by Craig Pittman | July 19, 2021

A Tale of Two Toms and the Three K’s

How community historian Tom Garner unearthed the heinous truth about respected Pensacola figure T.T. Wentworth, revealing his role as a KKK leader, rewriting history and forcing positive change in the Panhandle town

When I was a teenager in Pensacola in the 1970s, I pursued the rank of Eagle in the Boy Scouts. One of my merit badge counselors was a tall, pale, white-haired man in his late 70s named Theodore Thomas “T.T.” Wentworth Jr.

He’s the only person I’ve ever met who ran his own museum.

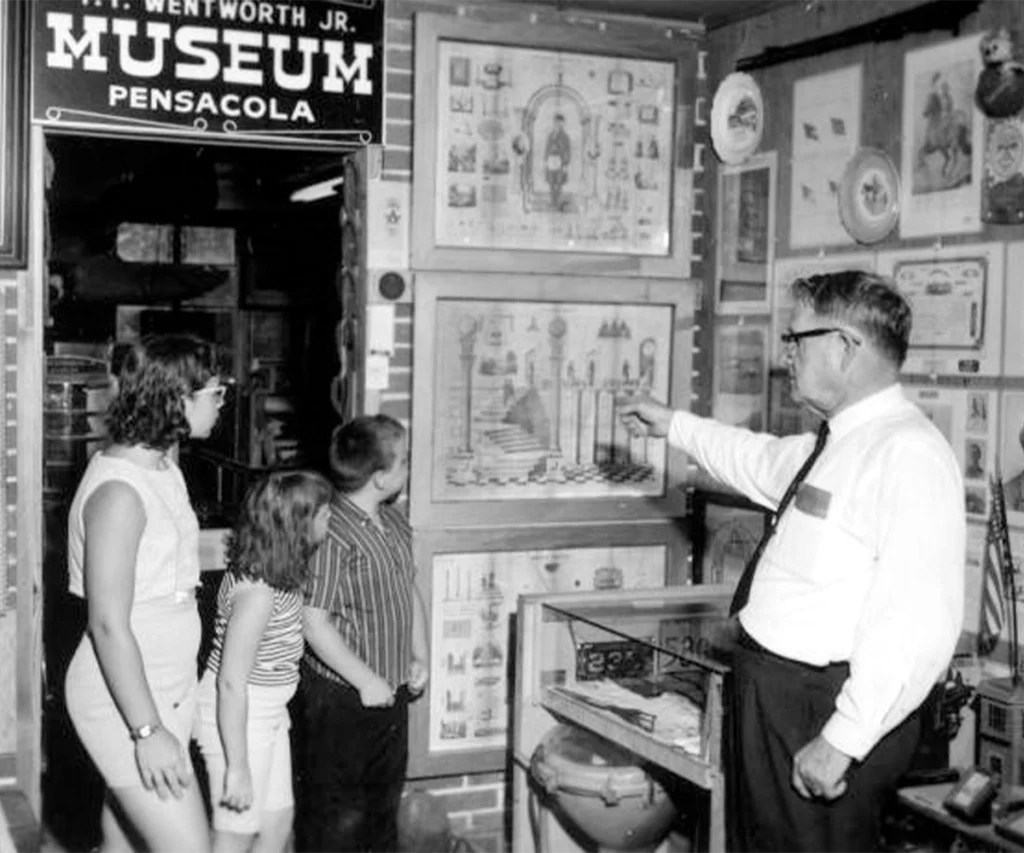

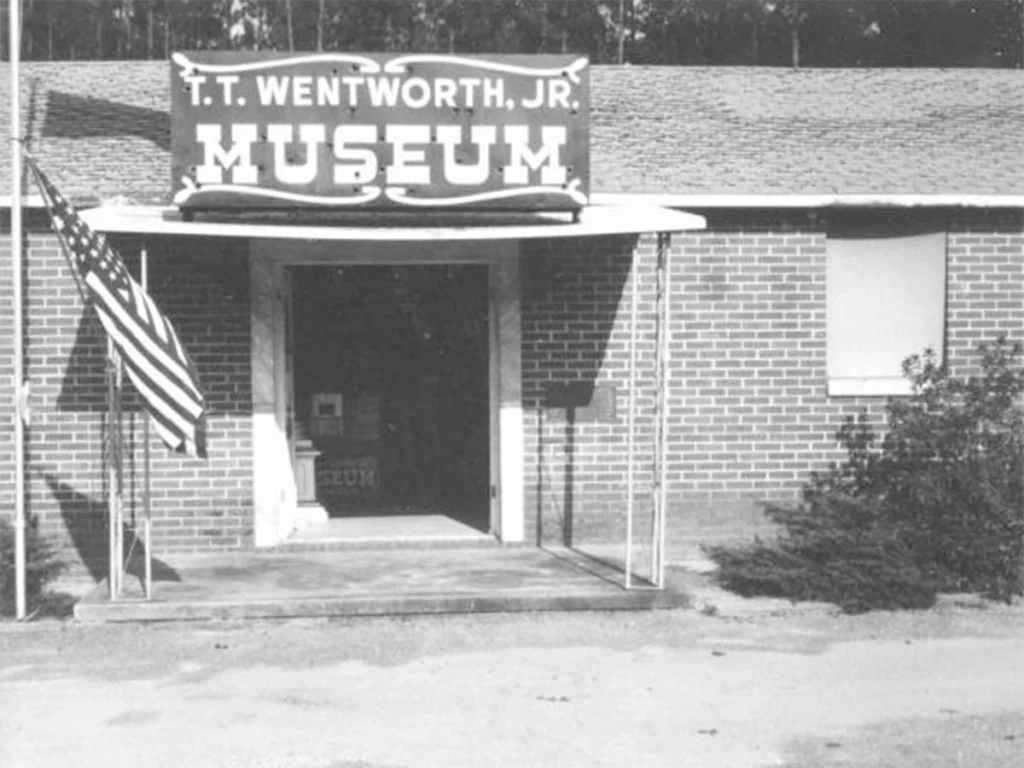

On Saturday afternoons, my mom dropped me off at old Mr. Wentworth’s roadside attraction, the T.T. Wentworth Jr. Museum, so we could check off merit badge requirements. At the time, “museum” struck me as a grandiose name for what looked like a dusty repository of oddball knickknacks.

He and I would start off going over the requirements I needed for, say, the Citizenship in the Community merit badge. But after 20 or 30 minutes, my counselor would bolt to his feet and announce, “Let me show you something!”

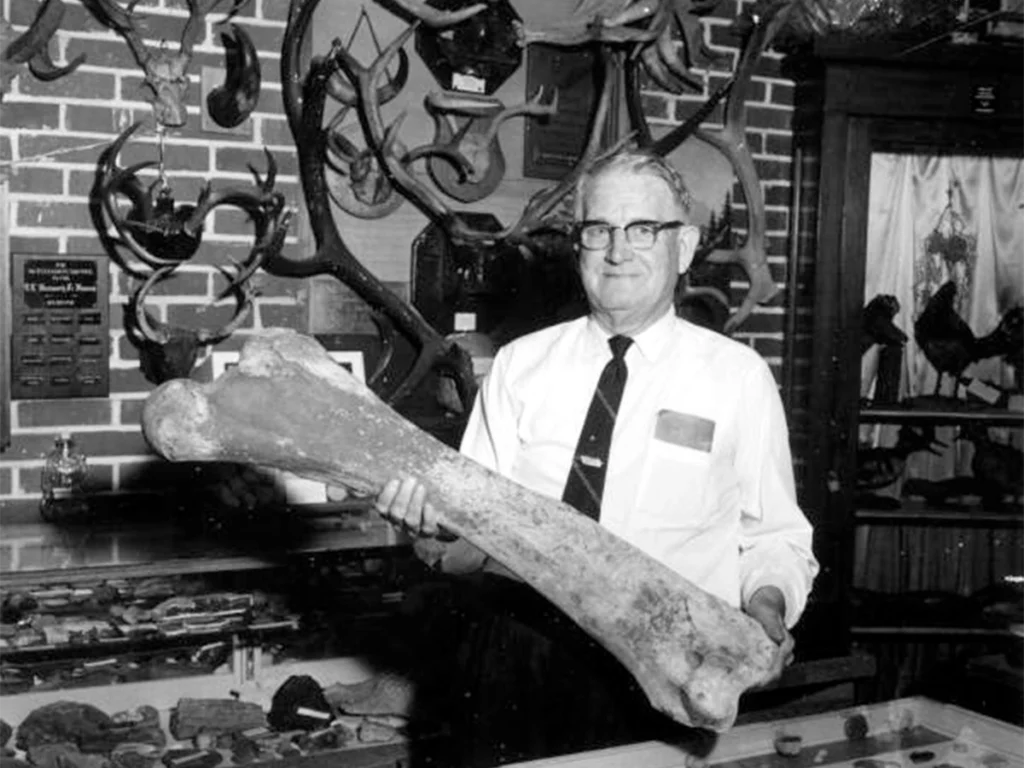

And off he’d go, dragging me along to look at some item from his collection, which began in 1906 when he stumbled upon a gold coin at the beach that turned out to date back to 1851.

He had a petrified cat! And bricks dating back centuries! And a wooden propeller from an old biplane! Do you like swords? He had a wall full of them! There were old newspapers in frames and license plates that hadn’t been valid for decades, and did I mention the petrified cat?

He must have shown me that darn cat 10 times, each time acting as if it were brand new. I got to where I hated that cat, but he never remembered that I’d already seen it.

I never made Eagle, but that was my fault for being lazy, not that of the easily distracted Mr. Wentworth. Back then he seemed like a nice guy if a tad eccentric. After I outgrew Boy Scouts, I hardly thought about him again until 1989, when my mom mailed me a clipping from the Pensacola News Journal.

“Historian and collector T.T. Wentworth, 90, dies,” proclaimed the banner headline atop the front page. The story, which included tributes from the governor and other notables, reported that among longtime Pensacolians, Wentworth was known as “Mr. Tom” and “Mr. History.”

In the 1920s, the story said, Wentworth had been elected a county commissioner—the youngest in the state—and then served as tax collector for 12 years. In the 1930s he helped to launch both the local library and the Pensacola Historical Society. He had led a public drive to save some of the area’s historic buildings, including Civil War-era Fort Pickens.

The obituary told me that in 1983, he had donated 250,000 items from his collection, valued at $5 million, to a historic preservation group that had opened a museum in the old Pensacola city hall—the largest historical collection ever donated by a private individual in the state, perhaps the nation, according to the paper. To salute his generosity, the museum took his name, calling itself the T.T. Wentworth Jr. Florida State Museum.

“I just hope it will always be like it is today, a big thing for Pensacola,” Wentworth said upon the occasion of his donation.

But that’s the thing about history. You think it’s all settled, but it’s not. Our perspective on it changes over time. New discoveries show old things in a new light. The status quo winds up being upended.

And so last year the old Mr. History was exposed as someone who was heinous and hateful, creating an uproar over whether the museum should change its name. The man who revealed his secret is Pensacola’s new Mr. History, who also happens to be named Tom.

Digging Up Dirt

Tom Garner is a genial, soft-spoken white guy in his late 50s, the son of a postal carrier. Like me, he grew up in Pensacola, amid an amalgam of influences and attitudes—a Southern Bible Belt city that’s also a port full of immigrants, a popular LGBTQ resort and a Navy base where swaggering pilots train for dangerous missions.

Garner graduated in 1980 from Escambia High School, where a 1976 riot over white students flying the Rebel flag led to National Guard troops taking over as hall monitors. Garner says he missed all that.

Health problems prompted Garner to drop out of college eventually, he told me. He never went back. These days he and his wife run a successful gardening business. But he’s better known around Pensacola for his other exploits in digging up dirt.

“I am not a professional historian,” Garner told me. “I am what I refer to as a ‘local historian.’ Every community has them. They are individuals who fall in love with local history and become very well-informed about it.”

His ability to burrow into historical records has benefited local environmental activists and journalists, according to Carl Wernicke, a former editor for the Pensacola News Journal. Wernicke, also a Pensacola native, befriended Garner while working with him to expose shady development schemes.

“He’s very brave,” Wernicke said. “He would have made a good reporter.”

I think what Tom did was put a face on the institution of the Klan—a well-known…face. He was the best person to tell it, and at the best time. —Robin Reshard

Garner’s interest in history started in the same way as Wentworth’s: with an accidental discovery in childhood. He was tossing around a football with friends as a middle-schooler when he spotted a bottle labeled “Hygeia.”

He took his find to Old Christ Church in downtown Pensacola. At the church, a man named Norman Simons ran a historical museum—small but with artifacts that were well-organized and professionally displayed, unlike the Wentworth collection.

Simons, who in his crewcut and tie always looked like he stepped out of a photo from 1958, explained to Garner that Hygeia was the name of a Pensacola bottling company. Just from looking at it, Simons could tell the bottling plant produced this bottle sometime between 1900 and 1910.

Garner was astonished. The bottle filled him with a thirst to learn more about the area’s history. Simons took him under his wing and taught him what he knew. Every time the Pensacola Historical Museum opened its doors, Garner would show up, pestering Simons with questions. Soon Simons was giving Garner small research assignments, teaching him to use microfilm to dig through old documents.

He introduced Garner to a professional archaeologist with the University of West Florida who trained him in archaeological fieldwork. Garner would go on to help start the Pensacola Archaeological Society.

I asked Garner if he’d ever met the other Tom or visited his original museum. He said yes, once, when he was in his teens.

“I went out there once on a Sunday afternoon,” he said. “I remember there was a little old man out there, and he shuffled around behind me as I walked around the place.”

Garner remembers seeing Wentworth’s bricks, but not much else, not even the petrified cat. Unlike the collection Simons curated, it “was just a real jumble of stuff, good things in with junk.”

After Wentworth donated his collection, Simons became the first curator of the T.T. Wentworth Jr. Florida State Museum.

Simons had one great passion: finding Pensacola’s original Spanish colony. Garner recalls “many conversations” about that mystery. When Simons died in 1989, the mystery remained unsolved—until Garner, the amateur, figured it out.

A Lost Colony, Found

Pensacola is the great also-ran of U.S. history. It was the first multi-year settlement in America to be established by European explorers. A Spanish explorer, Don Tristán de Luna y Arellano, landed there in 1559, six years before any Spaniards waded ashore in St. Augustine.

But five weeks after the Luna expedition landed, a terrible storm hit and smashed all the ships, which still carried the colonists’ food supply. The survivors struggled to avoid starvation and finally abandoned the colony. That’s why St. Augustine gets to brag that it’s the oldest continuously occupied city in America.

UWF archaeologists had found the shipwrecks but no sign of the Luna colony itself. Then, one October day in 2015, Garner went to Subway for lunch and on the drive back he passed through an older neighborhood near where the ships were found. Simons had told him this area matched the few written descriptions of the colony’s location, but no one had ever spotted any evidence.

On this particular day, Garner noticed one of the older houses had been torn down to be replaced by something newer. He stopped at what was now an empty lot and got out of his car, immediately spotting an olive jar neck and other artifacts on the ground—including some that to his practiced eye later appeared to be from the right time period for the Luna colony.

He notified UWF’s archaeologists, but they couldn’t jump on the find right away. Two weeks later, he collected a few pieces from the site and brought them in. One of UWF’s archaeologists sorted through everything slowly, then blurted out, “Holy moly!”

For discovering the long-lost Luna site, Garner was hailed as a hero. His discovery was written up in The New Yorker and other national publications. He landed a position with the UWF excavation crew, too, working as a liaison with the area homeowners to ensure access to the area. UWF included him in all its official press releases and documentation.

Six years later, though, he was out.

Erasing History

In 1861, Confederate soldiers plotted an attack on Pensacola’s Fort Pickens, but called it off because of bad weather. That’s how Fort Sumter became the place where the Civil War began. Otherwise, Pensacola saw little action during the Civil War.

Yet 30 years later, in 1891, a women’s group erected a 50-foot granite monument to the Confederacy in the middle of downtown—an obelisk so large it was as if the Battle of Gettysburg had been fought there.

The Pensacola monument was among the first of its kind to salute specific Confederate leaders. One side of the monument honored the nameless soldiers who died to save slavery. The other three sides commemorated their leaders: Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy; Stephen Mallory, secretary of the Confederate Navy who lived in Pensacola after the war; and Edward Aylesworth Perry, an obscure Confederate general from Pensacola.

The monument was Perry’s idea. As governor in the post-Reconstruction era, he pushed the poll tax and other tactics to squelch Black voting. Pensacola and other Florida cities had elected Black and Hispanic council members during Reconstruction. Perry revoked the charters of those cities so he could appoint all-white councils.

Perry died before the monument could be built, but his widow, a leader of the Ladies Memorial Association, carried out his wishes.

There it stood for more than a century, an ever-present reminder of the city’s racist past and one politician’s ego. Then, in 2020, as other cities across the South took down their treasonous statuary, the Pensacola City Council announced it too would consider removing its Confederate monument.

Garner wanted to contribute to the discussion. He’d been doing a lot of research on the history of racial violence in Pensacola. Some of the findings he delved into were horrifying, involving not just lynchings but rumors of mass murder. He’d also come across some interesting documents in the Wentworth collection.

People who objected to tearing down the monument claimed doing so would be erasing history, as if monuments were the only resource for learning about the past. Garner wanted to point out that the history Pensacolians embraced had already erased important facts because of who was telling the story.

Garner wrote a long letter to the City Council. He planted the bombshell in the 12th paragraph.

He began by saying the time was right to pull down the Pensacola monument. Then he went on to explain how the racism of leaders like Perry had, in that monument and other historical plaques and memorials, skewed or distorted the facts of Pensacola’s story.

After calling the roll of other inaccurate historical markers, he brought up the Wentworth Museum. He noted that Wentworth was remembered as a businessman, a county official and a devotee of local history. Then he hit the detonator.

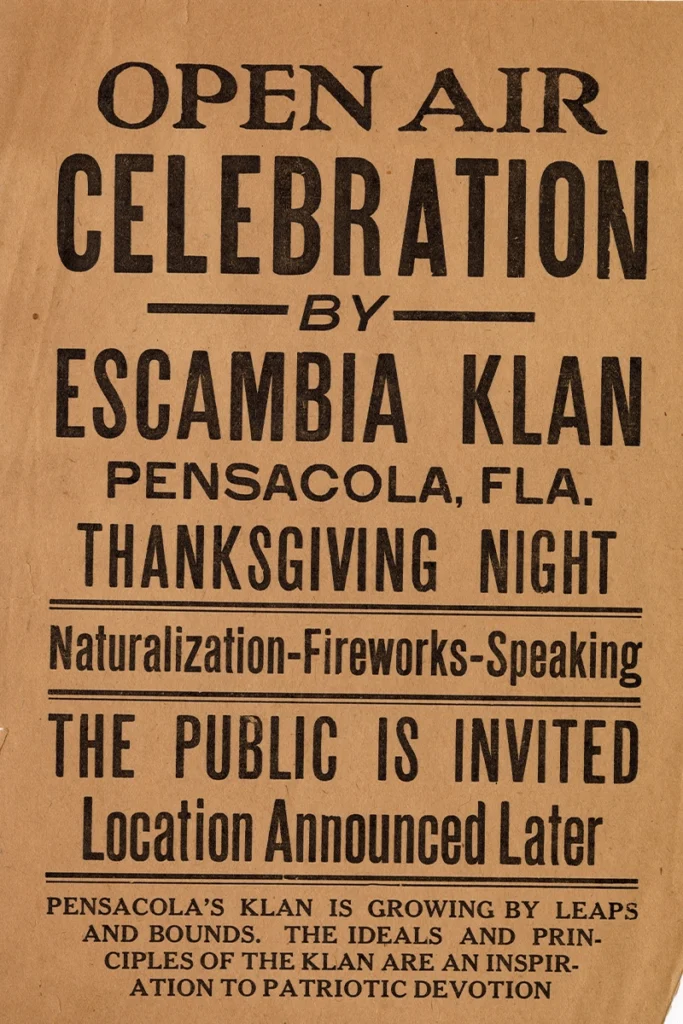

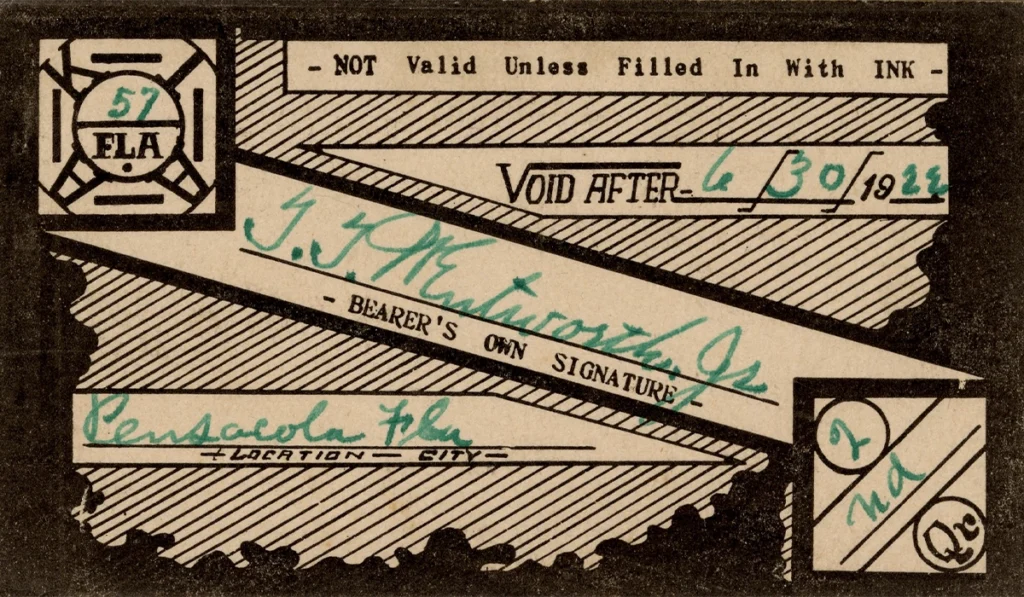

“T. T. Wentworth, Jr. was also Exalted Cyclops, Escambia Klan number 57, Invisible Empire, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan,” Garner wrote. “Documents record the founding of Escambia’s Klan in 1920, with Wentworth as its first Kligrapp, or secretary. In 1925, Wentworth was elected Exalted Cyclops, or president.”

“These documents, held in the museum archives, are from Wentworth’s personal files,” he continued. “Among the many Klan-related items in the files are Wentworth’s Klan membership cards, correspondence between Wentworth and the Grand Dragon, Realm of Florida, and an invoice for Wentworth’s specially ordered satin Exalted Cyclops robe.”

This, he pointed out, was the man who had controlled telling the Pensacola community’s history—a KKK leader. That’s why there was no room in the narrative for anyone who wasn’t white.

Garner’s letter didn’t just go to the council. His friend Wernicke arranged for it to be published in the Pensacola News Journal, along with the footnotes, ensuring it would have maximum impact on public opinion.

The letter sparked a front-page news story on July 13, 2020, headlined, “T.T. Wentworth was KKK leader in 1920s. Now UWF Historic Trust looks to change museum name.”

One person who cheered Garner’s discovery: Local Black historian and storyteller Robin Reshard, a friend of Garner’s.

“I think what Tom did was put a face on the institution of the Klan—a well-known…face,” she said. “He was the best person to tell it, and at the best time.”

Sure enough, the council voted to remove the Confederate monument. But Garner’s letter set a lot of other changes in motion.

A Klansman Revealed

Rob Overton, the executive director for the UWF Historic Trust, which runs the Wentworth Museum, was visiting family in Houston when the Klan news hit.

As soon as he heard about Wentworth being a Klan leader, “I headed home and started working on a press statement.” His initial reaction, he said, was, “The sky is falling.”

His other reaction: “I wish Tom had come and told me about it.”

Neither Overton nor anyone else in the museum’s management knew the extent of the Klan documents that Garner had found in their archive.

They were not part of the original collection Wentworth had donated to the state. Wentworth had kept those in his house, where members of his family lived for years after he died. Once those relatives were gone, the bank serving as the estate’s executor invited the museum staff to look through the house for additional exhibits.

“It was two floors and an attic, and there was stuff everywhere,” Overton told me. The power was mostly off, so no air conditioning or lights. “We’d go out there with flashlights and boxes one day a week, starting in 2016. We got the last of the boxes in 2019.”

They put all the boxes into freezers to kill any bug infestation and await the deed of gift from the family, he said. Only then could the museum staff and volunteers begin cataloguing the contents.

Garner just happened to be in the museum doing research when UWF’s longtime archivist, Jacqui Wilson, noticed a box of documents that seemed to have something to do with the Klan. She didn’t have time to go through it then, but she knew someone who did.

“It was just the two of us there in an empty office, and she sets it on the table and says, ‘Knock yourself out,’” Garner recalled. “I opened up the box and my jaw fell on the floor.”

The documents unveiled more than just Wentworth’s scandalous past. They offered “an unprecedented window onto the workings of a Florida Klavern during the 1920s,” according to a report released in July by a group of historians and others connected to the museum,

Wentworth’s files showed how the secretive group operated and how deeply it reached into government. Members included state legislators, the superintendent of education, a judge, even the city harbormaster. People wrote to Wentworth asking for the Klan to intervene in their personal troubles, such as punishing a spouse for cheating. Because he was the local Klan leader, the police chief gave Wentworth a card granting him police powers within city limits.

In 1927, Wentworth sent a letter to a Klan leader in Atlanta in which he gave a summary of his Klavern’s activities. It became the first history written by Mr. History.

He complained about how some people in Pensacola—Catholics and foreign-born residents—persecuted the local Klansmen via business boycotts. Bank officials refused to give a Klan-connected businessman a loan. Wentworth included dramatic stories of an attempt by the Knights of Columbus at stabbing a Klansman “with a keen-edged pocketknife” and a mob attack on an unnamed Klan leader in the city’s court, with their target driving them back “with a thirty-eight nickel-plated revolver.”

Wentworth didn’t hide his membership. When the Klan ran ads in the local paper, the bills went to him. Between 1923 and 1925, Wentworth published pro-Klan articles in his Tom Wentworth’s Magazine, touting “true Americanism and Protestantism.”

“This is really his voice,” said Jamin Wells, the University of West Florida professor who has spent the past year digging through all the Wentworth documents. The Klansman he described facing a business boycott and threats of violence was clearly Wentworth himself, Wells said.

When Wentworth joined the Klan in the 1920s, the organization had distanced itself from the bloody violence of its early years—or so it seemed.

“It was seen as respectable, from the white side,” said Michael Butler, a Flagler College history professor and the author of Beyond Integration, a history of the Panhandle’s civil rights struggles. Members were “professors and civic leaders, ministers and bankers. Belonging was a mark of patriotism. It was the 1920s equivalent of joining the Lion’s Club, if the Lion’s Club was an expressly racist organization.”

But what most Klansmen did not know when they joined is that “it was essentially a Ponzi scheme,” Wells explained.

Once someone like Wentworth joined, the organization started hitting him up for money. He had to pay his dues. He had to pay for his robe. He had to round up other people who would join and pay those fees as well, Wells explained.

The documents and contemporary news accounts show the Klan had never really stopped being a violent organization. Wentworth’s Klavern ordered a Greek restaurateur to leave town or else. There are hints in Wentworth’s correspondence that he and his colleagues burned down a Black-owned hospital.

Around 1930, Wentworth had apparently lost interest in the Klan. He got a letter from the state chair reminding him his dues were unpaid. The files contain nothing to show Wentworth replied.

But he didn’t come clean about it, either. Fifty years after he let his Klan membership lapse, “when offered the opportunity to discuss this history…Wentworth claimed no direct knowledge of the Pensacola Klan and provided inaccurate information to a reporter,” the historians’ report said.

The report notes: “With a few notable exceptions, Wentworth did not collect material related to African American history nor did he meaningfully include the African American experience in his histories of Pensacola.”

“Retired” or Fired?

When Garner saw what was in the box the UWF archivist had handed him, he pulled out his cell phone and took pictures of the documents, then put them back. He didn’t tell her about the pictures, either.

He says he didn’t tell the archivist about what he was doing “because I wanted her to have deniability” should there be a backlash for exposing the secret life of Mr. History.

If I had found what Garner discovered, I would have shouted it from the rooftops. But Garner sat on the information for nearly six months.

He didn’t mention it to university officials, his fellow historians or anyone else. He said he planned to offer to help the archivist catalogue everything, but two months after he found the Klan documents, the pandemic forced the closure of the archives.

“I had no plans to share the photos with anyone, particularly not the media,” he told me. Only the Confederate monument debate prompted him to reveal it.

After Garner’s letter ran in the newspaper, along with his photos of the documents, the archivist who showed the papers to Garner abruptly retired.

I asked Overton if she’d been pushed out for showing Garner the Wentworth documents before anyone else had seen them.

“That’s a personnel matter and I can’t get into that,” Overton told me, then added, “We have policies in place, and we have to abide by those policies.”

A representative of the Florida Archivists Association said she’d apparently been pushed out for doing her job. I contacted the archivist to ask her about her retirement. She said she’d have to think about commenting, then hung up. I didn’t hear from her again.

The life of T.T. Wentworth seemed to have a great big old ‘oh shoot’ and that’s his membership and leadership in the Pensacola Ku Klux Klan. I ask you, are there enough ‘attaboys’ to make up for that one big old ‘oh shoot’? —Robert Jones

Then, when I asked the university for pictures of Garner, a public relations person said he was no longer an employee there. That was news to Garner.

The loss of the position didn’t hurt him financially. His gardening business took off during the pandemic. But the loss of a job connected to the archaeology site he found left him feeling sad and hurt.

“Working at the Luna site, being part of the Luna project, was never about the job,” he told me in a long text. “It was something I loved and that I believed in. I still do.”

Oh Shoot!

Sharon Yancey has the unenviable job of speaking on behalf of Wentworth’s descendants. Her connection to the man is not direct—her aunt married Wentworth’s oldest son but died three years ago.

She has some personal memories of him, though. She remembers how he’d show up for a family dinner and be “holding court, waxing eloquent and ready to eat.” She recalls how “he’d walk into a room and people would see him and say, ‘Oh, it’s T.T, let’s gather over there and listen to him…He always had a story to tell.’”

She grew up hearing about how generous he was, how many people he helped over the years. Garner’s revelation of his racist past rocked the whole family, her included. However, the one thing that did not surprise her was that the revelation came from things he’d saved—things someone else might have destroyed or thrown out.

“That man never threw anything away,” she told me. “Was he a hoarder? Probably.”

As the founder of a Christian ministry for children, though, she cannot defend what he did. It’s “antithetical to everything I stand for,” she explained.

She served on the board that advised Wells about his report for UWF, as did Garner, who found her quite impressive. She is now working to create some sort of healing event for the community, she told me.

The family is “very sad” about Wentworth’s past, she said, but they would not oppose an effort to take Wentworth’s name off the museum. Their namesake gave away all rights to his collection, she said, so the family feels like it’s none of their business.

But there are white people in Pensacola who think otherwise. When Overton’s organization brought up the idea of taking Wentworth’s name off the museum, some decried it as the worst kind of cancel culture. Others contended that misdeeds from such a far-distant past should have no effect on the present and that the Christian thing to do would be to forgive him for a youthful indiscretion. A year later, the controversy continues to rage on social media.

“I knew T. T. Wentworth… This man that I knew for over 60 years was not a racist,” a former public official convicted of bribery wrote recently on a Facebook page for people from Pensacola. “Mr. Wentworth was a good man, and the University of West Florida and the Press distorted a good man.”

Nevertheless, UWF Historic Trust’s board voted unanimously to take Wentworth’s name off the building, although not off the collection he donated. The Florida Historical Commission followed suit in February. But the university’s own trustees were not as ready to cut ties with a blatant racist.

One trustee, economic consultant Robert Jones, who is white, argued that Wentworth’s other good works might outweigh his Klan support.

“My dad who was a historian his whole life … once said to me, ‘Robert, it takes an awful lot of ‘attaboys’ to overcome an ‘oh shoot,'” Jones told the other trustees. “The life of T.T. Wentworth seemed to have a great big old ‘oh shoot’ and that’s his membership and leadership in the Pensacola Ku Klux Klan. I ask you, are there enough ‘attaboys’ to make up for that one big old ‘oh shoot’?”

After a long debate, trustees voted 5-4 to approve the name change. Media reports at the time said the next and final step would be the approval of Gov. Ron DeSantis and the Cabinet, but in April officials with the Division of State Lands decided that wasn’t necessary. At the end of June, the Wentworth sign came down, to be replaced by one proclaiming the building to be “the Pensacola Museum of History at the University of West Florida.”

In July, UWF posted digital images of all of Wentworth’s Klan files so the public can see what they say. Anyone who reads them will see there’s no ambiguity about the connection between “Mr. History” and the racist organization. It’s just as real and ugly—and far more disturbing—than that petrified cat.