by Katie Hendrick | August 25, 2016

Orange Crush: a Story From the Citrus Groves

The juice on Florida’s citrus-growing history and the a-peel for family farmers, despite facing sticky situations with the iconic crop

Approximately 90 percent of Florida’s oranges are processed into juice. Photography by Jessie Preza

Many beverages conjure the upcoming winter holidays: mulled wine, hot cocoa, peppermint-flavored tea and lattes. But for my family, nothing more aptly toasts the season than an icy, pulpy glass of orange juice, just-squeezed from Hamlins grown on my grandfather’s grove in Zolfo Springs. (It’s great with a splash of champagne, too.)

My family relishes several orange-based treats and traditions, and so does the rest of our state. From vintage postcards that beckoned tourists with depictions of a pastoral wonderland, complete with ruby-lipped beauties plucking fruit, to the standard-issue state license plate, those bright orbs are emblematic of Florida sunshine. Long offered at state welcome centers, orange juice has colored many motorists’ first impressions of Florida. There’s even a state statute that prohibits disparaging comments about our oranges.

“When you say ‘Florida’ to folks up north, they think of three things: beaches, Mickey Mouse and orange trees,” says Ray Royce, 58, a sixth-generation Floridian and former grower, presently an industry lobbyist. “Citrus is a big part of our economy, but an even bigger part of our identity.”

CITRUS EXPRESS

It’s hard to believe oranges aren’t true Florida natives. Originating in China and Southeast Asia, oranges traveled to Europe via Italian traders and on to North America with Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors. Ponce de Leon, historians say, planted the state’s first orange trees around St. Augustine somewhere around 1513; gradually, more and more grew along the St. Johns River, then down through Gainesville and Ocala. Town names such as Orange Lake, Fruit Cove and Citra reflect this fruity development.

Employing nearly 62,000 people, Florida’s citrus industry is valued at approximately $10.8 billion. Photography by Florida Department of Citrus

Florida’s sandy soil and subtropical climate proved ideal for citrus, but the industry didn’t take off on a commercial level until after the Civil War, when improved railroad transportation helped growers ship their product out of state and made it easier for prospective investors to visit groves.

This is when the citrus story gets more personal for me. In the 1870s, my great-great-grandfather, Wade Hampton Harrison, moved from South Carolina to Micanopy, where he started a cattle ranch and planted a few orange trees.

Like what you read? Click here to subscribe.

“That was typical of pioneer families,” says my grandfather, William Harrison Jr., 88, a Sarasota attorney, who has carried on the legacy of raising cattle and growing citrus on a ranch in Hardee County. “They grew a little citrus for personal consumption and to share with friends in town. That was the thing to do.”

Back-to-back freezes in 1894 and 1895 drove most of the state’s ranchers and farmers (occupations that tend to go hand in hand) further south, to cities such as Clermont, Lake Wales and LaBelle. The Harrisons chose Manatee County.

FAMILY FARMERS

In the next generation, my great-granduncle, Wildes Harrison, ran a 3,500-acre cattle ranch in Parrish with a 60-acre grove. “Growing up, on Sundays, the whole family would gather at Uncle Wildes’ place,” my grandfather says. “He grew some tangerines and I could zip them open in a jiffy. I couldn’t wait to raid those trees after church.”

Inspired by his brother, my great-grandfather, William Harrison, a circuit court judge, purchased a 15-acre grove in Palmetto, which his two sons helped tend on weekends and school breaks. Their childhood, during the Great Depression, “involved a lot of pruning and chopping up weeds,” and their diet, a lot of vitamin C, my grandfather says.

William Harrison mows his grove in Zolfo Springs. Photography by Robert Harrison

In February 1959, William Harrison Sr. passed away and my grandfather and his brother inherited the grove, as well as their uncle’s property. They were especially excited about the Parrish grove, for it was “beautiful and very productive,” my grandfather recalls. Sadly, just one year later, Hurricane Donna demolished it.

“I went out the morning after the storm and saw all the fruit on the ground,” my grandfather says. “It was up to my knees.” He estimated that rehabbing the grove would require a hefty financial investment and upwards of 30 hours of physical labor a week. “We were young lawyers with young children. We didn’t have the time or the money to make it work.”

They held on to the Palmetto property for nearly a decade. During those formative years, my mother, aunt and two uncles, all under age 10, developed sweet citrus memories. To entertain his children, my grandfather would peel an orange in one long, curly strip.

“We’d twirl it while singing our ABCs and whatever letter we were on when the orange dropped off was supposed to correspond to our future spouse’s name,” says my aunt, Nancy Taylor, 52. Once the kids “unwound” their oranges, they’d hand them back for my grandfather to cut a hole in the top. “Then we’d throw our heads back and suck the juice out,” she recalls. “There were no straws or napkins involved. We were a sticky, but happy, bunch.”

Rapid development in Palmetto convinced the brothers to sell their grove in the late 1960s. “It wasn’t terribly productive and it was getting crowded out,” my grandfather explains. It would be nearly a quarter century before he revisited his healthy hobby.

GROVE LOVE

As my family was winding down its citrus endeavors, another was just getting started. Joe L. Davis was a self-made man who, in 1940, at age 17, hitchhiked from Wauchula to Tampa to find work. He ran through a string of jobs—stock boy, restaurateur, insurance salesman and car salesman—before he started his “love affair with agricultural real estate” back in his hometown, says his son, Joe Davis Jr. The more he helped clients locate their perfect piece of land, the more enamored Davis became of farming, particularly with oranges, and in 1959, he bought half of a 20-acre grove.

Harrison oversees his grandchildren picking oranges for a Thanksgiving meal (2006). Photography by Robert Harrison

An only child, Davis Jr. cherished time spent with his dad checking on the orange trees. By the time he returned from the University of Florida in 1976 with a law degree, his family had 500 acres of citrus groves. He promptly joined the family business.

“I passed the bar, but deep down, I knew I’d never practice,” he says. “My dad’s business was expanding like crazy. I liked real estate and I loved citrus. I came in when the industry was at its peak, which was really exciting.”

The father-and-son duo worked together for 38 years, until Joe Davis Sr.’s death in 2014 at age 91. During that time, they increased their citrus property by a factor of five, with groves spread among Hardee, DeSoto, Highlands and Polk counties.

STICKY BUSINESS

Looking back, Davis Jr. (who still runs the operations) remembers many years of prosperity accompanied by an abundance of adversity.

“Ask any farmer about the 1980s and they’ll recall it as the decade of the freezes,” he says. During half of those years, temperatures dropped into the 20s, killing millions of trees around the state. “By 1990, citrus production in Florida had been halved. Practically all the groves north of I-4, the corridor from Tampa to Daytona Beach, disappeared.”

Fruit pickers competing in the second annual National Orange Picking Contest in Orlando (1951). Photography by Florida Department of Commerce

Today, the citrus belt covers approximately 515,000 acres and extends from Davie to Winter Haven, with the highest concentration of groves in the landlocked central counties: Hardee, Highlands, Polk and DeSoto. Employing nearly 62,000 people, Florida’s citrus industry is valued at approximately $10.8 billion.

Growers who survived the freezes contended with three major storms in quick succession in 2004. Hurricanes Charley, Frances and Jeanne ripped fruit and leaves off branches, uprooted trees and flooded groves, decreasing the state’s citrus production from 291 to 169 million boxes. It took a costly three years to recover, which was made all the more difficult by canker (a disease often spread by rain, wind or insects) and another hurricane, Wilma, in 2005.

Other challenges of the twentieth century included droughts, low prices, viruses and fruit flies. Now the industry faces citrus greening, considered by many growers and scientists to be the most catastrophic problem yet. (More on this later.)

“We’ve been through it all,” says Barbara Carlton, M.D., a retired physician in Wauchula who, in 1959, married into a seventh-generation cattle and citrus family that owned ranch land in Sumter, and at one time had 700 acres of groves in Hardee and DeSoto counties. She recalls winter nights in the 1960s, before growers used irrigation methods to protect fruit from the cold, when she and her late husband, Albert, had to run around the groves turning on heaters or starting fires. “That was just one of many hardships,” she says. “Agribusiness is not for people looking to get rich quickly. They’d be better off gambling in Las Vegas.”

TREE HUGGERS

About 10 years ago, Carlton noticed troubling signs in her groves. The leaves on trees were turning yellow, and their fruit was unusually small and dropping prematurely. “We had no idea what was going on,” she says. “Today, every grower in the state recognizes those as symptoms of citrus greening.”

Citrus greening is a bacterial disease, spread by the Asian citrus psyllid (a bug), which infects a tree’s phloem (the vascular tissue that transports nutrients), effectively starving it. Researchers at the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences have developed methods to treat greening, but nothing to cure it.

A piece of fruit growing on one of Harrison’s reset trees (2016). Photography by Katie Hendrick

“Greening is like the plant version of AIDS,” says Davis. “We have treatments to keep an infected tree alive, which are expensive, but the tree is left exceptionally weak and susceptible to any kind of stress,” ranging from drought to excessive rainfall to cold temperatures. Many growers, like my grandfather, pull up diseased trees upon detection and replant seedlings. Some have bulldozed their groves, replacing them with crops like strawberries, cucumbers or olives. Others have expanded their cattle business instead.

“Greening affects virtually every citrus grower in the world,” says Royce, executive director of the Highlands County Citrus Growers Association, which represents about 175 growers and 195 businesses connected to the industry. “It’s created tons of problems, but has also made our growers better agronomists.”

Growers who once operated on autopilot now constantly monitor what’s happening in their groves. “They’re educating themselves—both from academic sources and fellow growers,” he says. “They’re very mindful and meticulous with fertilizer treatments these days, basically spoon-feeding the trees nutrients.”

Additionally, Royce has noticed a surge in camaraderie, at the county and state level. “Growers aren’t competing with each other,” he says. “They value dialogue and are working together to solve the greening problem.” Neighbors have begun coordinating their pesticide applications to improve the odds of controlling the bugs that spread greening from grove to grove.

PASSION FRUIT

In 2001, the Harrison brothers sold the Parrish ranch because shopping centers were encroaching on the property. But my grandfather, then 73, still longed for a country retreat to escape the rigors of his law practice.

When he toured a ranch on Charlie Creek in Zolfo Springs later that year, he was simultaneously smitten with and wary of the 110-acre grove it featured. “I could tell it was a good grove that produced a lot of fruit,” he says. “But my first thought was, ‘Whoa, I’m not prepared to get back into the citrus business.’” Then the owners said they had competent maintenance people to oversee day-to-day operations, and he was hooked.

Unlike previous family groves, this one is not just for enjoyment—though my relatives and I devour plenty of oranges, as does my grandfather’s toy poodle and even his cattle. If we can resist eating them directly from the trees, we juice them or pull the cells apart and make ambrosia with banana slices, cherries and coconut flakes. The bulk of his fruit, however, goes to a citrus cooperative that sells to a big beverage conglomerate.

For 15 years, my grandfather has put in three full days a week at the office in Sarasota, leaving—usually before sunrise—each Thursday for a 60-mile drive to the ranch, where he spends the weekend. The quietness, fresh air, wildlife and scent of orange blossoms help him hit the reset button.

“My citrus hobby has been immensely therapeutic,” he says. “I’ve worked out many tricky real estate and tax issues while mowing the grove.”

Echoing Davis, Carlton and Royce, he reiterates that a grove requires substantial attention, even for a “gentleman grower” whose livelihood does not depend on production. He spends at least two days a week examining his trees and conferring with his grove manager. He also regularly reads trade magazines and communicates with other growers to stay on top of industry issues.

“There are many things you worry about—the weather, disease, prices, and so on,” he says. “But you’ll go crazy if you dwell on what could go wrong.” He focuses on quality-control practices and quickly replacing diseased trees.

He intends to be in the citrus (and legal) business for the rest of his life. “My goal is to keep the grove in the best condition possible to pass on to my four children,” he says. “For generations, my family has had a relationship with the land. This is my heritage.”

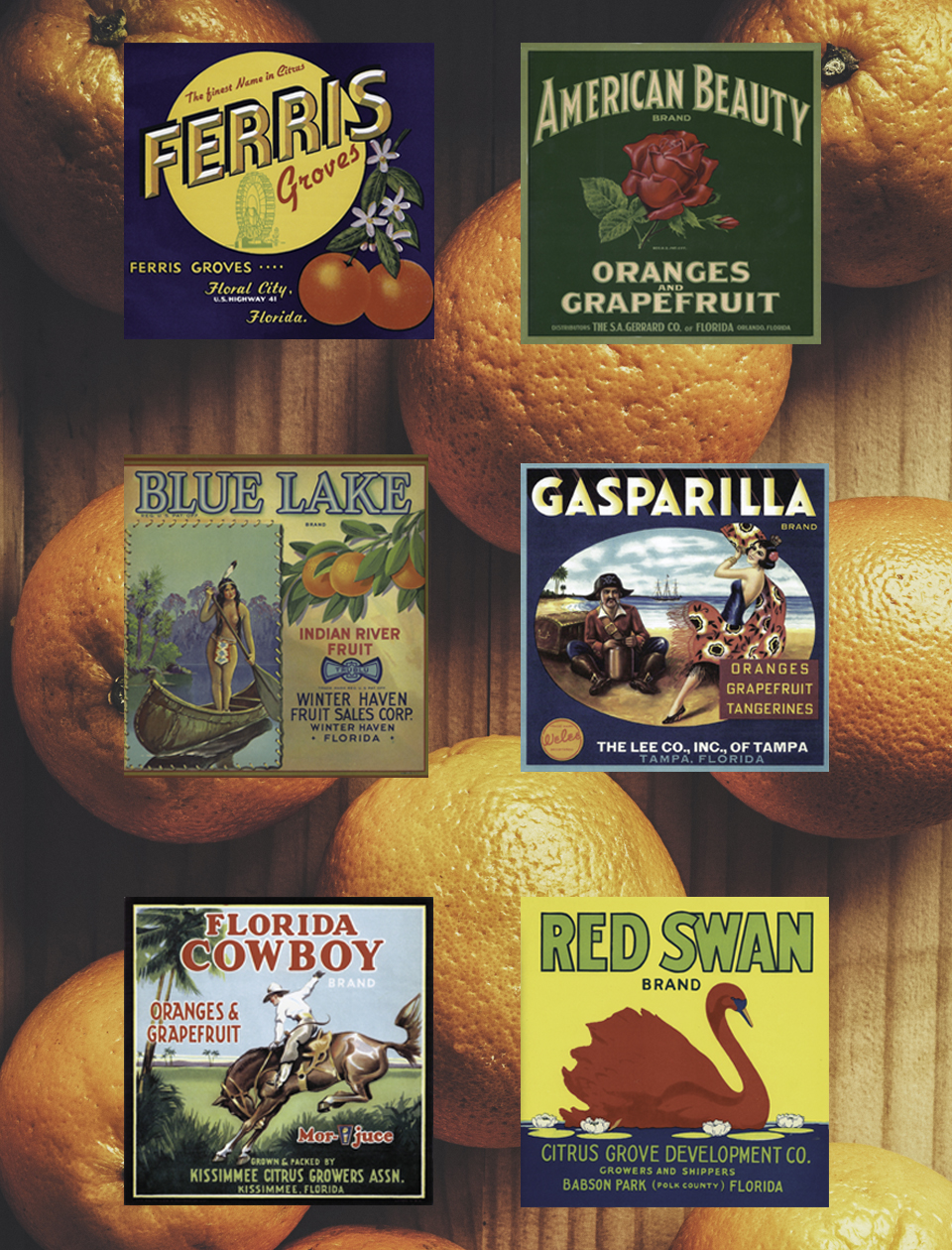

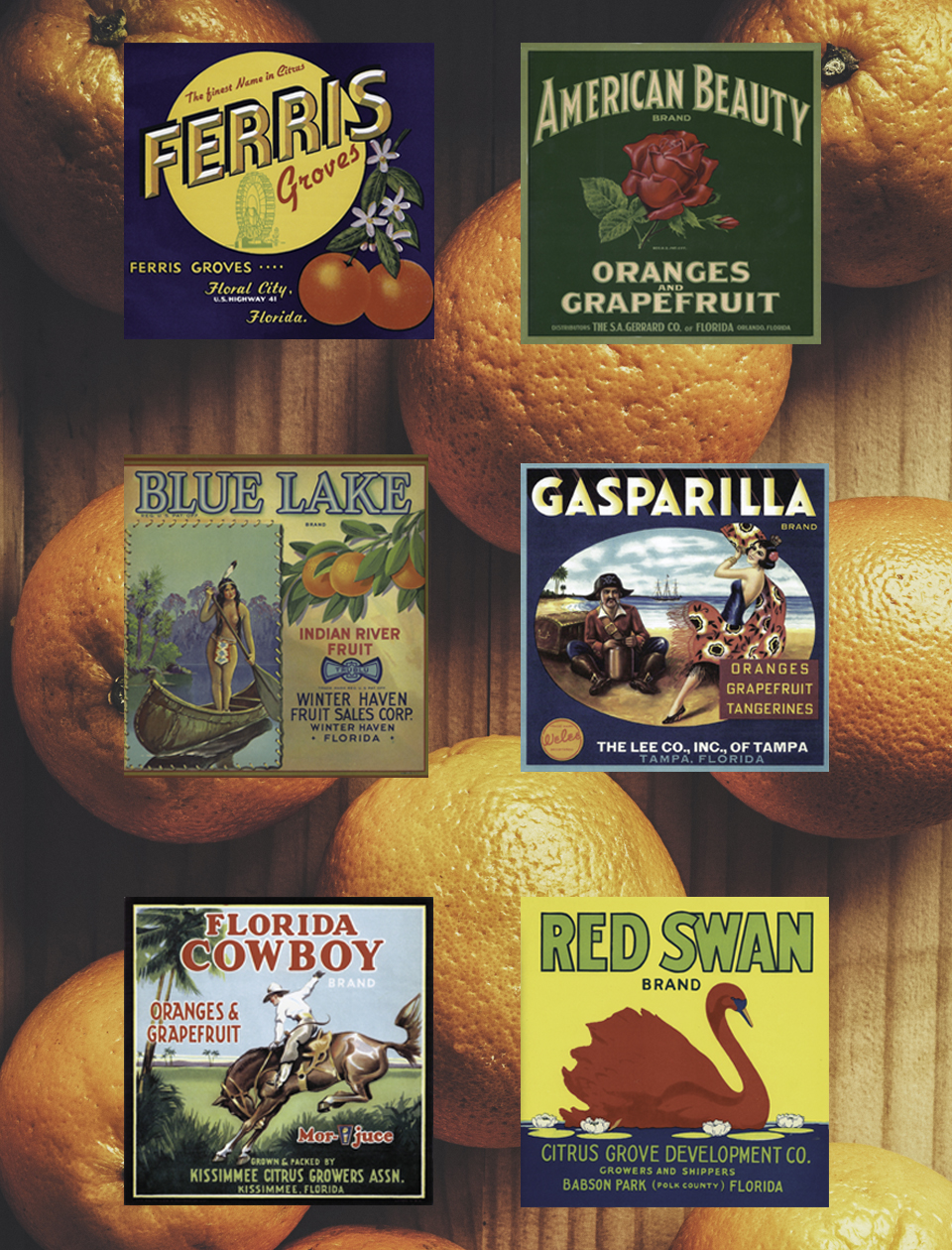

Vintage Orange crate labels; Photography by Katie Hendrick, Deane Briggs, Don Ball

SELLING SUNSHINE

When it came to exporting Florida citrus, crate labels were designed to grab attention. Now, they are highly collectible reminders of a golden era.

After the Civil War, Florida growers began shipping their citrus in crates by railway to fruit auctions in northern markets. To wow buyers, growers needed a way to stand out. Enter bright, eye-catching crate labels.

Popular motifs included flowers, animals, sports themes and Native Americans. Others simply used the company name in an alluring font with an illustration of the fruit. Mindful of Jewish buyers in New York, some growers wrote their names in Hebrew, says Deane Briggs, former treasurer of the Dundee Citrus Growers Association, who has collected vintage Florida citrus labels for more than 20 years.

At first, growers painted designs on crates with a stencil. In the 1920s, lithography rose in popularity, and printed labels were glued to crates. World War II created a wood shortage, so fruit was shipped in cardboard boxes. “By the 1950s, preprinted cardboard boxes became the standard, thus ending the production of citrus labels,” Briggs says.

Available on auction sites such as eBay, labels run from about $1 to more than $200, depending on their rarity. Briggs and a handful of other collectors participate in a sale hosted by Florida’s Natural Growers in Lake Wales (fall) and in Winter Garden (spring).