by Bucky McMahon | November 26, 2018

For The Love Of Dogs (and Quail Hunting)

A man’s passion for “big-going dogs” sustains the tradition of one of the nation’s toughest field trials on Florida prairie.

You’d think it was electrified, the way the dog exits the box. Launched by a pure essence of bird-lust, distilled through decades of selective breeding, the big-boned, black-spotted English pointer hits the ground at a sprint and tears off down the trail, paws and claws kicking up rooster tails of white Florida sand. There goes Chinquapin Reward, alias “Pete,” clearly a dog with a lot of gumption, a big-goer, a dog that will “run off, but not quite,” as they say in the bird dog–handling trade.

At once, Slade Sykes, manager of Chinquapin Farm, a 7,000-acre private quail-hunting reserve outside Lake City commences his “handler’s song.” “Hey ho! Hey ho! Come here, Pete! C’mere, Pete, m’Pete, m’Pete! Heyo!” His yodeling cries echo through the pines. But there’s no sign of Pete.

For this demo of bird dog prowess, we have driven out a little way into the hunting grounds from the deluxe, if noisome, kennels, where some 60 English pointers clamored to be included in the mission. Sykes selected three: the 8-year-old veteran Pete, a two-time all-age champion at the field trials held here at Chinquapin Farm; a younger dog, Chinquapin Heir, not yet a “derby,” or 2 year old; and little Eve, an endearing, corkscrewing English cocker, just because she loves to ride. Sykes, a brawny, 40-year-old lifelong outdoorsman, deftly loads the beasts into what everyone here still calls “the old man’s hunting truck,” remembering Thompson Baker, who made his fortune in the construction materials business and founded Chinquapin Farm. Custom-made for the late patriarch, the vehicle is an update of the old hunting plantation mule-drawn wagon: a Chevy 2500HD pickup rigged with safari-style seats atop the bed, gun racks alongside and 10 gleaming steel dog boxes below. Indeed, all the facilities here, from the high-ceilinged kennels cooled by overhead fans to the stables and tack, shine with quality and meticulous attention to detail.

Where we stopped at the crest of a rolling hill provides a good long view of pristine Florida wire grass prairie. The early sun sends golden shafts through cathedral columns of 100-year-old longleaf pines that rise from a dense scrub of crotolaria and partridge pea and chinquapin, the farm’s namesake, with its spiny pods. It’s the first day of October, but summer growth still obscures the tufts of wire grass—the sine qua non of prime wild quail habitat—and just after dawn it’s already hot. The first frost, when it comes, will knock down the weeds and set the stage for some of the finest bobwhite quail hunting in the entire U.S. But shooting here is for guests of the family and for the second-tier dogs. For the best of the best, cooler weather means field trial season and grueling tests of bird dog stamina and class. Since the early 1970s, holding the Florida Open All-Age Championship at Chinquapin Farm has been the singular passion of the elder scion, Ted Baker, and the raison d’etre for the dogs, the horses and the carefully conserved land itself.

And here at last comes champion Pete, still at a gallop, tongue flung out like a jaunty pink scarf. He’s made a wide “cast,” foraging for the secretive little ground birds he was born to find but trained not to touch. We can watch and admire Pete now, bounding through the brush like a nuclear-powered jackrabbit. “It’s always amazed me how they do it,” Sykes says. “The air is full of pollen, their heads are off the ground, they’re moving fast, but somehow they still scent quail. It’s a God-given gift.”

The gifts of the Baker clan have long been hard work and the shrewd business acumen that turned Florida sand and lime rock into gold. Thompson Baker founded his construction materials business in 1931, not a propitious time to start a company, and then had to suspend operations to enlist and fight in the Second World War. Returning a decorated vet, he partnered with his former business rival, Jim Shands, and rebuilt his company. With the national postwar boom and Florida’s dramatic growth in population and construction, Baker, along with sons Ted and John, stewarded Florida Rock Industries Inc. into a juggernaut, mining raw materials at 23 locations from Florida to Maryland and spinning off multiple subsidiary businesses.

Read about the prolific writer Tom Word and his depiction of the sporting life.

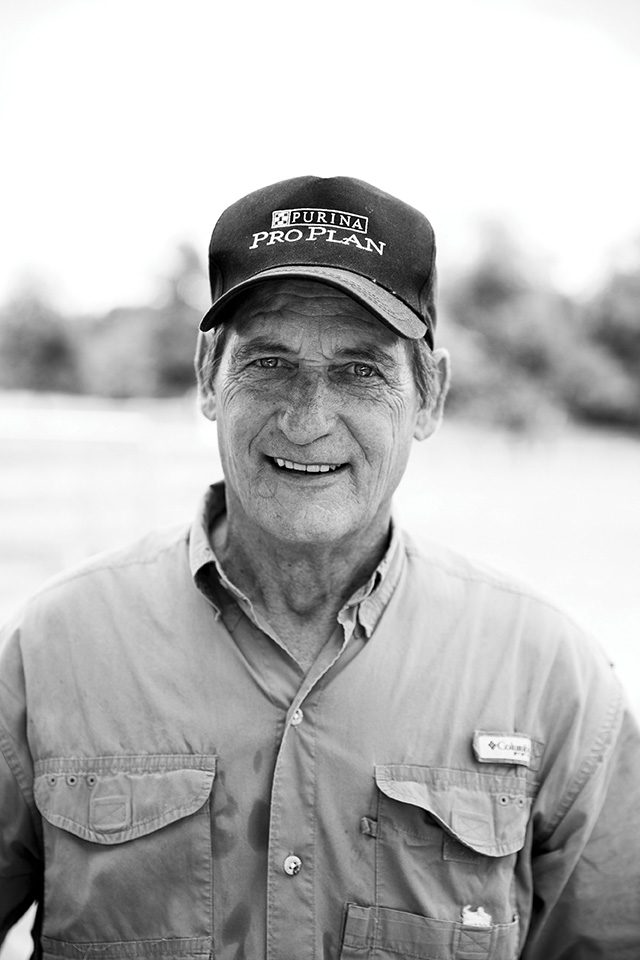

The Jacksonville-based Bakers, avid hunters, were drawn to the piney woods west of Lake City by the promise of good quail shooting. Ted Baker, now 83, recalls hunting on the land that would become Chinquapin Farm with his dad and his brother John when they were just kids. In those simpler times, they would stay in motels in Lake City and hunt on foot rather than horseback. But Thompson Baker saw the potential of the land, which was owned by absentee timber companies and small woodland cattle operations (activities detrimental to quail), both as a quail-hunting reserve and a business tool, and began leasing and then buying sections as they became available. By the time Ted and John were adults and helping run the business, the Bakers were hosting quail shooting weekends with Wall Street masters of the universe and prominent politicians. As Ted Baker likes to tell it, the land became “the company’s best salesman.”

“You can learn a lot about a person when you spend a couple of days hunting with them,” Ted Baker said. “You learn who you can trust.”

He recalled with a jovial growl some of the luminaries who came to shoot during the schmoozing heydays. Governor Bob Graham arrived, rather too ceremoniously, with full security detail in tow, losing style points. “And he couldn’t hit a bird to save his life.” By contrast, Lawton Chiles drove himself to the shoot in an old pickup. “He was hours late. Said he got pulled over by the police in Georgia,” Baker remembered with a chuckle. “Had to call for reinforcements.”

I’d met up with Ted Baker at the Big House, located on a rise at the end of a two-mile gravel driveway. It’s not really all that “big,” but it is impressive all the same: a four-bedroom modernist concrete and pine structure worthy of an Architectural Digest feature, overlooking a man-made fishing pond. On the paneled walls of the main living area hang fifteen portraits of Chinquapin’s champion bird dogs, all major field trial winners. Baker sometimes uses a cane, which sports another portrait, the carved likeness of Rocky, or “the Rock,” a favorite retriever. “Just a sweet little dog, rode in a special box on the truck,” Baker said of his beloved Brittany, who may have been pampered but was very good at his quail-retrieving job. The mining tycoon used to cook the Rock a hamburger for lunch every day; the loyal retriever lies now in a well-maintained gravesite behind the Big House.

We took a four-wheel-drive tour of the backcountry, Baker at the wheel, jouncing along sand tracks and firebreaks, dodging gopher tortoises and flushing quail as we followed some of the field trial courses. Occasionally, we passed a watering trough strategically placed so that an overheated pointer, running hard in unseasonable weather, can plunge in and out like an otter, barely breaking stride. Baker’s seen it 6 degrees here on the day of a trial, he said, and he’s seen it 90 degrees. That’s Florida.

Like what you read? Click here to subscribe.

As we passed tall pines lightly charred from the base to about a man’s height, and swaths of mowed area beside the scraggly wild, Baker described the constant care the land requires to keep it from turning into an impenetrable jungle. Every spring, some 60 percent of the acreage is burned, the prescribed fires mimicking unfettered lightning strikes and Native American land management practices dating back to ancient times. The pines and the wire grass thrive with fire, while the upstart hardwoods perish. Some areas are mowed, others disked, the soil broken up to encourage new growth, which attracts insects—quail food. Supplemental feed, in the form of both planted crops and scattered seed, is provided for the quail year-round.

The bobwhite quail is one of the most thoroughly studied wildlife species in the U.S., and the science of managing land for wild quail is well established, though the results remain unpredictable—quail populations continue to decline. There are some 80 quail hunting plantations in North Florida and southern Georgia, totaling around 300,000 acres. Some date back to the Reconstruction Era, when the legendary robber barons from the North claimed the spoils of King Cotton for their winter shooting preserves; other large spreads, like Ted Turner’s Avalon, and the Bakers’ Chinquapin Farm, represent fresh infusions of fortunes into the genteel hunting lifestyle. Collectively, these properties create what writer T. Edward Nickens calls “accidental reserves of biodiversity.” What’s good for quail, it turns out, is good for many native species. And what bobwhite quail prefer is the past—the perennial landscape of the South, the pine wood and wire grass savannas that once covered 150,000 square miles. The trick, then, is turning back the clock to a time before the land was divvied into bits by agriculture and development. Turning back the clock—and holding it there.

In 2007, the Bakers sold Florida Rock Industries to Vulcan Materials Company for $4.6 billion. “That’s billion,” Ted Baker repeated, and he was right to do so; I’d heard million. “For that amount of money, we had to sell; the shareholders would’ve sued us if we didn’t,” he told me. The sale marked the end of one era for Chinquapin Farm—the farm as business tool—but by then Baker had long been head over heels for “big-going dogs” and the competitions that prove them. He’d first caught the field trial fever back in the late 1960s. Though“Dad and John didn’t care a bit about it,” he was impressed by the professional dog trainers and handlers he’d met in the quail shooting milieu.

Baker joined the Marines, following in his father’s footsteps, and after his honorable discharge he began a small enterprise with a local trainer named Earl Weems. He and Weems would choose a young dog—“just a puppy without the sense to get in out of the rain”—and, in a matter of eight or 10 months, coax a fine hunting dog from the raw material. Then they’d sell it to Baker’s father, “the old man,” for $500, good money in those days. The Baker family’s string of hunting dogs had pedigrees dating back to the 1930s, and Ted took great pleasure in developing the line and entering its best in competitions.

“‘My dog’s better than your dog!’ Well, you could argue that all day. That’s how it started.”

A field trial for pointers is a simulated bird hunt with plenty of distractions to bedevil even the most disciplined dogs: In addition to 40 or so spectators on horseback, there are the rival handlers, scouts and a competing dog scouring the same course for coveys of quail. As they dash and leap over brush and briar, the dogs are judged not only on their ability to find birds but also on style and enthusiasm. “It’s a class act,” Ray Warren, Chinquapin Farm’s head dog trainer, told me. “It’s not just dog vs. dog but also handler vs. handler. Whoever puts on the best show takes the money and the trophy.” Once the dog locates the birds, it must hold its point, tail erect, statue-still, until the handler has flushed the birds and fired a blank shot (“steady to wing and shot,” in the lingo).

A pointer will point instinctively, Warren explained to me. But a dog’s psychology isn’t so different from a person’s. “That dog is thinking, ‘How can I rush in there and get those birds and eat ’em?’” The indignities pile on, as the pointer has to watch shooters shoot them, and another dog—a Labrador or other retriever—fetch them. There’s nothing natural about that.

“It takes a steady hand to make a steady dog,” Warren said. A well-broke dog will hold point for up to 15 minutes, which must seem an eternity in dog time. Besides freezing at point, winning the trial often comes down to that indefinable quality: class. “All I can tell you is you know it when you see it,” Warren said. “The hair stands up on the back of your neck. That’s what makes it so exciting.”

When I visited Chinquapin Farm, some of the young dogs had just come back from summering in South Dakota. It’s a tradition in the rarefied world of field trialing for the dogs to escape the Southern humidity so that they can train year-round and build their stamina. During a trial, dogs are on the move throughout an hour-long heat—“I’m talking about flat-out running, too,” Baker said. The trainers themselves are often on the move. Baker compared them to golf pros, traveling tourney to tourney, gambling that their dog will win back the $1,000 entry fee ten times over. Sometimes they train horses as well as dogs or sell a few puppies on the side, cobbling together a living, and holding on to an old, old lifestyle, at the heart of which is the animal–human bond.

“When you’re in the field trial business, you’re in the horse business, too,” Baker explained. After driving through some of the rugged field trial courses, we toured the 18-horse stable—with adjoining heart-of-pine paneled clubhouse—admiring the Tennessee walkers and inhaling the good smells of horse and hay. Then back through the kennels, where each dog stood to greet us with a resounding welcome. Dogs, horses, and land: Combining them all in a field trial is more complicated than just shooting birds. There was, naturally, a learning curve.

Baker’s first experience as a field trial organizer got off to shaky start: A participating dog owner complained about the lack of coherent courses at Chinquapin. Offended at first, Baker soon cooled down, took the man’s advice and began to refine the testing grounds. He laid out six courses along hog-back ridges where judges and observers could easily see the dogs as they made their sweeping casts in search of quail. By 1979, after several years of apprenticeship and holding qualifying meets, Baker advanced to the big leagues, hosting the Florida Open All-Age Championship biannually (in November and March), contributing his own money to supplement the purse and keep the entry fees reasonable, and throwing an oyster roast bash at the Big House as a joyful send-off for all participants. He’s been praised by the sport’s periodical of note, American Field Sporting Dog & Field Trial News, for his “devotion to excellence in preparing the grounds and inviting sound judges.” And his dogs have proved they have the stuff of champions.

A wild quail lives scarcely a year; a high-strung hunting dog a little over a decade. The longer-lived generations of men may outlast the values and culture they were born to. Environmentalists of the plantation belt fear that the shooting life and the vast tracts of land that foster it, with all its expensive appurtenances—the horses, the dogs, the festivities that center around the quest for the little wild birds—may not survive into the next generation. Baker knows that change will come to Chinquapin Farm. His younger brother, John, co-owner, isn’t a field trial man. Ted’s late wife, Ann, liked the social aspects of it, visiting with folks—“You know how girls are”—during both the shooting parties and the field trials, but didn’t care much about the breeding and training of pointers. He recognizes his passion as an eccentricity he has no wish to impose on his heirs. No doubt Chinquapin Farm will go on into the next generation as a shooting reserve, the land preserved for pine and wire grass and quail. As for the field trials, he’s not so sure.

“Well, you have to be crazy!” is how he put it. Crazy enough to hear music in the sound of 60 kenneled hounds baying, to see the special beauty, the glory, of a dog performing at the peak of its potential.

Like Chinquapin Reward—big ol’ Pete—who is showing us his stuff, his stamina, in the stifling heat, in the smothering humidity of not-quite autumn. He’s answered Slade Sykes’s song, come back to the shrill of the handler’s whistle. And now, like a divining rod, he’s homing in, making quick dashes back and forth. The birds are here. No, here. Here. Right here. Pete freezes. His tail stands stiff with hardly a quiver, like an inverted comma, holding the moment in quotes. The quail burst into the sky; Slade Sykes fires the shotgun. Pete holds firm.