by Steve Dollar | November 23, 2017

Author Jeff VanderMeer: From Books to Big Screen

With a movie adaptation of his New York Times best-seller Annihilation hitting the big screen this February, author Jeff VanderMeer takes us into the Future and the Florida wilderness that inspired a book trilogy.

Not too long after he moved to Tallahassee some 25 years ago, Jeff VanderMeer took a hike in the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, a 68,000-acre habitat winding along 45 miles of Florida’s Gulf Coast. It’s a mecca for all manner of migratory birds and home to an ark’s worth of hairy, scaly, sleek and sharp-clawed beasts, from that Sunshine State spirit animal the alligator to the Florida panther VanderMeer spied during one of his myriad walks there.

That day, however, the young novelist got caught in one of those raging gully washers that rise up out of an otherwise placid Panhandle afternoon and come shredding through the lush canopies of foliage.

“I didn’t expect the storm,” VanderMeer remembers. “It started storming, and I got really turned around. Usually, you can see the road leading out toward the lighthouse. I had no idea where I was. It was a very revelatory experience, just to be out there and feel completely lost and much farther from civilization than you actually are.”

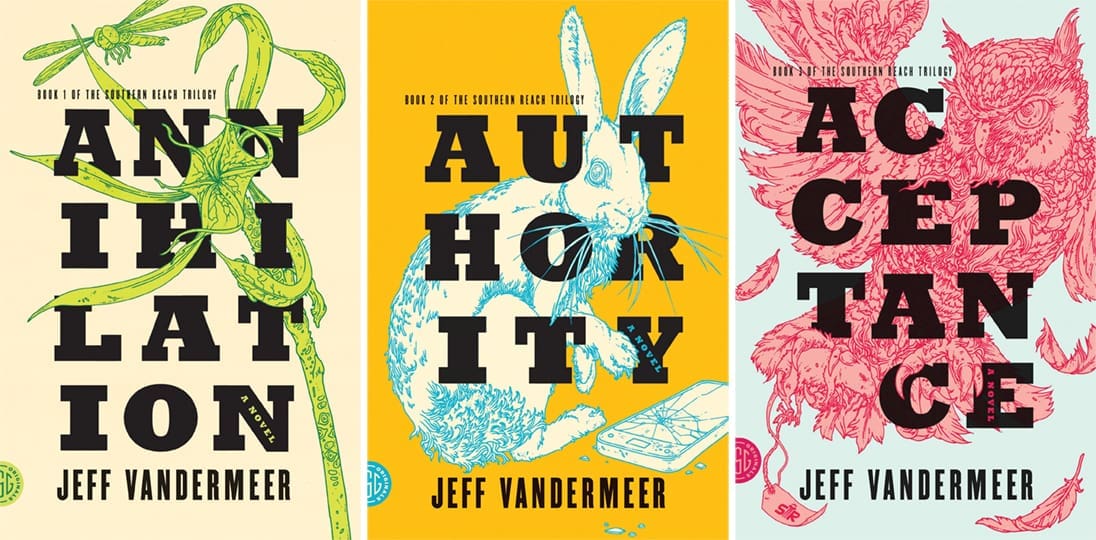

That experience, among so many other daylong excursions in St. Marks and other preserves, provided inspiration for VanderMeer’s 2014 novel Annihilation, part of a trilogy that vaulted the prolific writer onto the New York Times best-seller list. In February, moviegoers worldwide will share those sensations with the release of a major Hollywood adaptation of the book, written and directed by Alex Garland of Ex Machina fame. Natalie Portman stars as The Biologist, one member of a survey team dispatched by a secretive government agency to explore otherworldly phenomena in Area X, a forbidden zone pervaded by a strange force.

VanderMeer followed Annihilation with two sequels that continue the storyline. Authority is a black-comedy riff on bureaucratic dysfunction, and Acceptance is a metaphysical page-turner that circles back to the beginnings of Area X in a whirling, hypnagogic fashion but does little to decode its mystery.

“When I wrote Area X, I didn’t have to do any research,” VanderMeer says. “It was a place I already knew.”

That deep familiarity is apparent in VanderMeer’s prose, which shifts between mortal absurdity and kaleidoscopic reverie—between, say, the earthbound and the transcendental. The approach got him christened “the weird Thoreau” by The New Yorker. “They imagine nature, both human and wild, in a new way,” wrote critic Joshua Rothman about Annihilation and its companion volumes. “And they take a surprising approach to language: in addition to being confounding science-fiction novels, they are fractured, lyrical love letters to Florida’s mossy northern coast.”

Like what you read? Click here to subscribe.

On a breezy Sunday morning in early autumn, VanderMeer sits at an empty picnic table in San Luis Mission Park in Tallahassee. It’s another favorite spot to hike. There’s an elusive hawk he’s always happy to glimpse and a slight possibility of stumbling across museum staff in Spanish Mission era costumes, although such unusual occasions always seem less improbable when they happen to VanderMeer. After a peripatetic childhood and, now, intensive travel on book tours, these Floridian vistas ground him with a sense of place and supply boundless inspiration.

“There are so many different kinds of environments and landscapes,” he says of St. Marks. “You start out with pretty traditional pine forests, and then you go out into black swampy areas, which are very uncanny and unsettling. There’s this quality of silence. The water absorbs certain sounds. The background chatter falls away. Even the birds’ communication falls away. Except you hear every once in a while something you don’t know what the heck it is. And then you go more towards what looks like holding ponds but really it’s a raised berm with freshwater or brackish minilakes on one side and then the marsh reeds leading out to the sea on the other side, which is amazing. Because you have this sea of reeds and these islands of trees coming out of it … it really does look like islands even though it’s all land. It looks almost prehistoric, some of that vegetation, fairly primitive kinds of plants and trees, some of it. And then of course you can go out to the beach if you want. It changes so much between the winter and the spring. In the winter, you can be convinced that you are somewhere in southern Scotland.”

So perhaps it’s strangely fitting that the movie version of Annihilation had to expensively reimagine this promiscuous wilderness in a swampy region of the United Kingdom. VanderMeer is not involved in the Paramount Pictures production, which also stars Jennifer Jason Leigh, Gina Rodriguez, Tessa Thompson and Oscar Isaac. He considers it a separate entity from the source material, which has been reshaped by Garland, a novelist and screenwriter known for his work with Danny Boyle on Sunshine and 28 Days Later. This is Garland’s second feature as a director.

“It really anchors in a sense of horror and the unknown in many spectacularly effective and tactile ways,” VanderMeer says of Annihilation. “Despite the vicissitudes of Hollywood, it’s still unusual that it’s basically an arthouse movie coming out this way.” When he visited the movie’s set in England, VanderMeer was impressed by how closely the production team recreated coastal Northwest Florida. In fact, it was a little mind-blowing.

“It is a very surreal and weird experience all around to have something that’s the most personal thing I’ve ever written, almost like a diary entry in terms of landscape description, become this totally other thing.”

At one point, VanderMeer recalls with a laugh, he pointed to a mailbox covered in lichen and told Garland it looked exactly like his own. “And he gave me this look, like, ‘Are you from a family of hoarders? Do you never clean off your mailbox?’ And I’m like, ‘It’s North Florida, man! It doesn’t matter. I can do it one day, and it’ll be back the next day.’”

VanderMeer spent much of his childhood in Fiji, where his entomologist father did research on rhinoceros beetles. Later, when they lived in Ithaca, New York, it was moths. When the family moved to Gainesville, the elder VanderMeer took on that Southern menace, the fire ant, while working at the University of Florida and the United States Department of Agriculture. “He found an enzyme in poison frogs that works well in fire ant prevention,” VanderMeer says. “He’s known for separating out, very laboriously, pheromones in ants.” The author’s mother was an artist and biological illustrator. “I always had one foot in my dad’s lab and one foot in my mom’s studio.”

VanderMeer began publishing his own work—including poetry—and the work of others in his teens in self-created literary magazines with names like Chimera Connection and Jabberwocky. He also organized literary events, sometimes poaching major guests who already had speaking engagements at UF. He studied journalism and Latin American history at the university, but day jobs and writing took up too much of his time, so he left school.

He was 20 when Ann Kennedy drove from Tallahassee to Gainesville to meet him face-to-face. Like Jeff, she was immersed in the world of independent publishing. They had gotten to know each other through the community of science fiction and fantasy enthusiasts who wrote, edited and distributed homemade zines and journals. She had published Jeff’s work as well, “but I didn’t publish everything he sent me.”

It was the pre-web days of the late 1980s, and much of their communication was in letters. “I had no idea that he was as young as he was. He had been publishing for at least five years,” says Ann, now an editor whose efforts won her a Hugo Award, the Oscar of science fiction literature. She remembers bringing Jeff a bottle of champagne to celebrate the launch of his new magazine. “When I met him, I realized he wasn’t even old enough to drink the champagne!”

Nonetheless, he impressed Ann as a major talent. “His work was so vivid to me, so right there,” she says. “His imagination, the actual stories and characters he created, were so unique. Some of those stories would stab you right in the heart with the strength of the emotion.”

After Jeff moved to Tallahassee in 1992, their separate literary endeavors gradually began to overlap. “After a while, it just made sense for us to publicly state we were working together,” says Ann. In 2007, the pair edited their first anthology together, Best American Fantasy. “It was my first time seeing my name on a book in the bookstore. It was very exciting for me,” Ann says. Since then, Jeff and Ann married and went on to edit a library shelf’s worth of science fiction and fantasy anthologies. Among those titles are The New Weird, Steampunk, The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities, The Time Traveler’s Almanac, The Kosher Guide to Imaginary Animals and last year’s The Big Book of Science Fiction—a 1,200-page epic whose revisionist perspective expands what we think of when we think of sci-fi, from first-time translations of Russian, Eastern European and Latin American authors to a short story by W.E.B. Du Bois, the African-American social leader and public intellectual who co-founded the NAACP.

That eclectic catalog of work can make his fiction hard to label. “I’ve never really felt part of the various literary movements I’ve been stuck with. I felt like I’ve just been passing through,” says VanderMeer, who has a publishing deal with literary powerhouse Farrar, Straus and Giroux. “They’ve stuck me with everything from straight-up science fiction to new weird, weird, speculative, slipstream—which is a really weird, amorphous term—magic realism, anything that seems to be hot or rediscovered at a particular time.”

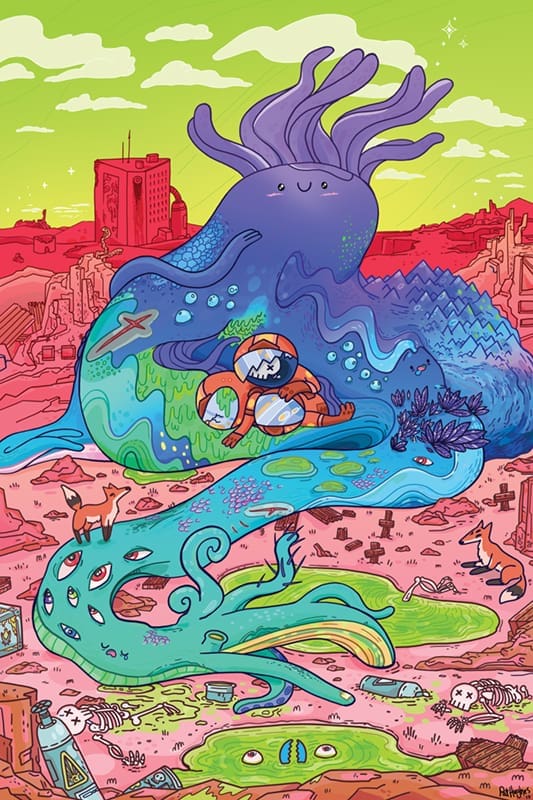

Lately, VanderMeer has been associated with a new term: eco-fiction. His new novel Borne tells the story of Rachel, a climate refugee scavenging in a ruined city. The city is menaced by a giant flying bear named Mord, the mutant product of the Company, a collapsed biotech firm whose creations are both bizarre and terrible. Borne, a phosphorescent octopod that can mutate into other life forms and objects at will, is another one of the Company’s experiments. Rachel adopts it, and tries to mother it, but things get complicated.

“I had this image of a woman reaching out to a sea anemone wrapped in seaweed,” says VanderMeer, who has a way of sponging up the world around him and transforming it through free association, not unlike the creature Borne. In this case, he drew on his childhood in Fiji as a source, imagining that Rachel came from a similar place. “She was drawn to the creature because it was making her drawn to it and because it reminded her of where she grew up, which doesn’t exist anymore.” In VanderMeer’s visualization, the anemone wasn’t an anemone and the seaweed wasn’t seaweed, “but the matted fur of a giant bear … and as the scene panned out the bear flew off, and I realized we were in this desert city.” Borne is now also in line to become a movie, and VanderMeer will be more involved in the production process than he was with Annihilation. The novel is fantastical in many ways, but it also reflects the very real concerns that have been present since his first stories and have recently grown more urgent. A lot of Borne, he says, isn’t even fiction. “That’s the thing. If you haven’t been affected by climate change, you’re in somewhat of a privileged position at this point. And you absolutely have cities where multinationals come in, set up shop at the edge of town, suck the resources out to make products and ship everything overseas. That’s not too different from what’s happening in Borne, in terms of the Company.” A giant flying bear seems to be the stuff of fairy tales or, as VanderMeer suggests, something by the great Japanese filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki, known for the animated classic My Neighbor Totoro. It made for an entertaining prop when the VanderMeers toted a wood cutout of Mord on the Borne tour. Pause to contemplate our current moment, though, and it begins to seem entirely plausible. “We’re at a point with gene splicing where you might, in 10 years, have kindergarten classes creating small creatures,” the author says. “The ethics and morality of all this seems to be sliding to the wayside … this slippage between animal, product and art. When is an animal someone’s piece of art? When is it a product? When is it its own thing?”

Nothing VanderMeer writes is so painfully on-the-nose that it comes across as blatant social commentary. “People don’t like to be lectured, especially where you have cause and effect that isn’t always apparent. You have to be more subtle anyway,” he says. The trick is to engage readers on such a visceral level that they can feel what the character feels and “to trust the reader to enter a complex scenario where they might change their mind.” He’s trying to reach anyone “who says they believe in climate change but they think the crisis is 50 years down the road.”

In addition to other ongoing projects, VanderMeer is finishing a novel called Hummingbird Salamander. The title refers to a pair of stuffed animals that the main character discovers in a storage bin, the property of a mysterious dead woman who has left a key. A wormhole beckons, and soon an average American cubicle worker finds herself entangled in an unimaginable vortex of bioterrorism and wildlife trafficking. It’s set, VanderMeer says, about 10 seconds from now.

“The distance between our science-fiction future and our present is collapsing to the point that it doesn’t exist anymore,” he says. “We’re in the middle of this catastrophe, whether we recognize it or not.”