by Craig Pittman | November 24, 2016

Forgotten Mermaids: Florida Manatees

The gentle manatee is now considered by many as “threatened,” not “endangered.” But is the sea cow’s proposed status downgrade a good thing?

One Saturday afternoon last January, a 10-year-old girl with blonde hair, a blue dress and a very determined manner marched to the front of an Orlando hotel ballroom carrying a pink stool. She plopped it down in front of a wooden lectern, stepped up and leaned toward a microphone. Her name is Megan Sorbo, and she had a message to deliver to the adults at the front of the room, employees of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Too many manatees, she said, keep getting hit by boats. Do you know, she asked, what it feels like to a manatee to be hit by a boat? She said it was “like a human getting hit by a bus.”

Sorbo was one of about 70 people gathered in that ballroom who wanted to convince the federal bureaucrats that the manatee should continue being listed as an endangered species. Another vocal contingent of perhaps 50 or so, many of them from a town in Citrus County where the economy is largely manatee-dependent, argued just the opposite. They have gone to court to get the manatees removed from the federal endangered list.

“The evidence is overwhelming” that manatees are no longer endangered, said Lisa Moore, a fourth-generation Floridian who’s president of a pro-boating, anti-regulation group called Save Crystal River.

Like what you read? Click here to subscribe.

That people could argue so hotly over such a placid, peaceful animal might seem unlikely. But the fight over the protected status—and thus the future—of the Florida manatee has gone on for 17 years.

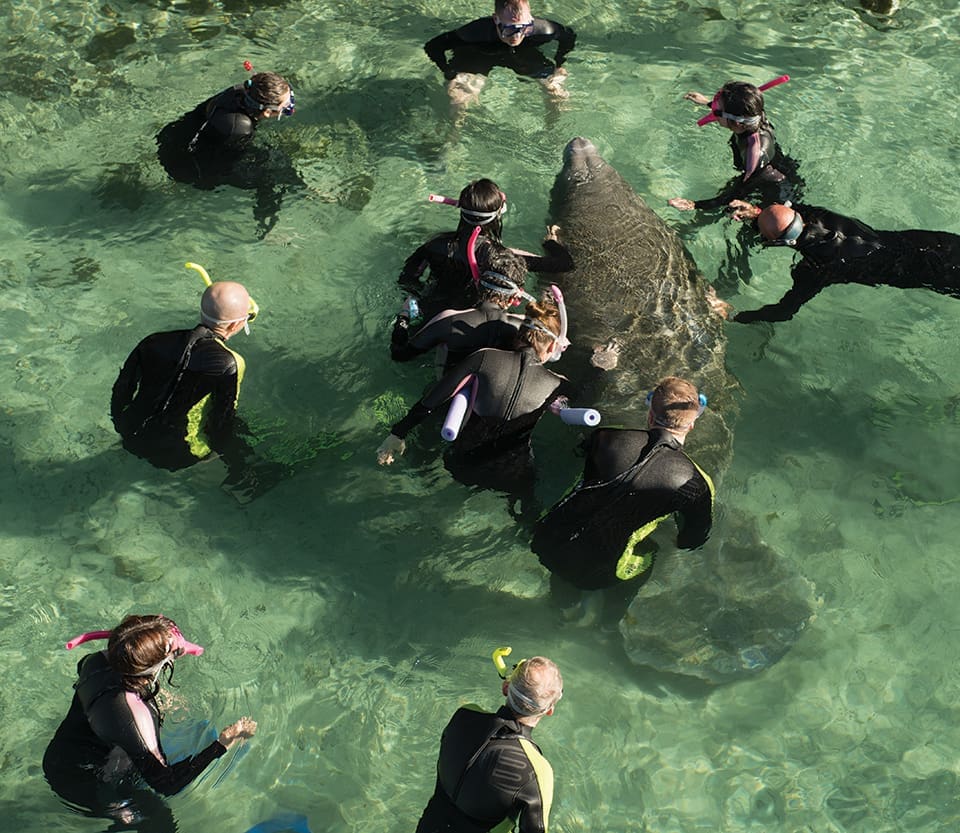

Most endangered species are easy to recognize and difficult to spot. Florida panthers, for instance, despite being the official state animal, hunt at night and thus are seldom seen by humans. Manatees are the endangered species that we Floridians are most likely to encounter. They’re out in the daytime, hanging out by our backyard docks, cruising past where we’re swimming at the beach, or clustering by the hundreds next to a power plant when the weather turns cold. Most of the time, they are solitary creatures, except during cold weather when it’s mating time. That’s when TV stations often report beachgoers seeing seven or eight manatees that appear to be “in distress”—actually, it’s a group of males relentlessly pursuing a lone female. Manatee sex apparently makes for great TV.

Physically, manatees aren’t impressive. Their plump bodies resemble a dumpling with flippers and a fluke. They have shoe-button eyes and whiskers that they brush together in greeting, like a kiss. They swim, eat and poop—helping spread the seeds of seagrass, which provides nursery space for a wide variety of fish species.

FOES AND FRIENDS

Manatees have been swimming in Florida’s waterways for centuries, according to fossils found at our springs and reports from a naturalist in the late 1700s. Early settlers and Native Americans thought manatees were a tasty alternative to venison and beef. As early as the 1880s, some scientists worried that so many manatees had been killed that they might disappear forever. Their solution: Kill some to make taxidermied displays for museums.

Florida passed its first manatee protection law in 1893. Anyone who wanted to kill a manatee had to get a county permit showing that it was for science. The law generally went unenforced. In 1907, a new manatee menace emerged when Ole Evinrude, a Norwegian-American inventor, developed the outboard motor. By the 1940s, people were spotting Florida manatees with propeller scars across their backs. These days, there are so many scarred manatees that scientists use wound patterns to distinguish them as individuals.

When federal biologists first issued an endangered species list, back in 1967, they included manatees on it—but not for the reason most people might expect. The biologists consulted a manatee expert, Craig Phillips, who was the first curator of the Miami Seaquarium.

Phillips warned the federal biologists that there was no way to reliably count manatees. They surface about every five minutes or so to breathe, but spend the rest of their time underwater, making them nearly invisible to humans on the surface. Thus, the size of their population couldn’t be the basis for any decisions about whether they were endangered, he said.

Instead, Phillips suggested they deserved federal protection based on the threats they faced, particularly from speeding boats. The biologists agreed, putting them on the list. At the time, the endangered species law was fairly weak. When Congress passed the far tougher Endangered Species Act in 1973, and it was signed into law by then-President Richard Nixon, manatees were protected—or were supposed to be.

But every year the number of manatees killed by speeding boats increased until finally, in 2000, a coalition of environmental groups, led by Save the Manatee Club, which was founded by Jimmy Buffett and former Senator Bob Graham while Graham was governor, sued both the state and federal governments, contending they were violating the law. The suits also took aim at the loss of habitat to waterfront development, particularly new boating facilities. Both state and federal officials settled the suits, agreeing in 2001 to impose new restrictions on boating speeds and to limit or even ban human access to some areas considered important for manatees.

The settlements, as is usual with civil suits, resulted from backroom negotiations. Boaters and developers raised an outcry, contending they had been left out of discussions crucial to their future (even though the developers and boating industry both were parties to the lawsuits).

In 1999, the year that the environmental groups had originally filed a notice of their intent to sue, a wily boating industry lobbyist named Wade Hopping recommended his clients try a new attack: Get manatees taken off the endangered list.

CONTROVERSY CRYSTALLIZES

All the evidence currently available indicates the manatee population is stable and growing, Hopping wrote in a memo that was reported in the St. Petersburg Times. He most likely based that conclusion on the state’s annual aerial surveys of manatees, in which biologists on a cold winter day fly around and try to count the manatees huddled up in the warm water outfalls of power plants. Robert K. Bonde, a biologist and co-author of The Florida Manatee: Biology and Conservation (University Press of Florida, 2006), has compared the reliability of this method to counting popcorn as it pops.

Hopping’s memo became the blueprint for groups opposed to the new restrictions: get manatees removed from the endangered list or at least knocked down a peg to “threatened.” Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission board members nearly took that step in 2007, but dropped the idea after Buffett himself lobbied then-Governor Charlie Crist backstage at a Tampa concert.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, though, is required by law to review the status of its endangered critters every five years. In 2007 it came out with a review suggesting manatees might no longer fit the endangered definition. It based that ruling on something that wasn’t around when Phillips was advising the federal government: a computer model that predicts the future of the species.

Then the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s move toward dropping the level of protection for manatees stalled. Wildlife officials blamed federal budget cuts for the delay. That didn’t satisfy Lisa Moore’s Save Crystal River group.

Ever since Jacques Cousteau featured the sea cows of St. Johns and Crystal Rivers in a 1972 TV special called “The Forgotten Mermaids,” the town, north of Tampa, has drawn thousands of tourists every year who want to swim with those magical manatees or ride boats out to look at them, especially when they gather in spring-fed Kings Bay during the winter. The city sponsors an annual manatee festival, and the stores sell manatee-themed wine-bottle stoppers, toe rings, shower sponges and cayenne pepper sauce.

But not everyone in Crystal River loves manatees that much after federal officials proposed limiting boat speeds in Kings Bay during the summer as well as the winter to protect the 500+ manatees that now live there year-round. The city council, the county commission and the Citrus County Tea Party raised a ruckus about the proposal.

“We cannot elevate nature above people,” Edna Mattos, leader of the Citrus County Tea Party Patriots, said in a 2011 interview. “That’s against the Bible and the Bill of Rights.”

As a result, Save Crystal River worked with the Pacific Legal Foundation, a libertarian group, to file a suit accusing the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service of dragging its feet on the issue of whether manatees are endangered. The suit got the federal agency

to move.

THE BIG DOWNGRADE

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service took action in January 2016, announcing a proposal that manatees no longer fit the legal definition of endangered. “Endangered” means on the brink of extinction, while “threatened” means facing serious threats but not about to disappear any time soon.

“It’s like taking manatees out of intensive care and putting them in a regular care facility,” U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Jim Valade told reporters at a Miami press conference.

Valade said the agency had calculated there are now more than 6,000 manatees in Florida, far more than in the past 20 years—although no one knows how many there were in 1967, when they were originally put on the endangered species list. Once again, the numbers being used are based on the aerial surveys, and violate Phillips’s counsel about how to think about manatees. The move also stands in contrast to the continued listing of other marine species considered endangered, even though no one knows how many there might be—sharks and sea turtles, for instance.

The federal agency was ready to downgrade the manatees’ protected status, not because the threats of 1967 had been alleviated, but because of a computer forecasted model of the species’ future.

The model, prepared by U.S. Geologic Survey modeler Michael Runge, showed the Florida manatee population had a less than 2.5 percent chance of falling below 4,000 over the next 100 years, “assuming current threats remain constant.”

Critics of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s move, when they got up to speak at the public hearing in the Orlando hotel, complained that that assumption sounded wrong on its face. Manatees’ only predator is man, and the number of humans zooming along Florida’s waterways continues to grow every year. That means, critics said, that “current threats” could not possibly “remain constant.”

The model had other problems. Runge, when interviewed by a reporter, conceded that his model failed to include some important factors. Start with the mass die-offs, known among scientists as “unusual mortality events.”

In 2010, a record number of manatees died: 766, far surpassing the old record of 429, set in 2009. The reason: a long cold snap in January and a second one in December claimed 400 manatee lives. The other 366 most likely died from boating-related deaths and there’s the loss of young manatees that have been orphaned.

In 2013, the record was broken again, as 829 manatees perished. A red tide algal bloom killed more than 200 of them. Meanwhile, between 2012 and 2015, 158 manatees died of a mysterious ailment in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon, once known as the most diverse ecosystem in America. (Pelicans and dolphins died by the score in the polluted lagoon, too.) That die-off sputtered out, then began anew in 2016—no one knows why.

Runge’s model did not take into account either of those events, even though each wiped out a big chunk of the population. But he said he would adjust the model to try to include those “mortality events.”

The larger flaw in the model, though, was another thing it left out: the loss of waterfront habitat, one of the original threats from 1967. Every time a developer turned shoreline into a seawall or converted mangroves into a marina, manatees lost a place to swim, feed and bear their young. There was no way to account for that in the model.

Yet the TV coverage and headlines about the announcement convinced many people that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s move was a done deal, and often, a good one.

ADVOCATES IN ACTION

“People keep coming up to me and saying, ‘Gee, isn’t it great that manatees are no longer endangered?’” says Patrick Rose, the longtime executive director of Save the Manatee Club. “And I have to tell them, ‘That would be great if it were actually true.’”

Rose, an avid boater and diver, is a bearded man with a deliberate way of speaking and a fondness for loud ties. He used to be a federal biologist (on contract)—in fact, he had a position similar to Valade’s, overseeing efforts to defend the manatee. Then Rose went to work for the state, setting up manatee speed zones, before joining Save the Manatee Club.

“I’ve worked my whole professional life for this,” he says with some heat, referring to the change in manatee listing. “I can’t sit by and see them do it for the wrong reasons.”

Rose predicts that, despite assurances by federal officials, the change in status will mean a change in regulations. Already, pro-boating groups are pushing for relaxing the boat-speed rules.

Rose would not rule out filing another lawsuit against the wildlife service if it goes ahead with the change. Such a suit would, in part, be based on comments opposing the agency’s actions by scientists whom the service asked to review its work.

Lynn Lefebvre, Ph.D., who led the U.S. Geological Survey’s Sirenia Project, a team in Gainesville that’s been studying manatees since the 1970s, wrote in an April e-mail to Valade that the manatee deaths in the Indian River Lagoon followed an algal bloom that wiped out 40,000 acres of sea grasses. That was “a catastrophic loss…in the most important manatee habitat on the Atlantic coast, yet it is barely mentioned,” she wrote.

Thomas J. O’Shea, who preceded Lefebvre at the Sirenia Project, agreed in an April statement that the issue of habitat loss and other threats to the manatees remained unaddressed by the proposal: “In my opinion, many of these threats are very likely to continue to increase and are of great concern.” The only supporting reasons the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service gave for saying the threats facing manatees had lessened were “the existence of protective regulations, which in many cases are on paper only and not effective in the field.”

Eleven members of Florida’s congressional delegation have written to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Director Dan Ashe opposing the proposed change, too. Ashe’s agency is expected to make its final decision in 2017.

At the Orlando public hearing, Valade and his colleagues contended that changing the manatees’ status would not alter the regulations that now protect them.

But several speakers said they just do not trust the state or federal governments to hold the protection line once the status has been adjusted.

One speaker suggested that manatees are not the real problem at all.

“The manatee is not the issue; it’s the people,” said Captain Arthur Eikenberg of New Port Richey. “We don’t seem to be able to coexist with anything in nature.”

THEY MIGHT BE GIANTS

Fascinating facts about these flippered creatures

HANGOUTS

Manatees lack gills, so they’re adaptable, able to live in either fresh or salt water. They live wherever they find sea grasses to eat. Find them year round at Homosassa Springs, and at certified manatee rehabilitation spots (Lowry Park Zoo in Tampa, SeaWorld in Orlando and the Miami Seaquarium).

HARDINESS

Snooty, the oldest manatee in captivity, has surpassed age 65. Nobody knows how long manatees can live in the wild, but here’s a clue: Their closest evolutionary relative, elephants, can live to be 86.

HIGHTAILING

When startled, they can zoom along at about 25 mph. Unfortunately, if a boat has rattled them, they can turn to flee in the same direction the vessel’s traveling. Many manatees sport zipper-like scars up their backs from being run over by boats.

HUBBA-HUBBA

Manatees reproduce very slowly, and thus recover from a major die-off slowly. Most manatees have one or two calves at a time. Their sex drive is so strong, though, that when breeding, seven or eight males chase an individual female.