by Jamie Rich | August 24, 2016

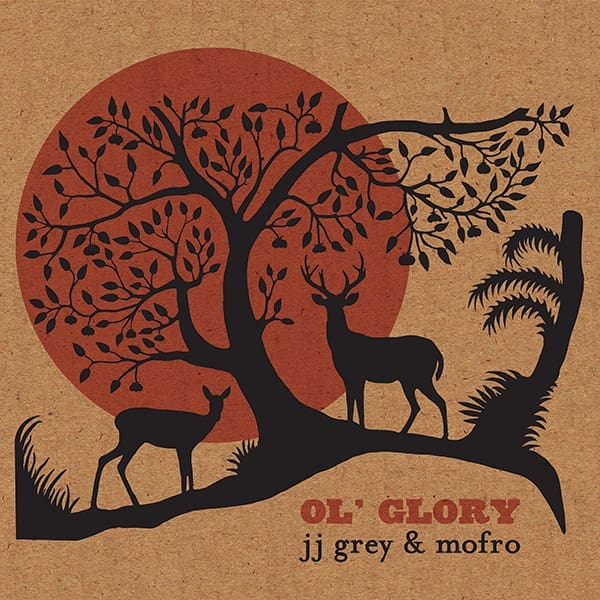

Red, White and JJ GREY

Going deep with JJ Grey, the free-spirited, soul-stirring rocker, on the moments that changed his career, the home place that inspires his lyrics, and discovering new meaning in old songs.

The Floridian with talent as wild as the state from which he hails grew up the son of a police officer and a homemaker in the rural town of Whitehouse, 10 minutes from his grandparents’ poultry farm, in Northeast Florida. With the thundering force of a freight train and the quiet power of a poet, the humble artist celebrates the land, culture and people of his home state like few before him. The band, known as JJ Grey & Mofro, plays its signature funk-blues-swamp-rock sound to packed houses, from St. Augustine to Denver to London, delivering raucous performances and lyrical storytelling. With salt-and-pepper hair and a harmonica slung around his neck, the 48-year-old Grey belts out biographical anthems, taking issue with land developers, honoring his grandparents, mourning the loss of a friend and just stirring up a good time.

Flamingo recently shared a basket of boiled shrimp and chowder with Grey at his favorite neighborhood dive, Chowder Ted’s, near his home on Amelia Island. And while the waitress filled his glass with iced tea on that scorching summer day, he was brimming with stories about which songs still make him cry, his chicken coop and his quest to “build a better me.”

So many people have tried to describe your music—how would you explain it?

JJ: It’s impossible for me to describe it, not because it defies description. It’s like describing yourself: “Right at six feet. White, sort of.” It’s kind of tough, you know what I mean? You can look in the mirror for 40, 45 years, in the morning when you brush your teeth, and you still don’t know who the hell you’re looking at. So I don’t really know what it sounds like. I know who I wished it sounded like.

who do you wish you “sounded like?”

JJ: Like this stuff (pointing to the restaurant speakers playing Tedeschi Trucks Band). Everything from Marvin Gaye to Wilson Pickett, George Jones to Jerry Reed, AC/DC to Lynyrd Skynyrd, Donny Hathaway to Stevie Wonder, James Brown. I want to sound like all that.

What’s the story behind Mofro?

JJ: A guy at work used to say that to me, “’Sup, Mofro.” It just sounded Southern and didn’t mean anything specific so I was like, “I’ll call what I’m doing Mofro.”

Then my grandmother, one day she’s sitting there, you know, crocheting, looking at the TV, and she just stops and is like, “What the hell is Mofro?” Just like she’d been rolling it around. Then she’s like, “You know that song you’re singing about mine and your granddaddy’s last conversation on Earth? You’re singing about your daddy in another song. You’re singing about your boy Trey dying on OxyContin. Are you ashamed of us?” I’m like, “No, what are you talking about?” She said, “Johnny Cash is just Johnny Cash. Some people, they don’t even sing songs about their own people, and they still got their name. Why don’t you put your name on there? Is it embarrassing?”

I called my manager the next day and said, “I’m putting my name on the music.”

What are you playing on tour now?

JJ: My thing with the set is, however I start—whether it’s quiet or I come out BANG!—I break it down, and then build it back up, and then break it down, and then build it back up, and then break it down, and then build it back up and don’t come back down until an encore. Then I usually play something really subdued as the first song of the encore, like This River or The Sun is Shining Down. I don’t like to play The Sun is Shining Down in the middle of the set.

Why wait to play those songs at the end?

JJ: I always wind up tearing up on that one, and same with This River. There’s a couple of them that get me. And I don’t mind that, I enjoy that.

Even though you’ve played the songs thousands of times?

JJ: So whenever I go up there and sing the song, it’s this minute, this second. That’s all there is. And I just try to let that inspire each moment as it unfolds in front of me. You know, you go on stage for two hours a night and you go into what people call the zone. For a period of time, when I [first] started, I was in the zone once out of every 20 shows maybe, and the rest of them I was thinking all

the time.

What were you thinking about during those shows when you weren’t in the zone?

JJ: Stupid stuff. Like you’d be playing at a festival in front of 10,000 people, and 9,999 of them are totally enamored. But one person’s walking away. And you’re like, “Why are they walking away? Am I not doing enough?”

The point is, the small person in us running its mouth all the time in your head, and won’t shut up, and always trying to make you feel like somebody else’s success is your failure can talk you into anything. It can talk you into never walking onstage again. It can talk people into sticking a loaded gun to their head and pulling the trigger. So eventually you’ve got to learn that it’s not you. That’s the giant illusion. I eventually figured a lot of that out. So when I went onstage, I went onstage with a joy to do it. And then it affected my whole life, just turned into this quest to build a better me.

Was there some moment or event that forced you to change?

JJ: Well, it was a bunch of things. One thing was the car crash on the second leg of the tour in 2001. I was driving home, and a car hit us from behind, spun us out, flipped [us] two or three times. My wife was in intensive care for a month, and wonderful people helped us through that whole thing. Anyway, that moment of being so in my own skin, I didn’t think about it, just filed it away. And then I went back to being me again.

I was staying perpetually sick on the road. I had pneumonia for a year and a half on the road, and I kept singing, and I had to take cortisone shots to get the swelling down in my throat and that just prolonged getting well. I stayed sick, sick, sick. My manager was like, “Hey man, I want you to go see this friend of mine. He’s a doctor. But he’s more than a doctor.” It was in Boulder, I was like, “This is some kind of hippie thing?” And even though I’ve got a lot of friends that are hippies, you know, I was a super-redneck kid back then. This was in like 2008. Anyway, I went in there and he didn’t want to see me at first. I was like, “Look, hoss, I didn’t come to you to fix me. I came to you to find out how I can fix myself.” So that was the beginning of changing for me.

EVERYTHING IS A SONG

How do you write songs?

JJ: The songs write themselves, so I try not to do too much. But I’m in midstream with about seven or eight tunes right now. Rule number one, don’t take any of it too serious. Rule number two, there aren’t no rules. And rule number three, let it happen when it happens.

Why do you tell so many stories about your life and Florida?

JJ: It speaks to me, living here does. I took my daughter surfing just a little while ago, and driving here, looking around going, golly, it’s like living a dream. And most of the dream is because of all that out there. It’s speaking whether we hear it or not. At the same time, so often I didn’t know what any of the songs were about early on.

You know, the song This River? People are like, “That’s about the St. Johns River.” It’s about the real world out there, not the world that men make up. The world that men make up, it comes and it goes. If you lived in Colorado, just sitting and looking at that mountain for five minutes, you feel small and it feels wonderful. That’s my tie to Florida with so much of the songs—it’s about feeling small and loving it.

If you didn’t know when you first wrote the songs, what have they become about now?

JJ: So there was this recurring theme over and over again in the music that I wasn’t purposefully putting there to “wake up.” So when I finally kind of woke up, I looked back on those songs and I felt like a guy who was desperately trying to put together some equation that was going to make everything make sense. You’re there like a scientist working day and night. And it’s killing you because you want to come up with this equation. And then one day you finally come up with it, it finally happens. You have this moment of clarity—wham!—and the equation comes and you write it down and you run into your laboratory and there it is written over and over again on your chalkboard. You’ve been writing this equation down all these years, and you never knew it ’til you knew it.

Is the song Every Minute about finding clarity?

JJ: I was in Jamaica on a Jam Cruise at Ocho Rios, and I was having breakfast with some friends of mine in Galactic. I was mad about something that’s going on in some country halfway around the world that I’ve never been to, and I don’t even really know what’s going on over there other than what I’ve been told. I was sitting there with my ass on my shoulders, as my dad would say, just mad, not mad at nobody I’m with.

And then I realized, wait a minute, I’m in Jamaica in the middle of the winter and it’s warm, it’s beautiful, and what the hell have I got to be mad for? I realized that watching the news was poisoning me. It doesn’t mean there’s not a need for people to be informed at all.

HOME-GROWN

Surfing’s a big part of your life. When did you start?

JJ: Fourteen. I had half of a surfboard, and [some guys] had hit it with a machete and a hammer and poked holes. So I took a rubber car mat and glued it over all those holes and that was my boogie board. I rode that thing out at the jetties. That was me surfing until I could get a surfboard. My parents wouldn’t buy me one. I got a board for 10 bucks, and it was about two steps [up from] the car-matted half a surfboard. It was bad. I got a real surfboard a little bit after that.

So how often are you surfing when you’re home these days?

JJ: Anytime there’s waves, as long as it’s halfway decent. I don’t go as much as I’d like, but I’m also working on stuff

all the time, too, trying to catch up. Fixing the mower. The Dixie Chopper slung a belt, so I got to go out there and fix that.

I got to fix the tractor out there, at the other place, and I’m finishing up the

chicken coop.

You have chickens?

JJ: I got them because we inherited them when we bought the house. They were already there. We got 14 now. But I grew up with chickens, so I love chickens. I grew up with a lot more than that. When I was a kid we had maybe 60,000 a cycle, a fryer cycle.

Where were the 60,000 chickens?

JJ: My grandparents had the chicken houses. They’d bring them as biddies, and then my grandparents raised them up to fryer size. Back then it took about eight weeks. Now it takes four weeks with all the crazy steroids, God knows what. They done moved chicken growing out of America, for the most part. That’s why I won’t eat a chicken unless it’s organic.

When you think back on your childhood, what comes to mind?

JJ: Fishing with my grandfather in Lake Lochloosa and Ocean Pond, which is out near Olustee. And Katie’s Night Limit. I can still hear bands playing there. It was an old juke joint in Baldwin, right behind my grandfather’s house, or trailer [in an] old trailer park he had out there.

You hung out at Katie’s and listened to music?

JJ: No, I couldn’t hang out there. I’d get in trouble because I was a kid. But on Saturdays they’d barbecue and I’d be trying to get bottles, because then you could get a nickel for them. I had a cheap-ass uncle that had an old grocery store there, he’d pay us two and a half cents and he’d pocket two and a half cents. And it’s like, “Why would I do that? The Lil’ Champ [store] right there will give us a straight nickel.” Anyhow, I’d see bands that’d be up there playing the Isley Brothers, that kind of music. Now it’s gone.

What was your dad like?

JJ: My dad was a man’s man as far as I was concerned, and he didn’t cuss in front of us. Every now and again he’d get mad and say “damn” or “shit” or something, you know, busting his hand with a hammer or whatever.

My grandmother told me something I’ll never forget. She was getting on to me about something, and I was just a little kid. She said, “Your dad’s out there right now rebuilding that tractor, and right now he can come in this house and bake a better cake than I can. You got to be like your dad. You got to be able to do everything.” So I’ve tried. I’m still trying.

Do you bake?

JJ: I can’t boil water.

You’ve suggested your family is racially mixed. Is that the case?

JJ: I grew up around people on both sides. I don’t know. My grandmother had an Afro. I asked my dad, and my dad said, “Yeah.”

Seventh grade, I got bussed 30 miles to school every morning to James Weldon Johnson downtown. All my friends did. It was called desegregation. They were taking poor white kids and making them go to poor black schools and poor black kids were going to poor white schools.

And you were one of the poor white kids?

JJ: I learned a valuable lesson. That kids are the same. Pretty much mean. Like baby birds, man. By the end of the school year I had X amount of friends, and I had a couple of, not enemies, but a couple of cats I’d just as soon not run into, you know, bullies or whatever. It was the same way when I went to the all-redneck school. Wasn’t no different. Everybody’s the same. People like to think everything’s different.

That’s how I got hip to a lot of the music, too. Because when I was a kid, brothers was listening to stuff like Time, you know. It was called Morris Day and the Time eventually, but it was just called Time back in the day. Isley Brothers, stuff like that.

FLORIDA SON

What Florida artists were influences on your early career?

JJ: Lynyrd Skynyrd, Gold & Platinum was the first album I ever owned. My sister had a bunch of disco 45s that were killer. KC and the Sunshine Band, the Bee Gees, Main Ingredient, a bunch of stuff like that. My sister bought me Gold & Platinum for Christmas one year. My parents let me keep it. Back then, we used to listen to Casey Kasem’s Top 40 countdown, as long as the songs weren’t too risqué, on the way home from church. If they got risqué, my dad shut it off.

Do you have favorite venues around Florida where you love to see or play shows?

JJ: I love playing Jannus Landing. I like playing the House of Blues in Orlando. I love playing in Fort Myers at, aw, what the hell’s the name of that place? It’s a blues joint, but you play outside on an outdoor festival stage— Buckingham Blues Bar! I’ll tell you another place, too. I like playing Fort East Martello in Key West. You drive right by it on the way into Key West. And in the middle of the museum, in the courtyard inside the fort, they put up a big old festival stage. And they put on a concert. I don’t know if they still do that or not. That was awesome.

So let’s talk football. Seminole or Gator?

JJ: Well, I’m split, right down the middle. But I’m a Florida State Seminole and then the Gators.

The Gators was only an hour from where we grew up. And then my brother went to Florida State in ’79. They were terrible back then. I went to a game. I was a little kid, and I was already a Gator fan. I saw that guy come out with the spear—spear in the ground—and I was like, alright, Seminole fan! Then all my Gator friends made fun of me, to the point where I almost hated the Gators, but then I wasn’t going to let them change that. I just like watching college football. If I had to, I’d probably lean Florida State’s way. But I always lean the underdog’s way, and right now it makes me a little bit more of a Florida Gator fan.

Can you clear the air about Disney?

JJ: Yeah I like it. Even though it’s in a song, people think I don’t like Disney. No, no, no, no, no. But how many more Disney Worlds do we need? One’s enough.

What’s your most memorable performance in Florida?

JJ: Playing with the Jacksonville Symphony was one of the highlights of my life. And I’ve done a lot. I don’t mean that to sound like, I’m great, but I’ve had a lot of wonderful opportunities, is the best way to put it, because it’s the truth. But they had this medley called Mofro and Mo’ Overture. A guy combined a bunch of my songs, the melodies from them, and wrote this piece. To hear a 52-piece outfit playing it, it was great. And then to sing—I did it one or two more times after that.

I remember the first time we did it, one of the vice presidents of Gate Petroleum was up there dancing with his wife, going crazy. I was like, “That guy’s cool, man. That’s why he’s successful—because he’s having fun.” That’s what the world needs.

ROAD HARD

What’s your routine on the road?

JJ: I eat less when I’m on the road, which is great. I always lose a little weight when I’m out there. I just exercise some, stuff like that. I come home, and I eat

too much.

Do you drink alcohol on the road?

JJ: I used to. I quit. It’s easy to drink on the road. People want you to get drunk. People buy shots and send it to the stage. But the fun feeling that you have with whiskey or weed, all those things are cool, but they’re all training wheels. Sooner or later you’ve got to ride the bicycle on your own, man. And I don’t need to get shitfaced to have fun. I never did a bunch anyway. I was too much of a control freak to get too drunk or too wasted on weed. Now, I’m not a control freak, but why do I need that shit?

First thing, smoking pot, good weed, that doesn’t really hurt. You might cough a little bit, but that’s not the same thing as the first time you pull off a cigarette you’re like, “God Almighty, this sucks! How does anybody smoke these sumbitches?” But it’s the same way with booze: “Oh my God, this tastes like panther piss.” But then after a while, you’re like, “This tastes good.” So anything you have to develop a taste for is probably something that you should have in moderation.

Does turning 49 in October scare you?

JJ: I don’t pay attention to age. I don’t really care. I don’t never celebrate my birthday. Not because I’m scared of getting older. I love it. I physically feel the same as I did when I was 20.

Are you spiritual?

JJ: I don’t know. I’m not into religion in terms of rules and regulations. I grew up Christian, but I’m not in anybody’s club. When people talk about spiritual stuff, I think of unicorns and the little hippie shop in Cedar Key, you know what I mean? I don’t know anything about that kind of New Age stuff. There’s wisdom in Muslim teachings. There’s wisdom in Confucius, Jesus, everybody. I could keep going. I’ve no claim to any of it because I don’t know. I know one thing: not knowing is part of the gig.

COMEDIC TIMING

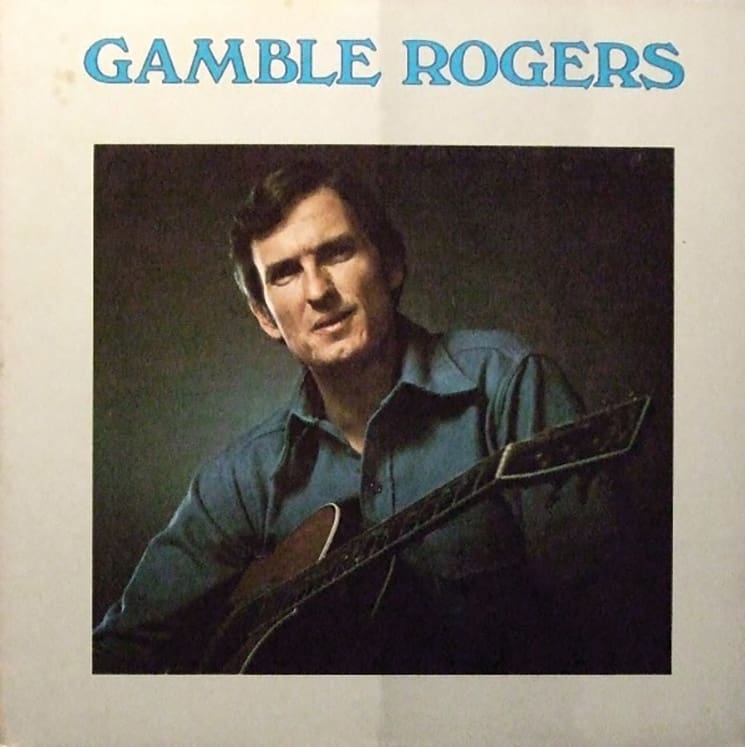

Talented jokesters of the ’50s and ’60s sparked JJ’s love of storytelling.

Brother Dave Gardner was a big influence on me. Brother Dave was a jazz drummer, ordained minister, a beat poet kind of dude from back in the day. And Jerry Clower. Those were two comedians. Jerry Clower, he was a Grand Ole Opry comedian. He didn’t sing, but he had this whole thing about the Ledbetter family from Yazoo City, Mississippi. I used to could recite Live In Picayune from start to finish—I mean, every word—as a kid. In Florida, Gamble Rogers—phenomenal guitarist, great singer, but he was also a storyteller. I know if I’d heard Gamble when I was a kid, it would’ve been the same way. Because, instead of Yazoo City, Mississippi, he had a fictional place called Ocklawaha, Florida, and they had the Purina feed store there and had all these characters, and he’d just tell these hilarious stories. Then he’d break out into a song with the acoustic guitar. He was a master guitar player and just a phenomenal storyteller, I mean just lights-out one of the best.

— JJ Grey

Every Minute

I tried so hard to be the person

everybody thought I was

I pushed myself and everyone

almost over the edge

This mirrored light that sends back

everything that you send out

The grace you give, given back

loving every minute you live

Feels so good to be warm – in the sun

Loving every minute of living

So good to be warm – in the sun

Loving every minute of living

The evil deeds that we do

screaming from the headline

Can’t stop to read, or to watch

’cause I ain’t got the patience or time

To live a life of despair

to live by another man’s word

It’s always been in your hands

to live the life you want while you’re here

Feels so good to be warm – in the sun

Loving every minute of living

So good to be warm – in the sun

Loving every minute of living

I don’t care, what you say to me

Everywhere beauty is all I see

and it don’t make a damn

’cause there ain’t nothing to take from me

I’m loving every minute

I’m loving every minute I’m free

So good to be warm – in the sun

Loving every minute of living

It’s so good to be warm – in the sun

Loving every minute I’m living

Good to be warm – in the sun

Loving every minute I’m living

Good to be warm – in the sun

Loving every minute I’m living

Loving every minute

Loving every minute I’m free

LOCHLOOSA

Homesick but it’s alright

Lochloosa is on my mind

She’s on my mind

I swear it’s ten thousand degrees in the shade

Lord have mercy knows – how much I love it

Every mosquito every rattlesnake

Every cane break – everything

Every alligator every blackwater swamp

Every freshwater spring – everything

All we need is one more damn developer

Tearing her heart out

All we need is one more Mickey Mouse

Another golf course another country club

Another gated community

Lord I need her

Lord I need her

And she’s slipping away

If my grandfather could see her now

He’d lay down and die

Cause every minute every second every hour

Every day – Lord she’s slipping away

Homesick but it’s alright

Lochloosa is on my mind

She’s on my mind

THE ISLAND

So many things you’ve seen

So many stories long forgotten

So many deeds between

Shouting out across the bottom

Beneath a ghostly twilight

Her bosom filled with shining stars

Her secrets sing down through the ages

As bright as lightning bugs in jars

All beneath the canopy

of ageless oaks whose secrets keep

Forever in her beauty

This island is my home

Her rolling hills by hands were built

by natives who were never found

The only hints left of their passing

are ancient shells that ghost the ground

Bone white they tell a story

of all the slaves who graced her shores

of cotton fields so long plowed under

a jungle now upon her stores

All beneath the canopy

of ageless oaks whose secrets keep

Forever in her beauty

This island is my home

All beneath the canopy

of ageless oaks whose secrets keep

Forever in her beauty, ah in her beauty

This island is my home