by Craig Pittman | October 18, 2021

Cattle Country: Keeping up with the Cowboys in Florida

Florida cattle ranchers hold fast to a 500-year-old American tradition that began in our state and is helping to save its remaining green spaces.

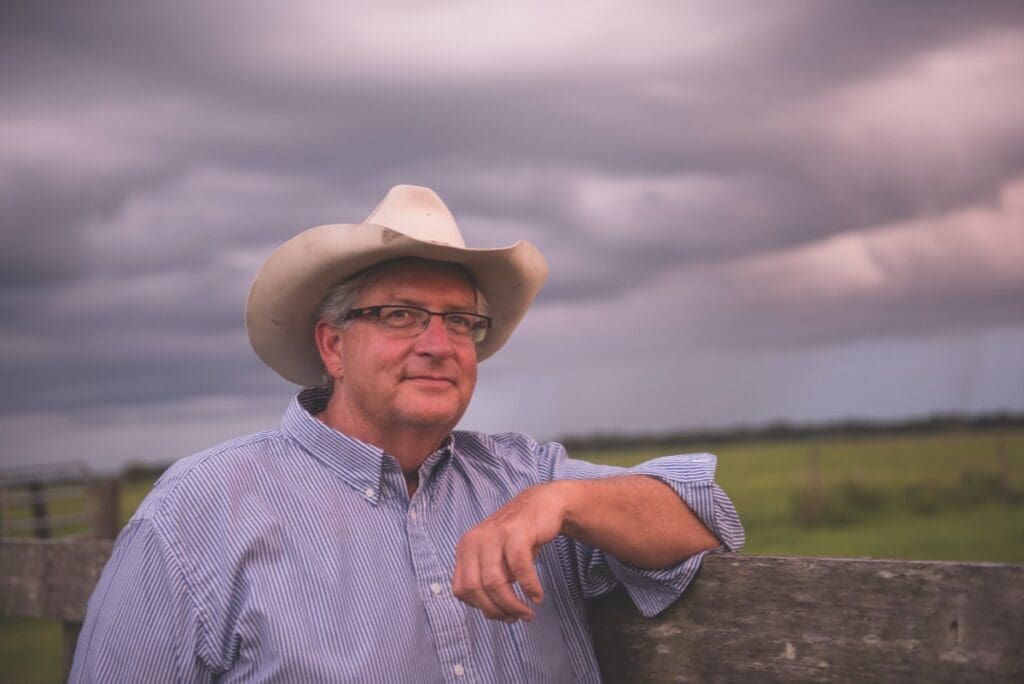

On a steamy August morning, as the temperature rose with the sun, Jim Strickland stood on a raised cypress board in a rugged cow pen at Blackbeard’s Ranch near Myakka City, looking down on a series of brown, black and reddish cows scooting through a cattle chute. They flickered by like images in a clattering movie projector.

Strickland, the ranch’s managing partner, wore a sweat-stained cowboy hat, a once-white fishing shirt with the sleeves rolled up, rumpled jeans and old gray sneakers spattered with mud. As the cows trotted past him, the 66-year-old rancher kept count. On every second or third one, he squirted a spray that would keep away flies for a week or so. When some of the cows hesitated, he’d slap them on the rump or the back lightly, urging them to keep going.

“Go on, baby,” he said to one.

The fly spray and the gentle touch are just two of the ways he and his ranch hands try to relieve stress on their cattle to ensure they don’t worry off some of their weight. Think of it as New Age cowboying.

Between squirts, Strickland reminisced about the good old days, back when he would load a Boeing 747 full of cattle and fly them to customers in Guyana, Pakistan and Dubai. Nobody overseas ever knew what to make of him.

“I’d get on an elevator somewhere and someone would look at my cowboy hat and say, ‘Are you from Texas?’” he recalled. “And I’d say, ‘Texas? What’s Texas? I’m from Florida, birthplace of the cattle industry in America!’”

Strickland was not exaggerating. In 1521, on Juan Ponce de León’s second trip to the land he’d named La Florida, the Spanish explorer brought along some Andalusian cattle, something never before seen in America.

I’d get on an elevator somewhere and someone would look at my cowboy hat and say, “Are you from Texas?” And I’d say, “What’s Texas? I’m from Florida, birthplace of the cattle industry in America!”

— Jim Strickland

When the Spaniard landed in Charlotte Harbor, his ship carried four heifers and a bull, along with 200 settlers. But Florida’s first conquistador didn’t stick around long enough to start a ranch. Calusa warriors attacked with a fusillade of arrows. One struck Ponce de León in the leg. It had apparently been dipped in the juice of the deadly manchineel tree. He died in Havana shortly afterward. The cattle, meanwhile, fled into the scrub.

From that inauspicious beginning grew an industry that did more than sustain the state’s economy throughout most of the 19th and 20th centuries. This year marks the 500th anniversary of cattle ranching in the United States. Historians say that ranching shaped the Florida we know today both geographically and culturally, boosting one-time cow towns like Arcadia, LaBelle and Kissimmee and cementing an attitude of independence and even a defiance of authority still around today.

Now ranchers like Strickland may be the ones who help save us from losing what’s left of the things that make Florida so special.

The First Vaquero

In movies and TV shows galore, the cowboy is an American icon—laconic, direct, a man of action. Think Marshal Matt Dillon and “The Lone Ranger,” Gary Cooper and “The Man with No Name.” In reality, the first cowboys were vaqueros who spoke Spanish and tended cattle outside St. Augustine after its founding in 1565. As the Spanish spread through North Florida, they brought their cattle, establishing ranches and training the local Native Americans to tend the herds too. Strickland can trace his ranching heritage back to just before the Civil War.

“I’m sixth- or seventh-generation,” he said. “Everybody in my family has loved the cattle business.”

The first of his ancestors to go into ranching relocated here from Georgia around 1850, he said. Cattle ran wild in the woods back then, and anyone who could catch a few could become a rancher. Florida was mostly open-range, without fences, until fence laws were created in 1949 because tourists started colliding with cattle on the roads. Plenty of white settlers had already moved here to take advantage of that open range.

“They knew all those cattle were here—it was one of the things that drew them to Florida,” explained James M. Denham, a history professor at Florida Southern College and the author of A Rogue’s Paradise: Crime and Punishment in Antebellum Florida, 1821–1861. “If you had cattle, you had status.”

During the Civil War, some of the sharper Florida ranchers sold their beef to buyers on both sides. Afterward, they found customers in Cuba willing to pay for their steers with sacks of gold. There are stories that some ranchers raked in so much money from the Cuban trade that they used full sacks of gold as doorstops.

Strickland says his family never enjoyed such luxury. What they valued was the cowboy lifestyle—riding horses and roping cattle, working outdoors and communing with nature—so they stuck with it.

“We’re barely making ends meet here,” he said. “I’ve always been blessed to do what I love to do. I have literally traveled the world with my cattle.”

Cowboy to the Core

In the old days, Florida ranchers trying to get their herds to market battled hurricanes, mosquitoes, bears, panthers, sinkholes and rustlers while driving thousands of cattle across the rugged landscape.

They were bound for ships docked in places like Tampa, Jacksonville and the long-gone community of Punta Rassa, near what’s now the Sanibel Causeway. They’d load the cows on sailing ships bound for other parts of the country or for Cuba, then celebrate with a trip to the nearest saloon or bordello.

These days, the life of Florida’s cowpokes is a tad easier. After Strickland and his helpers finished culling the herd, they loaded some of the cattle onto a double-level trailer to go to a buyer who’s a repeat customer. The truck and trailer belonged to a man named William “Bushrod” Duncan from Arcadia.

Duncan wore a cowboy hat like Strickland, and, like Strickland, he’s the son of a cowboy. In the 1980s his father, Jack Duncan, was still riding and roping at age 67, which earned him a write-up in the Los Angeles Times. The paper quoted Jack Duncan saying folksy things such as, “If you can’t do it on a horse, it’s probably not worth doing.”

“He was a cowboy ’til the day he died,” Duncan said, his mellow voice carrying a strong country twang. “He worked all day, came home and ate supper, laid down on the couch and passed away.” His father was 72 at the time of his fatal heart attack.

Them developers come in and offer you five times what it’s worth. And people who’ve worked hard all their lives, that’s hard to turn down.

—William “Bushrod” Duncan

Duncan, 66, started out chasing cattle through the woods with his father, but then injured himself during a rodeo.

“When I hurt my back, I just quit cowboying and took up driving a truck,” he said. “It was easier on my back. … I’m still a cowboy to the core. I just can’t ride [horses] like I used to.”

Duncan has watched with sadness the decline of Florida’s cattle industry as, one by one, the ranchers sell off their property. He understands why they do it.

“Them developers come in and offer you five times what it’s worth,” he said, “and people who’ve worked hard all their lives, that’s hard to turn down.”

Some ranchers do the developing themselves. Right now, the biggest land owner in the state is the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Church officials are already planning for the future development of some of their Deseret Ranch, situated near the headwaters of the St. Johns River. The scale of development proposed there, without significant conservation, could seriously degrade the water quality of the St. Johns River. According to Florida Trend, they envision 220,000 homes, 100 million square feet of commercial and institutional space and close to 25,000 hotel rooms where now there are cattle and wild palms.

Once ranchland is paved over, little remains to mark what was once there, although there are exceptions. When Al Boyd sold off thousands of acres of northern Pinellas County ranchland, the 17-foot concrete boot that marked the boundary of his Boot Ranch property remained. Now his land is covered in subdivisions and strip malls, and the big boot stands in the parking lot of The Shoppes of Boot Ranch.

Strickland’s story is more tragic than Duncan’s. His father was killed in an accidental shooting when Strickland was 17.

At the time, he said, “We owned a little land but leased a lot for cattle. I stayed a rancher because that’s what I loved but had a lot of help along the way. Mentors were and are a blessing.”

His father’s ranch foreman “took me under his wing and taught me how to rope and so forth,” he recalled. He and the other cowboys would ride horses to drive their herds from one part of the ranch to another part where they could feed. Then the cowboys would feed, too.

“The foreman would be driving a Jeep, and he’d meet us somewhere along the fence line and build a fire and cook us some lunch,” he said. “Some of us would hold the cattle while the rest of us ate lunch, and then we’d swap.”

Blackbeard’s current foreman can’t help with the cattle on this day because he’s in quarantine, recovering from a mild COVID-19 infection. Strickland runs the ranch with just two regular employees—the rest of the cowboys are day laborers, temporary hires who bounce from ranch to ranch.

As Strickland sorted the cattle on this hot day, the crew helping him included a 71-year-old neighbor spattered with mud from head to toe and the 11-year-old son of one of the ranch hands who’d wanted to accompany his dad to work. Both of them wore cowboy hats, but only the boy wore cowboy boots. The 71-year-old waded through the muck in white rubber boots that he called “Lakeport loafers.”

Both said they loved working with cattle, spending time outdoors and riding horses. Despite their age difference, they smiled a very similar smile.

Not present: Strickland’s son, who lives in Paris with his family and works for the diplomatic corps. Years ago, after spending lots of time ranching, he told Strickland, “I see how hard you work for how little money. It’s not for me.”

“Did it hurt my feelings?” Strickland said, looking down. “Yeah, a little.

Born to Ride

Like Strickland, Alex Johns grew up in the cattle business. Like Strickland’s son, he understands how low-paying of a profession it is.

“I’ve been involved in ranching from day one,” said Johns, 47. “I was born into it.”

He’s now the natural resource director for the Seminole Tribe, which means he oversees a co-op that controls ranches from the Georgia state line down to the Everglades. Yes, he’s heard the jokes about Indians playing cowboy, but points out that his tribal ancestors started tending the Spanish cattle five centuries ago, so they’re not newcomers to the field.

I stayed a rancher because that’s what I loved but had a lot of help along the way. Mentors were and are a blessing.

— Jim Strickland

Despite the romantic image of cowboys, “it’s pretty hard work, long days and very hot and humid conditions,” Johns said, “and they find out there’s not a lot of money.” As a result, he said, it’s “harder and harder to find good help.”

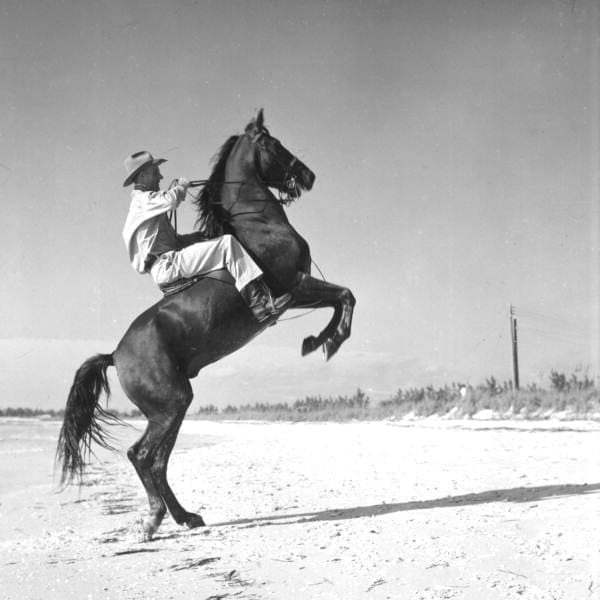

Back in the heyday of Florida ranching, from the 1870s to the 1930s, cowboys needed only a few tools to do their jobs: a reliable horse and a comfortable saddle, a rope for tying up the cattle, a leather whip for cracking over the herd’s head, a cow dog to help keep the cows going the right way and a good memory for brands. Plenty of them also carried guns and knives for fighting rustlers or rival cowhands from other ranches.

“People ambushed each other all the time,” said historian Canter Brown Jr., author of Florida’s Peace River Frontier. “It was a rough locale and a rough life.”

The premiere cowhand of those days was the tall and lanky Morgan Bonaparte “Bone” Mizell, who couldn’t write his own name but was renowned for his ability to recall every brand of every rancher in the region around Arcadia. (He was also renowned for his alcohol consumption. Once, after he passed out during a cattle drive, his compadres relocated his bedroll into a nearby cemetery. When he woke up and looked around, he said, “Judgment Day, and I’m the first one up.”)

These days, ranchers rely heavily on technology unavailable back in Bone Mizell’s day. The cattle have clips attached to their ears that can be scanned with a smartphone, providing a full history of each cow, Johns said. The Seminoles don’t drive their cattle to market. Instead, they sell them via internet auction, uploading a video of each cow. Spreadsheets track the history of the herd.

Strickland’s approach is similar. As the cattle he was sending to market took their turns on a cow-sized scale, the ranch manager frequently reached for his iPhone. He used it for calculations on their total weight before loading them on Duncan’s truck. He also sent texts and photos to his customers so they knew what they were getting.

After Duncan drove away, Strickland showed off the ranch to a visitor—not by straddling a horse but by firing up an electric golf cart. The cart bounced along through the pastures as the rancher pointed out wells equipped with pumps operated by solar and wind power and talked about analyzing soil samples to maximize the growth of grass for grazing.

Keeping the ranch gates open has required diversifying the products for sale, he said. In addition to selling prime cuts of its own beef to local restaurants, Blackbeard’s now sells Miakka Prairie Honey, collected from beehives set up across the fence from Myakka River State Park. Another product: eggs and meat from Blackbeard’s Heritage Breed Chickens. The ranch is developing a line of Blackbeard’s Miakka Goat Cheese, too.

The pandemic has made Strickland glad the ranch diversified. Last year, with so many restaurants shut down for months, he said, Blackbeard’s discovered that the only steady customer for its steaks was the fast-food chain Wendy’s.

Good Ol’ Days

As often happens with an industry on the downslope, some nostalgic people try to recreate the glories of the past.

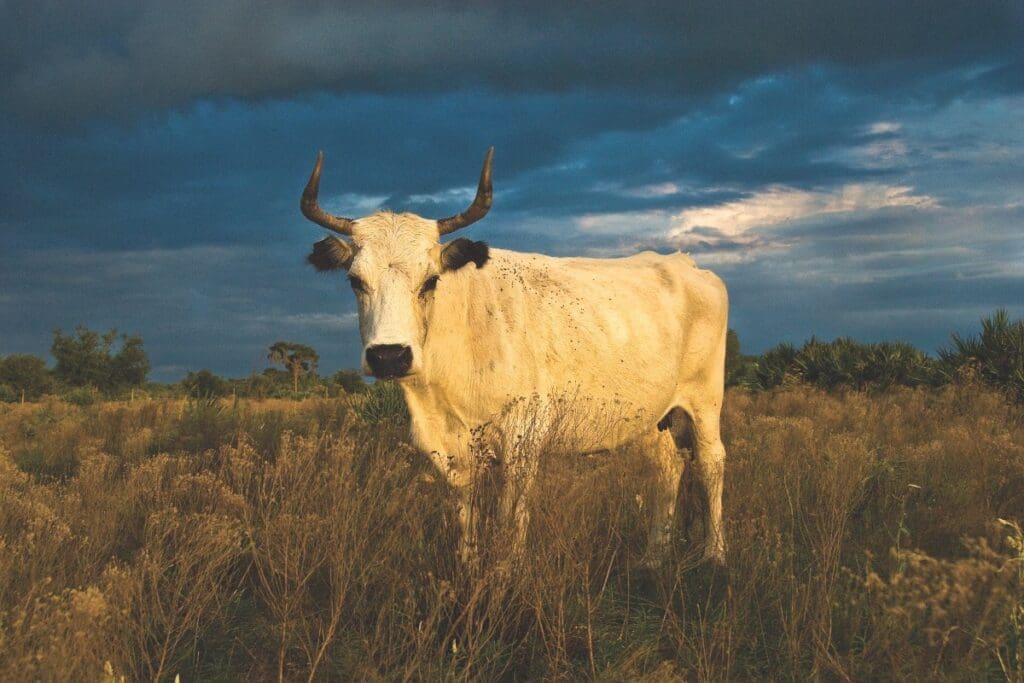

North Florida rancher and storyteller Doyle Conner Jr., for instance, said he got roped into leading the first Great Florida Cattle Drive in 1995. He asked ranchers throughout the state to lend to the drive a native Florida breed known as “cracker cattle,” instead of the more common modern breeds of Brahman, Brangus and Beefmaster.

The Seminoles and every county in the state sent representative cow hunters to drive a herd of 1,000 cattle from Yeehaw Junction to Kissimmee. In 2006, they repeated the event but reversed the route. The organizers wanted to hold one this year for the 500th anniversary of Ponce de León’s cattle arriving in Florida, but postponed it due to COVID-19. A few years ago, Strickland participated in what he said was “the world’s fastest cattle drive” to promote the launch of the photography book Florida Cowboys: Keepers of the Last Frontier by Carlton Ward Jr. and an accompanying art exhibit at the Tampa Bay History Center. Dogs that he and other ranchers brought along to lend the drive some historical authenticity got into a fight in the street. The snarling dogs stampeded the cattle so that they bolted past their destination and had to be brought back to the history center.

Strickland would much rather look forward to the future than back at the past. That’s why he likes Julie Morris so much.

Hallowed Habitat

Driving around the ranch, Strickland pointed out the different habitats—dry prairies, maiden cane marshes, live oak hammocks, cabbage islands and longleaf pine savannas. They all attract wildlife, some of it rare or endangered. That’s why he wants to maintain them just the way they are. For ranchers like Strickland who don’t want to see developers turn their land into a row of cookie-cutter homes, Morris has suggestions.

Morris, now with the National Wildlife Refuge Association, has been working to conserve ranchlands for decades to find ways to preserve native habitat on these properties and funnel some badly needed income their way.

Sometimes that means selling the development rights by giving the state or local government a so-called “conservation easement” on some or all of the property. Sometimes it means tapping some other state or federal program—or a combination of the two—to enable a rancher to continue the five-century tradition a few years more.

We’ve got to keep these ranchlands intact somehow. They’re keeping Florida green.

— Julie Morris

“When you look at these ranchlands from an ecological perspective, it’s such an eye-opener,” she said. That’s why the recently passed law creating the Florida Wildlife Corridor is so important for the future preservation of this type of land.

Anyone who wants to hang onto habitat for everything from gopher tortoises to panthers knows “we’ve got to keep these ranchlands intact somehow. They’re keeping Florida green.”

At Blackbeard’s Ranch, Strickland has made use of Morris’s recomendations to reduce the pressure to sell out the way some neighbors have. Beyond saving habitat, he sees a bigger reason to try to maintain ranchland as ranchland: climate change.

That’s why, he said, the future of Florida ranching and the future of Florida itself are intertwined. The future of ranches like Blackbeard’s may depend more on the ability to preserve the natural landscape—particularly carbon-absorbing forests—than on how many cattle can be sold at market.

Development has its place, he said, but “condos and new houses are not going to help you with climate change and sea level rise, not the way green space can.”