by CD Davidson Heirs | March 19, 2020

Is This Florida Cracker Design Style Making a Comeback?

Haase Design pairs contemporary desires with the architecture of Old Florida.

David Haase sees music in architecture. It’s a melody found in the lighting of a room, the perspective he wants to create—it’s almost as if the notes were playing out on the page as he sketches an idea. And David’s specialty, what’s known as Florida “cracker” architecture, is like putting jazz onto the page because, as he says, “it’s born out of the region.”

David, 52, is an architect based in Gainesville. He runs a custom house design studio with his father, Ronald, called Haase Design. Ronald, known as “Ron,” is in his mid-80s and is a professor emeritus of the University of Florida School of Architecture.

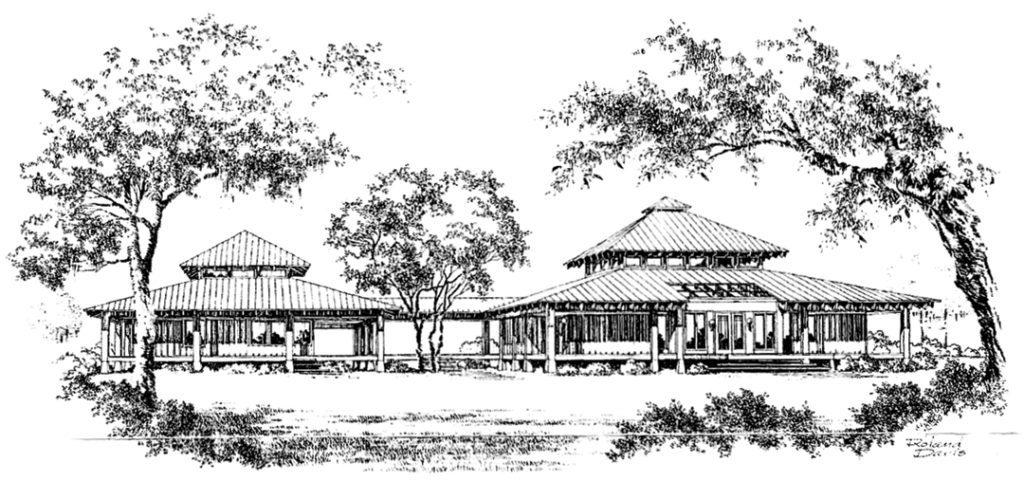

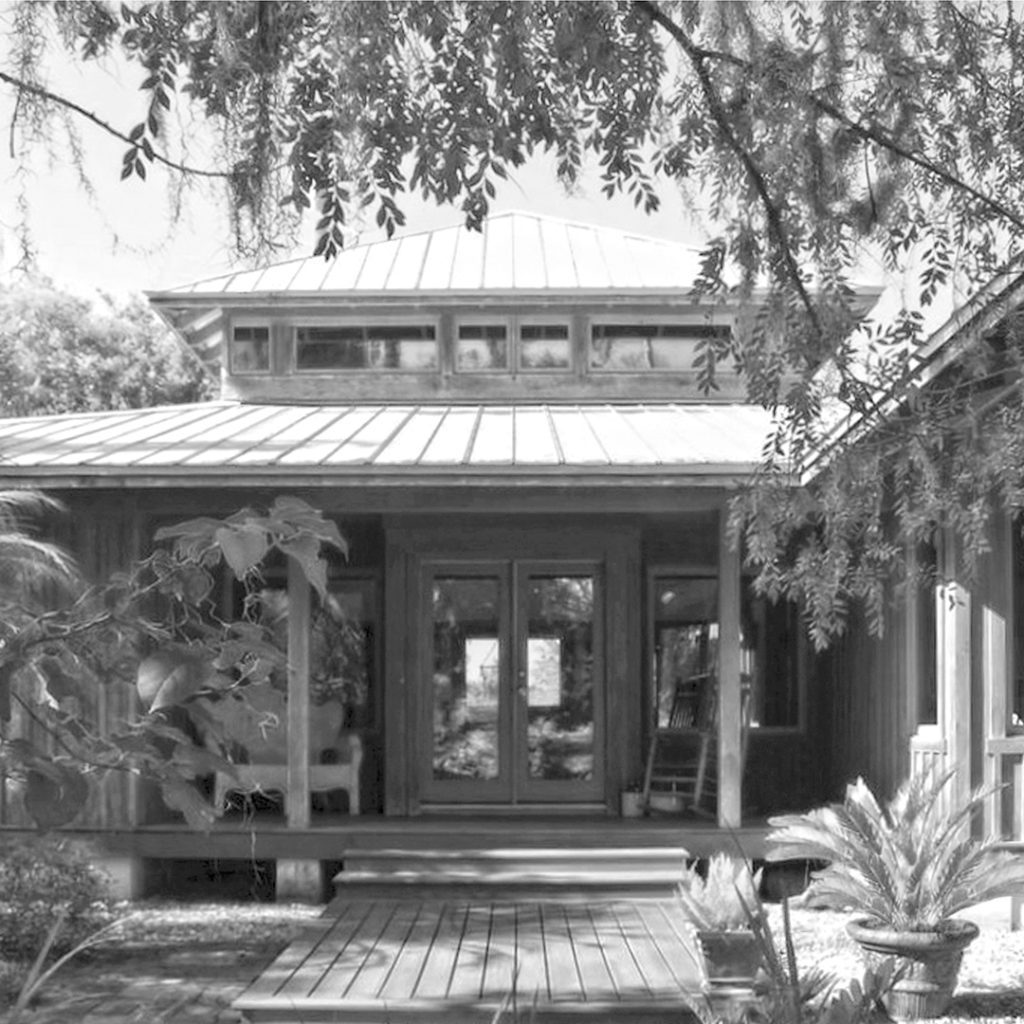

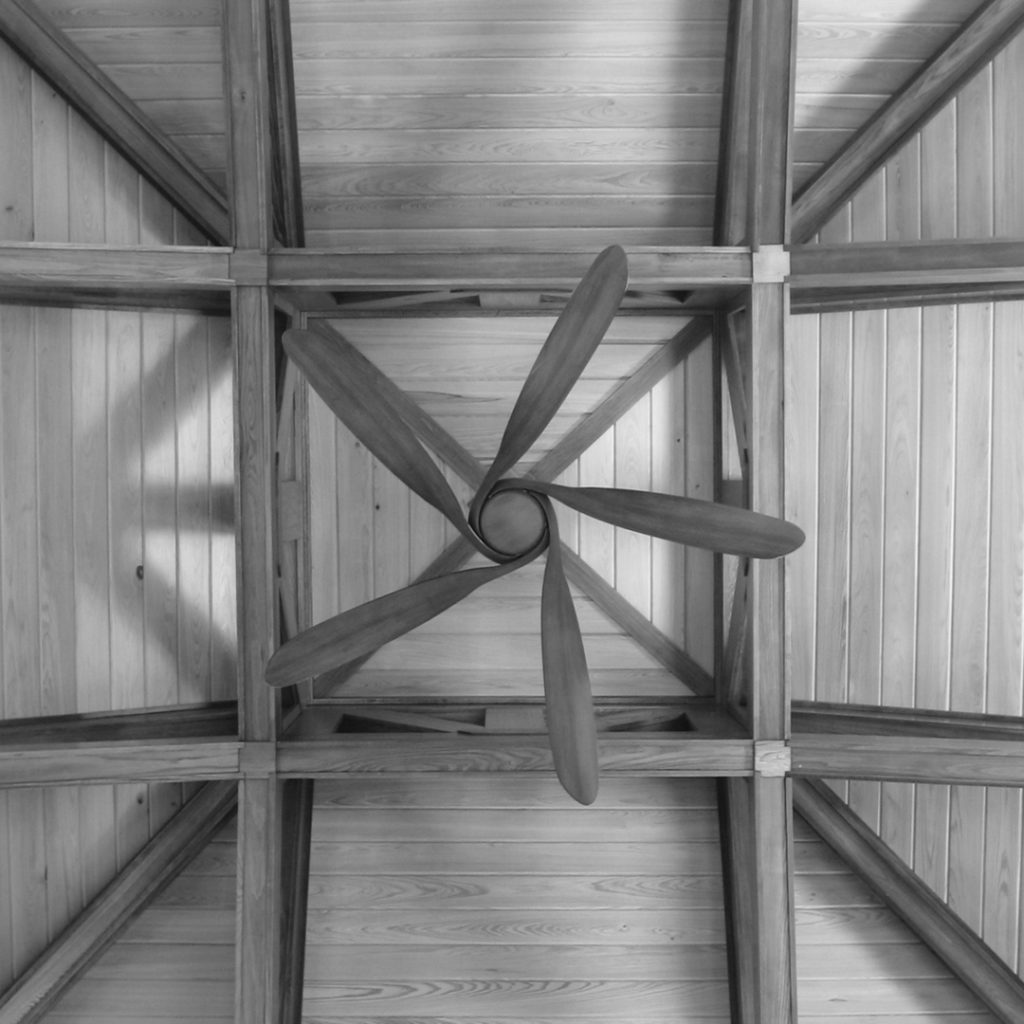

The duo collaborates on designing custom houses that belong to a place and account for the issues of our time. With deep overhangs and shady porches, the houses they create harken back to the years of early Spanish settlers. Boasting vaulted ceilings and clerestory windows to bring in natural light and cool air, the houses are built to interact with the environment around them.

In the late 1970s, David and his family moved from New Hampshire down to Gainesville. The family was pursuing inspiration in this patchwork state, and David was a preteen.

“Living close to nature suddenly seemed more elusive than I had thought it would be,” Ron told the Orlando Sentinel in 1986, when the family arrived to find everyone shut up inside with their air conditioners on.

Despite the surprise, the elder Haase pursued his passion for sculpting houses tied to the land, earning multiple grants and awards for his projects. In the early ’90s, Ron published Classic Cracker: Florida’s Wood-Frame Vernacular Architecture. The book describes what a cracker house looks like, how a family turns a house into a home through design and Ron’s personal journey with the style.

The father’s passion caught hold of the younger Haase. David went on to study architecture at Louisiana State University and at the University of Kansas. As he moved into his career, David joined large architectural firms in Kansas City, Missouri, designing casinos and banks, Caribbean resorts and U.S. multifamily homes. But he found himself missing the subtle elegance of Florida’s landscape and came home to Melrose.

It was then that the father-son pair began to formally collaborate on projects—and Haase Design began.

“I was born to do it,” David says of designing buildings. “There’s the analytics of architecture, and then there’s the aesthetics of art and design. Those, to me, mesh together pretty well with how I experience the world.”

Cracker-style architecture is one of four styles David describes as common to the Sunshine State. The other three are Spanish, such as the tanned mission homes found in St. Augustine; Sarasota, which produces “white, efficient boxes”; and the swinging curves of art deco, born out of Miami’s South Beach.

Much like jazz, David says, cracker houses are an American invention.

To describe one of the houses is to explain what makes Florida—well, Florida. The ground is moist, the climate subtropical, so Spanish settlers built their houses up off the ground, David explains. Mosquitoes and other insects whined with the threat of disease, so houses were often built with cypress wood, a natural bug repellent common to the region. Homes developed high ceilings and well-placed windows to combat the summer heat.

“A lot of times it comes back to elegant simplicity,” he says of the houses’ charm.

“Cracker” has multiple connotations, David explains.

One, which William Shakespeare uses in his King John play, means a braggart. Another, more sinister meaning refers to a slave driver “cracking” a whip. Yet another could have its beginnings in the sound of “cracking” corn husks.

But a fourth use of the word, and David’s favorite because of the image it paints, is of cattle drivers “cracking” whips while herding cows through Florida’s backcountry. Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León introduced cattle to Florida, and to North America, in 1521.

“When you are out in the wilderness as a settler and there’s no sound of cars or anything, you’re going to hear that ‘crack’ sound,” David says.

The Haase Design studio works with a range of clients, from those looking for more minimalist living to those wanting to build more than 5,000 square feet. The larger houses are challenging, David says, because cracker houses were built to evolve over time. Like reverse Russian nesting dolls, cracker houses began with a smaller room and developed outward as settlers’ families grew. Starting with a bigger foundation requires even more of an artist’s touch.

For the Haase projects, David says he is not trying to “recreate history.” He instead considers what his contemporary houses would look like if they had begun years ago and grown over time.

He is always curious what questions will define a house, no matter the style. For instance: “Where do you want the laundry room to go?”

David jokes that half his job is architecture and the other half is navigating personalities. Spouses rarely have the same ideas, he says—though many people choose to put the laundry room next to the kitchen.

The Haases have completed projects in Naples, near the Ocala National Forest, near Jacksonville and down the St. Johns River. Their work stretches from the Atlantic to the Gulf Coast, from South Florida to the Panhandle and even beyond the state line.

David has been asked for decades if cracker architecture is becoming more popular. His answer: it was never just a trend.

“That passive solar technology—shady porches, windows in the right place, natural light—those things are eternal,” he says.