by Michael Adno | November 23, 2017

A Day on the Water and a Lifetime of Lessons with Florida Fishing Legend Flip Pallot

Flip Pallot forged a revered angling legacy in the backwater byways of the Sunshine State.

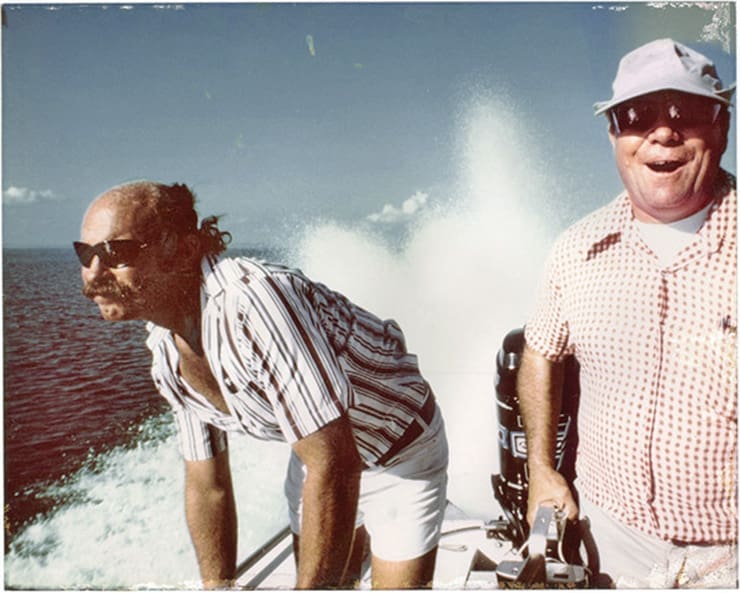

Slowly cutting through the Intracoastal Waterway north of Central Florida’s Mosquito Lagoon, Flip Pallot, 75, spun the steering wheel of his skiff to the east, looked left and right, and then gracefully put the boat on plane, weaving through a labyrinth of oyster beds and shallow shoals. Each pivot of the boat and tweak of the steering wheel seemed effortless, every drop of water beading off the rail in place. On the shoreline south of the historic Eldora settlement, live oaks draped in Spanish moss spilled into flatwoods dotted with cabbage palms. It was nothing short of magic. It was as though I’d traveled back in time and become a guest on Walker’s Cay Chronicles, the fishing program that Pallot ran from 1992 until 2006 on ESPN. In its 16-season run, with Pallot as its principal host and creator, the show gave rise to a whole new world of outdoor programming with its concoction of adventure, mystery and philosophy.

Pallot’s contributions to fly fishing and boat design—he has co-founded or consulted for multiple companies, including Hell’s Bay Boatworks—are simply overwhelming. He has inspired generations of outdoorsmen and continues to do so. “That show was one of the building blocks that became my life,” Pallot says. “It was the perfect seedbed for a lifestyle to spring from.” Out on the water, 25 years after the show first aired, I wanted to get a sense of how that came together.

Coming into a larger basin, Pallot stopped the boat, and we drifted across a flat flanked by a spoil island and a tall dune separating Mosquito Lagoon from the Atlantic. A tarpon rolled near the island. “Two fingers to the left,” Pallot pointed. A school of redfish churned in the shallows, agitating the surface into a coffee-colored froth. Manatees surfaced, and a group of porpoises flung mullet at each other. Pallot, clad in a button-up, sunglasses and a straw hat with a spray-painted camo pattern, sat contentedly as a flock of terns took off from a nearby oyster bed, stirring the soundscape. After a lifetime spent cultivating moments just like this one—his first trip into the Everglades was 60 years ago—he told me, “The most precious thing I’ve ever known is time. Just time. You can’t replenish it.”

Like what you read? Click here to subscribe.

At the tail end of the 19th century, Pallot’s grandfather arrived in South Florida on a stagecoach. He’d made the passage from Russia, through Europe and across the Atlantic, finally working his way down the East Coast after entering the country through Ellis Island. “We were South Florida people,” Pallot said. Both his mother and father were born in the region, and he grew up west of Krome Avenue in Homestead on a thumb of farmland jutting into the eastern Everglades. The periodic inflections of his dialect harken back to that time. “Snook” sounds like “snewk,” “creek” is pronounced “crik,” and “My-am-ah”—as Pallot says—wasn’t much of a city back then. Waiting in line at the movies was a social event; if you didn’t know the person in front of or behind you, you knew their cousin.

Early on, Pallot got a taste of the Everglades during fishing trips with his father. Later in life, he’d return again and again to those seemingly endless corridors. In 1961, he enrolled at the University of Miami, but he was drafted into the army as a linguist only a year later. Over the next five years, Pallot got a whiff of the far-off locales that would later become essential to his life and career. Back in Miami, he got a job at a bank and worked as a fishing guide on the weekends. He kept his desk job until 1976.

“I listened to people tell me why they should be given a loan,” he explained during one episode of his show. “I did this for a number of years, and all the time I knew something was missing from my life. Maybe if I hadn’t known about the magic that exists outdoors, I would have been OK behind that desk, but I did, and I had to get out before I forgot what it was like to be happy.”

SWEAT EQUITY

As a kid, Pallot cut his angling teeth with talents such as John Emery, Norman Duncan and Chico Fernandez. All three of these fishermen hold a special place in the annals of angling, but in South Florida they’re like deities, garnering as much deference as Pallot.

In 1959, Pallot met Fernandez at a local haunt, the Tackle Box. “He had this Cuban accent, and I’d never heard anything so cool in my life,” Pallot recalled. “And, shit, he had a fly rod.” Fernandez had just arrived stateside on a ferry from Havana, filling his Mercedes 190 SL with jazz records and fly rods as Fidel Castro forced out Cuban president Fulgencio Batista.

“There I was. I spoke English OK, but not very well—like Tarzan,” Fernandez joked. “We had an identical case for fly fishing and probably an identical income, which was almost none. So we made our own flies, modified reels, spliced fly lines. We had to learn everything.”

Eventually, they began renting tiny skiffs from a boat livery on Summerland Key called Speck’s. Later, Pallot and Emery would split the cost of an engine, and, when the owner sold the place, they bought a boat. Soon, a trailer followed, and Key West was within their reach. “Then it was game on,” Pallot said. “Suddenly, we had complete freedom.” They were young and hungry, with a burning desire to catch the big fish. “Those were our weapons,” Pallot said.

Oftentimes, they’d stake out Stu Apte’s house on Little Torch, gleaning what they could by watching him carry gear down to the dock. Apte, one of fly fishing’s legends, would become a household name through his achievements: modifying the blood knot, scouting far-off flats by airplane, guiding Joe Brooks, penning books and amassing world records like candy. “We’d just sit there and watch how he did everything,” Pallot said, a grin spreading across his face. “It was better than fishing.”

As Pallot recounted those formative years in his soft cadences, he gently put his hand on the push pole straddling his skiff and deemed it the greatest teacher in the world. “Every stroke you make is an investment—of your time, your physical effort,” he noted. “You’re going slowly enough to see the natural world, and eventually, all those things connect.”

GENERATIONS OF PROMISE

In 1964, Bernard “Lefty” Kreh took a job heading up the Metropolitan Tournament in South Florida, concurrently working for the Miami Herald as a fishing columnist. A few years later, he would co-found Florida Sportsman magazine. At that point—17 years after he learned to cast from Joe Brooks, the host of American Sportsman and the angler credited with the ascension of the sport—Kreh was a star in the then-small community, his name synonymous with the sport of fly fishing. But as a veteran exhibition shooter, Kreh also had unparalleled accuracy with a modified BB gun.

Only a week after he arrived in Miami from Maryland, a knock came at Kreh’s door. When he opened it, a young man said, “My name’s Flip Pallot, and I hear you can shoot aspirin tablets with a BB gun.” Pallot, 24, brought a bottle of 200 aspirin tablets, and Kreh showed him that a bead of oil dropped into the gun’s chamber would make it exponentially more precise. They started tossing the capsules into the air and shooting. “That was the first time I ever met him, and we became very close,” said Kreh. “I never realized I was teaching Flip anything. I learned a hell of a lot from him.”

At that point, Pallot was still wearing a suit and tie, spending his weeks doling out loans at a desk. But, as Kreh joked, “You couldn’t get a loan during tarpon season.”

In 1971, Jose Wejebe’s father contacted Kreh with a request to teach his teenage son how to cast a fly rod. Kreh coached Wejebe behind the Herald building. Wejebe would become one of the most unforgettable personalities in angling. “He was so into it that I gave him a fly rod, reel and line,” Kreh remembered. Eventually, Kreh introduced Wejebe to Pallot, and the two became close friends.

“He was such a nice kid that you couldn’t ignore him,” Pallot said. Five years later, in 1976, Wejebe decided to pursue guiding, but nobody would loan him the money for a truck, trailer and boat. Fortunately, Pallot did.

Pallot deemed those loans the best he’d ever made. “Certainly, I’m happier about those loans than any others because of who Jose turned out to be—what a great friend he turned out to be.” He cleared his throat and added, “He never missed a payment.”

Wejebe’s show Spanish Fly ran from 1995 to 2012 on the Outdoor Channel and presumably would have continued long after. However, in 2012, Wejebe perished when his plane crashed shortly after leaving the runway in Everglades City. Wejebe was one more link in this chain of talented anglers, from Brooks and Kreh to Apte and Pallot.

Pallot’s proximity to that flare of promise in Wejebe could have been the reason he traded his pen for a push pole, becoming a full-time guide in the early 1980s.

BUENOS AIRES TO THE BAHAMAS

In 1984, Pallot nudged his boat forward with a new client on the bow, Diane Rabreau. They were set to spend a half-day fishing, but, as he told Sarah Grigg of Fly Fisherman magazine, “I could smell her like a bird dog and was shot through with love.” And as Diane told me, “I liked everything he was saying, his presence, his voice, and I knew he liked me, so I took advantage of that.” Now Pallot’s wife, she explained that, although she hadn’t been exposed to that fly fishing side of Florida before meeting him, the more she went out, the more she wanted to know.

As a Pan American flight attendant, Diane spent exorbitant amounts of time pacing the narrow corridors of jetliners. On one trip, she got to talking with John Abplanalp. She mentioned her husband and gave Abplanalp their phone number. A little while later, Abplanalp saw Pallot on an episode of NBC’s Outdoor Life. He called immediately. His father, Robert Abplanalp, was the owner of Walker’s Cay, a small resort in the Bahamas, and he invited Pallot to come outfit the place with a fleet of skiffs and guides. As Diane explained, “One thing led to another, and we got sixteen years of a show thanks to one crazy, serendipitous day on a flight.”

Before creating Walker’s Cay Chronicles, Pallot appeared on episodes of American Sportsman and Outdoor Life. Orlando Wilson, an outdoor producer and host himself, approached Pallot to ask if he’d like to develop a saltwater fishing show. At the time, Mark Sosin was beginning to develop Mark Sosin’s Saltwater Journal, but other than that, “There was absolutely nothing on the horizon.” Pallot agreed with the caveat that he have independent control over the show’s content.

In the first year that Saltwater Angler ran, it surpassed the ratings of shows hosted by Roland Martin, Bill Dance and even Wilson. Pallot’s charm, paired with an unconventional approach to programming, lent the show a gravitas others couldn’t match. In response, Wilson took the reins, but in the second season, it withered.

With all that experience, Pallot approached the Abplanalps with an idea for a show that would eventually become Walker’s Cay Chronicles. Using the island as a jumping-off point, the Abplanalps funded the pilot and pitched the project to ESPN. “It was about the story, the relationship and the learning process. The whole idea of the show was to portray that,” Pallot said. And it did, in inventive ways that evoked the prose of Guy de la Valdene, Jim Harrison and Thomas McGuane—all close friends of Pallot’s. “He told a story about those places, and the fishing was just part of it. Walker’s—in most people’s minds, including mine—is the finest fishing show we’ve ever had,” Kreh said.

Much of that charm grew out of Pallot’s approach to guiding. As he explained, “Part of my package was a tremendous appreciation for the natural world. We’d stop to see an eagle or an orchid [or] go into a certain bay just to see flame vine.”

To get a sense of the show’s legacy, I called Mike Dawes, an accomplished angler, guide and filmmaker who grew up sleeping on the porch of his grandfather’s cabin in Deep Water Cay. “I remember the sense of adventure it provided,” he said. The show evoked a childish, awe-inspiring hope. And, for countless viewers, the ethos of Walker’s Cay Chronicles articulated something many were after but none could quite pin down. It made clear that the outdoors was a sort of beacon to return to—a kind of cathedral made of old-growth mangroves and basins filled with promise. Pallot’s reverence for these places became a new way of seeing the world.

IN THE REARVIEW

Now that conservation has become a buzzword, Pallot broods about the state of the angler’s relationship to the outdoors today—including his own. As he told me, “The issues snuck up on us. We thought it would never end.”

Pallot is the first to admit, “We did a miserable job of preserving the good ol’ days.” He cited a lack of awareness among his peers about the larger issues at hand, such as development, regulation and pollution. He believes the dangers of these issues could have been, and perhaps still can be, avoided. “If future generations are willing to settle for the fact that those were the ‘good ol’ days,’ then [depleted fisheries] is what they’ll have. But what they need to do is what we should have done: Get aggressive, get loud and get in the fight.”

His voice softened, and Pallot told me, “The downside of the attention these shows drew was the pressure on the resource, but my rejoinder is: If you don’t know something, you can’t love it. And if you don’t love something, you can’t protect it.”

In 1992, the Pallots left South Florida to settle in Mims, east of Orlando. “A hurricane drove us up here,” Pallot explained. Just after Walker’s Cay Chronicles began filming its first season, he and Kreh were scheduled to film an episode in the Everglades. Two days before Kreh was set to fly down, he called Pallot, concerned about a storm sliding through the Florida Straits. Pallot urged him not to worry about it: They’d have a hurricane party, and then, after the storm passed, the fishing might be really good. On the evening before Hurricane Andrew hit, the storm gathered strength. Despite law enforcement’s incessant reminders to evacuate, “Our people never left for hurricanes,” Pallot said of his family. “So—foolishly—we stayed.”

Two hours into the storm, the roof of their home was torn off like a piece of paper, “and, once the storm came inside, it was just a shipwreck.”

Taking cover in their bathtub beneath a waterlogged mattress, they hid there until the gales devolved into gusts at daybreak. “When I went outside, the devastation of that storm was just unspeakable,” Pallot remembered. “Our house was gone.

“In that period, we realized Miami was not what it once was,” Pallot said. Because their roots ran so deep in Homestead, leaving was a monumental decision for them, but the town had changed. In Mims, Flip and Diane felt like they were still in Florida—his Florida. “Time sort of stopped up here.”

When I pulled into the long narrow driveway of their home in July, I saw bright red buckeye flowers in full bloom on their front porch. Just as the legends have it, Pallot always keeps a buckeye seed in his pants pocket for good luck in the woods or on the water. He deemed it one of the “most antiquated Southern traditions.” But Southern superstition paired with ruthless pragmatism seems to have lent Pallot an unrelenting charm, and maybe that’s what has carried him so far.