by Steve Dollar | August 27, 2018

Florida Man’s Movie Star Moments

Is it the mind-numbing humidity, the alligator-infested swamps, the potential for mischief on 1,350 miles of coastline or something wilder that explains why people in the Sunshine State act in dark and strange ways? Filmmakers have been obsessed with that essential Florida mystery since motion pictures began.

Long before the Internet made him famous, Florida Man was ready for his close-up. The meme only became a viral sensation a few years ago, a perverse homage to those news headlines about aberrant, often drug-induced, behaviors across the peninsula that always begin with the fateful words “Florida man”: as in, “Florida man arrested after driving 110 mph while naked with 3 women in a Cadillac” and “Florida man who had sex with dolphin claims it seduced him.”

Thanks to sunshine laws that make arrest records available to the press, such reports have for decades been a staple of daily newspapers across the state. No one knew him by that name back then, but once smartphones and social media arrived, so did Florida Man, who even has his own Twitter account. The mysterious entity flourished, and flourishes now, as a kind of rebel spirit, an avatar of untempered gonzo. If you look at the history of Florida filmmaking, you can see him everywhere—so much unruly dark matter infusing the cinematic imagination with twisted tales of social deviance and extreme eccentricity.

Movies have been made in Florida almost since motion picture cameras first rolled in the United States. Jacksonville was a hotbed of production during the silent era, welcoming its first movie studio in 1908, and with the 1916 launch of Norman Studios, it became a pioneering site for films made for African-American audiences. Neighboring St. Augustine also boomed and played an essential role in the history of the American horror film.

Now lost, the 1915 Life Without Soul was groundbreaking. It was the first American feature film based on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and conjured a European setting in coastal northeast Florida. Even at the dawn of the art form, tales of madness, obsession, delirium and crimes against nature were dominant in movies made in and about the Sunshine State.

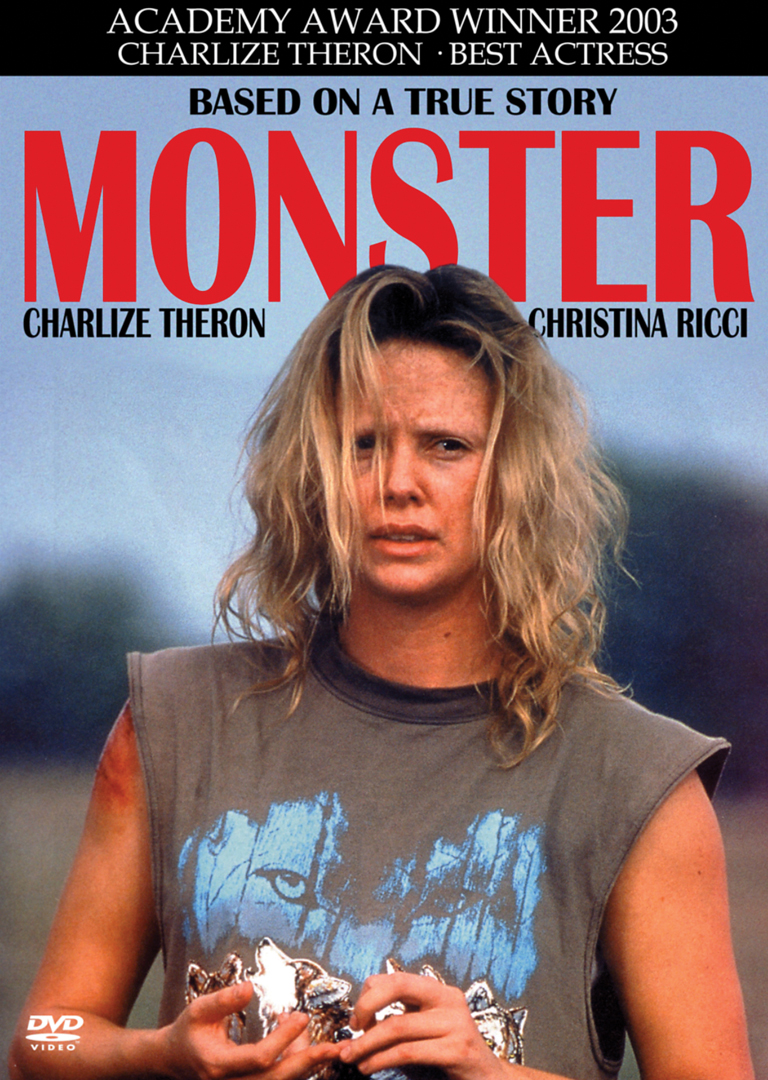

Over the decades, Florida has been portrayed onscreen as the land of serial killers (Monster and its documentary source, Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer), recovering child molesters (the documentary Pervert Park), zombies (Day of the Dead, I Eat Your Skin), cannibals engaged in Confederate reenactments (Two Thousand Maniacs), a mutant amphibian apocalypse (Frogs), lovestruck amphibian dude-bros (Creature from the Black Lagoon shot in Wakulla Springs), horny, homicidal teenagers (Bully, Spring Breakers, Wild Things), drug runners (Cocaine Cowboys, Square Grouper: The Godfathers of Ganja), disillusioned male strippers (Magic Mike), disillusioned bodybuilders-turned-kidnappers (Pain & Gain), grinning, pretty-boy psychopaths (Miami Blues, Something Wild), sexy, topless aliens (Nude on the Moon), pubescent voyeurs (Porky’s), experimental farming methods that turn a man into a turkey-headed monster (Blood Freak, a cautionary tale), man-eating alligators (Adaptation), man-eating cobra gators (CobraGator) and good, old-fashioned man-eaters (Body Heat, with Kathleen Turner as a scheming seductress who manipulates half-bright FSU Law School grad William Hurt into a murder plot).

OUT ON A LIMB

Thoughts of this unusual legacy came to mind during my visit to April’s Tribeca Film Festival, a springtime launching pad for a wealth of foreign-language art house films, American indies and documentaries. Presided over by Robert De Niro, the festival attracts scores of Hollywood celebrities and rising stars to mug for the paparazzi on its red carpets and tipple the night away at seemingly bottomless open bars and private parties. Such scenes have been familiar to me for the last 30 years in my on-again, off-again role as a film critic for major newspapers, from The Atlanta Journal-Constitution to The Wall Street Journal, and a host of websites. From Sundance to Toronto to Berlin and beyond, the film festival circuit is a well-traveled one. This was my sixth or seventh visit to Tribeca, a festival whose main theatrical venue is in Chelsea and, for about three years, in my nearly literal backyard. Yet, to my surprise, I saw something I’d never seen before. Right there, in the strobe-like pop of a camera’s flash, I could swear I glimpsed Florida Man. Or someone very much like him.

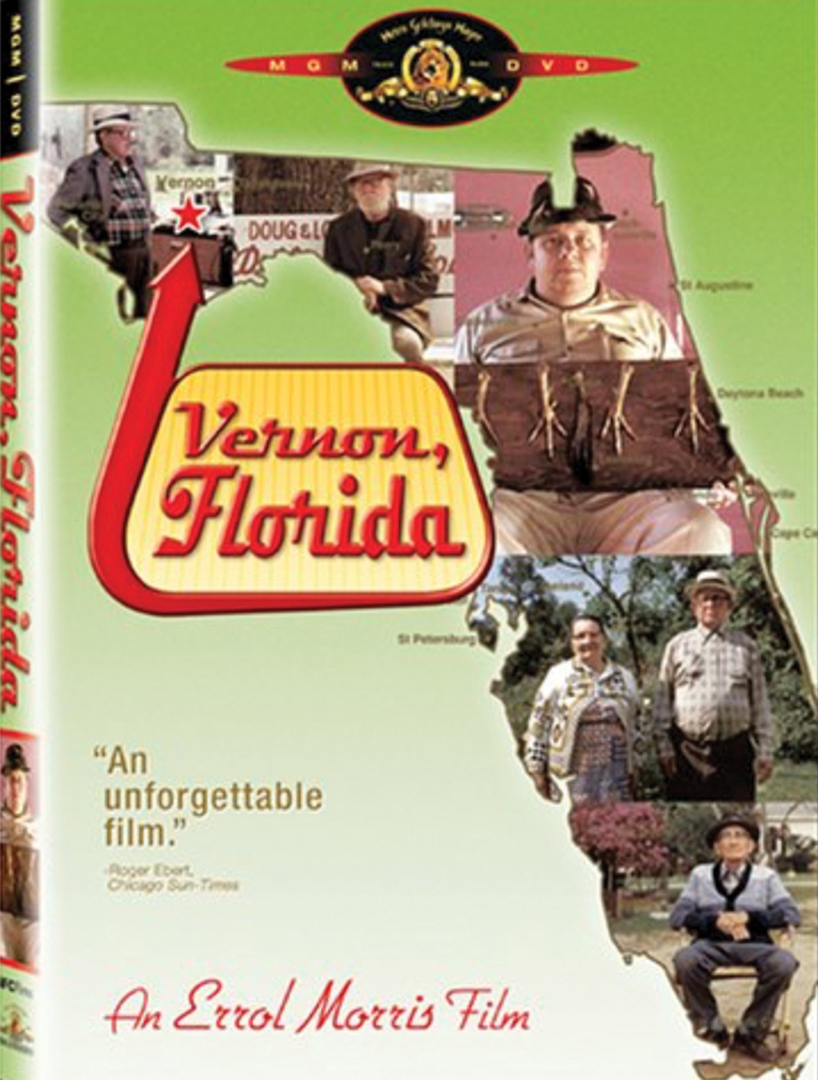

He’s embodied by the subjects of White Tide: The Legend of Culebra, easily the most outrageous film at this year’s festival. The documentary is a rollicking evocation of native Floridian weirdness that owes no small debt to early Errol Morris. The filmmaker may not be a household name, but he pretty much invented the true-crime mystery format so beloved of Netflix binge-watchers. His classic The Thin Blue Line, about the murder of a Dallas, Texas, policeman, saved a man from the electric chair through its meticulous investigation of the evidence that led the wrong suspect to be convicted. But it’s Morris’s 1981 documentary Vernon, Florida that should earn the director a place in the state’s hall of fame. Morris originally intended to make a film called Nub City, a nickname for the tiny Panhandle town where, in the 1950s and ’60s, residents took to crudely amputating their own limbs for insurance payouts. When his life was threatened during a 1977 visit, the filmmaker fled.

Like what you read? Click here to subscribe.

“It’s the only time that I’ve been beaten up,” Morris confesses in an interview from the Criterion Collection’s 2015 rerelease of the film. “I sort of got the idea that interviewing nubbies was not the way to go.” He circled back years later, this time focused on some of Vernon’s more colorful citizens.

Four decades after Morris first set eyes on it, there still isn’t a lot to Vernon. The population estimate falls shy of 700 souls, a sum that hasn’t wavered significantly in 70 years. The opening frames of the documentary offer a template of Panhandle Floridiana: A battered Ford pickup truck rolls down an empty, ill-maintained street, insecticide billowing out in mosquito-killing clouds behind it. Yellow caution lights blink in vacant witness, shaded by oak trees dripping with Spanish moss. If there’s not much to see, there’s plenty to talk about, it seems, as Morris engages an array of indefatigable conversationalists and one quavery-voiced codger he calls “the epistemologist of the swamp.” Many of them are elderly and sweetly out of their heads. They include an obsessive hunter who discourses on “that turkey feeling” (“They’re a smart bird, … the smartest we got in this country”), a sand collector, a connoisseur of wrigglers and a minister who runs unlikely analytical circles around the word “therefore.” Their logic may be peculiar, yet it is rarely less than fantastic, even magical. As the film’s resident deep thinker, Albert Bitterling, says at the start of the film, “Reality … you mean this is the real world? I never thought of that.”

The characters in White Tide exist between the crosshairs of those two movies, as the true-crime doc reenacts an outlandish drug caper gone haywire. The film reconstructs its shaggy dog saga with the full participation of its main subject, guileless and big-hearted Central Florida real estate developer Rodney Hyden, whose fortunes tumbled in the aftermath of the 2008 financial meltdown. Down on his luck and giddy with get-rich-quick-again dreams, Hyden hears a far-fetched campfire story from one of his beer-drinking, pot-smoking buddies. The friend is an aging hippie who claims to have discovered some 15 years before a $2 million stash of cocaine on the beach of an obscure Puerto Rican island, then freaked out and buried it under the sand. Hyden enlists his drug-addled slacker sidekick Andy in a quest to recover this seemingly mythic—and utterly illegal—treasure, which puts them both in contact with some dubious new acquaintances.

Do not, repeat do not, run to Google now and type in Hyden’s name. You’ll spoil all the fun that White Tide intends to swamp you with. I’m not going to ease the suspense with too many more plot points, which unfold in a manner as methodical and attenuated as any good fish story—or the best novel Carl Hiaasen never wrote. Hyden’s everyman charisma and filmmaker Theo Love’s attention to microscopic detail hook the audience well past any sensible suspension of disbelief. By the time the film’s portly protagonist delivers his impersonation of Al Pacino in Scarface and recounts his meetings with a mysterious pilot named “Carlos,” it’s fair to wonder if the whole production isn’t some extravagant gag. White Tide is designed as pure entertainment, not philosophical discourse, yet, as with Morris’s work, the film functions as an interrogation of the “truth,” as the bumbling —to me, anyway—conspirators get helplessly caught up in something that is plainly an outrageous fabrication, yet can’t reason their way out of it and just keep digging themselves into a deeper hole. What’s tricky to discern is whether they have taken insane risks for the lure of forbidden cash, or because it’s the best campfire hoohah they’ll ever be able to relate. It’s a wild ride and a quintessential Florida epic.

“There seems to be some sort of underbelly,” says Larry Fessenden, a New York-based genre film producer who also co-starred in one of the classic Florida outlaw movies, River of Grass. The 1994 debut film of writer-director Kelly Reichardt (Wendy and Lucy, Certain Women), rereleased in 2016 and widely available to stream, emulates vintage film noir in the desperate tale of two lovers on the lam, fleeing the fuzz after a random act of violence. Except no one is dead, the lovers aren’t in love and the police aren’t looking that hard to find them.

“It’s kids on the run without them getting anywhere.” The anti-drama, as Fessenden calls it, evokes Marjory Stoneman Douglas’s 1947 book about the Everglades as it soaks in the ambience of fringy Dade County, where Reichardt, daughter of a crime scene investigator and a narcotics agent, grew up. It’s the best sort of Florida movie, one that uses a familiar plot formula, but discards predictability like a lukewarm Icee to capture something essential in the humid, mosquito-ridden, sun-bleached, nothing-much of it all.

A VIOLENT PARADISE

There’s something raw and existential in the Florida landscape that has a potent appeal to independent filmmakers; a sense of lostness, of kitsch masquerading as dreams.

“It’s the false promise of the sun and the fake happiness of Disney World,” Fessenden suggests. “I love that alligators crawl across the golf courses as a matter of routine.”

Filmmakers from Jim Jarmusch (Stranger Than Paradise) to Sean Baker (The Florida Project) would likely agree. And it’s not only hipster New Yorkers who fetishize Florida’s exotic locales. Exploitation film legend William Grefé made a career maximizing the moccasin-infested funk of the Everglades, producing a string of sordid thrillers and creature features in the 1960s and ’70s. He scandalized and titillated a generation of drive-in date nights with movies like The Wild Rebels, The Psychedelic Priest, The Death Curse of Tartu and The Naked Zoo (which starred Rita Hayworth in her penultimate screen role). Along with such aesthetic outliers as splatter horror pioneer Herschell Gordon Lewis and Doris Wishman, the grande dame of 1960s sexploitation, Grefé captured something of Florida’s untamable mystery, unconsciously elevated by low budgets and grindhouse excess.

Decades later, that mystery abides. St. Petersburg native Amy Seimetz, part of the same Florida State University crew that includes Oscar-winning Moonlight director Barry Jenkins, made her own Florida project in 2012. Sun Don’t Shine—a perfect title for a latter-day noir shot along U.S. Highway 19 as it ramps down toward Tampa Bay. Seimetz and her cinematographer Jay Keitel make humid poetry of tacky beach motels and sticky car seats. The film steers its blood-simple lovers, speeding away from the scene of their crime with the evidence weighing heavy in the trunk of their car, toward Weeki Wachee Springs, mapping coastal peculiarities with a sensitivity to both myth and consequence.

As Seimetz told a journalist around the time her film premiered at the South by Southwest film festival in Austin, Texas, it wasn’t as if she had to stretch the facts for the sake of fiction. “Growing up in Florida, most of the insane crimes I would read about were all taking place in Florida. All of the stuff where you’d read about it and say, ‘What the fuck? Who would do that?’—that happens in Florida. To me, the main factor is that the heat is so oppressive and it makes you crazy. It builds up so much angst, and you can’t think during it. The crime rate goes up in the middle of summer. Florida is this amazing clash of paradise and violence.”

Florida Man may not have a date with Oscar anytime soon. So many of the most pungent, er … evocative screen incarnations of his rowdy-ass soul have been in low-budget horror, action and crime films that don’t usually get a lot of industry respect. Yet, as even a brief survey of Florida film history reveals, he’s more than a meme; he’s a movie star.