by Moni Basu | February 24, 2020

Racing Icon Hurley Haywood Gets Real About His Personal Life & Career

The legendary life of the Brumos race car driver and the secrets he kept locked away until recently

Hurley Haywood, perhaps the greatest sports car endurance racer in history, has just returned home to St. Augustine.

He flew to Los Angeles to see his new baby, a 1960 Porsche 356 coupe. Haywood’s blue eyes light up with the joy of a child on Christmas morning as he talks about how renowned restorer Rod Emory is customizing the classic car with an updated suspension and modern motor technology.

Over the course of his storied racing career, Haywood drove every Porsche ever made, except the iconic 356, the first car Porsche manufactured in 1948. It’s no coincidence that Haywood was born that same year, destined to drive and later become an ambassador for the German automaker and its Jacksonville dealership, Brumos.

The Brumos name rose to fame under its racing banner. Both the dealership and the racing team, which competed in the International Motor Sports Association racing series, are gone now, but a recently opened museum, the Brumos Collection in Jacksonville, tells a sweeping story of automotive design and development through remarkable cars. They include the Porsches Haywood drove, instantly recognizable by the white, red and blue Brumos livery.

Haywood’s vintage 356 is expected to arrive from California in May; he had a lift installed in his two-car garage to accommodate his prized possessions. He has coveted the 356 since he was a boy, since he knew what a Porsche was but long before he earned a place in the highest echelons of sports car racing and became the stuff of legend, especially here in Florida.

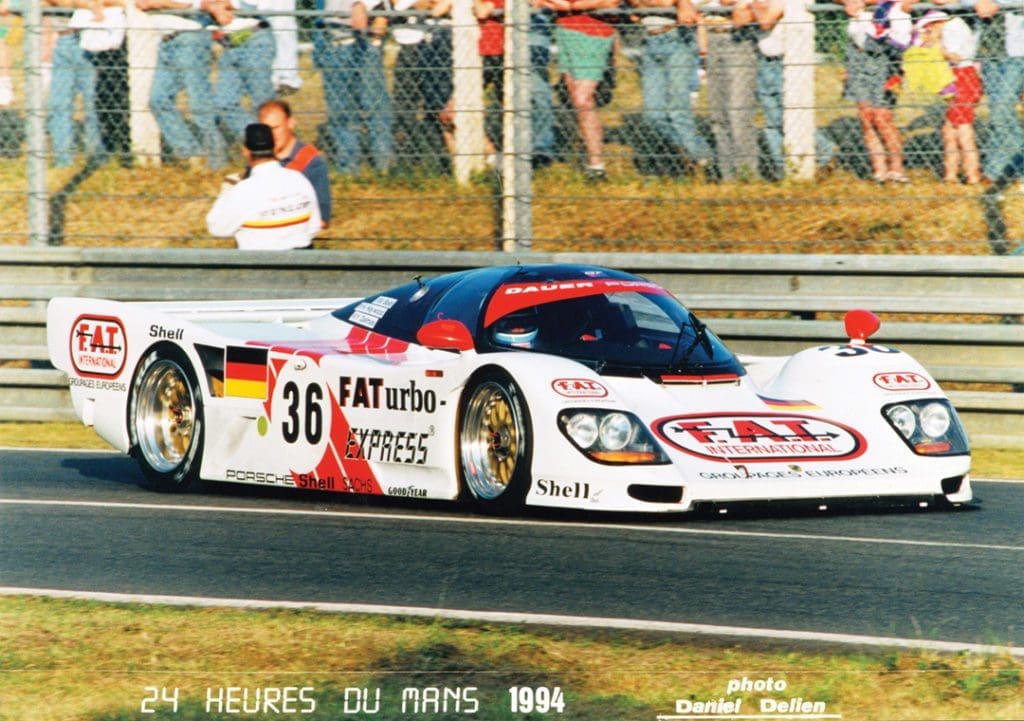

Haywood retired from racing in 2012, but throughout a career that spanned more than four decades, he amassed an astounding number of victories in the most intense form of motorsport: endurance racing. He won five times at the Rolex 24 at Daytona, three times at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and twice at the 12 Hours of Sebring.

Five Must-See Cars at the New Brumos Collection Museum in Jacksonville

From the moment he began racing in 1967, he was Superman immersed in a sport dripping with testosterone.

In the macho and glamorous world of speeding cars, Haywood, with his good looks, charm and elegance, was constantly surrounded by cameras and beautiful women. He’s been compared to Paul Newman, a friend of Haywood’s who shared his passion for fast cars. Haywood says people often took their likeness to mean he was the actor’s brother. I’ve seen photos and videos of Haywood, sometimes shirtless, hoisting trophies and kissing pageant queens, models and Playboy bunnies.

Back then, car racing was all about selling speed and sex. And Haywood played the role perfectly. It was a life second only to one he might have led in Hollywood, a life that forced Haywood to keep secrets.

SUPERMAN UNMASKED

“He looked like a movie star. He acted like a movie star,” says H.A. Branham, a sports author and director of the NASCAR Archives & Research Center. “He had an aura. He was big. And he backed it up by winning all the time.”

But it was the life Haywood lived off the track that fascinated me most. I admit to knowing little about car racing—watching gas-guzzling cars speed around a track and sometimes horrific crashes never appealed to me. I was more interested in speaking with the racing star about aspects of himself that he had kept hidden until recently.

Had I not seen the recent documentary Hurley, I might have been surprised by Haywood’s appearance and demeanor. At 71, he’s still Hollywood handsome but there’s no air of arrogance. Everything about him challenges the stereotype I have of a car racer. He’s soft-spoken and humble. I hardly feel I am in the presence of a man known the world over.

He is dressed casually in a blue Ralph Lauren polo and grey khakis and welcomes me into the waterfront house he built seven years ago. We walk through the kitchen and onto the back patio. It’s a warm January day, even for Florida, and we sit by a lap pool in our Ray-Bans, soaking in views of the Matanzas River and inlet spilling into the Atlantic. Haywood’s two English cocker spaniels, Indie and Watkins Glen—both named after race tracks—join us for a while until their barking poses too much of an interruption.

Haywood’s longtime partner, Steve Hill, stays out of the way, as he has done much of his life, working so quietly from home that I do not even realize he is here.

This is the part of the celebrity racer’s life that the public has rarely seen, and intentionally so. Until Haywood’s memoir was published two years ago, few people outside of his inner circle knew he was gay. That fact became more widely circulated with the 2019 release of the documentary, executive produced by actor Patrick Dempsey, himself a racer who was mentored by Haywood.

“It’s not easy to talk about,” Haywood says on film about his sexual identity. “This is the first time I’ve talked about this. To anybody. Publicly.”

He’d met Hill in 1979 at a Jacksonville bar on his way back from Christmas vacation in his hometown of Chicago. But they were never open about their relationship. Hill should have been atop a race car with Haywood on Victory Lane. He should have been at every celebration alongside the wives and girlfriends of the racers. Instead he watched the person he loved from behind a chain-link fence, with the rest of the crowd. Both men knew it had to be that way to preserve Haywood’s career. To come out as gay in the racing world might have been a death knell.

When I finally meet Hill, he tells me he is still an intensely private person. He never liked racing and had no idea who Haywood was when they first met.

“I still don’t like car racing, but I became a fan of Hurley’s,” Hill laughs.

Haywood says he resisted being interviewed on film about their relationship. But friends convinced him that it would help others. That is essentially why Haywood finally decided to come out, why he chose to reveal his true identity at this stage of his life, after all those years when he had carefully protected his public persona.

A few years ago, a high school senior was writing a paper about the business of racing and came to interview Haywood at the Brumos dealership, where he was then a vice president.

“He got about halfway through the interview, stopped cold in his tracks and said, ‘I need your help,’” Haywood says.

The teenager told Haywood he was gay and sensed Haywood was, too. He said he had been bullied all his life. He woke up every morning in despair and even contemplated suicide. In that moment, Haywood knew he could help by voicing his own story. It was the very first time Haywood had admitted to a stranger that he was gay.

“‘One thing you have to remember as you go through life is this: It’s not what you are, but who you are,’” Haywood told the teenager. “‘You can do anything you want if you put your mind to it. Just think positively and don’t give up.’”

Haywood never heard back from the student but about two years later his mother called. She told Haywood that he had saved her son’s life. Her words got to Haywood. He realized that if he could help one kid, he had the power to help many more.

“That’s kind of the reason why the film was started and why I agreed to do the book,” he says.

But that was just part of it. Success, Haywood believes, depends on the man or woman who stands behind you through your career. For Haywood, that meant coming clean about the love in his life.

“I just didn’t want to lie about it anymore,” he says in one of several poignant moments of the film.

Haywood’s biggest regret remains that he went through his glory years at the track without acknowledging his partner.

“I wish I had been able to share my life 100 percent with him,” he says. “But America was just not ready for that. It would have not only been difficult for me, but difficult for the fans who loved me and also difficult for Steve.”

Dempsey believes that the film not only communicated an important message from Haywood but also helped tell the story of motor sports in a completely different way, one that was compelling and human.

“And that I think is really important right now in the world that we live in,” says Dempsey, who honed his own racing skills under the tutelage of Haywood all the way to the podium, placing second in his class in 2015 at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the world’s oldest and most rigorous endurance race.

Still, Haywood was worried about the repercussions of making such a public declaration of his sexuality. He thought there would be a backlash, that longtime fans would feel betrayed, angry even. Maybe his reputation as one of the world’s greatest race car drivers would crumble in an instant.

“But that was not the case,” he says. “I guess the world has changed. People are more accepting of different lifestyles.”

A HAIRPIN TURN

Haywood grew up in Chicago, where his social circles were considerably less accepting. He came from wealth, and as a boy, he spent time on one of the family’s seven farms outside of Chicago. He found himself surrounded by roads and developed a fascination for cars at an early age. By the time he was 12, he was behind the wheel of a 1948 Studebaker truck. The farm foreman constructed a special seat and blocks for the pedals so that little Haywood could maneuver it.

“I drove that car successfully without getting caught until I was 16 and was able to get a regular license,” Haywood says with pride.

He may have broken the law, but the experience proved invaluable. He became a skilled driver before he graduated from high school. He understood the mechanics of understeering, oversteering and all the other intricacies of controlling a car.

Haywood bought a Corvette and left home in 1967 to study business administration at Jacksonville University. He’s lived in Florida ever since then.

Soon after, he got his big break when he met racer Peter Gregg, then the owner of Brumos. (He bought the dealership in 1964 from Hubert Brundage.) Gregg was so driven to win that his nickname was Peter Perfect. He showed up at an autocross in a Porsche 911 with a team of assistants. That didn’t faze Haywood; he bested Gregg in his Corvette.

Impressed with Haywood’s skills, Gregg took the young race car driver under his wing. Haywood’s first major race was with Gregg in 1969, in a Brumos car in the Six Hours of Watkins Glen. They won the GT portion. By then, the revving of engines, the smell of fumes, and the exhilaration of driving a sports car at more than 200 miles per hour had been ingrained in Haywood.

He was pumped to race more, to chalk up more wins, when he received the dread letter that was mailed that year to 850,000 other American men his age: a draft notice.

Haywood tells me that his family was established enough that they could have pulled strings and found a way out of Vietnam. But Haywood had friends who were killed in the war; he felt compelled to serve and deployed as a specialist third class, working as an assistant to an airfield commander stationed south of Saigon.

“The country has asked me to go fight a war,” he says. “Regardless of how I feel about it, it’s my duty to do that.”

After his tour, he remembers coming home with his duffle bag slung over his shoulder. At O’Hare, people were spitting on returning soldiers. It would be the only time Haywood felt scorned publicly.

He returned to Florida and rejoined Brumos. He and Gregg developed a close relationship and soon were known as the dream team of racing. Haywood credits the skills he acquired in the Army as a reason for his success. He had learned how to take orders without doubting; he’d learned ultimate discipline.

“He had a God-given gift and that makes him special and a cut above everybody else,” Dempsey says to me. “He was also very disciplined and developed that to the highest potential for himself. And then transcended the sport because of that.”

SECRETS TO HIS SUCCESS

Haywood drove in 15 races, sometimes 20, a year. Some were 24 hours long. Others 12 or six. Most were three. They required much more than just speed. Haywood had to learn the complex choreography of switching drivers and how to adapt to constantly changing situations.

“In endurance racing, you often race at night,” says Branham, the author and former Tampa Bay Times reporter who covered auto racing. “When Hurley raced at Daytona, we didn’t even have lights.

“You may have to race in both cold and warm conditions, wet and dry, nighttime and day,” Branham says. “It’s almost like you are several different drivers all at once.”

It’s easy to let emotion and enthusiasm overtake you when you’re flying around a turn at 220 miles per hour, Haywood says. It’s so easy to chase the car in front of you at any cost and override better judgment. He recalls the Porsche reps giving him stern advice: “You’re going to drive a really fast car, a car that can win the race. But we will not win unless you make zero mistakes.”

In many ways, Hurley says, car racing is like a game of chess. It requires a driver to look at the long-term goals and consider how to win the war, not just one battle.

“You have to look so far ahead at the move you are going to make,” Haywood says. “You can’t afford to make any foolish moves.”

“What was the key to Hurley Haywood’s success?” I ask.

“It’s a very simple answer,” he says without hesitation.

“It’s being patient and waiting for the opportunity to avail itself to make a move. And being able to adapt to change. Every lap, every corner is different than the last time you went through. If you are only locked into one way of doing something, you will never move forward.”

And there were a few other ingredients to success as well. Haywood always made sure he had chewing gum. It helped keep his mouth hydrated—there was no water in the cars back then and in a three-hour race, he stood to lose five pounds of weight that could only be regained through an intravenous drip. And even though there was a threat of choking, the cool, minty gum helped calm Haywood down.

It’s a habit he passed onto Dempsey, who jokes about how both he and Haywood are always at the ready at a race to hand each other some gum.

Haywood also believed in superstition. He learned from the legendary racer A.J. Foyt that the color green was bad luck in the racing world.

“I never asked him why,” Haywood says. “I just never wore anything green during a race.”

“There was a regimen I did before every race,” Haywood adds. “There were certain steps I would take. There were some superstitious things I believed in.”

I grow curious. How exciting that I am about to learn Haywood’s deepest racing secrets.

“Oh no. I’m not going to tell you what they were,” he says.

Somewhat disappointed, I ask him instead about the thrill of it all. What does it feel like to be in the driver’s seat?

“It would be impossible for me to use the English language to describe what that feels like,” Haywood says.

Were you ever afraid? I ask.

“Fear? Yes. Without fear, you would crash,” he replies. “You would make stupid mistakes. You might get away with it one or two times but eventually it would catch up with you.

“When it’s raining and you’re going at 220 miles an hour and you can’t see the nose of your car, that’s scary. But you’ve got to hold your foot down. Drivers have that sixth sense about where danger lies.”

Haywood’s partnership with Gregg lasted a decade. But Gregg was battling depression and the constant pressures of perfection wore him down. On a December day in 1980, Gregg ended his life. It was a shock to Haywood. He lost the person who was like a brother to him, the mentor who had taught him everything.

Three years later, Haywood crashed his car in a race in Canada. It shattered his left leg and took two-and-a-half years to heal. But against his doctor’s advice, Haywood was back in the driver’s seat four months later. It was the only time in his career that he wasn’t driving a Porsche; he couldn’t push the clutch pedal. Instead, he raced in a Jaguar equipped with a gear box without a clutch.

Haywood still keeps his left leg bandaged below the knee.

“Every step I take, I feel it.”

Haywood doesn’t race any more, except for fun. The Brumos brand is gone after the dealership was sold a few years ago. He’s still the Porsche man, representing the car maker in various ways and training young drivers at its academy. Two years ago, Porsche celebrated milestone birthdays for the

company and Haywood. Both had turned 70.

After our interview, Haywood walks me out to my car.

“Oh, I like that,” he says upon seeing my Mini Cooper sprinkled with red daisies. An honor, I think, that Haywood should approve of my little car.

“Let me show you what a Mini Moke looks like,” he says, opening up the garage to reveal the blue recreational vehicle parked next to a Porsche Panamera hybrid. Above us is the lift that will soon hold his restored vintage 356.

It’s been almost eight years since Haywood raced, but I can see his love for cars burns eternal.

I ask Haywood one last question. He had told me how important home was to him. This is where he could leave the sexy, speedy racing star behind and be Hurley again. This is where he could be with the man he loves. So why did he and Hill choose this particular spot in St. Augustine to live out the rest of their lives?

I think about his response as I drive away from this historic town. And it makes me laugh. He had always wanted to live in a place, he told me, where he could walk to the dry-cleaners, shops, restaurants—everywhere, really. Where he wouldn’t have to get in a car.

HURLEY’S FLORIDA FAVES

• • • • • 1 • • • • •

Favorite scenic drive in Florida?

HH: A1A from Amelia Island to Daytona. You go through the marshes and take the ferry across the river. There are a lot of great places to stop for lunch.

• • • • • 2 • • • • •

Must-have band on your road trip playlist?

HH: Billy Joel or Elton John. They both have a nice beat to them that makes driving kind of fun. I don’t listen to music a lot when I’m driving. I just like the sound of the road, especially when I’m driving a nice car.

• • • • • 3 • • • • •

If you could vacation anywhere in Florida, where would you go?

HH: I have a friend who has a beautiful piece of property in Hobe Sound. If I had to choose a place to hang out, that’s where I’d go.

• • • • • 4 • • • • •

Favorite Florida outdoor activity (besides racing)?

HH: Jaguars football games. I like it more when they’re winning.

• • • • • 5 • • • • •

Favorite hometown restaurant or hangout?

HH: The Blue Hen in St. Augustine. It’s a place where a lot of locals go. They have a great breakfast and lunch.

• • • • • 6 • • • • •

Favorite race to watch in Florida?

HH: Rolex 24 at Daytona

• • • • • 7 • • • • •

What’s a place in Florida you’ve never visited but always wanted

to go?

HH: Sanibel Island