by Eric Barton | December 21, 2020

The Black Football Players Who Changed the Game Forever

A single touchdown began the integration of football in the Old South

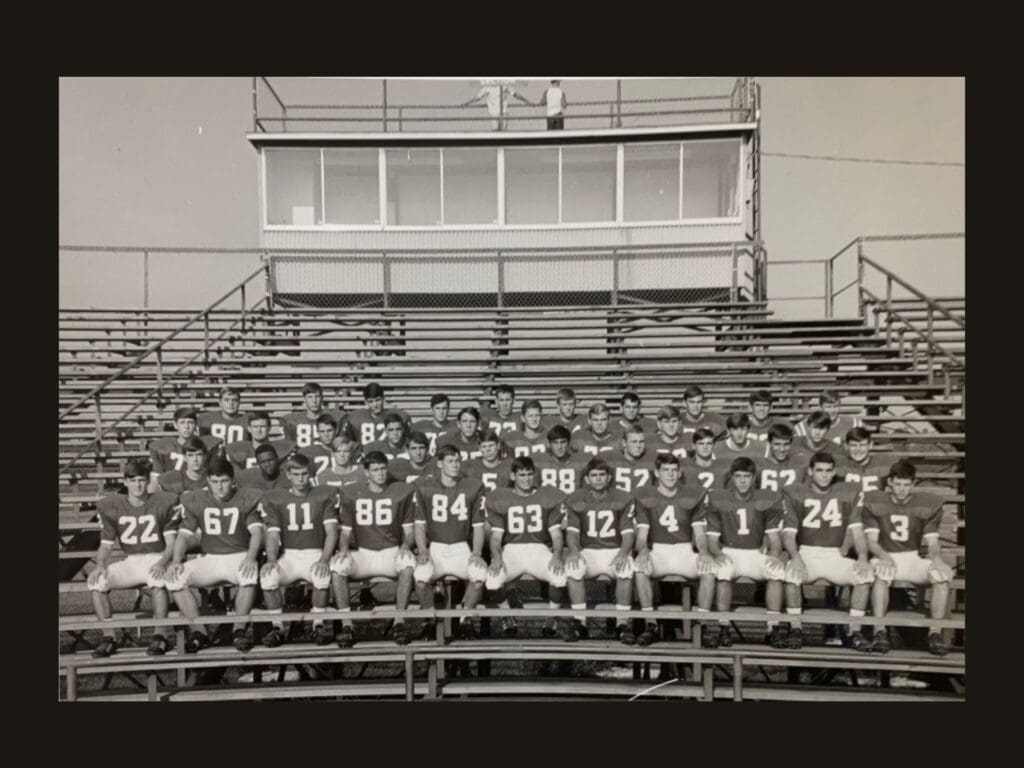

The 1970 team photo for the University of Alabama’s football team includes four lines of young men, the first line sitting, the next kneeling, and then the others standing, arranged by height—big boys in the back. All of them, every single one, is white.

They’re doing their best to look brutish and intimidating, but they’re baby-faced, really just big children. Of course there’s no knowing today if each of those boys was a racist. But these were the sons of a generation represented by the brutality on the Edmund Pettus Bridge down the road in Selma. Their fathers were part of a system that forced seamstress Rosa Parks to the back of the bus in Montgomery. Their coaches refused to allow Black players in their locker room.

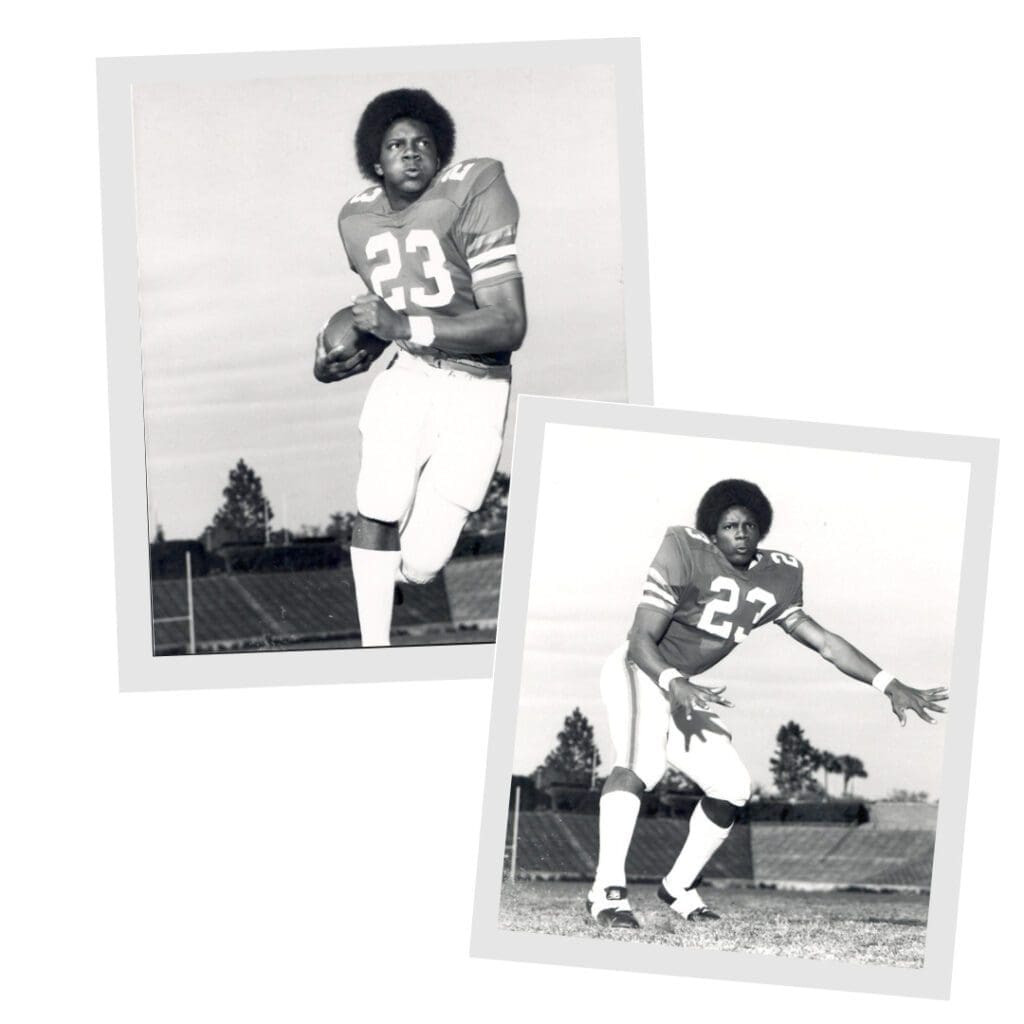

So just imagine what it was like for Leonard George to line up across from those boys on Sept. 26, 1970. That was his first year playing varsity for the University of Florida Gators, and getting put in the game, in Tuscaloosa, was everything to him. The fact that he was black, he says now, didn’t cross his mind. At least right then, he wasn’t pondering the significance of what it would mean if he were to score, to be the first black man to bust through that line of white faces into Alabama’s home end zone. In a shameful section of America that had largely refused integration, Leonard George could challenge a literal and actual color line.

“I wasn’t thinking about what it would mean,” George says today. “I was saying, ‘Wow, I’m in the game, and we’re close to the goal!’ I was really just excited to be out there.”

With the ball lined up between the 1-yard line and the end zone, the Gators were just inches away from scoring. With the snap, the quarterback stuffed the ball between George’s hands. He pushed forward.

Most likely you don’t know Leonard George’s name. But with that play, he became the first black athlete to score a touchdown in Tuscaloosa against the juggernaut that was the University of Alabama football team.

After that, universities across the Old South that had refused to integrate football teams gave in and offered scholarships to black kids. It wasn’t that they realized the error in their prejudice: it was simply that George’s touchdown showed that they’d be more likely to win with black players on their teams.

George and other black players who forged their way onto Southern football squads withstood awfulness that’s hard to comprehend today—the screams of bigots, the beatings, the soul-crushing swallowing of hate even from their own teammates. They were the Jackie Robinsons of college football, and they’ve gotten very little recognition for it.

GAME CHANGERS

The integration of football in the Old South did not start with a pioneering university president or coach. There would be no Branch Rickey, the Brooklyn Dodgers owner who hired Jackie Robinson. There would be instead a tiny Tampa high school called Jesuit.

In 1964, Jesuit became among the first Florida high schools to integrate. For a private Catholic high school, the decision to integrate wasn’t all that groundbreaking at first. The innovation came when the football team went on the road.

Jesuit’s schedule was stacked with many of the state’s powerhouse schools, many of them located in the center of the peninsula, decidedly Southern, undeniably segregated. Drew Marquardt, a filmmaker, is currently in postproduction on a documentary about Jesuit’s first integrated football team. They heard all kinds of insults from the fans in Lakeland and DeFuniak Springs, Marquardt says, but nothing was worse than the audience in Lake City.

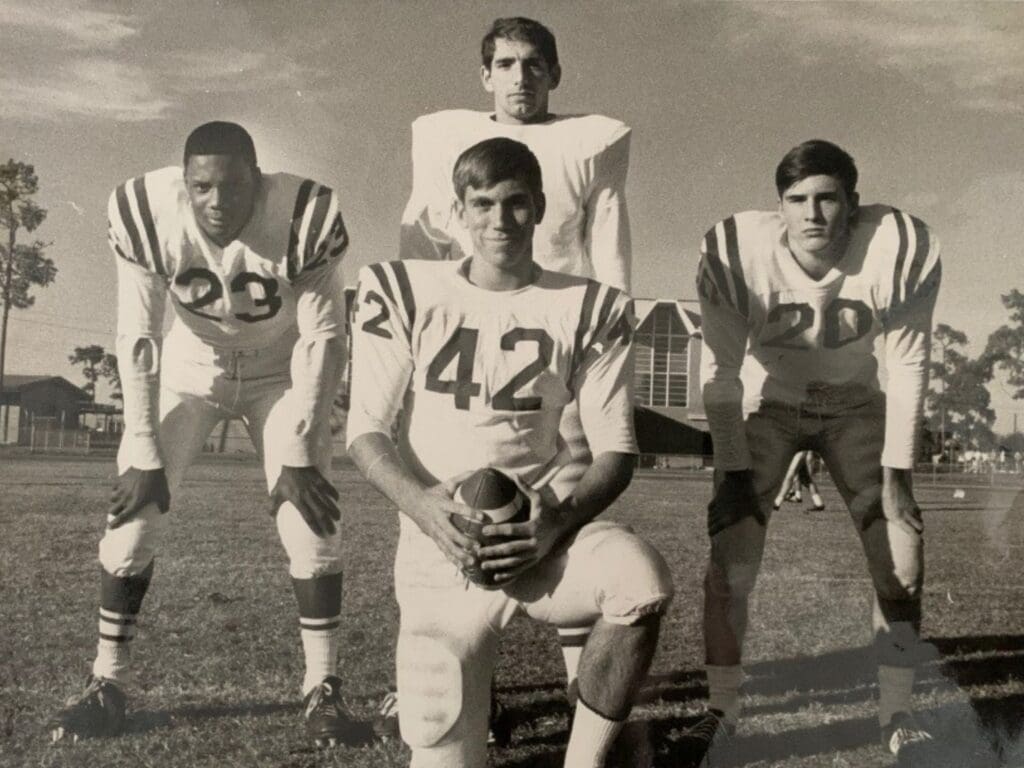

That game against Lake City was part of the semifinals for the 1967 state championship, and the star player for Jesuit was Leonard George. Knowing they needed to stop George, Lake City sent in a a lineman low on the roster but known for his size. After one play, he started throwing haymakers at George. “They sent in this third-string guy, basically like a hockey bruiser,” Marquardt says.

George, now 69, still remembers the feeling of those fists coming down on him. “Man, he’s just pounding away on me. I said, ‘At least I have to defend myself.’ And they said, ‘You’re both out of the game.’ And I said, ‘God, what is this?’”

They sent in this third-string guy, basically like a hockey bruiser.

—Drew Marquardt

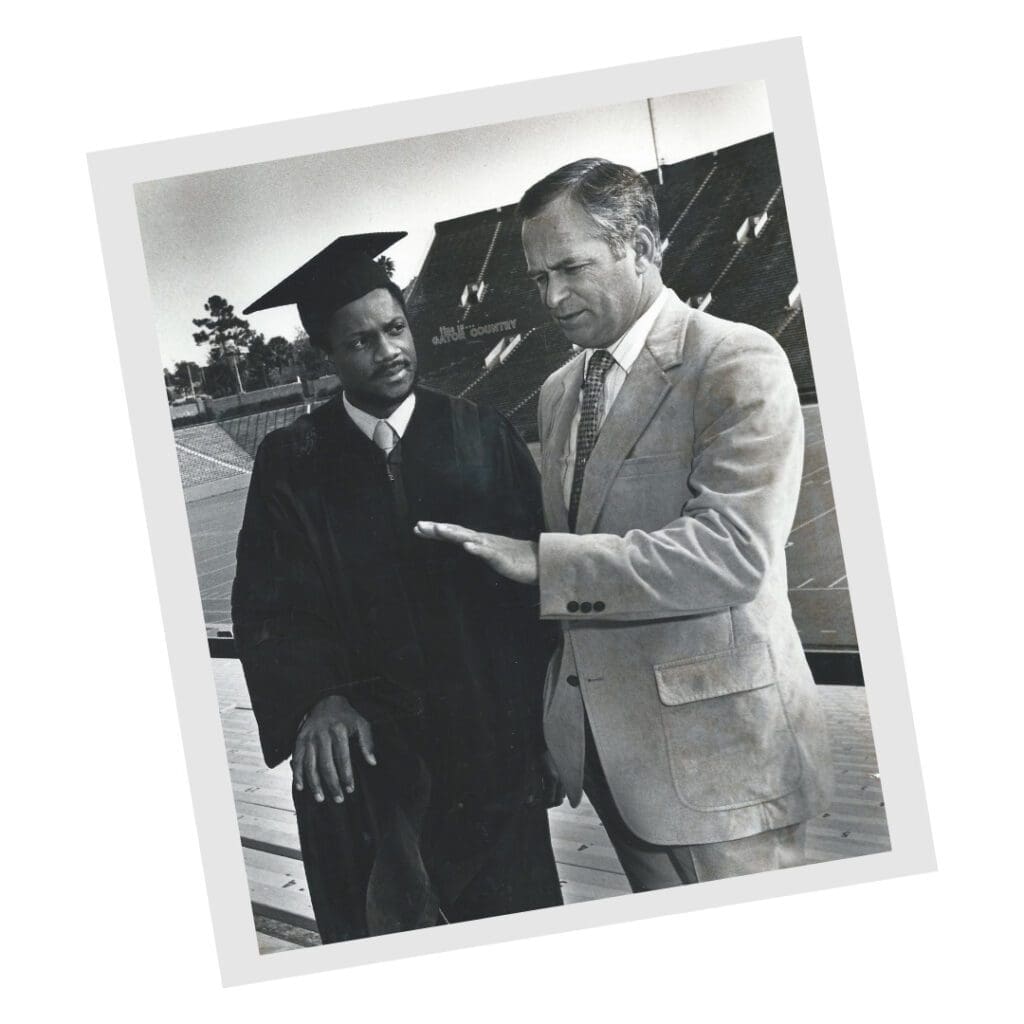

In 1968, George became the first black football player to receive a scholarship from the University of Florida. He would be joined by another: wide receiver Willie Jackson. When George started playing for the Gators’ varsity team in 1970, that moment in Lake City would define how he’d carry himself, how he’d react to the hatred, to the things they yelled at him as he walked on the field with his teammates in Mississippi and Alabama and Georgia.

It was like that for every one of those pioneering black athletes in Florida. Many of them met tragedy and hardship, and few look back on those victories without remembering the pain of the verbal and physical assaults rained down on them.

Calvin Patterson, Florida State’s first black football player, had also been among the first to break the color line at Miami’s Palmetto High. When he accepted a scholarship to play at FSU in 1968, he got death threats not only from opponents but also from fans of his own team. His grades tanked, and he lost eligibility to play, never getting in a game. At just 22, Patterson shot himself.

At the University of Miami, Ray Bellamy became the first black student athlete in 1967, a year before George joined the Gators. Bellamy was a star in football, basketball and track, but he still never felt welcome on the football field.

All these years later, Bellamy says today he tries not to think about those days. “I had this thing in me, whatever I did, I would take it to my grave,” he says. “There are some things you live through, and you don’t want to live through them again.”

Not that long ago, Bellamy heard one of his former white teammates at UM was doing poorly, with likely just days left to live. So Bellamy gave him a call, after not seeing him for a lifetime.

“I stood in the huddle next to him for many games, and I called him up to say as a teammate I cared about him. He said, and he’s on his deathbed, he said, ‘Listen, Ray, I don’t deal with people like you. Don’t get me wrong, Ray. I have nothing against you. But I don’t deal with your people.’ Can you imagine that? That really hurt me. That really hurt me a lot.”

Most likely, Bellamy would’ve gone on to play pro football if not for a car accident that nearly killed him in 1970. He stayed at UM and became the first black student class president. He earned three degrees, including a master’s in college student personnel. He got married, had four children and works as an administrator at Florida A&M in Tallahassee. Unlike some black players of his era, who want to relive the games or the hardships, Bellamy says he puts the vitriol of the past out of his thoughts.

“I have a clean heart, and it’s behind me now.”

It’s not like that for Leonard George, who looks back on that game in Tuscaloosa with what sounds like sheer joy, like he’s still that sophomore handed the ball at the goal line.

AN UNEXPECTED HOMECOMING

That touchdown by Leonard George wouldn’t have been possible without Carlos Alvarez, and still today, Alvarez likes to joke that he deserves a footnote to history.

Alvarez was a wide receiver for the Gators, a Cuban immigrant with light skin who says he didn’t face the same prejudices. He had only that one moment—when he was a sophomore, in 1969, and had caught a pass against Mississippi State that the ref called out of bounds. Alvarez got up and started arguing with the ref, when a Mississippi state trooper standing on the sidelines interrupted: “Mr. Alvarez, that may have been in in Havana, Cuba, but it was out in Starkville, Mississippi.”

In 1970 Tuscaloosa, Alvarez remembers feeling like the whole stadium, all 58,000 people, were cheering against Leonard George as much as they were cheering for the home team.

In the play just before George’s historic touchdown, Alvarez found himself open in the end zone. The Gators were running a quick slant, but the Alabama player assigned to cover Alvarez thought it was an out pattern. Alvarez was wide open, a pass spinning toward him, the end zone below his feet. The defensive back knew it was a touchdown.

“He just draped himself all over me, because there was no question it was going to be a touchdown.”

The refs called it pass interference, giving the Gators the ball on the half-yard line. George came in the game, and they called a simple play: George was to run up the middle, between the tackles, and dive.

It wasn’t a simple thing. Not only did George have to contend with that line of white faces on the Alabama side, but it was like the sky above was against him. It was unseasonably hot for late September, nearly 90 degrees. The university had installed a new field of Astroturf, and the concrete below it had radiated heat all day. Worse, the visiting locker rooms in Tuscaloosa had no AC. Gators players would stick their feet in ice baths between plays.

There was also that feeling that somebody in the crowd or on the other team just might do something about Leonard George.

It was the Old South. A lot of Confederate flags and angry people in the stadium. I felt like the only black person in the whole stadium at that time.

— Leonard George

“It was the Old South,” George says. “A lot of Confederate flags and angry people in the stadium. I felt like the only black person in the whole stadium at that time.”

But no matter what the fans said to him, no matter how he felt looking up and seeing those Confederate flags everywhere, he always thought back to Lake City. It’s what he’d done his first time seeing the flags flying in Mississippi, where he knew he had to avoid a conflict.

“When you’re the only black player on the field in Mississippi, are you going to get in a fight? Are you going to yell? Because then you’ll get the whole stadium down on you, and I’m sure they would’ve loved that,” he said.

He learned in Lake City that even if he simply defended himself, even if he raised a fist only to keep himself from being beaten, he knew how the crowd and the refs would see it: he had been the aggressor. At the least, they’d throw him out of the game, as they had when he was a high school junior. And so he internalized the cruel treatment, in a way that’s incomprehensible for those of us who have never had to endure it.

You might be surprised at the way he laughs about the 1970 game now, about what he went through to be there. He’s an optimist, choosing to focus on the good moments—the touchdown, rather than whatever it took to get there. Ask him about where he stayed in Tuscaloosa, and he’ll say, “I don’t know if they had to make special arrangements because of me or things like that.”

When he scored and found himself in the Crimson Tide end zone, George didn’t think about what it meant. He didn’t look up at the faces in the crowd to see a collective look of disdain or disappointment or realization of an error in ways. He was, after all, just a kid with a ball.

“What a joy that was! But it took years and years to think about, I mean, at the time I wasn’t thinking about all those things, to score a touchdown against Alabama, in Alabama, in Tuscaloosa. All I was thinking about was helping my team and scoring a touchdown.”

After graduating, George returned to the University of Florida in 1978 to become among the law school’s first black students. It wasn’t nearly as hard because “I didn’t have to go through Alabama and Mississippi.”

He was assistant attorney general in Tallahassee after graduating from law school in 1980, then moved to Atlanta and had his own law practice there for 13 years. After a short stint living in Tampa, George moved to Hawaii in 1999, where he became a mediator, and lost touch with his former teammates. Many of them thought he must have died, and he had become something of a folk hero, this pioneering black athlete who just disappeared.

Over the years, the distance took a toll, and George wanted to “come back to all the things and the people I know, including Jesuit and the University of Florida.”

He moved back to Florida in 2019, and that year he showed up to homecoming. At halftime, the Gators recognized the 50th anniversary of that historic 1969 team. Alvarez—who also went on to become a lawyer and mediator, still practicing in Tallahassee—says it should be just the start of the recognition George and Jackson deserve.

“Leonard George and Willie Jackson always, always rose above the racism that was leveled against them,” Alvarez says. “They deserve credit. I feel they deserve a statue outside of Florida Field. And I don’t say that lightly.”

People tell him sometimes that he’s a hero or a civil rights icon or something else that embarrasses him. He says, “I just tried my hardest and you don’t think of all these things.”

In addition to homecoming at Florida, George also got to speak to the kids at Jesuit. They have a couple of pictures of him on the wall, he says. He looked around at that team, and it struck him that half the kids or more are black.

“And I said, right on. That really makes me feel good.”