by Moni Basu | November 1, 2021

Drivin’ the Dixie Highway: How Florida’s Dream Road Turned to Dust

Dixie Highway may one day lose its name, but the town it left behind tells a story of little-known Florida.

Last year, before the pandemic stole our way of being, Flamingo sent me to South Florida to report a story about veterans. As I made my way to Lighthouse Point, I found myself snarled in traffic at a busy intersection. I looked up to see a road sign that made me sit up and take notice: Dixie Highway.

Perhaps I should not have been surprised. I had, after all, spent most of my formative years in the South. My father began teaching at Florida State University in 1975, and I realized quickly, in my Tallahassee school, the impermeable chasms that existed between Blacks and whites, even though we never spoke of them in any of my classes. My social science teacher was a white woman who changed my brother Shantanu’s name to Bob so that she could pronounce it more easily, hardly a woman who taught us a true history of the South. In her defense, no school curriculum likely included Black or indigenous history back then.

I did not learn about the American legacy of slavery and genocide until much later, when, as a college student, I joined the Center for Participant Education at FSU. In the late 1970s and early ’80s, the Center formed a thriving Berkeley-style free school that promoted underrepresented voices of America. I understood then the void in white America’s understanding of the past.

Still, on that recent day in South Florida, I found myself confounded by the Dixie Highway sign. The name was jarring, and equally so was the fact that it still existed amid a bustling Broward County metropolis. At once, the name conjured history and hatred in my mind.

My social science teacher was a white woman who changed my brother Shantanu’s name to Bob so that she could pronounce it more easily…

— Moni Basu

In subsequent weeks, I read about the attempts to remove “Dixie” from the name of State Road 811. Just like Dolly Parton scratched it off an attraction at her theme park, and the Nashville girl band became just the Chicks, and how Dixie State University in Utah decided to change its name, too.

I sense, or rather, hope, it won’t be too long before “Dixie” is gone from Florida. In some places, this expunction has already begun. Back in 2015, a stretch of Dixie Highway in Riviera Beach was renamed President Barack Obama Highway. In 2021, Coral Gables announced its portion of the Dixie Highway would become Harriet Tubman Highway. But before “Dixie” disappears from the names of public places and, with them, our psyches, it’s imperative that we fully comprehend the history of the iconic highway, which today runs parallel to U.S. 1 and Interstate 95 in South Florida. There is a story behind almost every name, and I grew intent to learn about the origins of this particular highway.

Where did it begin? And end? And why that name?

Now, on this August day, as summer defies quitting with the force of the Delta variant, I have arrived at a place that offers explanation. It’s a place that is hard to find, hard to traverse, hard to know. It’s been called a ghost town, but that is not the truth. Ask the 300 or so people who call this place home. They receive mail in boxes adorned with dolphins. Some yards boast Trump signs. One even has an old scrapyard plane displayed as an ornament on a tree. But, yes, it’s a place masked in obscurity, one that warrants only four short sentences on its Wikipedia page.

I have come to Espanola, about an hour south of Jacksonville and 20 minutes west of the Atlantic. This is where faint traces of the past remain, though they, too, are prone to erasure.

The damp air of the morning is as thick as the North Florida scrub pine and palm that surround me. No signs direct travelers to the road I am in search of. Nor do any inform them of its pivotal role in the making of this state.

There is, however, a warning: “Travel at your own risk.” And another prohibiting the removal of the bricks in the road. Doing so, it says, warrants prosecution “to the fullest extent of the law.”

That serves as the only indication, really, of the significance of this road, a stretch of the Old Dixie Highway, the historical precursor to the four lanes of asphalt I saw in South Florida. What exists today is about an 11-mile stretch that runs from Espanola, here in Flagler County, to Hastings in St. Johns County; it comprises the longest remaining part of the original Dixie Highway in Florida. Rightly, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2005.

“It’s one of the oldest roads in America,” historian and author Bill Ryan told me. He also called the lands through which it weaves and winds “the wildest territory you are ever going to see in Florida.”

Folks in these parts of Flagler know it as the Old Brick Road. For good reason. Before me are rows and rows of vitrified bricks, manufactured by the Graves Shale Brick Company in Birmingham, Alabama, belonging to a slave-owning man who fought for the Confederacy. It took 237,600 such bricks to build just 1 mile of road, 9 feet wide. They are the same bricks that paved the streets of St. Augustine.

There is a story behind almost every name, and I grew intent to learn about the origins of this particular highway.

— Moni Basu

“They were practically indestructible,” said Ryan, who also serves as a director of the Flagler County Historical Society, in a brief history lesson he’d given me over the phone.

I see that now. More than a century after they were laid, many of them still lie embedded atop a packed-shell foundation, peeking through the years of dirt and debris that settled once the road was abandoned. I am eager to begin travelling into the woods, into the past.

I stand where the remnants of the Old Dixie Highway end in Espanola and the words of a Rudyard Kipling poem flood my mind:

They shut the road through the woods

Seventy years ago.

Weather and rain have undone it again,

And now you would never know

There was once a road through the woods

True South

Before I headed to Espanola to drive what survives of the original Dixie Highway, I stopped at the home of Randy Jaye, a self-made historian in Flagler Beach. I wanted to learn more about Espanola, beyond how history portrays it as the town that rose and fell with a brick road.

Jaye grew up in Pennsylvania surrounded by Philadelphia, Valley Forge and Gettysburg. Those places, he said, instilled in him a hunger for history.

He had made a go of it for a while in Los Angeles as a business systems functional consultant and moved to Orlando 28 years ago. Eventually, he tired of traffic and tumult in the big city and settled in 2012 with his wife, Linda, in quieter Flagler Beach, where, as he said, he could reclaim a better quality of life. He’s long been retired, and in his spare time, he has taken up the mantle of documenting a past that he fears might be lost forever.

In May 2017, Jaye self-published a history of Flagler County to commemorate its centennial. As soon as it appeared on Amazon, he had a realization.

“It was almost 100 percent white,” Jaye said. “I felt like I missed the boat.”

So, he set out to rectify his oversight with a second book that tells the Black history of Flagler County, a book that examines the county as a microcosm of the segregated South. In Perseverance: Episodes of Black History from the Rural South, Jaye tells the story of the other side of the tracks.

That a white man should write this seemed odd to me. Jaye recognizes his work to be that of an outsider, and later in the day, over lunch at the Chicken Pantry in nearby Bunnell, longtime resident Daisy Henry told me, “It’s a good book, but he didn’t tell it all.”

It was almost 100 percent white. I felt like I missed the boat.

— Randy Jaye

Henry has lived in the same house most of her 74 years. She raised her children by herself, ministered to a faithful flock through Spirit of Truth Outreach and even served on the city commission in Bunnell, a few miles southeast of Espanola.

“You know, the way we were treated and all,” she said between nibbles of fried chicken, apple sauce and French fries.

“You mean how Blacks were treated as second-class citizens,” Jaye replied.

“Oh, no. Way worse than that,” Henry said. “This county here was one of the last ones to integrate. … You have to accept there are some things you can’t change.”

Still, I respected Jaye for trying to tell the story of the place that surrounded the Dixie Highway. Aside from a few oral histories and published interviews with residents of Espanola and nearby Bunnell, very little writing exists that tells of Black life here. Even in many of the historical documents I perused, there is hardly any mention of how America’s new infrastructure affected poor Black families, who often found themselves disenfranchised, discriminated against and in deep debt in a post-Reconstruction South.

“A lot of that history is suppressed to this day,” Jaye said.

He, like myself and many Americans, grew up not knowing the true stories of Florida, of the South: stories of Black and brown experiences in a white-ruled America. The story of Espanola is among them. Jaye’s research was a journey of discovery that turned into efforts to preserve Black heritage.

The Espanola Schoolhouse, for instance, is the last standing one-room schoolhouse in Flagler County. In its time, it was the only school in Espanola for Black children, built by the community with money earned selling peanuts and ice cream, according to the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers. It didn’t have running water or an indoor bathroom, but within its humble walls, Black children could get an education. In the 1950s, some walked several miles from neighboring Neoga and Bimini to attend classes with Essie Mae Giddens, the school’s only full-time teacher, Jaye said.

Essie Mae died in 2003, but her husband, the Rev. Frank Giddens, proudly told me that at 90, he is the oldest person in Espanola. The son of sharecroppers said his parents settled here because it was one of the few places back then where Black people could own land. He was 19 when he helped pour the foundation of the Espanola Schoolhouse.

Many of the area’s Black schools were torn down and no longer stand as reminders of segregation. But the one in Espanola, Jaye said, was privately owned and therefore somewhat protected from county actions.

Jaye succeeded last year in placing the vernacular-style building on the National Register of Historic Places, the first place of Black heritage from Flagler County to receive such recognition. He is currently involved in efforts to raise money for repairs and renovations to the 71-year-old building, which is now home to the St. Paul Youth Center, run by the St. Paul Missionary Baptist Church.

Giddens has lived his long life in a house not far from the Dixie Highway. He was born after the highway had been rerouted but he, like Jaye, can tell stories about Espanola’s heyday a century ago.

During my visit, Jaye suggested we drive together in his red Chrysler. The Old Brick Road is rough—better not to jostle through in my ground-hugging Mini Cooper, I thought. I accepted his offer, and with Linda in tow in the back seat, we made our way to Espanola.

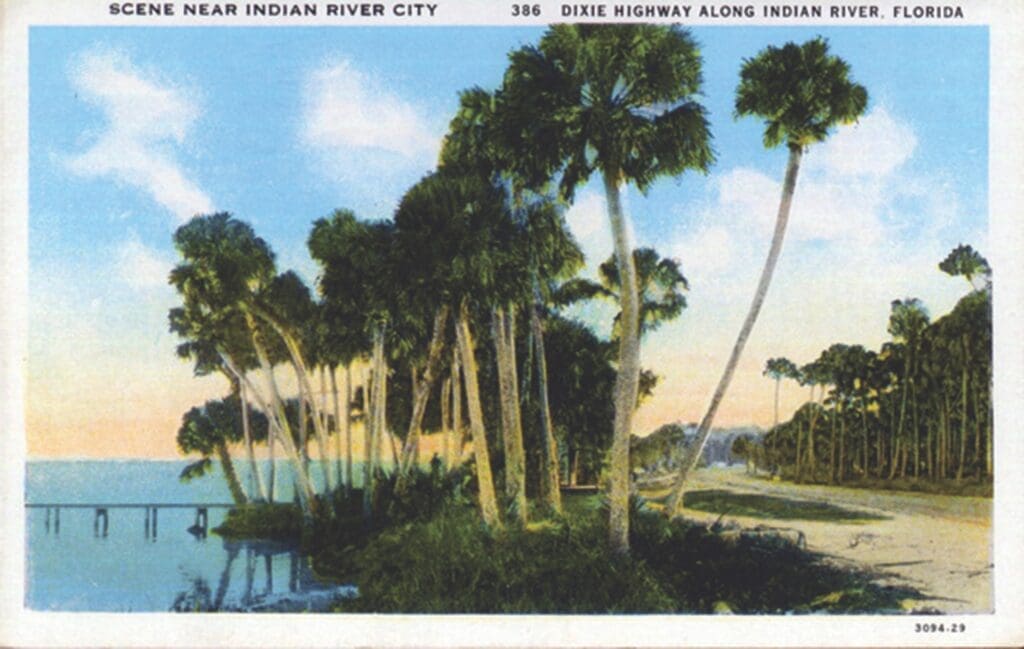

Gateway to Florida

We begin the journey bumpety-bump. Over potholes—blame hulking lumber trucks that hurtle down this historic road—and mounds of dirt and bricks that were baked for three days in an oven and survived a century of neglect. There is nothing around us now but the oaks and the pines and the palms. And the Spanish moss drooping from branches like mourners’ lace.

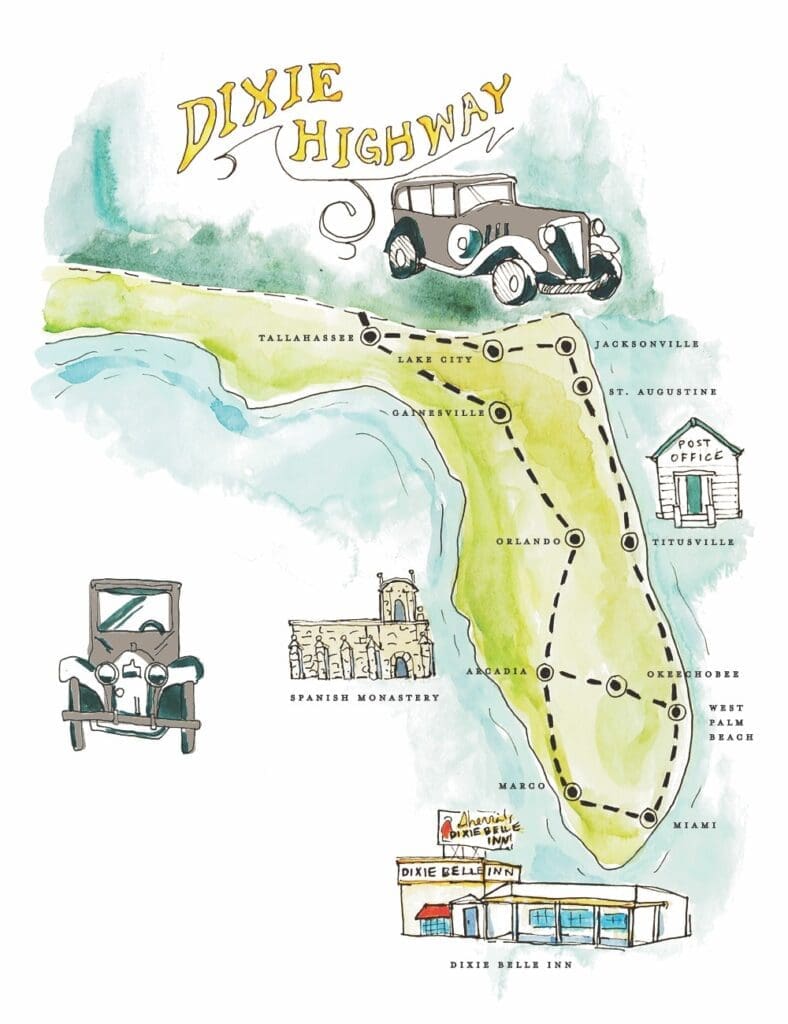

Once, this road connected America’s Midwest to the South, widely known then as Dixie. It wasn’t like the interstate system that eventually made it obsolete, but instead contained a series of local roads that snaked from Sault Ste. Marie, where northern Michigan kisses the Canadian border, down to Miami.

The brainchild of millionaire entrepreneur Carl Fisher, the Dixie Highway was the gateway to Florida when it first opened in 1915. There was an eastern route and a western route through the state in order to connect a larger number of communities. In addition to the Flagler stretch, another small portion of the eastern route still exists today in Maitland as a walking trail around Lake Lily. The original bricks were covered up with asphalt in the 1960s, but uncovered and restored in 1998, according to the historical marker erected there.

They saw not the darkness of Jim Crow but their dreams shimmering in the swamps and surf of the Sunshine State.

— Moni Basu

When the Dixie Highway was completed, more than 5,000 miles of roads wove 10 states together. Some wanted to call it “The Hoosierland to Dixie Road,” according to an article published in The Atlanta Constitution in December 1914. Still others suggested “The Lakes to the Gulf” branch of the Lincoln Highway and “The Cotton Belt Route.” But what stuck was “Dixie Highway.”

Multiple explanations of the rise of the word “Dixie” exist, but many historians link the term to the Mason-Dixon line, the territorial border between Pennsylvania and Maryland that separated free-soil states from Confederate states. Its popularity is also attributed to the song “Dixie,” written by Daniel Decatur Emmett in 1859, which was widely regarded as the Confederate anthem. When construction on the highway began, it had been only 50 years since the end of the Civil War, and the Confederacy still festered in people’s minds. Promoters of this shiny new road wanted to paint a picture of a kinder South that beckoned.

By then, the Ford Motor Company had changed American transportation with its revolutionary Model T. Thousands of wealthy Americans flocked to Florida in their cars.

During the Florida land boom in 1925, some 7,000 people entered Florida each day, writes Christopher Knowlton in Bubble in the Sun: The Florida Boom of the 1920s and How It Brought on the Great Depression. They saw not the darkness of Jim Crow but their dreams shimmering in the swamps and surf of the Sunshine State.

Historians credit the Dixie Highway with building cities like Miami Beach, West Palm Beach and Hialeah, though it’s important to remember that by then, what’s known as the Great Migration, the exodus of six million Black people from Southern states to the North and West, had already begun. Between 1916 and 1920, 40,000 Black people left North Florida. A few of them migrated to South Florida, but most fled the South (on trains, which were much cheaper than cars) even as traffic going the other way got heavy on the Dixie Highway.

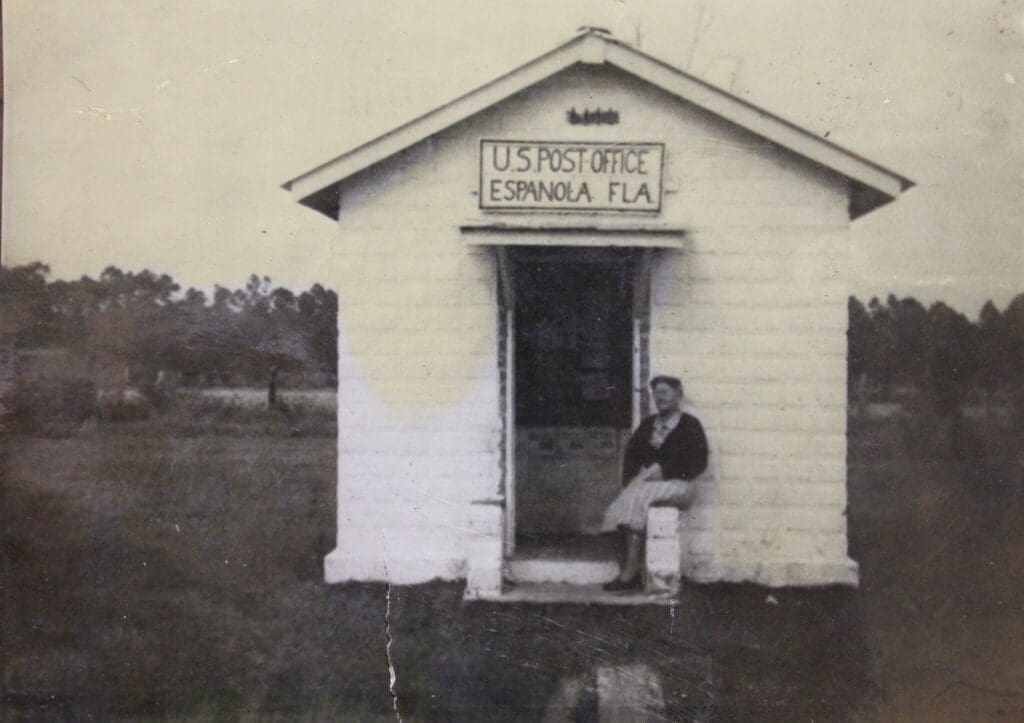

Little Espanola prospered. It had a hotel, a post office, a dry goods store, a grocery, a barber shop and camping grounds for vacationers. They were known as tin-can tourists—either because Model Ts were nicknamed “Tin Lizzies,” because of the metal campers they towed or maybe even for the tinned food they ate on their dayslong travels. Ryan, the historian, described the Espanola of the early 1920s as the Disney World of its time.

But as fast as the land boom came, it disappeared. The Roaring ’20s gave way to the Great Depression, and the new road to South Florida, U.S. 1, bypassed Espanola altogether.

“It used to be a real town,” said Ryan, the Flagler County historian. “But when they relocated U.S. 1, it kind of disappeared. Espanola isn’t there anymore.”

Except that it is. For people like Frank Giddens, Espanola has remained a constant. Around here, Blacks and whites still live in segregated communities and carry vastly different memories of the past.

The schoolhouse for Black children that Giddens helped build still sits a stone’s throw from the road that might have made this town something, that put this place on the map. Until the road was replaced and forgotten. As was Espanola.

I take in what’s left of the Dixie Highway, or at least the sliver that Randy Jaye’s Chrysler dares to traverse on this late summer day. It’s hard to imagine that this single-lane brick road served as a model for the maze of sophisticated highways and roads that would come to hold America together one day. I gaze toward the horizon that looms over the bricks from Birmingham. This was the road that helped make Florida what it is today, even though it died young and buried with it many a dream.

I sensed that the people who still call Espanola home prefer the road just the way it is: a relic, a part of the past that they believe is destined to stay that way. Nearby, the vast planned communities of Palm Coast threaten to gobble their way toward Espanola. Who knows if developers and politicians will one day find the Old Dixie Highway as abhorrent as its name? And then, perhaps, it will vanish altogether.