by Jessica Giles | May 9, 2022

In Search of Giants: A New Harvest Leaves Goliath Grouper Hanging in the Balance

Climb aboard a modest skiff in Tampa Bay to cast for a fish shrouded in controversy and confusion.

Drew Brophy loves his fiancé, reeling in monster goliath grouper and Wendy’s Baconators—in that order. Just don’t ask him when he’s hungry.

The 20-year-old Ruskin native has been fishing in the waters of Tampa Bay since he was teetering around the Manatee River as a 2-year-old, and when he’s got a rod in hand, it shows. He’s one of the youngest fishing captains at Poseidon Fishing Charters in Tampa Bay, but don’t let his age fool you. They don’t call him the “Goliath King” for nothing.

“He’s really good,” Hunter Champagne, the owner of Poseidon Fishing Charters, whispers to me as Brophy runs inside to grab more hooks. “And he’s only 20. Just imagine how good he’ll be when he’s 40.”

We’ll need his expertise—and maybe a little luck—this afternoon as the odds are against us. It’s a temperate March day in the bay, and Brophy is pulling crevalle jack from the freezer in preparation for our charter.

“These are our bait,” he says to me, tossing the frozen fish on the deck with a thundering thwack. There are only two things that’ll steal such a sizable bait off our hook in the bay: sharks and Atlantic goliath grouper. And we’re not looking for sharks.

Goliath grouper have been a protected species in both federal and state waters for 32 years. Reminiscent of a refrigerator, these yellowish-brown-speckled marine monsters can weigh up to 800 pounds and stretch as long as 8 feet, making them a coveted catch for trophy fishers. As such, they suffered from severe overfishing from the 1950s to the 1980s, everyone itching to flaunt their leviathan catch. By 1990, federal and state officials feared that the goliath grouper stock was more depleted than previously thought and banned all harvesting of the fish in state and federal waters surrounding Florida. Ever since, it’s been a catch-and-release species only.

Now, the 32-year moratorium is ending. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission voted on March 3 to reopen a limited harvest for goliath grouper beginning in spring of 2023. It’s a pivotal decision for a delicate fishery; one that numerous stakeholders turn to for sport, science and profit. Anglers anxious for this long-forbidden fish will vie for 200 permits that the FWC will raffle off via a random-draw lottery in the fall. Meanwhile, scientists hold their breath for a population they’re not yet convinced has made a comeback.

We’re not fishing for keeps today. In fact, we’ll be lucky if we hook one at all. Normally, when Poseidon Fishing Charters takes clients out on a goliath hunt, they climb aboard Pegasus, a Crevalle 26 Bay outfitted with a surround-sound system, high-tech fish finder and updated navigational technology. With Pegasus, Brophy takes his clients about 20 miles offshore to a wreck overrun with goliath. There, his biggest problem is running out of bait. His record is seven goliath grouper in one day. If they weren’t all more than 300 pounds, he might’ve been able to make it eight.

“It wears you out,” he chuckles, shaking his head.

But as luck would have it, Pegasus blew a gasket this morning, so today we’re running with Themis, an Xpress 185 skiff. She’s adept at maneuvering low tides and shallow waters where snook and redfish play, but Brophy would sooner go vegan than bring Themis all the way out to the wreck.

As we pull away from the modest A-frame house where Poseidon is headquartered, Brophy shows off his brand-spanking-new fishing rod equipped with a 50 wide Shimano Tiagra reel, Power Pro 200-pound braided fishing line and 480-pound leader with a circle hook. Anglers are only legally allowed to fish for goliath grouper, and all other reef fish, using circle hooks because it reduces the likelihood of accidentally snagging fish by the throat or stomach.

You generally don’t want the fish to be bigger than your boat.

— Hunter Champagne

This will be his rod’s maiden voyage, and I feel a sense of obligation to make it worthwhile, but Brophy has already tempered my expectations. Before the red tide bloom along the Gulf Coast last summer, it wasn’t unusual to find goliath hanging around the range markers that stand like guano-sprinkled monuments throughout the bay. But these gargantuan creatures are highly susceptible to environmental changes, including red tide and cold snaps. These days it isn’t a given that you’ll feel the tug of a goliath when you toss a frozen jack overboard in the bay. And if we do manage to hook one of these coveted creatures, we’re in for the fight of a lifetime.

“You generally don’t want the fish to be bigger than your boat,” Champagne said to me with a laugh before we departed. My eyes glanced around the skiff, taking inventory of the available life jackets.

But Brophy likes a good challenge.

We idle our way through the Little Manatee River, and just as the St. Petersburg skyline peeks over the mangroves, Brophy lets Themis show off. Picking up speed, the skiff skips over the choppy waves like a smooth rock, my blonde hair pulled back in a ponytail rippling like a flag. Brophy leans down and shouts over the waves and wind.

“Now when we catch one, we’ll be legendary.”

A Contentious Compromise

Atlantic goliath grouper used to be found from North Carolina all the way down to Southeastern Brazil, and from Senegal to the Congo off the coast of West Africa. Nowadays, it’s rare to spot one of these colossal fish anywhere in the Caribbean, and they’ve all but vanished from the eastern Atlantic.

But Florida has given them a fighting chance. Closing the fishery for the past 32 years has provided enough protection for the species to begin to see some recovery, but just how much is a serious point of contention—and it isn’t as simple as rounding up all the goliath for a head count.

Despite being under close scrutiny for so many years, goliath grouper remain somewhat of an enigma to scientists. Chris Malinowski, now the director of research and conservation at Ocean First Institute, has studied them since 2010 and conducted extensive research into their life cycle, spawning behaviors, diet, vulnerability and mercurial toxicity as a Ph.D. candidate at Florida State University’s Coastal and Marine Laboratory. Alongside former Marine Lab Director Felicia Coleman and former faculty member Chris Koenig, the team has been closely tracking the health of the goliath grouper population for more than a decade.

“It’s hard to say how the population is doing right now,” Malinowski says. “They’re subjected to all kinds of things that are not easily quantifiable or have not been quantified in many ways.”

For most fish species, traditional stock assessments—the collection of demographic information—are done using data collected from fishery catch, Malinowski says. But since the goliath fishery has been closed for the last 32 years, there is no data available from recreational or commercial harvesting.

Scientists tried three separate times to submit traditional stock assessments for goliath grouper beginning in 2004. All three were rejected during peer review and deemed unsuitable for use in federal management of the fishery. These attempts at quantifying the population were rejected primarily due to the persisting unknowns surrounding goliath, according to a May 2021 FWC report.

“Given the data-poor nature of this fishery, it is difficult to assess the status of the stock and objectively evaluate whether the population is rebuilt,” reads a December 2018 FWC report.

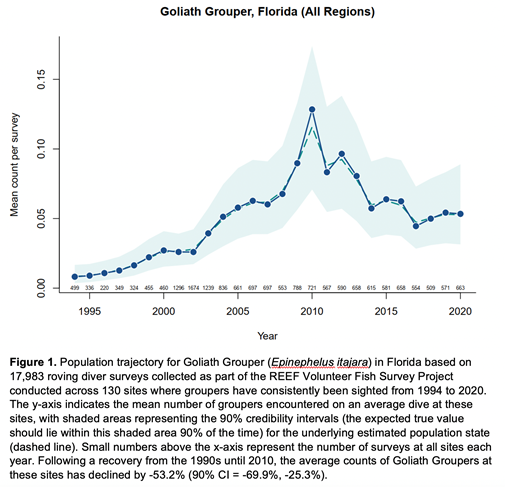

Without the traditional stock assessment, the FWC relies on other sources of data to make decisions about goliath management, including the Marine Recreational Information Program (MRIP), The Everglades National Park creel survey and the Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF), FWC spokesperson Carol Lyn Parrish wrote in an email.

“The problem with those data, which are not being represented and presented well to the commissioners, is there’s a huge level of uncertainty surrounding those lines and curves they show in those data. There’s huge uncertainty. So you don’t use those as if they’re the Bible in this case,” Malinowski says.

Noticeably absent from the graphs used in the last several FWC presentations about goliath grouper management for commissioners? The margins of uncertainty.

“Uncertainty is high in the data we have for many marine species; however, that does not mean we cannot use scientific principles and professional judgment to inform decisions in the face of uncertainty,” Parrish wrote in an email.

The other puzzling component of this fishery debate is the propensity for everyone to see the data entirely different. Malinowski looks at the REEF data and sees a declining goliath grouper population since 2010. The FWC looks at it and sees an overall increasing population. It seems someone is making the data beat to their own drum.

In March, the Commission used its professional judgment to reestablish a limited fishery, to the disappointment of numerous non-state scientists and the elation of frustrated anglers. The approved harvest is an attempt to appease the masses: allow access to an elusive fish without killing off so many that they can’t recover.

Managers are supposed to proceed with caution, not be cowboys and just want to make a decision, because somebody’s got their ear, and they’re not being transparent about who that is.

— Chris Malinowski

Starting in the fall, Florida residents can pay $150 to enter a lottery to win one of 200 available goliath grouper permits for a season that will run March through May 2023. Non-Florida residents will have to cough up $500 to put their name in the hat. The permits only allow for the harvest of a single goliath between 24 and 36 inches in total length—a far cry from the 400-pound highly sought-after trophy goliath. The slot limit is designed to protect the adult fish, the ones crucial for spawning, and target fish with lower mercury levels so they’re safer for consumption. Goliath of this size are typically still juveniles and found in nearshore environments, like estuaries.

Most of the state is fair game, but harvest will continue to be forbidden on Florida’s East Coast from Martin County south through the Atlantic Coast of the Florida Keys, in the St. Lucie River and its tributaries and Dry Tortugas National Park. For those wishing to score a catch in Everglades National Park, they’ll have to secure a special permit. Only 50 can be taken from the park.

The FWC assures the public that this finite harvest will have a negligible effect on the rebuilding goliath population.

“The basic principles of fish biology, fishery science, and life history theory indicate that this level of removals is extremely small, especially when you consider that it is limited to the juvenile phase of life when both abundance and natural mortality are relatively high,” Parrish wrote.

Malinowski doesn’t share their confidence.

“Managers are supposed to proceed with caution, not be cowboys and just want to make a decision, because somebody’s got their ear, and they’re not being transparent about who that is,” he says.

Goliath Games

“Mr. Goliath, are you here?” Brophy calls into the silence as he lobs the frozen jack into the waves. We’re bobbing beside a range marker, one of the goliath’s preferred hangouts in Tampa Bay. If they’re here, we’ll know in about a minute, tops.

“When you feel that first pull, that’s when your heart starts going crazy,” Brophy says with a smile.

His obsession began with annoyance. Brophy would often be out fishing for snapper or regular grouper when a goliath would swoop in and steal his catch. Eventually, Brophy had enough.

“You know what, I’m going to go buy a rod, and I’m going to catch these things,” he recalls. “Now, I found my new favorite fish to go for.”

His experience with goliath snatching snapper and snook off his line is echoed by anglers throughout Florida. Brian Sanders, an angler based out of a small outpost near the Ten Thousand Islands called Chokoloskee, plays keep-away with goliath often when he’s out fishing near a wreck. In the heat of the day, they’ll take refuge underneath the shade of the boat, which also just so happens to be the perfect spot to snatch Sanders’ catch as he reels it in.

When you feel that first pull, that’s when your heart starts going crazy.

— Drew Brophy

“Sometimes, it’s just like a game to them, and other times they’re really super hungry,” he says. “And when they’re super hungry, you can’t keep it away from them. They will eat it.”

Sanders learned to live with the sometimes-annoying animals, but not every angler is as willing to adapt. It’s one of the reasons some fishermen support reopening the harvest: They’re tired of goliath stealing their catch.

In reality, snapper and regular grouper make up less than 1 percent of a goliath’s diet, according to a May 2021 FWC report. They feed mostly on crustaceans and small non-reef fish, but they are opportunistic. If they spot an appetizing snapper hanging on a hook, they’re not one to turn down a snack.

The FWC has been candid about the fact that this limited harvest opportunity won’t reduce the amount of nuisance interactions anglers will have with goliath, because it doesn’t target the adults. In fact, a byproduct of rebuilding the fishery will be more frequent interactions between fishermen and goliath that result in losing their catch, according to the presentation at March’s FWC meeting held in Tampa.

Today, it seems no goliath are interested in the meat dangling from our circle hook. We zig-zag from range marker to range marker, plunging our frozen bait into the estuary and coming up empty. Having exhausted all of the structures our species favors in the bay, Brophy pulls his buff up over his nose.

“Y’all ready to go fast?” he says.

The Thrill of the Fight

The sun is just beginning its descent when we find ourselves in the shadow of the Sunshine Skyway Bridge. Although he hasn’t said it, I can sense that this is our Hail Mary, our last chance to land what we’ve been searching for.

As Brophy lobs the same tired jack into the bay, a voice calls out from overhead.

“You goliath fishing?” says the man, perched on the railing of the Skyway Fishing Pier, one foot dangling on either side.

“Yep,” Brophy calls back, a smidge of defeat evident in his brief response.

The young captain was eager to spend the afternoon hunting his favorite fish. It’s a charter that feels more like play than work to him. When I asked Brophy why goliath grouper have become such an obsession for him, he can’t control the grin that creeps up his cheeks.

“It’s a pure adrenaline rush,” he says.

For years he underestimated them. He’d go out with a rod he’d use to haul in sharks, and the goliath would snap it like a Kit Kat. Undeterred, he returned with an even bigger one. It’s as if he could hear the goliath taunting him.

When he caught his first big goliath, it was like he won the Super Bowl. The best part is, he captured it all on film.

“Sheeeeesh,” he exclaims in a high-pitched tone on the video as he struggles to surface the fish. “You’re a weak grouper, aren’t ya? You ain’t nothin’ boy!”

When he spotted the goliath’s silhouette floating up to the surface, Brophy lost his mind. He estimated it was around 350-400 pounds; the biggest fish he’d ever caught in his life. And suddenly, it was the only thing he wanted to catch.

Despite their enormous size, Brophy says the fight usually only lasts about three to five minutes. The hardest part is pulling them off the wreck, reef or whatever structure they’ve made their home. Once you get them closer to the surface, they’re bloated, tired bodies float to the top like a balloon.

Anglers are discouraged from pulling goliath grouper into the boat because their bone structures aren’t capable of supporting their weight outside of the water, so many join them beside the boat for a photo op. When Brophy jumped into the ocean to commemorate his inaugural big catch, the goliath got the last laugh, giving the guide a solid slap with its tail. Not even that could wipe the smile from Brophy’s face.

Cash Cows

I can’t help but feel a little envy when Brophy recalls his first goliath catch. I was itching for that rush. I wanted to know what it felt like to muscle up a fish three times my body weight. I wanted to understand the hype. I’m slowly coming to terms with the fact that this may just be a nice afternoon boat ride when Brophy lets out a groan.

“I’ve got something,” he says quietly, a twinge of panic woven in his words.

“Really?” I squeal.

“I’ve got a feeling it’s a dolphin,” he says.

My excitement extinguishes. It’s not often that a dolphin accidentally snares itself on the hook while Brophy is out goliath fishing, but it wouldn’t be the first time. An inquisitive bottlenose had been circling our skiff a few minutes earlier. Sure enough, Brophy spots its dorsal fin at the end of his line.

Luckily for him, the dolphin doesn’t stick around long. Before Brophy has to hatch a plan for safe removal, the dolphin lets go of its grip on the bait.

“Oh, thank God,” Brophy exhales.

Even this catch-and-release fishing doesn’t sit right with some people when it comes to goliath grouper. Malinowski has a folder full of images of mangled goliath grouper with their throats ripped open, eyes missing and other severe injuries due to mishandling during catch-and-release.

Members of the dive industry are particularly averse to the practice of parking on top of shipwrecks and reeling in one monster goliath grouper after another. These are their cash-cow destinations. Gerry Carroll, the owner of Jupiter Dive Center, argues that the repeated catch-and-release of goliath grouper on shipwrecks is really just catch-and-kill, like shooting fish in a barrel, he said during the FWC meeting.

Goliath grouper use shipwrecks off the coast of Florida as their spawning sites. From late July to October of each year, dozens to hundreds of goliath grouper gather on artificial reefs and wrecks to form spawning aggregations. Outfitters, like Pura Vida Divers in Riviera Beach, capitalize on this spawning season by taking divers from all over the world out to witness this spectacle found in few other places on earth. Revenue from the dive industry has tripled over the last five years, according to FSU’s Coastal Marine Laboratory, an uptick many credit to an increased presence of goliath grouper on offshore and artificial reefs.

We are not lobbyists. We are not being paid to be here. We are doing this as a labor of love, because we are the resource users who have a vested interest in the perpetuity of this species.

— Shana Phelan

Since goliath grouper are the main performers behind this profitable show, it’s no wonder that numerous dive shop owners fought vehemently against the proposed harvest, especially considering divers reported smaller spawning aggregations last season than previous years.

“We are not lobbyists. We are not being paid to be here,” said Shana Phelan, co-owner of Pura Vida Divers at the FWC meeting. “We are doing this as a labor of love, because we are the resource users who have a vested interest in the perpetuity of this species.”

Although the FWC passed the proposed harvest, it did advise staff to look into increased protections for goliath grouper at known spawning sites, including the potential for banning all fishing at these locations during spawning season.

Just the Beginning

With sunlight dwindling and all of our options exhausted, we’re forced to accept that there will be no goliath today. As we tear back through the bay toward the mouth of the Little Manatee River, I can’t help but wonder what our zero-catch day means. Was it just bad luck? Or is this the manifestation of what scientists have been trying to tell the public all along?

The answer, like everything else about this species, is murky. Until more research is done and gaps in the data are filled, no one can say with absolute certainty what a reopened harvest will mean for goliath grouper. Malinowski worries that we may not fully understand the ramifications of the limited harvest until it’s too late.

“The fear is, from my standpoint, that this opens up a gateway to the next thing, which would be the adults,” he says. “I don’t think it ends here.”

And given the public comments made during the FWC meeting where the proposal was approved, Malinowski’s suspicions are correct. Some people don’t want harvest opportunities to end at juveniles. Some advocated for spearfishing to be included in the harvest, others urged the Commission to consider a larger slot limit, and multiple people took to the podium to praise the commissioners for “taking a step in the right direction.”

Despite goliath grouper being one of Brophy’s three greatest loves, he doesn’t really care whether the limited harvest is approved. Most of the goliath he lands don’t fall within the slot limit anyway, he says, and he feeds off the fight of the big ones.

He wouldn’t mind taking out a client in search of a smaller goliath if they were able to score a permit, but, as for himself, he won’t be shelling out the $150 for his own.

“Why not?” I ask. Brophy chuckles.

“I’m allergic to fish.”