor arenas and 22 outdoor show rings, including WEC Stadium, have top-of-the-line footing, or riding surface, of a custom-blended mix of silica sand, felt and fiber to provide enough cushion to reduce injury yet remain stable enough to support a horse’s many movements. The animal’s health is so paramount at WEC that it even includes a 40,000-square-foot veterinary hospital on its property, partnering with the University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine to provide advanced diagnostics and treatment for horses, dogs and cats.

And then there’s the 248-room resort-style hotel, The Equestrian. Opened in June 2021, the $800 million five-level building is the epicenter of the compound, where the world of competitive equestrianism shows off its lavish side.

“Being able to stay at a really nice hotel on property is so unique. I can walk the grounds to decompress from my day and prepare for tomorrow, and I never feel unsafe,” Berg says. “I’ve never been able to stay on property and give my horse a little kiss at night, and that’s something that’s really special to me and something I didn’t know was even a possibility.”

The Equestrian is a favored resting spot for traveling riders, their families and training team, as well as spectators and those curious about the lifestyle. Inside the lobby, riding boots are traded in for Gucci slides, and guests are treated to a display of neoclassical French design as they wander to their next gathering spot.

From floor to 20-foot ceiling, mahogany wood and Italian porcelain cover the lobby, and more than 80 Schonbek Swarovski crystal chandeliers hang from above. The lobby walls are adorned with dozens of brass-framed oil canvas portraits of dogs to unite the idea that horse and hound indeed go hand in hand.

In short, WEC is the Disney World of equine sports, if Disney had dedicated sprawling space for four-legged mammals whose strength and beauty are often unsurpassed. Inside an indoor arena, a dressage rider atop a horse with a tightly braided dark mane pauses in front of WEC’s motto affixed to the wall. In sans serif lettering, the words “Quality. Class. Distinction.” peek out past the rider’s left shoulder, fitting core values to a place that oozes all of the above.

A Dynasty Begins

So how did this mecca to the storied world of equine sports come to be in Central Florida? WEC Ocala is the younger sister to the original WEC in Wilmington, Ohio, created by the late Larry Roberts, his wife, Mary Roberts, and their son, Roby, horse lovers and owners of R+L Carriers shipping and distribution company. Considered the premier show facility in the Midwest, Wilmington’s 200-acre location laid the groundwork and experience to build an even bigger and better Southern facility. The Roberts had a long history in Marion County, buying several acres of land decades ago and turning them into a family home and a farm for raising and breeding quarter horses. By all accounts, the Roberts are not just visionaries in the world of equine sports, but dreamers with the capacity and intent to strengthen horse competitions and the region of Ocala along with them.

Horse culture is nothing new to Ocala, which has called itself the “Horse Capital of the World” since 2007 and earned a registered trademark. Legend has it that in 1916, road builder Carl Rose arrived from Indiana to supervise construction of Florida’s first asphalt road. He began experimenting with limestone, found in abundance in north Central Florida, and soon saw how the limestone-based soil, replete with calcium that strengthens a horse’s legs, would be ideal for raising livestock. He moved to Ocala in 1918 and began buying hundreds of acres of land for breeding racehorses. At the time of his death in 1963, Rose was widely considered the founding force behind 30 thoroughbred horse farms in Marion County. Success on a grand scale came in 1956 when Needles, an Ocala-bred thoroughbred, won that year’s Kentucky Derby.

The equestrian world is as varied a sport as any. There are the more visible events that the casual fan may occasionally see on television, like thoroughbred racing, polo, dressage and show jumping. Then, there are others, like rodeo, hunter jumping, steeplechase, equitation and barrel racing that are only popular in certain regions and communities. Despite their differences, these disciplines feature one common denominator: horse with rider. And at WEC, both two-legged and four-legged creatures are given equal footing.

My dad always said that you build something, and it tells its own story.

—Roby Roberts

According to the Florida Thoroughbred Breeders’ and Owners’ Association, Ocala has more than 75 percent of the state’s thoroughbred farms and training centers, surpassing powerhouse equine communities like Wellington and Palm Beach. Marion County, where Ocala sits, has more horses and ponies than any other county in the nation. In fact, there is one equine for every five people in the county. More than 15,000 thoroughbreds train in Florida, where mild winters, limestone-rich grasses and spring-fed aquifers make it an ideal landscape for the horses to roam and train. The industry generates $6.8 billion annually and supplies about 244,200 jobs, according to the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

And, if WEC Ocala has anything to do with it, these numbers will only grow. In addition to the 378-acre property, there are 300 acres in reserve for future development. Construction is underway on a second on-property hotel, set to open in mid-2024 with nearly 400 pet-friendly rooms, the majority of which will be suites with kitchenettes for longer-term stays. If that’s not enough, WEC bought the over 900-acre Ocala Jockey Club in northern Marion County for $10.5 million in 2021, with plans to restore the cross-country course and develop driving competition courses. While Ocala has rightfully earned the title of “Horse Capital of the World,” with WEC’s addition of the Jockey Club and its Midas touch, the city might consider renaming itself the “Horse Capital of the Universe.”

“My dad always said that you build something, and it tells its own story,” writes Roby Roberts, CEO of the World Equestrian Center, in an email. “So, it is early days yet, and we’ll see what the World Equestrian Center—Ocala will tell us.”

Heaven on Earth

Ocala itself has recently experienced a population boom; partly responsible is the wave of Northerners relocating to Florida, as well as those attracted to WEC’s overall compound, which includes retail stores, seven dining concepts, an upscale spa and an RV park, all on the property. According to a study by U-Haul movers, Ocala is the nation’s top growth city based on the net gain of one-way U-Haul trucks in the past year. U-Haul says Ocala saw a 6 percent year-over-year increase in arrivals and only a 1 percent increase in departures. New residents, like Simpson, find themselves in awe of the diverse offerings in Ocala, from its natural springs to its quaint historic district.

“Since I’ve moved here, I’ve seen restaurants popping up left and right, and really cool wine bars, and other fun places to go,” Simpson says. “And I’m discovering the rivers and springs. I love going out to the crystal-clear waters on a hot day.”

During a recent Grand Prix show in the Winter Circuit, the Grand Outdoor Arena’s shaded stands and grounds were packed with spectators. With free admission to walk around the facility, visitors not historically connected to this sport are able to experience the spectacular Grand Prix, where Olympic-level riders and their horses hurdle over fences approaching 6 feet in height. Outside the manege, families roamed the arena carrying ice cream cones and other treats from Miss Tilly’s Lollipops, a confectionery named after Mary Roberts’ English bulldog. Retirees from the nearby community of The Villages meandered through the aisles of Mr. Pickles & Sailor Bear Toy Shoppe (named after Mary’s Scottish terrier and wirehaired terrier, respectively), no doubt looking for a toy for their grandchildren in the store that gives FAO Schwarz a run for its money. Couples and groups sat in the stands for a Saturday date night, cheering when a horse finished a clean run and audibly groaning when a fence post was nicked by a hoof. For a sport that hasn’t quite earned the same widespread spectator appeal as basketball and tennis, the bustle and excitement was enough to make you think otherwise this Saturday evening.

“The facility is exposing the equestrian sport to a wider audience,” says Justin Garner, the Equestrian Center’s director of hotel and hospitality operations. “I could see couples coming to a Grand Prix show for a date night and having a great meal here. The center is making this all a true sporting event and well-rounded experience for spectators.”

Old Ocala

Prior to showing at WEC, competitors’ primary winter show facility was at Horse Shows in the Sun (HITS) Post Time Farm, about a 20-minute drive north on U.S. Route 27. One of several facilities run by a New York-based organization, the 450-acre Ocala HITS location earned a reputation as Ocala’s go-to venue during the Winter Circuit, usually a 12-week period that takes place from December to March. HITS houses a Grand Prix Stadium that has hosted some of the highest-paying competitions in history, such as the Great American $500,000 Grand Prix and the Great American $1 Million Grand Prix. But in recent years, neglect and mismanagement gave way to disrepair and a tarnished reputation, paving the way for a new investment last year from private equity firm Traub Capital Partners. In October, Joseph Norick came onboard as HITS’ chief customer officer, focusing on refurbishing HITS’ image and customer experience.

“It was a jewel that needed a little bit of love,” says Norick. “And today, we’re looking to add more warmth and to make it feel like home.”

The facility is currently undergoing renovations that will enhance its facade and the experience for both rider and horse. Walking around the grounds today, HITS is nestled in a sea of live oak trees and dirt paths. Both the Grand Prix Arena and Main Hunter Arena were built around a pair of oak trees more than 100 years old and were recently enhanced with premium equestrian surface. Other rings have been rebuilt, and more is in the works after the season ends.

But Norick says HITS’ face-lifts aren’t a response to WEC’s shininess or the sportsman’s appreciation for it. The two venues offer totally different experiences. “HITS is for the real Florida horseman. Look around us,” he says, pointing to the rural landscape and towering trees that stretch as far as the eye can see. “This is where I would want to ride.”

The rest of the horse world is awaiting more details from WEC as it continues to grow and expand its offering into other equine sports. But details are slow to be released, and when they are, it’s with carefully worded messaging and usually through a press release. Curated and edited, WEC’s marketing is as manicured as the lawns and as polished as the shiny porcelain floors.

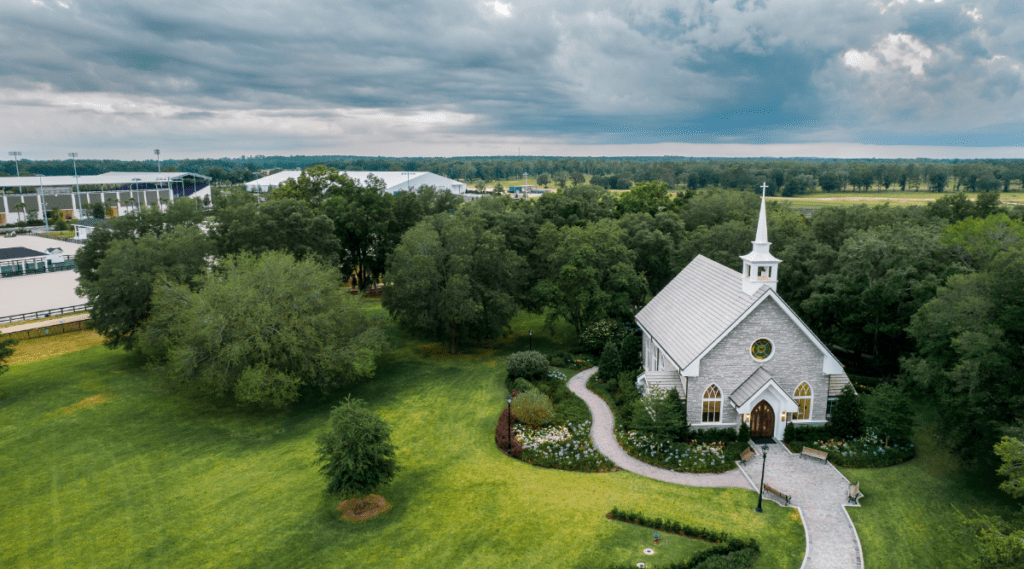

That’s not to say there’s no personality in this neck of the woods. Sitting at the top of a hill on the property is perhaps the most notable vestige of the Roberts family and their Midwestern values: a chapel. The nondenominational, 100-seat stone chapel with stained-glass windows, Swarovski crystal chandeliers and pointed arches has Wednesday and Sunday services in English and Spanish. And if building a chapel on the same property as a world-class sports facility and secular hotel is a headscratcher, then it just takes a little more understanding of the Roberts family to see that what they are creating is one cohesive brand under God. Wooden bowls filled with crosses small enough to grasp in the palm of a child’s hand are found throughout the property, including at hotel check-in, near the on-site restaurants and in the hallways of a hunter show.

While Ocala has been that horse heaven for decades, perhaps now marks a turning point for equine sports, where these prize studs can compete in the Madison Square Garden of show jumping arenas. And if that long-term vision isn’t achieved, at the minimum, Ocala will always be a place for people like Simpson to roam the land with his horses, free and uninhibited.

As he stables his horses after his latest training run, Simpson reflects on his short time living in Ocala. “It’s nice to let the horses unwind and be outdoor horses,” Simpson says. “So it’s kind of nice to come to a slow town and unwind a bit. For me, it’s time to come to a slow town.”

Right on cue, Chacco P. neighs in agreement.